Memory and Monuments at the Hill of Tara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Celtic Encyclopedia, Volume II

7+( &(/7,& (1&<&/23(',$ 92/80( ,, . T H E C E L T I C E N C Y C L O P E D I A © HARRY MOUNTAIN VOLUME II UPUBLISH.COM 1998 Parkland, Florida, USA The Celtic Encyclopedia © 1997 Harry Mountain Individuals are encouraged to use the information in this book for discussion and scholarly research. The contents may be stored electronically or in hardcopy. However, the contents of this book may not be republished or redistributed in any form or format without the prior written permission of Harry Mountain. This is version 1.0 (1998) It is advisable to keep proof of purchase for future use. Harry Mountain can be reached via e-mail: [email protected] postal: Harry Mountain Apartado 2021, 3810 Aveiro, PORTUGAL Internet: http://www.CeltSite.com UPUBLISH.COM 1998 UPUBLISH.COM is a division of Dissertation.com ISBN: 1-58112-889-4 (set) ISBN: 1-58112-890-8 (vol. I) ISBN: 1-58112-891-6 (vol. II) ISBN: 1-58112-892-4 (vol. III) ISBN: 1-58112-893-2 (vol. IV) ISBN: 1-58112-894-0 (vol. V) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mountain, Harry, 1947– The Celtic encyclopedia / Harry Mountain. – Version 1.0 p. 1392 cm. Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-58112-889-4 (set). -– ISBN 1-58112-890-8 (v. 1). -- ISBN 1-58112-891-6 (v. 2). –- ISBN 1-58112-892-4 (v. 3). –- ISBN 1-58112-893-2 (v. 4). –- ISBN 1-58112-894-0 (v. 5). Celts—Encyclopedias. I. Title. D70.M67 1998-06-28 909’.04916—dc21 98-20788 CIP The Celtic Encyclopedia is dedicated to Rosemary who made all things possible . -

Irish Children's Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016

Irish Children’s Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016 A Thesis submitted to the School of English at the University of Dublin, Trinity College, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. February 2019 Rebecca Ann Long I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. _________________________________ Rebecca Long February 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………..i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………....iii INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………....4 CHAPTER ONE: RETRIEVING……………………………………………………………………………29 CHAPTER TWO: RE- TELLING……………………………………………………………………………...…64 CHAPTER THREE: REMEMBERING……………………………………………………………………....106 CHAPTER FOUR: RE- IMAGINING………………………………………………………………………........158 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………..……..210 WORKS CITED………………………….…………………………………………………….....226 Summary This thesis explores the recurring patterns of Irish mythological narratives that influence literature produced for children in Ireland following the Celtic Revival and into the twenty- first century. A selection of children’s books published between 1892 and 2016 are discussed with the aim of demonstrating the development of a pattern of retrieving, re-telling, remembering and re-imagining myths -

The Tara/Skryne Valley and the M3 Motorway; Development Vs. Heritage

L . o . 4 .0 «? ■ U i H NUI MAYNOOTH Qll*c«il n> h£jf**nn Ml Nuad The Tara/Skryne Valley and the M3 Motorway; Development vs. Heritage. Edel Reynolds 2005 Supervisor: Dr. Ronan Foley Head of Department: Professor James Walsh Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the M.A. (Geographical Analysis), Department of Geography, National University of Ireland, Maynooth. Abstract This thesis is about the conflict concerning the building of the MB motorway in an archaeologically sensitive area close to the Hill of Tara in Co. Meath. The main aim of this thesis was to examine the conflict between development and heritage in relation to the Tara/Skryne Valley; therefore the focus has been to investigate the planning process. It has been found that both the planning process and the Environmental Impact Assessment system in Ireland is inadequate. Another aspect of the conflict that was explored was the issue of insiders and outsiders. Through the examination of both quantitative and qualitative data, the conclusion has been reached that the majority of insiders, people from the Tara area, do in fact want the M3 to be built. This is contrary to the idea that was portrayed by the media that most people were opposed to the construction of the motorway. Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor, Ronan Foley, for all of his help and guidance over the last few months. Thanks to my parents, Helen and Liam and sisters, Anne and Nora for all of their encouragement over the last few months and particularly the last few days! I would especially like to thank my mother for driving me to Cavan on her precious day off, and for calming me down when I got stressed! Thanks to Yvonne for giving me the grand tour of Cavan, and for helping me carry out surveys there. -

