Stone Axe Studies in Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

£2.00 North West Mountain Rescue Team Intruder Alarms Portable Appliance Testing Approved Contractor Fixed Wire Testing

north west mountain rescue team ANNUAL REPORT 2013 REPORT ANNUAL Minimum Donation nwmrt £2.00 north west mountain rescue team Intruder Alarms Portable Appliance Testing Approved Contractor Fixed Wire Testing AA Electrical Services Domestic, Industrial & Agricultural Installation and Maintenance Phone: 028 2175 9797 Mobile: 07736127027 26b Carncoagh Road, Rathkenny, Ballymena, Co Antrim BT43 7LW 10% discount on presentation of this advert The three Tavnaghoney Cottages are situated in beautiful Glenaan in the Tavnaghoney heart of the Antrim Glens, with easy access to the Moyle Way, Antrim Hills Cottages & Causeway walking trails. Each cottage offers 4-star accommodation, sleeping seven people. Downstairs is a through lounge with open plan kitchen / dining, a double room (en-suite), a twin room and family bathroom. Upstairs has a triple room with en-suite. All cottages are wheelchair accessible. www.tavnaghoney.com 2 experience the magic of geological time travel www.marblearchcavesgeopark.com Telephone: +44 (0) 28 6634 8855 4 Contents 6-7 Foreword Acknowledgements by Davy Campbell, Team Leader Executive Editor 8-9 nwmrt - Who we are Graeme Stanbridge by Joe Dowdall, Operations Officer Editorial Team Louis Edmondson 10-11 Callout log - Mountain, Cave, Cliff and Sea Cliff Rescue Michael McConville Incidents 2013 Catherine Scott Catherine Tilbury 12-13 Community events Proof Reading Lowland Incidents Gillian Crawford 14-15 Search and Rescue Teams - Where we fit in Design Rachel Beckley 16-17 Operations - Five Days in March Photography by Graeme Stanbridge, Chairperson Paul McNicholl Anthony Murray Trevor Quinn 18-19 Snowbound by Archie Ralston President Rotary Club Carluke 20 Slemish Challenge 21 Belfast Hills Walk 23 Animal Rescue 25 Mountain Safety nwmrt would like to thank all our 28 Contact Details supporters, funders and sponsors, especially Sports Council NI 5 6 Foreword by Davy Campbell, Team Leader he north west mountain rescue team was established in Derry City in 1980 to provide a volunteer search and rescue Tservice for the north west of Northern Ireland. -

APRIL 2020 I Was Hungry and You Gave Me Something to Eat Matthew 25:35

APRIL 2020 I was hungry and you gave me something to eat Matthew 25:35 Barnabas stands alongside our Christian brothers and sisters around the world where they suffer discrimination and persecution. By providing aid through our Christian partners on the ground, we are able to maintain our overheads at less than 12% of our income. Please help us to help those who desperately need relief from their suffering. Barnabas Fund Donate online at: is a company Office 113, Russell Business Centre, registered in England 40-42 Lisburn Road, Belfast BT9 6AA www.barnabasaid.org/herald Number 04029536. Registered Charity [email protected] call: 07875 539003 Number 1092935 CONTENTS | APRIL 2020 FEATURES 12 Shaping young leaders The PCI Intern Scheme 16 Clubbing together A story from Bray Presbyterian 18 He is risen An Easter reflection 20 A steep learning curve A story from PCI’s Leaders in Training scheme 22 A shocking home truth New resource on tackling homelessness 34 Strengthening your pastoral core Advice for elders on Bible use 36 Equipping young people as everyday disciples A shocking home truth p22 Prioritising discipleship for young people 38 A San Francisco story Interview with a Presbyterian minister in California 40 Debating the persecution of Christians Report on House of Commons discussion REGULARS A San Francisco story p38 Debating the persecution of Christians p40 4 Letters 6 General news CONTRIBUTORS 8 In this month… Suzanne Hamilton is Tom Finnegan is the Senior Communications Training Development 9 My story Assistant for the Herald. Officer for PCI. In this role 11 Talking points She attends Ballyholme Tom develops and delivers Presbyterian in Bangor, training and resources for 14 Life lessons is married to Steven and congregational life and 15 Andrew Conway mum to twin boys. -

The Prehistoric Burial Sites of Northern Ireland

The Prehistoric Burial Sites of Northern Ireland Harry and June Welsh Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 006 8 ISBN 978 1 78491 007 5 (e-Pdf) © Archaeopress, H and J Welsh 2014 Cover photo: portal tomb, Ballykeel in County Armagh All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by CMP (UK) Ltd This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents Introduction �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Background and acknowledgements ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 A short history of prehistoric archaeology in northern ireland ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Northern ireland’s prehistory in context....................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Classifications used in the inventory............................................................................................................................ -

