Stone Tool Production صناعة األدوات الحجرية

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Egyptian Predynastic and State Formation

J Archaeol Res DOI 10.1007/s10814-016-9094-7 The Egyptian Predynastic and State Formation Alice Stevenson1 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract When the archaeology of Predynastic Egypt was last appraised in this journal, Savage (2001a, p. 101) expressed optimism that ‘‘a consensus appears to be developing that stresses the gradual development of complex society in Egypt.’’ The picture today is less clear, with new data and alternative theoretical frameworks challenging received wisdom over the pace, direction, and nature of complex social change. Rather than an inexorable march to the beat of the neo-evolutionary drum, primary state formation in Egypt can be seen as a more syncopated phenomenon, characterized by periods of political experimentation and shifting social boundaries. Notably, field projects in Sudan and the Egyptian Delta together with new dating techniques have set older narratives of development into broader frames of refer- ence. In contrast to syntheses that have sought to measure abstract thresholds of complexity, this review of the period between c. 4500 BC and c. 3000 BC tran- scends analytical categories by adopting a practice-based examination of multiple dimensions of social inequality and by considering how the early state may have become a lived reality in Egypt around the end of the fourth millennium BC. Keywords State formation Á Social complexity Á Neo-evolutionary theory Á Practice theory Á Kingship Á Predynastic Egypt Introduction Forty years ago, the sociologist Abrams (1988, p. 63) famously spoke of the difficulty of studying that most ‘‘spurious of sociological objects’’—the modern state. -

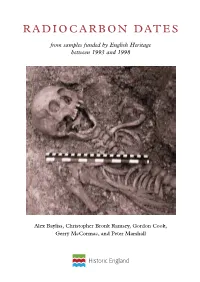

Radiocarbon Dates 1993-1998

RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBON DATES This volume holds a datelist of 1063 radiocarbon determinations carried out between 1993 and 1998 on behalf of the Ancient Monuments Laboratory of English Heritage. It contains supporting information about the samples and the sites producing them, a comprehensive bibliography, and two indexes for reference from samples funded by English Heritage and analysis. An introduction provides discussion of the character and taphonomy between 1993 and 1998 of the dated samples and information about the methods used for the analyses reported and their calibration. The datelist has been collated from information provided by the submitters of the samples and the dating laboratories. Many of the sites and projects from which dates have been obtained are now published, although developments in statistical methodologies for the interpretation of radiocarbon dates since these measurements were made may allow revised chronological models to be constructed on the basis of these dates. The purpose of this volume is to provide easy access to the raw scientific and contextual data which may be used in further research. Alex Bayliss, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Gordon Cook, Gerry McCormac, and Peter Marshall Front cover:Wharram Percy cemetery excavations. (©Wharram Research Project) Back cover:The Scientific Dating Research Team visiting Stonehenge as part of Science, Engineering, and Technology Week,March 1996. Left to right: Stephen Hoper (The Queen’s University, Belfast), Christopher Bronk Ramsey (Oxford -

The Relationship Between the Badarian and the Amratian in Prehistoric Egypt

The Relationship between the Badarian and the Amratian in Prehistoric Egypt Justine J James Two Year Paper Stephen. Harvey Gil Stein March 2004 James 1 Introduction Despite over a century of research since Jacques de Morgan and W. M. F. Petrie made the first discovery and identification of prehistoric artifacts in Egypt, the prehistoric or Predynastic period, especially in the final 2000 or so years leading up to the historic period,1 is not clearly understood. One of the major questions still facing Egyptologists is the question of the origins of pharaonic civilization. Specifically, was pharaonic civilization the product of a gradual evolution of a single cultural antecedent in the Nile valley, the product of a combination of a number of different cultural antecedents in the Nile valley, the product of an entirely new culture whose origins are outside the Nile valley, or a combination of all of the above? Answering this question requires a clearer understanding of prehistoric cultures both in the Nile valley proper and in the surrounding deserts and south into the modern Sudan, especially in terms of chronology and geography. In an attempt to clarify one of these cultural relationships, this paper will focus on the Badarian and Amratian cultural units. The Badarian is traditionally described as a Neolithic farming culture dating to between 5000/4000 and 3900 BC focused in a 35 km strip of around 40 settlement areas in Middle Egypt along the Nile, despite finds of Badarian-like materials outside this presumed homeland at Hierakonpolis, Armant, and Wadi Hammamat.2 The Amratian is described as a Predynastic farming culture with a widespread presence in Upper Egypt spanning Matmar in the north to Wadi Kubbaniya in the south, dating to between 3900 and 3650 BC. -

