Problems and Issues Related to Teaching Japanese to Students with Disabilities: Lessons Learned

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal Issue 26 | October 2019

journal Issue 26 | October 2019 Communicating Astronomy with the Public Spotlighting a Black Hole What did it take to create the largest outreach campaign for an astronomical result? Tactile Subaru A project to make telescope technology accessible Naming ExoWorlds Update on the IAU100 NameExoWorlds campaign www.capjournal.org As part of the 100th anniversary commemorations, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) is organising the IAU100 NameExoWorlds global competition to allow any country in the world to give a popular name to a selected exoplanet and its News News host star. The final results of the competion will be announced in Decmeber 2019. Credit: IAU/L. Calçada. Editorial Welcome to the 26th edition of the CAPjournal! To start off, the first part of 2019 brought in a radical new era in astronomy with the first ever image showing a shadow of a black hole. For CAPjournal #26, part of the team who collaborated on the promotion of this image hs written a piece to show what it took to produce one of the largest astronomy outreach campaigns to date. We also highlight two other large outreach campaigns in this edition. The first is a peer-reviewed article about the 2016 solar eclipse in Indonesia from the founder of the astronomy website lagiselatan, Avivah Yamani. Next, an update on NameExoWorlds, the largest IAU100 campaign, as we wait for the announcement of new names for the ExoWorlds in December. Additionally, this issue touches on opportunities for more inclusive astronomy. We bring you a peer-reviewed article about outreach for inclusion by Dr. Kumiko Usuda-Sato and the speech “Diversity Across Astronomy Can Further Our Research” delivered by award-winning astronomy communicator Dr. -

EAST WIND Official Newsletter of the World Blind Union-Asia Pacific No

EAST WIND Official Newsletter of the World Blind Union-Asia Pacific No. 7 Contents of this issue: The Look at Our New President of The World Blind Union The New Board and Policy Council Members of Our Region First Blind Sports Association in Hong Kong Visit to Mongolian Federation of the Blind Reflections on the Commemoration of Bicentenary of Louis Braille’s Birth Historical Workshop in Papua New Guinea 3rd Asia Pacific Disability Forum: General Assembly and Conference Women in Action Sight World: Exhibition in Tokyo Exclusively for Blindness/WBUAP Fundraising Campaign for Cyclone-Hit Myanmar Coming Up From the Editor Contact Details THE LOOK AT OUR NEW THE NEW BOARD AND PRESIDENT OF THE WORLD POLICY COUNCIL IN BLIND UNION: OUR REGION Ms. Maryanne Diamond: the lady the local media in Australia named as PRESIDENT: “Sparkling Diamond” Mr. Chuji Sashida Maryanne is blind and has been all of her life. I became vision-impaired when I was 15 years She has 4 children one who is vision impaired. old. I entered school for the blind. Then I went on She was employed in the information technology to a university and studied law. Currently I am industry for many years before moving into the making researches on employment systems for community sector. She spent four years as the persons with disabilities at the institution set by Executive officer of Blind Citizens Australia, the the Japanese Government. In recent days, I am recognized representative organization of people working on topics such as Convention on the who are blind. three years as the inaugural CEO Rights of Persons with Disabilities, prohibition of of the Australian Federation of Disability disabilities discrimination, employment of Organizations, The peak organization of state and disabilities in each country, and measures for national organizations of people with disability. -

Nemeth Code Uses Some Parts of Textbook Format but Has Some Idiosyncrasies of Its Own