Program of the 76Th Annual Meeting

PROGRAM OF THE 76 TH ANNUAL MEETING March 30−April 3, 2011 Sacramento, California THE ANNUAL MEETING of the Society for American Archaeology provides a forum for the dissemination of knowledge and discussion. The views expressed at the sessions are solely those of the speakers and the Society does not endorse, approve, or censor them. Descriptions of events and titles are those of the organizers, not the Society. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Published by the Society for American Archaeology 900 Second Street NE, Suite 12 Washington DC 20002-3560 USA Tel: +1 202/789-8200 Fax: +1 202/789-0284 Email: [email protected] WWW: http://www.saa.org Copyright © 2011 Society for American Archaeology. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting 3 Contents 4................ Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting Agenda 5………..….2011 Award Recipients 11.................Maps of the Hyatt Regency Sacramento, Sheraton Grand Sacramento, and the Sacramento Convention Center 17 ................Meeting Organizers, SAA Board of Directors, & SAA Staff 18 ............... General Information . 20. .............. Featured Sessions 22 ............... Summary Schedule 26 ............... A Word about the Sessions 28…………. Student Events 29………..…Sessions At A Glance (NEW!) 37................ Program 169................SAA Awards, Scholarships, & Fellowships 176................ Presidents of SAA . 176................ Annual Meeting Sites 178................ Exhibit Map 179................Exhibitor Directory 190................SAA Committees and Task Forces 194…….…….Index of Participants 4 Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting APRIL 1, 2011 5 PM Call to Order Call for Approval of Minutes of the 2010 Annual Business Meeting Remarks President Margaret W. -

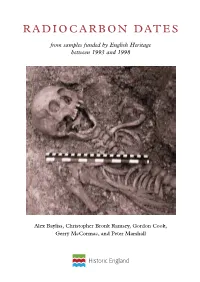

Radiocarbon Dates 1993-1998

RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBONDATES RADIOCARBON DATES This volume holds a datelist of 1063 radiocarbon determinations carried out between 1993 and 1998 on behalf of the Ancient Monuments Laboratory of English Heritage. It contains supporting information about the samples and the sites producing them, a comprehensive bibliography, and two indexes for reference from samples funded by English Heritage and analysis. An introduction provides discussion of the character and taphonomy between 1993 and 1998 of the dated samples and information about the methods used for the analyses reported and their calibration. The datelist has been collated from information provided by the submitters of the samples and the dating laboratories. Many of the sites and projects from which dates have been obtained are now published, although developments in statistical methodologies for the interpretation of radiocarbon dates since these measurements were made may allow revised chronological models to be constructed on the basis of these dates. The purpose of this volume is to provide easy access to the raw scientific and contextual data which may be used in further research. Alex Bayliss, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, Gordon Cook, Gerry McCormac, and Peter Marshall Front cover:Wharram Percy cemetery excavations. (©Wharram Research Project) Back cover:The Scientific Dating Research Team visiting Stonehenge as part of Science, Engineering, and Technology Week,March 1996. Left to right: Stephen Hoper (The Queen’s University, Belfast), Christopher Bronk Ramsey (Oxford -

The Neolithic and Early Bronze Age

THE NEOLITHIC AND EARLY BRONZE AGE IN THE FIRTH OF CLYDE ISOBEL MARY HUGHES VOLUMEI Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph. D. Department of Archaeology The University of Glasgow October 1987 0 Isobel M Hughes, 1987. In memory of my mother, and of my father - John Gervase Riddell M. A., D. D., one time Professor of Divinity, University of Glasgow. 7727 LJ r'- I 1GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY i CONTENTS i " VOLUME I LIST OF TABLES xii LIST OF FIGURES xvi LIST OF PLATES xix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xx SUMMARY xxii PREFACE xxiv CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Field of Enquiry 1.2 Approaches to a Social Archaeology 1.2.1 Introduction 1.2.2 Understanding Change 1.2.3 The Nature of the Evidence 1.2.4 Megalithic Cairns and Neolithic Society 1.2.5 Monuments -a Lasting Impression 1.2.6 The Emergence of Individual Power 1.3 Aims, Objectives and Methodology 11 ý1 t ii CHAPTER2 AREA OF STUDY - PHYSICAL FEATURES 20 2.1 Location and Extent 2.2 Definition 2.3 Landforms 2.3.1 Introduction 2.3.2 Highland and Island 2.3.3 Midland Valley 2.3.4 Southern Upland 2.3.5 Climate 2.4 Aspects of the Environment in Prehistory 2.4.1 Introduction 2.4.2 Raised Beach Formation 2.4.3 Vegetation 2.4.4 Climate 2.4.5 Soils CHAPTER 3 FORMATION OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD 38 3.1 Introduction 3.1.1 Definition 3.1.2 Initiation 3.1.3 Social and Economic Change iii 3.2 Period before 1780 3.2.1 The Archaeological Record 3.2.2 Social and Economic Development 3.3 Period 1780 - 1845 3.3.1 The Archaeological Record 3.3.2 Social and Economic Development 3.4 Period 1845 - 1914 3.4.1 Social and Economic -

