The Cath Maige Tuired and the Vǫluspá

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stories from Early Irish History

1 ^EUNIVERJ//, ^:IOS- =s & oo 30 r>ETRr>p'S LAMENT. A Land of Heroes Stories from Early Irish History BY W. LORCAN O'BYRNE WITH SIX ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN E. BACON BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED LONDON GLASGOW AND DUBLIN n.-a INTEODUCTION. Who the authors of these Tales were is unknown. It is generally accepted that what we now possess is the growth of family or tribal histories, which, from being transmitted down, from generation to generation, give us fair accounts of actual events. The Tales that are here given are only a few out of very many hundreds embedded in the vast quantity of Old Gaelic manuscripts hidden away in the libraries of nearly all the countries of Europe, as well as those that are treasured in the Royal Irish Academy and Trinity College, Dublin. An idea of the extent of these manuscripts may be gained by the statement of one, who perhaps had the fullest knowledge of them the late Professor O'Curry, in which he says that the portion of them (so far as they have been examined) relating to His- torical Tales would extend to upwards of 4000 pages of large size. This great mass is nearly all untrans- lated, but all the Tales that are given in this volume have already appeared in English, either in The Publications of the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language] the poetical versions of The IV A LAND OF HEROES. Foray of Queen Meave, by Aubrey de Vere; Deirdre', by Dr. Robert Joyce; The Lays of the Western Gael, and The Lays of the Red Branch, by Sir Samuel Ferguson; or in the prose collection by Dr. -

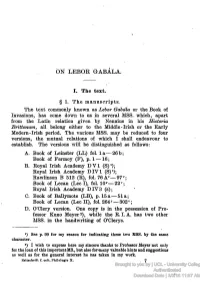

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

KINGS AGAINST CELTS Deliverance from Barbarians As a Theme In

KINGS AGAINST CELTS Deliverance from barbarians as a theme in Hellenistic royal propaganda Rolf Strootman Ieder nadeel heb z’n eigen voordeel – Johan Cruijff 1 Introduction The Celts, Polybios says, know neither law nor order, nor do they have any culture. 2 Other Greek writers, from Aristotle to Pausanias, agreed with him: the savage Celts were closer to animals than to civilised human beings. Therefore, when the Celts invaded Greece in 280-279 BC and attacked Delphi, Greeks saw this as an attack on Hellenic civilisation. Though the crisis was soon over, the image remained of inhuman barbarians who came from the dark edge of the earth to strike without warning at the centre of civilisation. This image was then exploited in political propaganda: first by the Aitolian League in Central Greece, then by virtually all the Greek-Macedonian kingdoms of that time. The 1 Several variants of this utterance of the ‘Oracle of Amsterdam’ (detriment is advantageous) are current in the Dutch language; this is the original version. Cf. H. Davidse ed., ‘Je moet schieten, anders kun je niet scoren’. Citaten van Johan Cruijff (The Hague 1999) 93; for some interesting linguistic remarks on Cruijff’s oracular sayings see G. Middag and K. van der Zwan, ‘“Utopieën wie nooit gebeuren”. De taal van Johan Cruijff’, Onze Taal 65 (1996) 275-7. 2 Polyb. 18.37.9. Greek authors use Keltoi and Galatai without any marked difference to denote these peoples, who evidently shared some common culture (e.g. infra Pausanias, but esp. 1.4.1; the first mention of Keltoi in Greek literature is in Hdt. -

The Dagda As Briugu in Cath Maige Tuired

Deep Blue Deep Blue https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/documents Research Collections Library (University of Michigan Library) 2012-05 Following a Fork in the Text: the Dagda as briugu in Cath Maige Tuired Martin, Scott A. https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/138967 Downloaded from Deep Blue, University of Michigan's institutional repository Following a Fork in the Text: the Dagda as briugu in Cath Maige Tuired Scott A. Martin, May 2012 The description of the Dagda in §93 of Cath Maige Tuired has become iconic: the giant, slovenly man in a too-short tunic and crude horsehide shoes, dragging a huge club behind him. Several aspects of this depiction are unique to this text, including the language used to describe the Dagda’s odd weapon. The text presents it as a gabol gicca rothach, which Gray translates as a “wheeled fork.” In every other mention of the Dagda’s club – including the other references in CMT (§93 and §119) – the term used is lorg. DIL gives significantly different fields of reference for the two terms: 2 lorg denotes a staff, rod, club, handle of an implement, or “the membrum virile” (thus enabling the scatological pun Slicht Loirge an Dagdai, “Track of the Dagda’s Club/Penis”), while gabul bears a variety of definitions generally attached to the concept of “forking.” The attested compounds for gabul include gabulgicce, “a pronged pole,” with references to both the CMT usage and staves held by Conaire’s swineherds in Togail Bruidne Da Derga. DIL also mentions several occurrences of gabullorc, “a forked or pronged pole or staff,” including an occurrence in TBDD (where an iron gabullorg is carried by the supernatural Fer Caille) and another in Bretha im Fuillema Gell (“Judgements on Pledge-Interests”). -

