The Song of the Silver Branch: Healing the Human-Nature Relationship in the Irish Druidic Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Celtic Encyclopedia, Volume II

7+( &(/7,& (1&<&/23(',$ 92/80( ,, . T H E C E L T I C E N C Y C L O P E D I A © HARRY MOUNTAIN VOLUME II UPUBLISH.COM 1998 Parkland, Florida, USA The Celtic Encyclopedia © 1997 Harry Mountain Individuals are encouraged to use the information in this book for discussion and scholarly research. The contents may be stored electronically or in hardcopy. However, the contents of this book may not be republished or redistributed in any form or format without the prior written permission of Harry Mountain. This is version 1.0 (1998) It is advisable to keep proof of purchase for future use. Harry Mountain can be reached via e-mail: [email protected] postal: Harry Mountain Apartado 2021, 3810 Aveiro, PORTUGAL Internet: http://www.CeltSite.com UPUBLISH.COM 1998 UPUBLISH.COM is a division of Dissertation.com ISBN: 1-58112-889-4 (set) ISBN: 1-58112-890-8 (vol. I) ISBN: 1-58112-891-6 (vol. II) ISBN: 1-58112-892-4 (vol. III) ISBN: 1-58112-893-2 (vol. IV) ISBN: 1-58112-894-0 (vol. V) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mountain, Harry, 1947– The Celtic encyclopedia / Harry Mountain. – Version 1.0 p. 1392 cm. Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-58112-889-4 (set). -– ISBN 1-58112-890-8 (v. 1). -- ISBN 1-58112-891-6 (v. 2). –- ISBN 1-58112-892-4 (v. 3). –- ISBN 1-58112-893-2 (v. 4). –- ISBN 1-58112-894-0 (v. 5). Celts—Encyclopedias. I. Title. D70.M67 1998-06-28 909’.04916—dc21 98-20788 CIP The Celtic Encyclopedia is dedicated to Rosemary who made all things possible . -

Irish Children's Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016

Irish Children’s Literature and the Poetics of Memory, 1892-2016 A Thesis submitted to the School of English at the University of Dublin, Trinity College, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. February 2019 Rebecca Ann Long I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. _________________________________ Rebecca Long February 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………..i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………....iii INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………....4 CHAPTER ONE: RETRIEVING……………………………………………………………………………29 CHAPTER TWO: RE- TELLING……………………………………………………………………………...…64 CHAPTER THREE: REMEMBERING……………………………………………………………………....106 CHAPTER FOUR: RE- IMAGINING………………………………………………………………………........158 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………..……..210 WORKS CITED………………………….…………………………………………………….....226 Summary This thesis explores the recurring patterns of Irish mythological narratives that influence literature produced for children in Ireland following the Celtic Revival and into the twenty- first century. A selection of children’s books published between 1892 and 2016 are discussed with the aim of demonstrating the development of a pattern of retrieving, re-telling, remembering and re-imagining myths -

Stories from Early Irish History

1 ^EUNIVERJ//, ^:IOS- =s & oo 30 r>ETRr>p'S LAMENT. A Land of Heroes Stories from Early Irish History BY W. LORCAN O'BYRNE WITH SIX ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN E. BACON BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED LONDON GLASGOW AND DUBLIN n.-a INTEODUCTION. Who the authors of these Tales were is unknown. It is generally accepted that what we now possess is the growth of family or tribal histories, which, from being transmitted down, from generation to generation, give us fair accounts of actual events. The Tales that are here given are only a few out of very many hundreds embedded in the vast quantity of Old Gaelic manuscripts hidden away in the libraries of nearly all the countries of Europe, as well as those that are treasured in the Royal Irish Academy and Trinity College, Dublin. An idea of the extent of these manuscripts may be gained by the statement of one, who perhaps had the fullest knowledge of them the late Professor O'Curry, in which he says that the portion of them (so far as they have been examined) relating to His- torical Tales would extend to upwards of 4000 pages of large size. This great mass is nearly all untrans- lated, but all the Tales that are given in this volume have already appeared in English, either in The Publications of the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language] the poetical versions of The IV A LAND OF HEROES. Foray of Queen Meave, by Aubrey de Vere; Deirdre', by Dr. Robert Joyce; The Lays of the Western Gael, and The Lays of the Red Branch, by Sir Samuel Ferguson; or in the prose collection by Dr. -