Estimating the Scale of Stone Axe Production: a Case Study from Onega Lake, Russian Karelia Alexey Tarasov 1 and Sergey Stafeev 2

Estimating the scale of stone axe production: A case study from Onega Lake, Russian Karelia Alexey Tarasov 1 and Sergey Stafeev 2 1. Institute of Linguistics, Literature and History, Pushkinskaya st.11, 185910 Petrozavodsk, Russia, Email: [email protected] 2. Institute of Applied Mathematical Research, Pushkinskaya st.11, 185910 Petrozavodsk, Russia, Email: [email protected] Abstract: The industry of metatuff axes and adzes on the western coast of Onega Lake (Eneolithic period, ca. 3500 – 1500 cal. BC) allows assuming some sort of craft specialization. Excavations of a workshop site Fofanovo XIII, conducted in 2010-2011, provided an extremely large assemblage of artefacts (over 350000 finds from just 30 m2, mostly production debitage). An attempt to estimate the output of production within the excavated area is based on experimental data from a series of replication experiments. Mass-analysis with the aid of image recognition software was used to obtain raw data from flakes from excavations and experiments. Statistical evaluation assures that the experimental results can be used as a basement for calculations. According to the proposed estimation, some 500 – 1000 tools could have been produced here, and this can be qualified as an evidence of “mass-production”. Keywords: Lithic technology; Neolithic; Eneolithic; Karelia; Fennoscandia; stone axe; adze; gouge; craft specialization; mass-analysis; image recognition 1. Introduction 1.1 Chopping tools of the Russian Karelian type; Cultural context and chronological framework This article is devoted to quite a small and narrow question, which belongs to a much wider set of problems associated with an industry of wood-chopping tools of the so-called Russian Karelian (Eastern Karelian) type from the territory of the present-day Republic of Karelia of the Russian Federation. -

Archaeological and Geochemical Investigation of Flint Sources In

Archaeological and geochemical investigation of flint sources in Britain and Ireland By Seosaimhín Áine Bradley A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire MARCH 2017 1 ABSTRACT This study investigates the archaeological use of flint in Britain and Ireland from the Mesolithic to the Bronze Age through geochemical analysis of flint samples obtained from the major areas of chalk geology within these islands (Northern, Southern, Transitional, and Northern Ireland), and provenancing of artefactual assemblages. Recent approaches to provenancing flint have demonstrated that this is indeed possible, however this approach encompasses a larger study area and provides a comparison of two methodologies, one destructive (acid digestion ICP-MS) and one non-destructive (pXRF). Acid digestion ICP-MS and pXRF are capable of detecting a range of elements in a given sample, although they each have specific advantages and disadvantages when applied to archaeological material. There are three main research questions that are addressed in this thesis: ● Determine geochemical composition of flint samples from primary chalk outcrops; ● Assess differences between flint from different chalk provinces; ● Compare acid digestion ICP-MS and pXRF in achieving these objectives. The results indicate that flint from the major areas of chalk geology in Britain and Ireland can be distinguished using the methodologies stated above. There are some difficulties in distinguishing between the Southern and Northern Ireland chalk province flint samples, however the samples from the Northern chalk province are very well differentiated. Archaeological assemblages chosen from throughout the study area and from a wide chronological span were sampled using pXRF and subjected to statistical analysis. -