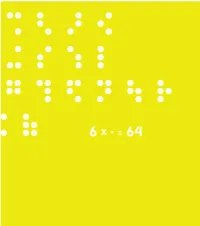

This book is a compilation of research, in “Understanding and Tracing the Problem faced by the Visually Impaired while doing Mathematics” as a Diploma project by Aarti Vashisht at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. 6 DOTS 64 COMBINATIONS A Braille character is formed out of a combination of six dots. Including the blank space, sixty four combinations are possible using one or more of these six dots. CONTENTS Introduction 2 About Braille 32 Mathematics for the Visually Impaired 120 Learning Mathematics 168 C o n c l u s i o n 172 P e o p l e a n d P l a c e s 190 Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION This project tries to understand the nature of the problems that are faced by the visually impaired within the realm of mathematics. It is a summary of my understanding of the problems in this field that may be taken forward to guide those individuals who are concerned about this subject. My education in design has encouraged interest in this field. As a designer I have learnt to be aware of my community and its needs, to detect areas where design can reach out and assist, if not resolve, a problem. Thus began, my search, where I sought to grasp a fuller understanding of the situation by looking at the various mediums that would help better communication. During the project I realized that more often than not work happened in individual pockets which in turn would lead to regionalization of many ideas and opportunities. Data collection got repetitive, which would delay or sometimes even hinder the process. -

World Braille Usage, Third Edition

World Braille Usage Third Edition Perkins International Council on English Braille National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped Library of Congress UNESCO Washington, D.C. 2013 Published by Perkins 175 North Beacon Street Watertown, MA, 02472, USA International Council on English Braille c/o CNIB 1929 Bayview Avenue Toronto, Ontario Canada M4G 3E8 and National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., USA Copyright © 1954, 1990 by UNESCO. Used by permission 2013. Printed in the United States by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data World braille usage. — Third edition. page cm Includes index. ISBN 978-0-8444-9564-4 1. Braille. 2. Blind—Printing and writing systems. I. Perkins School for the Blind. II. International Council on English Braille. III. Library of Congress. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. HV1669.W67 2013 411--dc23 2013013833 Contents Foreword to the Third Edition .................................................................................................. viii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... x The International Phonetic Alphabet .......................................................................................... xi References ............................................................................................................................ -

DBT and Japanese Braille

AUSTRALIAN BRAILLE AUTHORITY A subcommittee of the Round Table on Information Access for People with Print Disabilities Inc. www.brailleaustralia.org email: [email protected] Japanese braille and UEB Introduction Japanese is widely studied in Australian schools and this document has been written to assist those who are asked to transcribe Japanese into braille in that context. The Japanese braille code has many rules and these have been simplified for the education sector. Japanese braille has a separate code to that of languages based on the Roman alphabet and code switching may be required to distinguish between Japanese and UEB or text in a Roman script. Transcription for higher education or for a native speaker requires a greater knowledge of the rules surrounding the Japanese braille code than that given in this document. Ideally access to both a fluent Japanese reader and someone who understands all the rules for Japanese braille is required. The website for the Braille Authority of Japan is: http://www.braille.jp/en/. I would like to acknowledge the invaluable advice and input of Yuko Kamada from Braille & Large Print Services, NSW Department of Education whilst preparing this document. Kathy Riessen, Editor May 2019 Japanese print Japanese print uses three types of writing. 1. Kana. There are two sets of Kana. Hiragana and Katana, each character representing a syllable or vowel. Generally Hiragana are used for Japanese words and Katakana for words borrowed from other languages. 2. Kanji. Chinese characters—non-phonetic 3. Rōmaji. The Roman alphabet 1 ABA Japanese and UEB May 2019 Japanese braille does not distinguish between Hiragana, Katakana or Kanji. -

Aspects of Deafblindness in Japan

Aspects of deafblindness in Japan By Jacques Souriau Introduction In the extraordinary world of deafblindness, one can feel at home in any place on this planet. Cultures differ, but when it comes to deafblindness, the challenges are the same. In June 2016, I was offered the opportunity to experience the universality of deafblindness in a country where the culture is quite unique: Japan. It is a fact that international collaboration and professional publications are greatly influenced by European and American (private or public) organizations using English as the main language of communication. As a result, too little is known of countries (and there are many) which do not participate as intensively in this network. Therefore, when I got an invitation to take part in a project that would give me the possibility to have a direct contact with deafblind people, family members and professionals in Japan - a country known to me for its sophisticated culture and advanced technology, I said "yes" without hesitation. This invitation came to me from two colleagues: Mrs Megue Nakazawa and Professor Masayuki Sato. Mrs. Megue Nakazawa, once a senior researcher at the National Institute of Special Education in Japan1, she now occupies the position of Principal at the Yokohama Christian School for the Visually Impaired (Kunmoo-Gakuin)2. Her professional activities led her to develop a strong interest in blindness and deafblindness. I had the pleasure to meet her on the occasion of a long study visit in Norway and France during the 1990’s as well as during various DbI conferences. At the Yokohama Christian School for the Visually Impaired (where there are also six deaf individuals, she is one of the successors of Mrs. -