The Tara/Skryne Valley and the M3 Motorway; Development Vs. Heritage

L . o . 4 .0 «? ■ U i H NUI MAYNOOTH Qll*c«il n> h£jf**nn Ml Nuad The Tara/Skryne Valley and the M3 Motorway; Development vs. Heritage. Edel Reynolds 2005 Supervisor: Dr. Ronan Foley Head of Department: Professor James Walsh Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the M.A. (Geographical Analysis), Department of Geography, National University of Ireland, Maynooth. Abstract This thesis is about the conflict concerning the building of the MB motorway in an archaeologically sensitive area close to the Hill of Tara in Co. Meath. The main aim of this thesis was to examine the conflict between development and heritage in relation to the Tara/Skryne Valley; therefore the focus has been to investigate the planning process. It has been found that both the planning process and the Environmental Impact Assessment system in Ireland is inadequate. Another aspect of the conflict that was explored was the issue of insiders and outsiders. Through the examination of both quantitative and qualitative data, the conclusion has been reached that the majority of insiders, people from the Tara area, do in fact want the M3 to be built. This is contrary to the idea that was portrayed by the media that most people were opposed to the construction of the motorway. Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor, Ronan Foley, for all of his help and guidance over the last few months. Thanks to my parents, Helen and Liam and sisters, Anne and Nora for all of their encouragement over the last few months and particularly the last few days! I would especially like to thank my mother for driving me to Cavan on her precious day off, and for calming me down when I got stressed! Thanks to Yvonne for giving me the grand tour of Cavan, and for helping me carry out surveys there. -

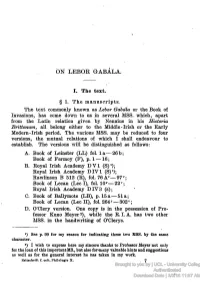

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

The Dagda As Briugu in Cath Maige Tuired

Deep Blue Deep Blue https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/documents Research Collections Library (University of Michigan Library) 2012-05 Following a Fork in the Text: the Dagda as briugu in Cath Maige Tuired Martin, Scott A. https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/138967 Downloaded from Deep Blue, University of Michigan's institutional repository Following a Fork in the Text: the Dagda as briugu in Cath Maige Tuired Scott A. Martin, May 2012 The description of the Dagda in §93 of Cath Maige Tuired has become iconic: the giant, slovenly man in a too-short tunic and crude horsehide shoes, dragging a huge club behind him. Several aspects of this depiction are unique to this text, including the language used to describe the Dagda’s odd weapon. The text presents it as a gabol gicca rothach, which Gray translates as a “wheeled fork.” In every other mention of the Dagda’s club – including the other references in CMT (§93 and §119) – the term used is lorg. DIL gives significantly different fields of reference for the two terms: 2 lorg denotes a staff, rod, club, handle of an implement, or “the membrum virile” (thus enabling the scatological pun Slicht Loirge an Dagdai, “Track of the Dagda’s Club/Penis”), while gabul bears a variety of definitions generally attached to the concept of “forking.” The attested compounds for gabul include gabulgicce, “a pronged pole,” with references to both the CMT usage and staves held by Conaire’s swineherds in Togail Bruidne Da Derga. DIL also mentions several occurrences of gabullorc, “a forked or pronged pole or staff,” including an occurrence in TBDD (where an iron gabullorg is carried by the supernatural Fer Caille) and another in Bretha im Fuillema Gell (“Judgements on Pledge-Interests”). -