Before the Pyramids Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu Before the pyramids oi.uchicago.edu before the pyramids baked clay, squat, round-bottomed, ledge rim jar. 12.3 x 14.9 cm. Naqada iiC. oim e26239 (photo by anna ressman) 2 oi.uchicago.edu Before the pyramids the origins of egyptian civilization edited by emily teeter oriental institute museum puBlications 33 the oriental institute of the university of chicago oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Control Number: 2011922920 ISBN-10: 1-885923-82-1 ISBN-13: 978-1-885923-82-0 © 2011 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2011. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago This volume has been published in conjunction with the exhibition Before the Pyramids: The Origins of Egyptian Civilization March 28–December 31, 2011 Oriental Institute Museum Publications 33 Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban Rebecca Cain and Michael Lavoie assisted in the production of this volume. Published by The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 1155 East 58th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 USA oi.uchicago.edu For Tom and Linda Illustration Credits Front cover illustration: Painted vessel (Catalog No. 2). Cover design by Brian Zimerle Catalog Nos. 1–79, 82–129: Photos by Anna Ressman Catalog Nos. 80–81: Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford Printed by M&G Graphics, Chicago, Illinois. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Service — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984 ∞ oi.uchicago.edu book title TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword. Gil J. -

Stone Axe Studies in Ireland

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271899048 Stone Axe Studies in Ireland Article · January 2014 DOI: 10.1017/S0079497X00004242 CITATIONS READS 11 212 3 authors: Alison Sheridan Gabriel Cooney National Museums Scotland University College Dublin 124 PUBLICATIONS 1,411 CITATIONS 44 PUBLICATIONS 294 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Eoin Grogan National University of Ireland, Maynooth 6 PUBLICATIONS 56 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: North Roes Felsite Project View project Scottish archaeology View project All content following this page was uploaded by Alison Sheridan on 02 March 2020. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 58, 1992, pp. 389-416 Stone Axe Studies in Ireland By ALISON SHERIDAN1, GABRIEL COONEY2 and EOIN GROGAN3 This paper starts by outlining the history of stone axe studies in Ireland, from their antiquarian beginnings to 1990. It then offers a critical review of the current state of knowledge concerning the numbers, distribution, findspot contexts, morphology, size, associated finds, dating and raw materials of stone axes. Having proposed an agenda for future research, the paper ends by introducing the Irish Stone Axe Project—the major programme of database creation and petrological identification, funded by the National Heritage Council, currently being undertaken by GC and EG. 'AG 425. Stone axe, 87/i6" X 35/s", found by "Richard Glen- clear, the study of stone axes in Ireland has been far non and James Nolan of the Batchelor's Walk, Dublin, stuck from dormant. -

Vol 138 General Index

GENERAL INDEX Page numbers in italics refer to illustrations Adams, Sophia, 'The contents and context Appledore 235,244 of the Boughton Malherbe Late Bronze arrowhead,flint, Neolithic 275 Hoard' 37-64 Ashbee,Andrew, Zeal Unabated: The Life of JElfstan,Abbot 214-15 Thomas Fletcher Waghorn (1800-1850), JEscingas 4-5 reviewed 319-21 JEthelberht (I), king 4, 13, 14, 19, 78, 201, Ashingdon 3 206, 210, 211 Atkyn, Beatrice,huckster 194 JEthelberhtII 207 axes JEthelburh,Queen 201-19 Neolithic, flint 276 JEthelhun 3 Bronze Age see Boughton Malherbe Albert, co-Duke of Brunswick and Luneburg 5,6, 7, 14 Bachelere, Godelena and Robert 198 n.36 Alcotes, Richard 190,193 Baldwin, Robert, 'Antiquarians, Victorian par Algood,John and Constance,ostclothmaker 192 sons and re-writingthe past: How Lyminge altars, Roman 165, 168, 169 parish church acquired an invented dedicat Arnet,Margaret 188 ion' 201-26 Andrew and Wren, map (1768) 84 Baron, Michael, The Royal Heads Bells of Andrews, Phil et al., Digging at the Gateway. England and Wales,reviewed 316-17 The Archaeology of the East Kent Access barrow mound(?) 137,138, 146 (Phase II),reviewed 309-11 barrows and barrow sites 129-30, 145, 146, Anglo-Saxon/Saxon period 4 206,223 n.25 church dedication and minster, Lyminge Barton, Lester 265, 266 201-26 Basford,Hazel, book review by 316-17 dens 232 beads, Roman glass 89, 100, 272 early Saxon settlement 237 Beck, G.J.D' A (Jimmy) 260-2,267, 277 horses (depiction of) 1-36 Beckley (Sussex) 228 see also Canterbury,Barton Court Grammar Bede 2, 4, 6, 7, 70, 201, 203, -