AILO Teaching Materials Brochure 2019

www.adaptcentre.ie/ailo Teaching Materials 2019 Improving Second Level Students’ Problem-Solving Skills Run by Teaching Materials 2019 Improving Second Level Students’ Problem-Solving Skills Contents 1 TEACHING MATERIALS 2019 OVERVIEW 3 2 WHY ARE PROBLEM SOLVING SKILLS IMPORTANT? 5 2.1 AILO and the Curriculum 5 3 AILO 2019 WORKSHOP MATERIALS 6 3.1 Workshop Attendance 7 3.2 Pre-Welcome Survey 8 3.3 Workshop Slides 9 3.4 Introductory Puzzles 11 3.5 Preliminary Round Level Puzzle - “Japanese Braille” 16 3.6 National Final Level Puzzle – “Lalana” 17 3.7 Solutions 18 3.8 Post-Workshop Survey 30 4 AILO MONTHLY SAMPLES PUZZLES AND CAREER PROFILES 31 4.1 AILO Sample Set and ADAPT Career Profile One 31 4.2 AILO Sample Set and ADAPT Career Profile Two 40 4.3 AILO Sample Set and ADAPT Career Profile Three 51 2 Teaching Materials 2019 1 TEACHING MATERIALS 2019 OVERVIEW Improving Second Level Students’ Problem-Solving Skills This pack contains the AILO 2019 Teaching Materials which consist of: • The 2018/9 AILO Problem-Solving Workshop Pack • The monthly Sample Puzzle Downloads • Relevant ADAPT Researcher Career Profiles The ADAPT AILO Problem-Solving workshop materials were developed and tested in Summer 2018 thanks to funding from Science Foundation Ireland and the Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. ABOUT AILO The All Ireland Linguistics Olympiad (AILO), run by the ADAPT Research Centre, is the problem solvers’ challenge. The national contest sees secondary school students develop their own strategies for solving complex problems in unfamiliar languages from around the globe. -

Eight-Dot Braille

Eight-dot Braille By Judy Dixon A Position Statement of the Braille Authority of North America Adopted September 2007 BANA's Position There are numerous examples, both historic and modern, in which the six dots of the traditional braille cell have proven inadequate for a particular task. Enterprising inventors, teachers, and braille users have sought to expand the possibilities of the braille cell by increasing the number of dots from six to eight. These expansions have resulted in a cell that is two dots wide and four dots high. Instead of the 63 possible dot combinations in a six-dot cell, an eight-dot cell yields 255 possible dot combinations. Typically, the dots of the eight-dot braille cell are numbered 1, 2, 3, 7 downward on the left and 4, 5, 6, 8 downward on the right. BANA recognizes that eight-dot braille systems have proven to be extremely useful, particularly in the technical areas such as mathematics and the sciences. While BANA currently has no official codes that incorporate eight dots, BANA plans to closely monitor all developments in the area of code extensions involving additional dots and will continue to assess their utility through its technical committees. This paper will provide an overview of eight-dot braille, its historic uses and modern developments. Historic Uses of Eight-dot Braille As the use of braille evolved throughout the world, there have been at least three instances where an eight-dot "braille" cell has been used for a special purpose. In each of these cases, several eight-dot braille slates were developed to enable users of the special code to write the eight-dot code in addition to reading it. -