Manx Place-Names: an Ulster View

37 Manx Place-Names: an Ulster View Kay Muhr In this chapter I will discuss place-name connections between Ulster and Man, beginning with the early appearances of Man in Irish tradition and its association with the mythological realm of Emain Ablach, from the 6th to the I 3th century. 1 A good introduction to the link between Ulster and Manx place-names is to look at Speed's map of Man published in 1605.2 Although the map is much later than the beginning of place-names in the Isle of Man, it does reflect those place-names already well-established 400 years before our time. Moreover the gloriously exaggerated Manx-centric view, showing the island almost filling the Irish sea between Ireland, Scotland, England and Wales, also allows the map to illustrate place-names from the coasts of these lands around. As an island visible from these coasts Man has been influenced by all of them. In Ireland there are Gaelic, Norse and English names - the latter now the dominant language in new place-names, though it was not so in the past. The Gaelic names include the port towns of Knok (now Carrick-) fergus, "Fergus' hill" or "rock", the rock clearly referring to the site of the medieval castle. In 13th-century Scotland Fergus was understood as the king whose migration introduced the Gaelic language. Further south, Dundalk "fort of the small sword" includes the element dun "hill-fort", one of three fortification names common in early Irish place-names, the others being rath "ring fort" and lios "enclosure". -

The Bronze Age in Europe : Gods, Heroes and Treasures Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE BRONZE AGE IN EUROPE : GODS, HEROES AND TREASURES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jean-Pierre Mohen | 160 pages | 27 Nov 2000 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500301012 | English | London, United Kingdom The Bronze Age in Europe : Gods, Heroes and Treasures PDF Book One was gushing with milk, one with wine, while the third flowed with fragrant oil; and the fourth ran with water, which grew warm at the setting of the Pleiads, and in turn at their rising bubbled forth from the hollow rock, cold as crystal. In the myth of Perseus , the hero is dispatched on an apparent suicide mission by evil King Polydectes to kill and gain the head of the only mortal Gorgon, Medusa, whose gaze turned men to stone. Crippled Hephaistos is led back to his mother Hera on Olympos by the god Dionysos, riding on an ass. However, one must be careful in how one interprets the idea of the spirits of the dead living in an 'underground' realm: Evidence from all of these cultures seems to suggest that this realm also had a reflected parallel existence to our own, and was also connected to the visible heavens and the concept of the far islands and shores of the world-river, called Okeanos by the Greeks…. Another site of equal pagan importance also lays claim to this, however: The Hill of Uisneach , visible from Croghan across the sprawling boglands of Allen:. One must not forget that the Caucasus and Asia Minor was a historic homeland of metalcraft and weapon-crafting, as well as horsemanship. An ice age is a period of colder global temperatures and recurring glacial expansion capable of lasting hundreds of millions of years. -

The Poetry of Geoffrey Bache Smith with Special Note of Tolkienian Contexts

Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 12 Issue 2 Article 2 2021 The Poetry of Geoffrey Bache Smith with Special Note of Tolkienian Contexts Kris Swank University of Glasgow, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Swank, Kris (2021) "The Poetry of Geoffrey Bache Smith with Special Note of Tolkienian Contexts," Journal of Tolkien Research: Vol. 12 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol12/iss2/2 This Conference Paper is brought to you for free and open access by ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Tolkien Research by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. The Poetry of Geoffrey Bache Smith with Special Note of Tolkienian Contexts Cover Page Footnote N.B. This paper grew from two directions: my PhD thesis work at the University of Glasgow under the direction of Dr. Dimitra Fimi, and conversations with John Garth beginning in Oxford during the summer of 2019. I’m grateful to both of them for their generosity and insights. This conference paper is available in Journal of Tolkien Research: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/ vol12/iss2/2 Swank: The Poetry of Geoffrey Bache Smith The Poetry of Geoffrey Bache Smith with Special Note of Tolkienian Contexts Kris Swank University of Glasgow presented at The Tolkien Symposium (May 8, 2021) sponsored by Tolkien@Kalamazoo, Dr. Christopher Vaccaro and Dr. Yvette Kisor, organizers The Voyage of Bran The Old Irish Voyage of Bran concerns an Otherworld voyage where, in one scene, Bran meets Manannán mac Ler, an Irish mythological figure who is often interpreted as a sea god. -