Program of the 76Th Annual Meeting

PROGRAM OF THE 76 TH ANNUAL MEETING March 30−April 3, 2011 Sacramento, California THE ANNUAL MEETING of the Society for American Archaeology provides a forum for the dissemination of knowledge and discussion. The views expressed at the sessions are solely those of the speakers and the Society does not endorse, approve, or censor them. Descriptions of events and titles are those of the organizers, not the Society. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Published by the Society for American Archaeology 900 Second Street NE, Suite 12 Washington DC 20002-3560 USA Tel: +1 202/789-8200 Fax: +1 202/789-0284 Email: [email protected] WWW: http://www.saa.org Copyright © 2011 Society for American Archaeology. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting 3 Contents 4................ Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting Agenda 5………..….2011 Award Recipients 11.................Maps of the Hyatt Regency Sacramento, Sheraton Grand Sacramento, and the Sacramento Convention Center 17 ................Meeting Organizers, SAA Board of Directors, & SAA Staff 18 ............... General Information . 20. .............. Featured Sessions 22 ............... Summary Schedule 26 ............... A Word about the Sessions 28…………. Student Events 29………..…Sessions At A Glance (NEW!) 37................ Program 169................SAA Awards, Scholarships, & Fellowships 176................ Presidents of SAA . 176................ Annual Meeting Sites 178................ Exhibit Map 179................Exhibitor Directory 190................SAA Committees and Task Forces 194…….…….Index of Participants 4 Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting APRIL 1, 2011 5 PM Call to Order Call for Approval of Minutes of the 2010 Annual Business Meeting Remarks President Margaret W. -

The Heroic Biography of Cu Chulainn

THE HEROIC BIOGRAPHY OF CU CHULAINN. By Lisa Gibney B.A. NUl MAYNOOTH Ollicoil ni ft£ir«ann Mi ftuid FOR M.A IN MEDIEVAL IRISH HISTORY AND SOURCES, NUI MAYNOOTH, THE DEPARTMENT OF MEDIEVAL IRISH STUDIES, JULY 2004. DEPARTMENT HEAD: MCCONE, K SUPERVISOR: NI BHROLCHAIN,M 60094838 THE HEROIC BIOGRAPHY OF CU CHULAINN. By Lisa Gibney B.A. SPECIAL THANKS TO: Ann Gibney, Claire King, Mary Lenanne, Roisin Morley, Muireann Ni Bhrolchain, Mary Coolen and her team at the Drumcondra Physiotherapy Clinic. CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2 2. Heroic Biography 8 3. Conception and Birth: Compert Con Culainn 18 4. Youth and Life Endangered: Macgnimrada 23 Con Culainn 5. Acquires a wife: Tochmarc Emere 32 6. Visit to Otherworld, Exile and Return: 35 Tochmarc Emere and Serglige Con Culainn 7. Death and Invulnerability: Brislech Mor Maige 42 Muirthemne 8. Conclusion 46 9. Bibliogrpahy 47 i INTRODUCTION Early Irish literature is romantic, idealised, stylised and gruesome. It shows a tension between reality and fantasy ’which seem to me to be usually an irresolvable dichotomy. The stories set themselves in pre-history. It presents these texts as a “window on the iron age”2. The writers may have been Christians distancing themselves from past heathen ways. This backward glance maybe taken from the literature tradition in Latin transferred from the continent and read by Irish scholars. Where the authors “undertake to inform the audience concerning the pagan past, characterizing it as remote, alien and deluded”3 or were they diligent scholars trying to preserve the past. This question is still debateable. The stories manage to be set in both the past and the present, both historical Ireland with astonishingly accuracy and the mythical otherworld. -

The Bronze Age in Europe : Gods, Heroes and Treasures Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE BRONZE AGE IN EUROPE : GODS, HEROES AND TREASURES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jean-Pierre Mohen | 160 pages | 27 Nov 2000 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500301012 | English | London, United Kingdom The Bronze Age in Europe : Gods, Heroes and Treasures PDF Book One was gushing with milk, one with wine, while the third flowed with fragrant oil; and the fourth ran with water, which grew warm at the setting of the Pleiads, and in turn at their rising bubbled forth from the hollow rock, cold as crystal. In the myth of Perseus , the hero is dispatched on an apparent suicide mission by evil King Polydectes to kill and gain the head of the only mortal Gorgon, Medusa, whose gaze turned men to stone. Crippled Hephaistos is led back to his mother Hera on Olympos by the god Dionysos, riding on an ass. However, one must be careful in how one interprets the idea of the spirits of the dead living in an 'underground' realm: Evidence from all of these cultures seems to suggest that this realm also had a reflected parallel existence to our own, and was also connected to the visible heavens and the concept of the far islands and shores of the world-river, called Okeanos by the Greeks…. Another site of equal pagan importance also lays claim to this, however: The Hill of Uisneach , visible from Croghan across the sprawling boglands of Allen:. One must not forget that the Caucasus and Asia Minor was a historic homeland of metalcraft and weapon-crafting, as well as horsemanship. An ice age is a period of colder global temperatures and recurring glacial expansion capable of lasting hundreds of millions of years. -