Variation in Ancient Egyptian Stature and Body Proportions

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by e-Prints Soton AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 121:219–229 (2003) Variation in Ancient Egyptian Stature and Body Proportions Sonia R. Zakrzewski* Department of Archaeology, University of Southampton, Southampton SO17 1BF, UK KEY WORDS stature; limb proportions; social complexity; SES; Egypt ABSTRACT Stature and the pattern of body propor- parity is suggested to be due to greater male response to tions were investigated in a series of six time-successive poor nutrition in the earlier populations, and with the Egyptian populations in order to investigate the biological increasing development of social hierarchy, males were effects on human growth of the development and intensi- being provisioned preferentially over females. Little fication of agriculture, and the formation of state-level change in body shape was found through time, suggesting social organization. Univariate analyses of variance were that all body segments were varying in size in response to performed to assess differences between the sexes and environmental and social conditions. The change found in among various time periods. Significant differences were body plan is suggested to be the result of the later groups found both in stature and in raw long bone length mea- having a more tropical (Nilotic) form than the preceding surements between the early semipastoral population and populations. Am J Phys Anthropol 121:219–229, 2003. the later intensive agricultural population. The size dif- © 2003 Wiley-Liss, Inc. ferences were greater in males than in females. This dis- Within Egypt, the transition from a mainly pasto- retardation of individual childhood growth (Good- ral and nomadic lifestyle to a settled agricultural man et al., 1984; Martin et al., 1984), reduction in subsistence pattern coincided with the development the size and robusticity of the adult population (An- of state-level and hierarchical social organization. -

Repton's Viking Valhalla

ISSUE 16 JANUARY 2019 Archaeology and Conservation in Derbyshire and the Peak District ACID Inside: Meet Dan Snow: The History Guy Elvaston Castle Masterplan Lost Villages of the Derwent Repton’s Viking Valhalla 2019 | ACID 1 Plus: Our year in numbers: planning and heritage statistics Foreword: ACID Archaeology and Conservation in Derbyshire and the Peak District Editor: Roly Smith, Heritage is a living 33 Park Road, Bakewell, Derbyshire DE45 1AX Tel: 01629 812034; email: [email protected] asset For further information (or more copies) please email Natalie Ward at: [email protected] Designed by: Phil Cunningham ikings feature heavily in this year’s edition of ACID. Three separate projects www.creative-magazine-designer.co.uk have revealed more of the Viking presence in Repton, all using new techniques to expand on previous discoveries. The Viking connection continues with a Printed by: Buxton Press www.buxtonpress.com V profile of Dan Snow, who has presented TV programmes about the subject. His new The Committee wishes to thank our sponsors, venture History Hit includes creating podcasts about history. These can particularly Derbyshire County Council and the Peak appeal to the generation who watch TV on demand and choose podcasts over radio District National Park Authority, who enable this publication to be made freely available. programmes. Perhaps we should create an ACID podcast in the future! Derbyshire Archaeology Advisory Committee Other projects have shed light on what we think of as familiar well-studied Buxton Museum and Art Gallery Creswell Crags Heritage Trust landscapes – Chatsworth and the Derwent Valley Mills. -

In Search of the Origins of Lower Egyptian Pottery: a New Approach to Old Data

PREVIOUSLY RELEASED VOLUMES IN SERIES „STUDIES IN AFRICAN ARCHAEOLOGY” SAA vol. 1. Lech Krzyżaniak and Michał Kobusiewicz (eds.), Origin and Early Development of Food-Producing Cultures in North-Eastern Africa. Poznań 1984. 16 vol. 2. Lech Krzyżaniak and Michał Kobusiewicz (eds.), Late Prehistory of the Nile Basin In Search of the Origins and the Sahara. Poznań 1989. A New Approach to Old Data to Approach A New Pottery: Egyptian In of Lower of the Origins Search vol. 3. Lech Krzyżaniak, Late Prehistory of the Central Sudan (in Polish, with English of Lower Egyptian summary). Poznań 1992. vol. 4. Lech Krzyżaniak, Michał Kobusiewicz and John Alexander (eds.), Environmental Change and Human Culture in the Nile Basin and Northern Africa until the Second Pottery: Millenium BC. Poznań 1993. A New Approach to Old Data vol. 5. Lech Krzyżaniak, Karla Kroeper and Michał Kobusiewicz (eds.), Interregional Contacts in the Later Prehistory of Northeastern Africa. Poznań 1996. vol. 6. Marek Chłodnicki, Pottery in the Neolithic Societies of the Central Sudan (in preparation). vol. 7. Lech Krzyżaniak, Karla Kroeper and Michał Kobusiewicz (eds.), Recent Research into Agnieszka Mączyńska the Stone Age of Northeastern Africa. Poznań 2000. vol. 8. Lech Krzyżaniak, Karla Kroeper and Michał Kobusiewicz (eds.), Cultural Markers in the Later Prehistory of Northeastern Africa and Recent Research. Poznań 2003. vol. 9. Karla Kroeper, Marek Chłodnicki and Michał Kobusiewicz (eds.), Archaeology of the Earliest Northeastern Africa. In Memory of Lech Krzyżaniak. Poznań 2006. vol. 10. Marek Chłodnicki, Michał Kobusiewicz and Karla Kroeper (eds.), Kadero: the Lech Krzyżaniak excavations in the Sudan. Poznań 2011. vol. 11. -

Chapter 3. Glass and Other Vitreous Materials Through History

EMU Notes in Mineralogy, Vol. 20 (2019), Chapter 3, 87–150 Glass and other vitreous materials through history Ivana ANGELINI1, Bernard GRATUZE2 and Gilberto ARTIOLI3 1Department of Cultural Heritage, Universita` di Padova, Piazza Capitaniato 7, 35139 Padova, Italy [email protected] 2CNRS, Universite´ d’Orle´ans, IRAMAT-CEB, 3D rue de la Fe´rollerie, F-45071, Orle´ans Cedex 2, France [email protected] 3Department of Geosciences and CIRCe Centre, Universita` di Padova, Via Gradenigo 6, 35131 Padova, Italy [email protected] Early vitreous materials include homogeneous glass, glassy faience, faience and glazed stones. These materials evolved slowly into more specialized substances such as enamels, engobes, lustres, or even modern metallic glass. The nature and properties of vitreous materials are summarized briefly, with an eye to the historical evolution of glass production in the Mediterranean world. Focus is on the evolution of European, Egyptian, and Near East materials. Notes on Chinese and Indian glass are reported for comparison. The most common techniques of mineralogical and chemical characterization of vitreous materials are described, highlighting the information derived for the purposes of archaeometric analysis and conservation. 1. Introduction: chemistry, mineralogy and texture of vitreous materials Glass is a solid material that does not have long-range order in the atomic arrangement, as opposed to crystalline solids having ordered atomic configurations on a lattice (Doremus, 1994; Shelby, 2005). It has been shown experimentally (Huang et al., 2012) that amorphous solids can be described adequately by the model proposed by Zachariasen, the so-called random network theory (Zachariasen, 1932). Because of the contribution of configurational entropy, glass has a higher Gibbs free energy than a solid with the same composition.