Working for Equality: Activism and Advocacy by Blind

WORKING FOR EQUALITY: ACTIVISM AND ADVOCACY BY BLIND INTELLECTUALS IN JAPAN, 1912-1995 By Chikako Mochizuki Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Eric C. Rath ________________________________ Co-Chair William M. Tsutsui ________________________________ J. Megan Greene ________________________________ Michael Baskett ________________________________ Jean Ann Summers Date Defended: September 4, 2013 ii The Dissertation Committee for Chikako Mochizuki certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: WORKING FOR EQUALITY: ACTIVISM AND ADVOCACY BY BLIND INTELLECTUALS IN JAPAN, 1912-1995 ________________________________ Chairperson Eric C. Rath ________________________________ Co-Chair William M. Tsutsui Date approved: September 4, 2013 iii Abstract This dissertation examines advocacy by blind activists as the primary catalysts in fighting for equal access to education and employment for blind people in Japan from 1912-1995. Highlighting profiles of prominent blind activists, the chapters describe how they used successful Western models of education and legal rights for the blind to fight for reforms in Japan. Chapter 1 explains how the influence of Christianity and the invention of Japanese braille by Ishikawa Kuraji led blind activists to examine and adapt these western models to Japan. Chapter 2 describes Iwahashi Takeo’s advocacy for greater access to education and employment and the founding of the Nippon Lighthouse Welfare Center for the Blind in 1922. He invited Helen Keller to Japan in 1937 to help promote the importance to society of active participation by blind people. The third chapter examines the career of Honma Kazuo who founded the National Library for the Blind in 1940. -

1 an Analysis of Thai Braille System

µ¦ª ·Á¦µ³®r¦³´ª°´¬¦Á¦¨¨rÅ¥ 1 ª¸¦´¥ °Îµ¡¦Å¡¼¨¥r ¨³ª ·Ã¦r °¦»¤µ³»¨ ³°´¬¦«µ¦r »¯µ¨¦r¤®µª·¥µ¨´¥ ´¥ n° °´¬¦Á¦¨¨r ÁȦ³´ªÁ ¸¥¸ÉÄoºÉ°µ¦Ä¨»n¤µ° ¦³°oª¥Á¨¨rnµÇ Á¦¸¥n°´Ã¥ ¸ÉÂn¨³Á¨¨r¤¸»¼Å¤nÁ· 6 » µ¦¦µ °»Äε®nnµ´³Äo°´ ¦³nµ´ ÁºÉ°µ °´¬¦Á¦¨¨rÄ£µ¬µ°ºÉÃ¥Á¡µ³£µ¬µ°´§¬Åo¤¸¼oª·Á¦µ³®rŪo¨oª°¥nµÁȦ³ Ân¥´Å¤n¤¸µ¦ª·Á¦µ³®r ¦³°´¬¦Á¦¨¨rÅ¥ µª·´¥¸Ê¹¤»n¸É³ª·Á¦µ³®r¦³´ª°´¬¦Á¦¨¨rÅ¥ ¹Éµªnµ³Åo¦´°··¡¨µ °´¬¦Á¦¨¨r°´§¬Â¨³°´¬¦Á¦¨¨r¸É»n ¨µ¦ª·´¥ÂÄ®oÁ®Èªnµ ¦³ÄÁ¦¨¨rť¨³Á¦¨¨r¸É»¤¸¦¼n Á®¤º°´Â¨³¤¸Á¸¥Ä¨oÁ¸¥´ 5 ¦¼ Ä ³¸ÉÁ¦¨¨rť¨³Á¦¨¨r°´§¬¤¸¡¥´³¸É¤¸¦¼Á®¤º°´Â¨³ ¤¸Á¸¥¨oµ¥¨¹´ 15 ¦¼ ¦¼Á¦¨¨rÁ®¨nµ¸Ê´ÁȦ¼Á¦¨¨rÅ¥¡ºÊµ¹Éµ¤µ¦ÎµÅ ¥µ¥ÁÈ°´¬¦ Á¦¨¨rÅ¥Á¡·É¤Á·¤ Ã¥µ¦¦´Á¨¸É¥»Á¦¨¨r£µ¥ÄÁ¨¨r ®¦º°µ¦Á¡·É¤Á¨¨r¸É¤¸¦¼Âµ¥´ª®oµ®¦º° ®¨´´ª°´¬¦µ °´¬¦Á¦¨¨rnªÄ®n¼Îµ® ¹Ê¤µÂ°´¬¦Å¥Â®¹Én°®¹É ¦¸¦³®¹ÉÁ¸¥ ÂnÁ ¸¥ÁȦ¼´o°Ã¥Äo¤µªnµ®¹É´ª°´¬¦È³¼Âoª¥Á¦¨¨r®¹É´ªÁn´ nª°´ ¦ª·¸Ä Á¦¨¨rÅ¥ ¡ªnµ¥¹µ¤µ¦¦³¤°´¬¦Å¥ ¥Áªo¦¸¦¼¦³´o°¸É³Á ¸¥ÁÈÁ¦¨¨r´ªÁ¸¥ª®¨´ ¡¥´³o µ¦°nµ°°Á¸¥ª¦¦¥»r¥´¥¹®¨´Å¦¥µr£µ¬µÅ¥ εε´ Á¦¨¨rÅ¥ ¦³Á¦¨¨r ¡¥´³Á¦¨¨r An Analysis of Thai Braille System Weerachai Umpornpaiboon and Wirote Aroonmanakun Faculty of Arts, Chulalongkorn University Abstract Braille is the writing system used among people with visual impairment. -

