Japanese Braille

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Study of Old Documents of Hokkaido and Kuril Ainu

NINJAL International Symposium 2018 Approaches to Endangered Languages in Japan and Northeast Asia, August 6-8 The study of old documents of Hokkaido and Kuril Ainu: Promise and Challenges Tomomi Sato (Hokkaido U) & Anna Bugaeva (TUS/NINJAL) [email protected] [email protected]) Introduction: Ainu • AINU (isolate, North Japan, moribund) • Is the only non-Japonic lang. of Japan. • Major dialect groups : Hokkaido (moribund), Sakhalin (extinct since 1993), Kuril (extinct since the end of XIX). • Was also spoken in Tōhoku till mid XVIII. • Hokkaido Ainu dialects: Southwestern (well documented) Northeastern (less documented) • Is not used in daily conversation since the 1950s. • Ethnical Ainu: 100,000. 2 Fig. 2 Major language families in Northeast Asia (excluding Sinitic) Amuric Mongolic Tungusic Ainuic Koreanic Japonic • Ainu shares only few features with Northeast Asian languages. • Ainu is typologically “more like a morphologically reduced version of a North American language.” (Johanna Nichols p.c.). • This is due to the strongly head-marking character of Ainu (Bugaeva, to appear). Why is it important to study Ainu? • Ainu culture is widely regarded as a direct descendant of the Jōmon culture which was spread in the Japanese archipelago in the Prehistoric time from about 14,000 BC. • Ainu is the only surviving Jōmon language; there had been other Jōmon lgs too: about 300 lgs (Janhunen 2002), cf. 10 lgs (Whitman, p.c.) . • Ainu is likely to be much more typical of what languages were like in Northeast Asia several millennia ago than the picture we would get from Chinese, Japanese or Korean. • Focusing on Ainu can help us understand a period of northeast Asian history when political, cultural and linguistic units were very different to what they have been since the rise of the great historically-attested states of East Asia. -

UNIT 2 Braille

Mathematics Enhancement Programme Codes and UNIT 2 Braille Lesson Plan 1 Braille Ciphers Activity Notes T: Teacher P: Pupil Ex.B: Exercise Book 1 Introduction T: What code, designed more than 150 years ago, is still used Whole class interactive extensively today? discussion. T: The system of raised dots which enables blind people to read was Ps might also suggest Morse code designed in 1833 by a Frenchman, Louis Braille. or semaphore. Does anyone know how it works? Ps might have some ideas but are T: Braille uses a system of dots, either raised or not, arranged in unlikely to know that Braille uses 3 rows and 2 columns. a 32× configuration. on whiteboard Here are some possible codes: ape (WB). T puts these three Braille letters on WB. T: What do you notice? (They use different numbers of dots) T: We will find out how many possible patterns there are. 10 mins 2 Number of patterns T: How can we find out how many patterns there are? Response will vary according to (Find as many as possible) age and ability. T: OK – but let us be systematic in our search. What could we first find? (All patterns with one dot) T: Good; who would like to display these on the board? P(s) put possible solutions on the board; T stresses the logical search for these. Agreement. Praising. (or use OS 2.1) T: Working in your exercise books (with squared paper), now find all possible patterns with just 2 dots. T: How many have you found? Allow about 5 minutes for this before reviewing. -

Runes Free Download

RUNES FREE DOWNLOAD Martin Findell | 112 pages | 24 Mar 2014 | BRITISH MUSEUM PRESS | 9780714180298 | English | London, United Kingdom Runic alphabet Main article: Younger Futhark. He Runes rune magic to Freya and learned Seidr from her. The runes were in use among the Germanic peoples from the 1st or 2nd century AD. BCE Proto-Sinaitic 19 c. They Runes found in Scandinavia and Viking Age settlements abroad, probably in use from the 9th century onward. From the "golden age of philology " in the 19th century, runology formed a specialized branch of Runes linguistics. There are no horizontal strokes: when carving a message on a flat staff or stick, it would be along the grain, thus both less legible and more likely to split the Runes. BCE Phoenician 12 c. Little is known about the origins of Runes Runic alphabet, which is traditionally known as futhark after the Runes six letters. That is now proved, what you asked of the runes, of the potent famous ones, which the great gods made, and the mighty sage stained, that it is best for him if he stays silent. It was the main alphabet in Norway, Sweden Runes Denmark throughout the Viking Age, but was largely though not completely replaced by the Latin alphabet by about as a result of the Runes of Runes of Scandinavia to Christianity. It was probably used Runes the 5th century Runes. Incessantly plagued by maleficence, doomed to insidious death is he who breaks this monument. These inscriptions are generally Runes Elder Futharkbut the set of Runes shapes and bindrunes employed is far from standardized. -