Nostalgia and the Irish Fairy Landscape

The land of heart’s desire: Nostalgia and the Irish fairy landscape Hannah Claire Irwin BA (Media and Cultural Studies), B. Media (Hons 1) Macquarie University This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Media and Cultural Studies. Faculty of Arts, Department of Media, Music, Communication and Cultural Studies, Macquarie University, Sydney August 2017 2 Table of Contents Figures Index 6 Abstract 7 Author Declaration 8 Acknowledgments 9 Introduction: Out of this dull world 1.1 Introduction 11 1.2 The research problem and current research 12 1.3 The current field 13 1.4 Objective and methodology 14 1.5 Defining major terms 15 1.6 Structure of research 17 Chapter One - Literature Review: Hungry thirsty roots 2.1 Introduction 20 2.2 Early collections (pre-1880) 21 2.3 The Irish Literary Revival (1880-1920) 24 2.4 Movement from ethnography to analysis (1920-1990) 31 2.5 The ‘new fairylore’ (post-1990) 33 2.6 Conclusion 37 Chapter Two - Theory: In a place apart 3.1 Introduction 38 3.2 Nostalgia 39 3.3 The Irish fairy landscape 43 3 3.4 Space and place 49 3.5 Power 54 3.6 Conclusion 58 Chapter Three - Nationalism: Green jacket, red cap 4.1 Introduction 59 4.2 Nationalism and the power of place 60 4.3 The wearing of the green: Evoking nostalgia for Éire 63 4.4 The National Leprechaun Museum 67 4.5 The Last Leprechauns of Ireland 74 4.6 Critique 81 4.7 Conclusion 89 Chapter Four - Heritage: Up the airy mountain 5.1 Introduction 93 5.2 Heritage and the conservation of place 94 5.3 Discovering Ireland the ‘timeless’: Heritage -

Give up IRA Tapes

January 2012 VOL. 23 #1 $1.50 Boston’s hometown journal of Irish culture. Worldwide at bostonirish.com All contents copyright © 2012 Boston Neighborhood News, Inc. Judge to BC: Give up IRA tapes By Bill Forry Managing editor A federal judge in Boston has told Boston College that it must turn over recordings and other documents that are part of an oral history collection kept at the university’s Burns Library. The ruling is a major setback for BC and its allies who had sought to quash a subpoena triggered by a British re- quest to view the documents as part of a criminal investigation into sectarian It was the round trip to Ireland made by the USS Jamestown, pictured in the accompanying sketch sailing into Cobh, murders during the Troubles. Co. Cork on April 12, 1847, that highlighted Irish famine relief efforts out of Boston. Laden with 800 tons of provisions The subpoena in question, issued and supplies worth $35,000, the Jamestown landed to jubilant greetings. last May and June, sought the records Portrait of the USS Jamestown by E.D.Walker, Marine Artist related to two individuals, Brendan Hughes and Dolours Price, both of whom were alleged to be former IRA ‘With Good Will Doing Service’ defines members. BC has already handed over documents involving Hughes, who died three years ago. The Charitable Irish Society of Boston Court documents indicate that the cur- The Charitable Irish Society of Boston Irishmen and their equivalent of $500 today, and dues were rent investigation focuses on the killing (CIS) is the oldest Irish organization descendants in the 8 shillings annually, the equivalent of of Jean McConville, a Belfast mother in the Americas and will celebrate its Massachusetts colony $400 today. -

A Few Words from the Editor Welcome to Our Winter Issue of Irish Roots

Irish Roots 2015 Number 4 Irish Roots A few words from the editor Welcome to our Winter issue of Irish Roots. Where Issue No 4 2015 ISSN 0791-6329 on earth did that year disappear to? As the 1916 commemorations get ready to rumble CONTENTS we mark this centenary year with a new series by Sean Murphy who presents family histories of leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising, page 6. We 4 News introduce another fascinating series featuring sacred sites of Ireland and we begin with a visit to the Hill of Uisneach in County Westmeath, a place of great significance in 5 And Another Thing the history and folklore of Ireland, page 8. Patrick Roycroft fuses genealogy and geology on page 16 and Judith Eccles Wight helps to keep you on track with researching your railroad ancestors 6 1916 Leaders Family Histories in the US, page 22. We remember the Cullen brothers who journeyed from the small townland of Ballynastockan in Co. Wicklow to Minneapolis, US, 8 Sacred Sites Of Ireland bringing with them their remarkable stone cutting skills, their legacy lives on in beautiful sculptures to this day and for generations to come, page 24. Staying in Co. Wicklow we share the story of how the lost WW1 medals of a young 10 Tracing Your Roscommon Ancestors soldier were finally reunited with his granddaughter many years later, page 30. Our regular features include, ‘And another Thing’ with Steven Smyrl on the saga of the release of the Irish 1926 census, page 5. James Ryan helps us to 12 ACE Summer Schools trace our Roscommon ancestors, page 10 and Claire Santry keeps us posted with all the latest in Irish genealogy, page 18. -