Sacred Places Europe: 108 Destinations

Reviews from Sacred Places Around the World “… the ruins, mountains, sanctuaries, lost cities, and pilgrimage routes held sacred around the world.” (Book Passage 1/2000) “For each site, Brad Olsen provides historical background, a description of the site and its special features, and directions for getting there.” (Theology Digest Summer, 2000) “(Readers) will thrill to the wonderful history and the vibrations of the world’s sacred healing places.” (East & West 2/2000) “Sites that emanate the energy of sacred spots.” (The Sunday Times 1/2000) “Sacred sites (to) the ruins, sanctuaries, mountains, lost cities, temples, and pilgrimage routes of ancient civilizations.” (San Francisco Chronicle 1/2000) “Many sacred places are now bustling tourist and pilgrimage desti- nations. But no crowd or souvenir shop can stand in the way of a traveler with great intentions and zero expectations.” (Spirituality & Health Summer, 2000) “Unleash your imagination by going on a mystical journey. Brad Olsen gives his take on some of the most amazing and unexplained spots on the globe — including the underwater ruins of Bimini, which seems to point the way to the Lost City of Atlantis. You can choose to take an armchair pilgrimage (the book is a fascinating read) or follow his tips on how to travel to these powerful sites yourself.” (Mode 7/2000) “Should you be inspired to make a pilgrimage of your own, you might want to pick up a copy of Brad Olsen’s guide to the world’s sacred places. Olsen’s marvelous drawings and mysterious maps enhance a package that is as bizarre as it is wonderfully acces- sible. -

Memory and Monuments at the Hill of Tara

Memory and Monuments at the Hill of Tara Memory and Monuments at the Hill of Tara Erin McDonald This article focuses on the prehistoric monuments located at the ‘royal’ site of Tara in Meath, Ireland, and their significance throughout Irish prehistory. Many of the monuments built during later prehistory respect and avoid earlier constructions, suggesting a cultural memory of the site that lasted from the Neolithic into the Early Medieval period. Understanding the chronology of the various monuments is necessary for deciphering the palimpsest that makes up the landscape of Tara. Based on the reuse, placement and types of monuments at the Hill of Tara, it may be possible to speculate on the motivations and intentions of the prehistoric peoples who lived in the area. Institute for European and Mediterranean Archaeology 55 Erin McDonald This article focuses on the prehistoric and the work of the Discovery Programme, early historic monuments located at the relatively little was known about the ‘royal’ site of the Hill of Tara in County archaeology of Tara. Seán Ó Ríordáin Meath, Ireland, and the significance of the carried out excavations of Duma na nGiall monuments throughout and after the main and Ráith na Senad, but died before he period of prehistoric activity at Tara. The could publish his findings.6 In recent years, Hill of Tara is one of the four ‘royal’ sites Ó Ríordáin’s notes have been compiled from the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age into site reports and excavated material was in Ireland, and appears to have played an utilized for radiocarbon dating.7 important role in ritual and ceremonial activity, more so than the other ‘royal’ sites; medieval literature suggests that Tara had a crucial role in the inauguration of Irish kings.1 Many of the monuments built on the Hill of Tara during the later prehistoric period respect or incorporate earlier monuments, suggesting a cultural memory of the importance of the Hill of Tara that lasted from the Neolithic to the Early Medieval Period. -

Outdoor Recreation Action Plan for the Sperrins (ORNI on Behalf of Sportni, 2013)

Mid Ulster District Council Outdoor Recreation Strategic Plan Prepared by Outdoor Recreation NI on behalf of Mid Ulster District Council October 2019 CONTENTS CONTENTS ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 TABLE OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLE OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 ACRONYMS ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 FOREWORD ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................12 1.2 Aim ....................................................................................................................................................12 1.3 Objectives .........................................................................................................................................13 -