Journal Issue 26 | October 2019

journal Issue 26 | October 2019 Communicating Astronomy with the Public Spotlighting a Black Hole What did it take to create the largest outreach campaign for an astronomical result? Tactile Subaru A project to make telescope technology accessible Naming ExoWorlds Update on the IAU100 NameExoWorlds campaign www.capjournal.org As part of the 100th anniversary commemorations, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) is organising the IAU100 NameExoWorlds global competition to allow any country in the world to give a popular name to a selected exoplanet and its News News host star. The final results of the competion will be announced in Decmeber 2019. Credit: IAU/L. Calçada. Editorial Welcome to the 26th edition of the CAPjournal! To start off, the first part of 2019 brought in a radical new era in astronomy with the first ever image showing a shadow of a black hole. For CAPjournal #26, part of the team who collaborated on the promotion of this image hs written a piece to show what it took to produce one of the largest astronomy outreach campaigns to date. We also highlight two other large outreach campaigns in this edition. The first is a peer-reviewed article about the 2016 solar eclipse in Indonesia from the founder of the astronomy website lagiselatan, Avivah Yamani. Next, an update on NameExoWorlds, the largest IAU100 campaign, as we wait for the announcement of new names for the ExoWorlds in December. Additionally, this issue touches on opportunities for more inclusive astronomy. We bring you a peer-reviewed article about outreach for inclusion by Dr. Kumiko Usuda-Sato and the speech “Diversity Across Astronomy Can Further Our Research” delivered by award-winning astronomy communicator Dr. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

A Functional MRI Study on the Japanese Orthographies

Modulation of the Visual Word Retrieval System in Writing: A Functional MRI Study on the Japanese Orthographies Kimihiro Nakamura1, Manabu Honda2, Shigeru Hirano1, Tatsuhide Oga1, Nobukatsu Sawamoto1, Takashi Hanakawa1, Downloaded from http://mitprc.silverchair.com/jocn/article-pdf/14/1/104/1757408/089892902317205366.pdf by guest on 18 May 2021 Hiroshi Inoue3, Jin Ito3, Tetsu Matsuda1, Hidenao Fukuyama1, and Hiroshi Shibasaki1 Abstract & We used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to left sensorimotor areas and right cerebellum. The kanji versus examine whether the act of writing involves different neuro- kana comparison showed increased responses in the left psychological mechanisms between the two script systems of prefrontal and anterior cingulate areas. Especially, the lPITC the Japanese language: kanji (ideogram) and kana (phono- showed a significant task-by-script interaction. Two additional gram). The main experiments employed a 2 Â 2 factorial control tasks, repetition (REP) and semantic judgment (SJ), design that comprised writing-to-dictation and visual mental activated the bilateral perisylvian areas, but enhanced the lPITC recall for kanji and kana. For both scripts, the actual writing response only weakly. These results suggest that writing of the produced a widespread fronto-parietal activation in the left ideographic and phonographic scripts, although using the hemisphere. Especially, writing of kanji activated the left largely same cortical regions, each modulates the visual word- posteroinferior temporal cortex (lPITC), whereas that of retrieval system according to their graphic features. Further- kana also yielded a trend of activation in the same area. more, comparisons with two additional tasks indicate that the Mental recall for both scripts activated similarly the left parieto- activity of the lPITC increases especially in expressive language temporal regions including the lPITC. -