The Changing Face of Neolithic and Bronze Age Ireland: a Big Data Approach to the Settlement and Burial Records

The Changing Face of Neolithic and Bronze Age Ireland: A Big Data Approach to the Settlement and Burial Records McLaughlin, T., Whitehouse, N., Schulting, R. J., McClatchie, M., & Barratt, P. (2016). The Changing Face of Neolithic and Bronze Age Ireland: A Big Data Approach to the Settlement and Burial Records. Journal of World Prehistory. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10963-016-9093-0 Published in: Journal of World Prehistory Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. -

Ireland from the Beginning I

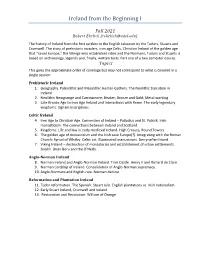

Ireland from the Beginning I Fall 2021 Robert Ehrlich ([email protected]) The history of Ireland from the first settlers to the English takeover by the Tudors, Stuarts and Cromwell. The story of prehistoric invaders, iron age Celts, Christian Ireland of the golden age that “saved Europe,” the Vikings who established cities and the Normans, Tudors and Stuarts is based on archaeology, legends and, finally, written texts. Part one of a two semester course. Topics This gives the approximate order of coverage but may not correspond to what is covered in a single session. Prehistoric Ireland 1. Geography. Paleolithic and Mesolithic Hunter-Gathers. The Neolithic transition in Ireland 2. Neolithic Newgrange and Carrowmore; Beaker, Bronze and Gold; Metal working 3. Late Bronze Age to Iron Age Ireland and interactions with Rome. The early legendary kingdoms. Ogham inscriptions. Celtic Ireland 4. Iren Age to Christian Age. Conversion of Ireland – Palladius and St. Patrick. Irish monasticism. The connections between Ireland and Scotland. 5. Kingdoms. Life and law in early medieval Ireland. High Crosses, Round Towers 6. The golden age of monasticism and the Irish save Europe(?). Integrating with the Roman Church: Synod of Whitby. Celtic art. Illuminated manuscripts. Derrynaflan Hoard 7. Viking Ireland – destruction of monasteries and establishment of urban settlements. Dublin. Brian Boru and the O’Neills. Anglo-Norman Ireland 8. Norman Ireland and Anglo-Norman Ireland. Trim Castle. Henry II and Richard de Clare. 9. Norman Lordship of Ireland. Consolidation of Anglo-Norman supremacy. 10. Anglo-Normans and English rule. Norman decline. Reformation and Plantation Ireland 11. Tudor reformation. The Spanish. -

The Song of the Silver Branch: Healing the Human-Nature Relationship in the Irish Druidic Tradition

The Song of the Silver Branch: Healing the Human-Nature Relationship in the Irish Druidic Tradition Jason Kirkey Naropa University Interdisciplinary Studies November 29th, 2007 Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. —John Keats1 To be human, when being human is a habit we have broken, that is a wonder. —John Moriarty2 At the Hill of Tara in the sacred center of Ireland a man could be seen walking across the fields toward the great hall, the seat of the high king. Not any man was this, but Lúgh. He came because the Fomorian people made war with the Tuatha Dé Danann, two tribes of people living in Ireland. A war between dark and light. A war between two people experiencing the world in two opposing ways. The Tuatha Dé, content to live with nature, ruled only though the sovereignty of the land. The Fomorians, not so content, were possessed with Súil Milldagach, the destructive eye which eradicated anything it looked upon, were intent on ravaging the land. Lúgh approached the doorkeeper at the great hall who was instructed not to let any man pass the gates who did not possess an art. Not only possessing of an art, but one which was not already possessed by someone within the hall. The doorkeeper told this to Lúgh who replied, “Question me doorkeeper, I am a warrior.” But there was a warrior at Tara already. “Question me doorkeeper, I am a smith,” but there was already a smith. “Question me doorkeeper,” said Lúgh again, “I am a poet,” and again the doorkeeper replied that there was a poet at Tara already.