Sacred Places Europe: 108 Destinations

Reviews from Sacred Places Around the World “… the ruins, mountains, sanctuaries, lost cities, and pilgrimage routes held sacred around the world.” (Book Passage 1/2000) “For each site, Brad Olsen provides historical background, a description of the site and its special features, and directions for getting there.” (Theology Digest Summer, 2000) “(Readers) will thrill to the wonderful history and the vibrations of the world’s sacred healing places.” (East & West 2/2000) “Sites that emanate the energy of sacred spots.” (The Sunday Times 1/2000) “Sacred sites (to) the ruins, sanctuaries, mountains, lost cities, temples, and pilgrimage routes of ancient civilizations.” (San Francisco Chronicle 1/2000) “Many sacred places are now bustling tourist and pilgrimage desti- nations. But no crowd or souvenir shop can stand in the way of a traveler with great intentions and zero expectations.” (Spirituality & Health Summer, 2000) “Unleash your imagination by going on a mystical journey. Brad Olsen gives his take on some of the most amazing and unexplained spots on the globe — including the underwater ruins of Bimini, which seems to point the way to the Lost City of Atlantis. You can choose to take an armchair pilgrimage (the book is a fascinating read) or follow his tips on how to travel to these powerful sites yourself.” (Mode 7/2000) “Should you be inspired to make a pilgrimage of your own, you might want to pick up a copy of Brad Olsen’s guide to the world’s sacred places. Olsen’s marvelous drawings and mysterious maps enhance a package that is as bizarre as it is wonderfully acces- sible. -

Brass Bands of Ireland

Brass Bands of Ireland St Patrick’s Brass Band, Waterford a historical directory Gavin Holman 1st edition, January 2019 Introduction Of the many brass bands that have flourished in Ireland over the last 200 years very few have documented records covering their history. This directory is an attempt to collect together information about such bands and make it available to all. Over 1,370 bands are recorded here (93 currently active), with some 356 additional cross references for alternative or previous names. This volume is an extracted subset of my earlier “Brass Bands of the British Isles – a Historical Directory” (2018). Where "active" dates are given these indicate documented appearances - the bands may well have existed beyond those dates quoted. Bands which folded for more than 1 year (apart from during WW1 or WW2) with a successor band being later formed are regarded as "extinct". “Still active” indicates that there is evidence for continuous activity for that band in the previous years up to that date. Minor name variations, e.g. X Brass Band, X Silver Band, X Silver Prize Band, are generally not referenced, unless it is clear that they were separate entities. Various bands have changed their names several times over the years, making tracking them down more difficult. Where there is more than one instance of a specific brass band’s name, this is indicated by a number suffix – e.g. (1), (2) to indicate the order of appearance of the bands. Ballyclare Brass Band currently holds the record for Irish bands with (3). If the location is not inherent or obvious from the band's name, then the particular village or town is indicated, otherwise only the relevant county. -

Estimating the Scale of Stone Axe Production: a Case Study from Onega Lake, Russian Karelia Alexey Tarasov 1 and Sergey Stafeev 2

Estimating the scale of stone axe production: A case study from Onega Lake, Russian Karelia Alexey Tarasov 1 and Sergey Stafeev 2 1. Institute of Linguistics, Literature and History, Pushkinskaya st.11, 185910 Petrozavodsk, Russia, Email: [email protected] 2. Institute of Applied Mathematical Research, Pushkinskaya st.11, 185910 Petrozavodsk, Russia, Email: [email protected] Abstract: The industry of metatuff axes and adzes on the western coast of Onega Lake (Eneolithic period, ca. 3500 – 1500 cal. BC) allows assuming some sort of craft specialization. Excavations of a workshop site Fofanovo XIII, conducted in 2010-2011, provided an extremely large assemblage of artefacts (over 350000 finds from just 30 m2, mostly production debitage). An attempt to estimate the output of production within the excavated area is based on experimental data from a series of replication experiments. Mass-analysis with the aid of image recognition software was used to obtain raw data from flakes from excavations and experiments. Statistical evaluation assures that the experimental results can be used as a basement for calculations. According to the proposed estimation, some 500 – 1000 tools could have been produced here, and this can be qualified as an evidence of “mass-production”. Keywords: Lithic technology; Neolithic; Eneolithic; Karelia; Fennoscandia; stone axe; adze; gouge; craft specialization; mass-analysis; image recognition 1. Introduction 1.1 Chopping tools of the Russian Karelian type; Cultural context and chronological framework This article is devoted to quite a small and narrow question, which belongs to a much wider set of problems associated with an industry of wood-chopping tools of the so-called Russian Karelian (Eastern Karelian) type from the territory of the present-day Republic of Karelia of the Russian Federation.