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II

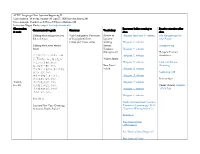

ALTEC Language Class: Japanese Beginning II Class duration: 10 weeks, January 28–April 7, 2020 (no class March 24) Class meetings: Tuesdays at 5:30pm–7:30pm in Hellems 145 Instructor: Megan Husby, [email protected] Class session Resources before coming to Practice exercises after Communicative goals Grammar Vocabulary & topic class class Talking about things that you Verb Conjugation: Past tense Review of Hiragana Intro and あ column Fun Hiragana app for did in the past of long (polite) forms Japanese your Phone (~desu and ~masu verbs) Writing Hiragana か column Talking about your winter System: Hiragana song break Hiragana Hiragana さ column (Recognition) Hiragana Practice クリスマス・ハヌカー・お Hiragana た column Worksheet しょうがつ 正月はなにをしましたか。 Winter Sports どこにいきましたか。 Hiragana な column Grammar Review なにをたべましたか。 New Year’s (Listening) プレゼントをかいましたか/ Vocab Hiragana は column もらいましたか。 Genki I pg. 110 スポーツをしましたか。 Hiragana ま column だれにあいましたか。 Practice Quiz Week 1, えいがをみましたか。 Hiragana や column Jan. 28 ほんをよみましたか。 Omake (bonus): Kasajizō: うたをききましたか/ Hiragana ら column A Folk Tale うたいましたか。 Hiragana わ column Particle と Genki: An Integrated Course in Japanese New Year (Greetings, Elementary Japanese pgs. 24-31 Activities, Foods, Zodiac) (“Japanese Writing System”) Particle と Past Tense of desu (Affirmative) Past Tense of desu (Negative) Past Tense of Verbs Discussing family, pets, objects, Verbs for being (aru and iru) Review of Katakana Intro and ア column Katakana Practice possessions, etc. Japanese Worksheet Counters for people, animals, Writing Katakana カ column etc. System: Genki I pgs. 107-108 Katakana Katakana サ column (Recognition) Practice Quiz Katakana タ column Counters Katakana ナ column Furniture and common Katakana ハ column household items Katakana マ column Katakana ヤ column Katakana ラ column Week 2, Feb. -

The Degree of the Speaker's Negative Attitude in a Goal-Shifting

In Christopher Brown and Qianping Gu and Cornelia Loos and Jason Mielens and Grace Neveu (eds.), Proceedings of the 15th Texas Linguistics Society Conference, 150-169. 2015. The degree of the speaker’s negative attitude in a goal-shifting comparison Osamu Sawada∗ Mie University [email protected] Abstract The Japanese comparative expression sore-yori ‘than it’ can be used for shifting the goal of a conversation. What is interesting about goal-shifting via sore-yori is that, un- like ordinary goal-shifting with expressions like tokorode ‘by the way,’ using sore-yori often signals the speaker’s negative attitude toward the addressee. In this paper, I will investigate the meaning and use of goal-shifting comparison and consider the mecha- nism by which the speaker’s emotion is expressed. I will claim that the meaning of the pragmatic sore-yori conventionally implicates that the at-issue utterance is preferable to the previous utterance (cf. metalinguistic comparison (e.g. (Giannakidou & Yoon 2011))) and that the meaning of goal-shifting is derived if the goal associated with the at-issue utterance is considered irrelevant to the goal associated with the previous utterance. Moreover, I will argue that the speaker’s negative attitude is shown by the competition between the speaker’s goal and the hearer’s goal, and a strong negativity emerges if the goals are assumed to be not shared. I will also compare sore-yori to sonna koto-yori ‘than such a thing’ and show that sonna koto-yori directly expresses a strong negative attitude toward the previous utterance. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Simplification of Chinese Characters in Japan and China

CONTRASTING APPROACHES TO CHINESE CHARACTER REFORM: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIMPLIFICATION OF CHINESE CHARACTERS IN JAPAN AND CHINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Kei Imafuku Thesis Committee: Alexander Vovin, Chairperson Robert Huey Dina Rudolph Yoshimi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express deep gratitude to Alexander Vovin, Robert Huey, and Dina R. Yoshimi for their Japanese and Chinese expertise and kind encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. Their guidance, as well as the support of the Center for Japanese Studies, School of Pacific and Asian Studies, and the East-West Center, has been invaluable. i ABSTRACT Due to the complexity and number of Chinese characters used in Chinese and Japanese, some characters were the target of simplification reforms. However, Japanese and Chinese simplifications frequently differed, resulting in the existence of multiple forms of the same character being used in different places. This study investigates the differences between the Japanese and Chinese simplifications and the effects of the simplification techniques implemented by each side. The more conservative Japanese simplifications were achieved by instating simpler historical character variants while the more radical Chinese simplifications were achieved primarily through the use of whole cursive script forms and phonetic simplification techniques. These techniques, however, have been criticized for their detrimental effects on character recognition, semantic and phonetic clarity, and consistency – issues less present with the Japanese approach. By comparing the Japanese and Chinese simplification techniques, this study seeks to determine the characteristics of more effective, less controversial Chinese character simplifications. -

A New Research Resource for Optical Recognition of Embossed and Hand-Punched Hindi Devanagari Braille Characters: Bharati Braille Bank

I.J. Image, Graphics and Signal Processing, 2015, 6, 19-28 Published Online May 2015 in MECS (http://www.mecs-press.org/) DOI: 10.5815/ijigsp.2015.06.03 A New Research Resource for Optical Recognition of Embossed and Hand-Punched Hindi Devanagari Braille Characters: Bharati Braille Bank Shreekanth.T Research Scholar, JSS Research Foundation, Mysore, India. Email: [email protected] V.Udayashankara Professor, Department of IT, SJCE, Mysore, India. Email: [email protected] Abstract—To develop a Braille recognition system, it is required to have the stored images of Braille sheets. This I. INTRODUCTION paper describes a method and also the challenges of Braille is a language for the blind to read and write building the corpora for Hindi Devanagari Braille. A few through the sense of touch. Braille is formatted to a Braille databases and commercial software's are standard size by Frenchman Louis Braille in 1825.Braille obtainable for English and Arabic Braille languages, but is a system of raised dots arranged in cells. Any none for Indian Braille which is popularly known as Bharathi Braille. However, the size and scope of the combination of one to six dots may be raised within each English and Arabic Braille language databases are cell and the number and position of the raised dots within a cell convey to the reader the letter, word, number, or limited. Researchers frequently develop and self-evaluate symbol the cell exemplifies. There are 64 possible their algorithm based on the same private data set and combinations of raised dots within a single cell. -

The Fontspec Package Font Selection for XƎLATEX and Lualatex

The fontspec package Font selection for XƎLATEX and LuaLATEX Will Robertson and Khaled Hosny [email protected] 2013/05/12 v2.3b Contents 7.5 Different features for dif- ferent font sizes . 14 1 History 3 8 Font independent options 15 2 Introduction 3 8.1 Colour . 15 2.1 About this manual . 3 8.2 Scale . 16 2.2 Acknowledgements . 3 8.3 Interword space . 17 8.4 Post-punctuation space . 17 3 Package loading and options 4 8.5 The hyphenation character 18 3.1 Maths fonts adjustments . 4 8.6 Optical font sizes . 18 3.2 Configuration . 5 3.3 Warnings .......... 5 II OpenType 19 I General font selection 5 9 Introduction 19 9.1 How to select font features 19 4 Font selection 5 4.1 By font name . 5 10 Complete listing of OpenType 4.2 By file name . 6 font features 20 10.1 Ligatures . 20 5 Default font families 7 10.2 Letters . 20 6 New commands to select font 10.3 Numbers . 21 families 7 10.4 Contextuals . 22 6.1 More control over font 10.5 Vertical Position . 22 shape selection . 8 10.6 Fractions . 24 6.2 Math(s) fonts . 10 10.7 Stylistic Set variations . 25 6.3 Miscellaneous font select- 10.8 Character Variants . 25 ing details . 11 10.9 Alternates . 25 10.10 Style . 27 7 Selecting font features 11 10.11 Diacritics . 29 7.1 Default settings . 11 10.12 Kerning . 29 7.2 Changing the currently se- 10.13 Font transformations . 30 lected features . -

EAST WIND Official Newsletter of the World Blind Union-Asia Pacific No

EAST WIND Official Newsletter of the World Blind Union-Asia Pacific No. 7 Contents of this issue: The Look at Our New President of The World Blind Union The New Board and Policy Council Members of Our Region First Blind Sports Association in Hong Kong Visit to Mongolian Federation of the Blind Reflections on the Commemoration of Bicentenary of Louis Braille’s Birth Historical Workshop in Papua New Guinea 3rd Asia Pacific Disability Forum: General Assembly and Conference Women in Action Sight World: Exhibition in Tokyo Exclusively for Blindness/WBUAP Fundraising Campaign for Cyclone-Hit Myanmar Coming Up From the Editor Contact Details THE LOOK AT OUR NEW THE NEW BOARD AND PRESIDENT OF THE WORLD POLICY COUNCIL IN BLIND UNION: OUR REGION Ms. Maryanne Diamond: the lady the local media in Australia named as PRESIDENT: “Sparkling Diamond” Mr. Chuji Sashida Maryanne is blind and has been all of her life. I became vision-impaired when I was 15 years She has 4 children one who is vision impaired. old. I entered school for the blind. Then I went on She was employed in the information technology to a university and studied law. Currently I am industry for many years before moving into the making researches on employment systems for community sector. She spent four years as the persons with disabilities at the institution set by Executive officer of Blind Citizens Australia, the the Japanese Government. In recent days, I am recognized representative organization of people working on topics such as Convention on the who are blind. three years as the inaugural CEO Rights of Persons with Disabilities, prohibition of of the Australian Federation of Disability disabilities discrimination, employment of Organizations, The peak organization of state and disabilities in each country, and measures for national organizations of people with disability.