Order of Celtic Wolves Lesson 6

ORDER OF CELTIC WOLVES LESSON 6 Introduction Welcome to the sixth lesson. What a fantastic achievement making it so far. If you are enjoying the lessons let like-minded friends know. In this lesson, we are looking at the diet, clothing, and appearance of the Celts. We are also going to look at the complex social structure of the wolves and dispel some common notions about Alpha, Beta and Omega wolves. In the Bards section we look at the tales associated with Lugh. We will look at the role of Vates as healers, the herbal medicinal gardens and some ancient remedies that still work today. Finally, we finish the lesson with an overview of the Brehon Law of the Druids. I hope that there is something in the lesson that appeals to you. Sometimes head knowledge is great for General Knowledge quizzes, but the best way to learn is to get involved. Try some of the ancient remedies, eat some of the recipes, draw principles from the social structure of wolves and Brehon law and you may even want to dress and wear your hair like a Celt. Blessings to you all. Filtiarn Celts The Celtic Diet Athenaeus was an ethnic Greek and seems to have been a native of Naucrautis, Egypt. Although the dates of his birth and death have been lost, he seems to have been active in the late second and early third centuries of the common era. His surviving work The Deipnosophists (Dinner-table Philosophers) is a fifteen-volume text focusing on dining customs and surrounding rituals. -

Ogma's Tale: the Dagda and the Morrigan at the River Unius

Ogma’s Tale: The Dagda and the Morrigan at the River Unius Presented to Whispering Lake Grove for Samhain, October 30, 2016 by Nathan Large A tale you’ve asked, and a tale you shall have, of the Dagda and his envoy to the Morrigan. I’ve been tasked with the telling: lore-keeper of the Tuatha de Danann, champion to two kings, brother to the Good God, and as tied up in the tale as any… Ogma am I, this Samhain night. It was on a day just before Samhain that my brother and the dark queen met, he on his duties to our king, Nuada, and Lugh his battle master (and our half-brother besides). But before I come to that, let me set the stage. The Fomorians were a torment upon Eireann and a misery to we Tuatha, despite our past victory over the Fir Bolg. Though we gained three-quarters of Eireann at that first battle of Maige Tuireadh, we did not cast off the Fomor who oppressed the land. Worse, we also lost our king, Nuada, when the loss of his hand disqualified him from ruling. Instead, we accepted the rule of the half-Fomorian king, Bres, through whom the Fomorians exerted their control. Bres ruined the court of the Tuatha, stilling its songs, emptying its tables, and banning all competitions of skill. None of the court could perform their duties. I alone was permitted to serve, and that only to haul firewood for the hearth at Tara. Our first rejection of the Fomor was to unseat Bres, once Nuada was whole again, his hand restored. -

The Voyage of Bran Son of Febal

The Voyage of Bran Son of Febal to the Land of the Living AN OLD IRISH SAGA NOW FIRST EDITED, WITH TRANSLATION, NOTES, AND GLOSSARY, BY Kuno Meyer London: Published by David Nutt in the Strand [1895] The Voyage of Bran Son of Febal to the Land of the Living Page 1 INTRODUCTION THE old-Irish tale which is here edited and fully translated 1 for the first time, has come down to us in seven MSS. of different age and varying value. It is unfortunate that the oldest copy (U), that contained on p. 121a of the Leabhar na hUidhre, a MS. written about 1100 A.D., is a mere fragment, containing but the very end of the story from lil in chertle dia dernaind (§ 62 of my edition) to the conclusion. The other six MSS. all belong to a much later age, the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries respectively. Here follow a list and description of these MSS.:-- By R I denote a copy contained in the well-known Bodleian vellum quarto, marked Rawlinson B. 512, fo. 119a, 1-120b, 2. For a detailed description of this codex, see the Rolls edition of the Tripartite Life, vol. i. pp. xiv.-xlv. As the folios containing the copy of our text belong to that portion of the MS. which begins with the Baile in Scáil (fo. 101a), it is very probable that, like this tale, they were copied from the lost book of Dubdálethe, bishop of p. viii [paragraph continues] Armagh from 1049 to 1064. See Rev. Celt. xi.