Japanese Braille

Japanese Braille J. Marshall Unger University of Hawaii Braille is perhaps the only area of Japanese linguistic life in which serious attention was paid to the problem of word and phrase delimiters before the advent of computers. Japanese orthography does not use spaces in the Western manner, but braille texts must if they are to be intelligible. The first part of this paper describes the fundamentals of Japanese braille, and outlines the spacing rules now in general use. Unlike English braille-in which cells correspond to letters of the alphabet, puctuation marks, or special contracted forms-Japanese braille cells are associated with elements of the syllabic script called kana. This leaves no room for contractions, although it does result in some savings in space . Are these savings superior to what could be achieved in a roman-based Japanese braille system? The second part of this paper answers that question in the negative. This paper has two purposes: to provide a brief description of the Japanese braille writing system (tenji); and to point out the relevance of Japanese braille for the computer treatment of the Japanese language. In particular, braille is one of the very few areas of Japanese linguistic life in which the problem of word spacing (wakachigaki) has received serious attention. Also, the Japanese approach to braille transcription raises some interesting questions about the compressibi I ity of Japanese texts. Krebs (1974:1) defines braille succinctly as "a system of touch reading for the blind which utilizes a cell of 6 dots, three high and two wide, from which 63 different characters can be formed by placing one or more dots in specific positions or combinations within the cell. -

ED312894.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 312 894 FL 018 222 AUTHOR Meadow, Anthoiv, Ed. TITLE Newsletter for .sian and Middle Eastern Languages on Computer, VolumE 1, Numbers 1 and 2. PUB DATE 85 NOTE 70p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Newsletter for Asian and Middle Eastern Languages on Computer; vi n1-2 Jan-Sep 1985 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Alphabets; *Computers; *Computer Software; DiacrAtical Marking; Japanese; Uncommonly Taught Languages; *Word Processing IDENTIFIERS Middle East; South Asian Languages; Transliteration ABSTRACT Numbers 1 and 2 of the first volume of the newsletter contains an editor's page and the following articles: "Diacritics on Wordstar: South Asian Language Transliteration without Customized Software" by Tony Stewart; "The Universal Typewriter" by David K. Wyatt and Douglas S. Wyatt; "Multi-Lingual Word-Processing Systems: Desirable Features from a Linguist's Point of View" by Lloyd Anderson; "A Note on the Production of Macrons in Transliterated Japanese" by Jay Rubin; and "Indian Fonts on the Macintosh" by George Hart. ()the: regular newsletter features include organization news; reviews of books, journals, articles, and products; a calendar of events; and announcemes and inquiries. (MSE) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that an be made * from the original document. ********************************************************************* U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement