Suzanne Fischer Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2000 HSS/PSA Program 1

HISTORY OF SCIENCE SOCIETY 2000 ANNUAL MEETING PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE ASSOCIATION 2000 BIANNUAL MEETING 2-5 November 2000 Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Hyatt Regency Vancouver CONTENTS Acknowledgments 3 HSS Officers, Program Chairs, and Council 4 PSA Officers and Program Committee 5 General Information 6 HSS / PSA 2000 Annual Meeting Book Exhibit Layout 7 Floor Plans: Hyatt Regency Vancouver 8-9 Vancouver Points of Interest 10-13 Committees and Interest Groups 14-15 HSS Full Program Schedule 16-20 HSS 2000 Program 21-43 HSS Distinguished Lecture 40 HSS Abstracts 44-187 PSA Full Program Schedule 188-190 PSA 2000 Program 191-202 PSA President’s Address 197 PSA Abstracts 203-245 HSS/PSA Program Index 246-252 Advertisements 253 Cover Illustration: SeaBus riders get the best view of Vancouver from the water. Offering regular service on the busiest routes from 5 a.m. to 2 a.m. and late night owl service on some downtown suburban routes until 4:20 a.m., Greater Vancouver’s transit system--the bus, SkyTrain and SeaBus-- covers more than 1800 square kilometers (695 square miles) of the Lower Mainland. The SkyTrain, a completely automated light rapid transit system, offers direct, efficient service between downtown Vancouver and suburban environs. It follows a scenic elevated 29 kilometer (18 mile) route with 20 stations along the way. All the SkyTrain stations, except Granville, have elevators and each train is wheelchair accessible. The SkyTrain links with buses at most of the 20 stations and connects with the SeaBus in downtown Vancouver. It operates daily, every two to five minutes. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Table of Contents

Vol. 45, No. 1 January 2016 Newsof the lHistoryetter of Science Society Table of Contents From the President: Janet Browne From the President 1 HSS President, 2016-2017 Notes from the Inside 3 Publication of this January 2016 Newsletter provides me in congratulating Angela very warmly on a task Reflections on the Prague a welcome opportunity for the officers of the Society carried out superbly well. Conference “Gendering Science” 4 to wish members a very happy new year, and to thank Lone Star Historians of It is usual at this point in the cycle of Society business our outgoing president Angela Creager most sincerely Science—2015 8 for the incoming president also to write a few forward- for her inspired leadership. Presidents come and go, Lecturing on the History of looking words. As I take up this role it is heartening to but Angela has been special. She brought a unique Science in Unexpected Places: be able to say that I am the eighth female in this position Chronicling One Year on the Road 9 combination of insight, commitment, and sunny good since the Society’s foundation, and the third in a row. A Renaissance in Medieval nature to every meeting of the various committees and The dramatic increase of women in HSS’s structure Medical History 13 phone calls that her position entailed and has been and as speakers and organizers at the annual meeting, Member News 15 an important guide in steering the Society through from the time I first attended a meeting, perhaps a number of structural revisions and essential long- In Memoriam: John Farley 18 reflects a larger recalibration of the field as a whole. -

July, and October

ISSN 0739-4934 NEWSLETTER I {!STORY OF SCIENCE _iu_'i_i_u~-~-~-o~_9_N_u_M_B_E_R_3__________ S00ETY AAASREPORT HSSEXECUTIVE A Larger Role for History of Science COMMITTEE PRESIDENT in Undergraduate Education STEPHEN G. BRUSH, University of Maryland NORRISS S. HETHERINGTON VICE-PRESIDENT Office for the History of Science and Technology, SALLY GREGORY KOHLSTEDT, University of California, Berkeley University of Minnesota EXECU11VESECRETARY HISTORIANS OF SCIENCE have often been called to contribute to under MICHAEL M. SOKAL, Worcester graduate education. As HSS President Stephen G. Brush notes jNewsletter, Polytechnic Institute January 1990, pp. 1, 8-10), historically oriented science courses could be TREASURER come a valuable part of the core curriculum at many institutions, and fac MARY LOUISE GLEASON, New York City ulty at many colleges-especially science professors-have expressed strong EDITDR interest in using materials and perspectives from history of science. RONALD L. NUMBERS, University of We are now called again, this time by the American Association for the Wisconsin-Madison Advancement of Science. The Liberal Art of Science: Agenda for Action, published by the AAAS in May 1990, argues that science is one of the liberal The Newsletter of the History of Science arts and that it should be taught as such, as integrated into the totality of Society is published in January, April, July, and October. Regular issues are sent to individual human experience. This argument and advice may seem obvious to histori members of the Society who reside in North ans of science, but it is a revolutionary departure from tradition for many America. Airmail copies are sent to those scientists, and one that could transform both undergraduate education and members overseas who pay $5 yearly to cover postal costs: The Newsletter is available to the role of our discipline. -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

Neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing—Was Bound And

A DiligentBy Lee A. Witters, M.D. Effort n April 26, 1638—18 years after the One of the giants of Mayflower’s departure for the New World —the 350-ton Diligent of Ipswich set sail 20th-century medicine— from Gravesend, England. Captained by John Mar- Otin, the ship carried 133 passengers. The Diligent made landfall on August 10 in Boston, then pro- neurosurgeon Harvey ceeded immediately to Hingham, Mass., a South Shore town founded just five years earlier. Among the passengers who disembarked and settled there Cushing—was bound and were Matthew Cushing and Henry Smith. What kind of relationship they had with each determined to pay homage other, if any, is not part of recorded history. But the lives of a direct descendant of each—Dr. Harvey Williams Cushing, the father of neurosurgery and a to a seminal American pioneer in endocrinology, and Dr. Nathan Smith, the founder of Dartmouth Medical School—were physician who lived a century destined to connect 300 years later. Both Nathan Improve, Perfect, Smith and Harvey Cushing were giants of Ameri- &P can medicine in their own time, Smith in the ear- before him—Dartmouth erpetuate ly 19th century and Cushing in the early 20th cen- Dr. Nathan Smith tury. Proof of the confluence of their careers lies in Medical School founder and Early American documents in the Dartmouth archives and in a Medical Education bronze plaque that now adorns a hallway in the Remsen Building at Dartmouth Medical School. Nathan Smith. It’s a saga filled At the unveiling of that plaque on June 17, 1929, Harvey Cushing explained that by the 1700s, Oliver S. -

A Complete Bibliography of Publications in Isis, 1990–1999

A Complete Bibliography of Publications in Isis, 1990{1999 Nelson H. F. Beebe University of Utah Department of Mathematics, 110 LCB 155 S 1400 E RM 233 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 USA Tel: +1 801 581 5254 FAX: +1 801 581 4148 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] (Internet) WWW URL: http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/ 25 May 2018 Version 0.07 Title word cross-reference c [1275]. AΠOPHMA [2901]. BOTANIKON [2901]. ΠEPITΩNΠEΠONΘΩNTOΠΩN [1716]. ⊂ [431]. ⊃ [431]. -1708 [2436]. -4 [3189]. /Max [3367, 1215]. 0Die [1766]. 1 [1169, 2655, 2935, 566, 1131, 1939]. 1.7 [1001]. 1.7-7 [1001]. 10 [2649, 2983]. 100 [323]. 129 [1808]. 1333 [1938]. 1336 [2425]. 1345 [2250, 920]. 1400 [3429]. 1420 [2078]. 1450 [1797]. 1483 [348]. 150-Year [2452]. 1500 [29]. 1530 [30]. 1543 [441]. 1550 [2160, 3491, 1246]. 1570 [1998]. 1597 [3531]. 1600 [3326, 2734, 440, 151, 347]. 1610 [1724]. 1610/11 [1651]. 1620 [2652]. 1626 [2003]. 1632 [2000]. 1650 [1377]. 1653 [2901]. 1 2 1654 [2346]. 1657 [732]. 1659 [2816]. 1662 [357]. 1676 [1379, 452]. 1683 [1531]. 1685 [838]. 1687 [1976]. 1690 [2661]. 1696 [1531]. 1699 [835]. 1700 [34, 2491, 3315, 2975]. 1701 [2512]. 1715 [1820]. 1718 [2167]. 1727 [1193, 42]. 1730 [1733]. 1740 [2899]. 1742 [260]. 1750 [3140, 1479, 1560, 3142, 1286, 1566, 2746, 3141, 2351, 1385, 3404]. 1753 [456]. 1770 [460, 3152]. 1773 [3342]. 1777 [1483]. 1783 [2749]. 1785 [3057]. 1789 [461]. 1789/90 [461]. 1791 [3146]. 1792 [1734]. 1795 [2174, 165]. 1799 [561, 3442]. 17de [2814]. 1800 [2356, 326, 2412, 44, 923, 1928, 2902, 2101, 932, 245, 3590]. -

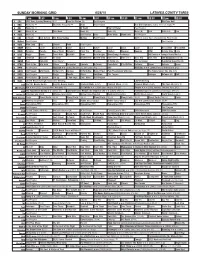

Sunday Morning Grid 6/28/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/28/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Red Bull Signature Series From Las Vegas. Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Paid Vista L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Golf U.S. Senior Open Championship, Final Round. 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 Days to a Younger Heart-Masley 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Bodyguard ›› (R) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Paid Program Al Punto (N) Tras la Verdad República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Madison ›› (2001) Jim Caviezel, Jake Lloyd. -

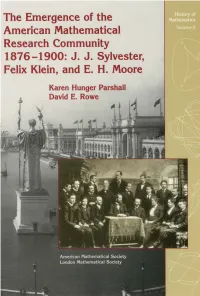

View This Volume's Front and Back Matter

Titles in This Series Volume 8 Kare n Hunger Parshall and David £. Rowe The emergenc e o f th e America n mathematica l researc h community , 1876-1900: J . J. Sylvester, Felix Klein, and E. H. Moore 1994 7 Hen k J. M. Bos Lectures in the history of mathematic s 1993 6 Smilk a Zdravkovska and Peter L. Duren, Editors Golden years of Moscow mathematic s 1993 5 Georg e W. Mackey The scop e an d histor y o f commutativ e an d noncommutativ e harmoni c analysis 1992 4 Charle s W. McArthur Operations analysis in the U.S. Army Eighth Air Force in World War II 1990 3 Pete r L. Duren, editor, et al. A century of mathematics in America, part III 1989 2 Pete r L. Duren, editor, et al. A century of mathematics in America, part II 1989 1 Pete r L. Duren, editor, et al. A century of mathematics in America, part I 1988 This page intentionally left blank https://doi.org/10.1090/hmath/008 History of Mathematics Volume 8 The Emergence o f the American Mathematical Research Community, 1876-1900: J . J. Sylvester, Felix Klein, and E. H. Moor e Karen Hunger Parshall David E. Rowe American Mathematical Societ y London Mathematical Societ y 1991 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 01A55 , 01A72, 01A73; Secondary 01A60 , 01A74, 01A80. Photographs o n th e cove r ar e (clockwis e fro m right ) th e Gottinge n Mathematisch e Ges - selschafft, Feli x Klein, J. J. Sylvester, and E. H. Moore. -

TV Listings FRIDAY, JANUARY 6, 2017

TV listings FRIDAY, JANUARY 6, 2017 17:35 Miraculous Tales Of Ladybug 05:30 Henry Hugglemonster 13:15 Emmerdale And Cat Noir 05:45 Zou 13:45 Coronation Street 18:00 The Next Step 06:00 Art Attack 14:15 Masterpiece With Alan 18:25 Descendants Wicked World 06:30 Henry Hugglemonster Titchmarsh 18:30 Liv And Maddie 06:45 Loopdidoo 15:10 Alphabetical 18:55 Star Darlings 07:00 Zou 16:00 Midsomer Murders 00:20 Wheeler Dealers 07:15 Calimero 17:50 Black Work 19:00 Bunkʼd 06:00 Supa Strikas 01:10 Salvage Hunters 19:25 Disney Mickey Mouse 07:30 Loopdidoo 18:45 Emmerdale 02:00 Marooned With Ed Stafford 00:10 Hank Zipzer 06:25 Supa Strikas 00:35 Binny And The Ghost 19:30 Austin & Ally 07:45 Henry Hugglemonster 19:45 Coronation Street 02:50 Treasure Quest: Snake Island 08:00 Minnieʼs Bow-Toons 06:50 Counterfeit Cat 20:10 Alphabetical 03:40 Fat Nʼ Furious: Rolling Thunder 01:00 Violetta 19:55 Descendants Wicked World 07:00 Star vs The Forces Of Evil 01:45 The Hive 20:00 Backstage 08:05 PJ Masks 21:00 Midsomer Murders 04:30 The Liquidator 08:15 Goldie & Bear 07:15 K.C. Undercover 22:50 Emmerdale 05:00 How Do They Do It? 01:50 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 20:25 Tsum Tsum Shorts 07:40 Atomic Puppet Witch 20:30 Elena Of Avalor 08:30 Jake And The Never Land 05:30 How Do They Do It? Pirates 08:10 Lab Rats 06:00 Blue Collar Backers 02:15 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 20:55 Best Friends Whenever 08:35 Danger Mouse Witch 21:20 Jessie 08:45 Miles From Tomorrow 06:50 Mega Shippers 08:55 Sofia The First 09:00 Lab Rats: On The Edge 07:40 Impossible Engineering 02:40 -

Annals of Medical History Published Quarterly

ANNALS OF MEDICAL HISTORY PUBLISHED QUARTERLY Volume V, No. 4 DECEMBER, 1923 Serial No. 20 EDITOR FRANCIS R. PACKARD, M.D., Philadelphia, Pa. ASSOCIATE EDITORS HORACE MANCHESTER BROWN, M.D. Milwaukee HARVEY CUSHING, M.D.............................................................. Boston CHARLES L. DANA, M.D........................................................ New York * GEORGE DOCK, M.D..................................................................Pasadena FIELDING H. GARRISON, M.D.........................................Washington HENRY BARTON JACOBS, M.D........................................... Baltimore HOWARD A. KELLY, M.D....................................................... Baltimore THOMAS McCRAE^ M.D.......................................................Philadelphia LEWIS STEPHEN PILCHER, M.D......................................... Brooklyn SIR D’ARCY POWER, K.B.E., F.R.C.S. (ENG.) F.S.A. London DAVID RIESMAN, M.D........................................................ Philadelphia JOHN RUHRAH, M.D.................................................................Baltimore CHARLES SINGER, M.D................................................................ Oxford EDWARD C. STREETER, M.D....................................................Boston CASEY A. WOOD, M.D................................................................. Chicago WINTER NUMBER NEW YORK PAUL B. HOEBER, INC., PUBLISHERS 67-69 EAST 59th STREET ANNALS OF MEDICAL HISTORY Volume V, No. 4 DECEMBER, 1923 Serial No. 20 / Original articles are published only -

The Book of Life: Civic Biology in Progressive-Era

THE BOOK OF LIFE CIVIC BIOLOGY IN PROGRESSIVE-ERA NEW YORK CITY Eliza Dexter Cohen April 15, 2015 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Program in Science and Technology Studies at Brown University Thesis Advisor and First Reader: Lukas Rieppel Second Reader: Sohini Ramachandran ABSTRACT Civic Biology was published in 1914 in New York City, becoming the bestselling textbook in the country and the central text of the 1925 Tennessee Scopes Trial, which upheld state laws prohibiting teachers from discussing evolution in their classrooms. Hunter hoped the book, which emphasized systems of order and organization, would provide students with ideals of “civic betterment” by describing the “big underlying biological concepts on which society is built.” This thesis traces resonances between the changing concepts of academic biological research alongside changing pedagogical reforms, immigration legislation, models of political economy, and adolescent psychology, showing how prominent thinkers fused these disparate conversations into an increasingly unified model of society. By looking at textbooks both as they were imagined and as they were actually used in classrooms, this thesis hopes to describe the lived realities within a regime of biopolitics from the point of view of a high school student in Progressive-Era New York City. 3 Table Of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................4 Introduction ....................................................6 The Age