The History of Celtic Scholarship in Russia and the Soviet Union

THE HISTORY OF CELTIC SCHOLARSHIP IN RUSSIA AND THE SOVIET UNION SÉAMUS MAC MATHÚNA Mr Chairman, Colleagues, Ladies and Gentlemen, let me begin by thanking our distinguished Patron, Professor Karl Horst Schmidt, for agreeing to open this inaugural conference of Societas Celto-Slavica. We are greatly honoured by his presence here today and we thank him most sincerely for his excellent introduction and kind words regarding the formation of the Society. 0. Introduction I thought initially it would be possible in my lecture this morning to give a brief outline of the main works and achievements of Celtic scholarship in the Slavic countries, secure in the knowledge that it would not be necessary to discuss Celtic Studies in Poland as this subject would be dealt with by Professor Piotr Stalmaszczyk in a subsequent paper.1 However, having gathered together a significant amount of material on Celtic Studies in various countries – Russia, Czechia,2 Bulgaria,3 Serbia,4 Croatia,5 and others – I realised that I could not do the subject justice in the time available 1 I wish to thank my colleague, Dr. Maxim Fomin, for his assistance in the preparation of this paper. 2 Czechia has a long tradition of scholarship relating to Celtic Studies. One of the many influential Irish colleges established on the Continent of Europe, which made important contributions to Irish heritage and scholarship, was located in Prague in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (http://www.irishineurope.com). There have also been many fine Czech linguistic and archaeological scholars. See, for example, the works of the talented Celtic scholar, Josef Baudiš (a bibliography of whose works was compiled by Václav Machek in 1948, available online at http://www.volny.cz/enelen/baud/baud_bib.htm), and other eminent scholars, such as the archaeologists Jan Filip (1956, 1961) and Natalie Venclová (1995, 1998, 2000, 2001), and linguists, such as Václav Machek (1963), Václav Blažek (1999, 2001, 2001a, 2003), and Vera Čapková (1987, 1997). -

Order of Celtic Wolves Lesson 6

ORDER OF CELTIC WOLVES LESSON 6 Introduction Welcome to the sixth lesson. What a fantastic achievement making it so far. If you are enjoying the lessons let like-minded friends know. In this lesson, we are looking at the diet, clothing, and appearance of the Celts. We are also going to look at the complex social structure of the wolves and dispel some common notions about Alpha, Beta and Omega wolves. In the Bards section we look at the tales associated with Lugh. We will look at the role of Vates as healers, the herbal medicinal gardens and some ancient remedies that still work today. Finally, we finish the lesson with an overview of the Brehon Law of the Druids. I hope that there is something in the lesson that appeals to you. Sometimes head knowledge is great for General Knowledge quizzes, but the best way to learn is to get involved. Try some of the ancient remedies, eat some of the recipes, draw principles from the social structure of wolves and Brehon law and you may even want to dress and wear your hair like a Celt. Blessings to you all. Filtiarn Celts The Celtic Diet Athenaeus was an ethnic Greek and seems to have been a native of Naucrautis, Egypt. Although the dates of his birth and death have been lost, he seems to have been active in the late second and early third centuries of the common era. His surviving work The Deipnosophists (Dinner-table Philosophers) is a fifteen-volume text focusing on dining customs and surrounding rituals. -

The Second Heroic Cycle Conference

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Supernatural threats to kings: exploration of a motif in the Ulster Cycle and in other medieval Irish tales Borsje, J. Publication date 2009 Document Version Final published version Published in Ulidia 2: proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Ulster Cycle of Tales, National University of Ireland, Maynooth, 24-27 June 2005 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Borsje, J. (2009). Supernatural threats to kings: exploration of a motif in the Ulster Cycle and in other medieval Irish tales. In R. Ó hUiginn, & B. Ó Catháin (Eds.), Ulidia 2: proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Ulster Cycle of Tales, National University of Ireland, Maynooth, 24-27 June 2005 (pp. 173-194). An Sagart. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Supernatural Threats to Kings: Exploration of a Motif in the Ulster Cycle and in Other Medieval Irish Tales Jacqueline Borsje Introduction he subject of this contribution is the belief in a sacral bond between the land and the ruler. -

Univerzita Karlova V Praze Fakulta Humanitních Studií

Univerzita Karlova v Praze Fakulta humanitních studií OBOR: STUDIUM HUMANITNÍ VZDĚLANOSTI Bakalá řská práce na téma: TROJFUNKČNÍ STRUKTURA V IRSKÉ MYTOLOGII Autorka: Martina Tajbnerová Vedoucí práce: Dr Dalibor Antalík 2006 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci vypracovala samostatn ě s použitím uvedené literatury a souhlasím s jejím eventuálním zve řejn ěním v tišt ěné nebo elektronické podob ě. V Písku dne……. …………………………. 2 OBSAH I.Úvod …………………………………………………………………………………………4 II. Rešerše: a)Idea Indoevropanství…………………………………………………………….6 b)Trojfunk ční struktura u Dumézila ………………………………………………8 c)T ři funkce………………………………………………………………………14 d)Dumézilovy poznatky o trojfunk ční struktu ře u ostrovních Kelt ů………..……20 e)Navazující práce Françoise Le Roux…………………………………………..26 f)Navazující práce Jaana Puhvela………………………………………………..30 III. Samotná práce: a) Keltové………………………………………………………………………..33 b) Nejstarší irské literární památky………………………………………………34 c) T ři poklady Tuatha de Danaan ů a t ři nartské dary…………………………….37 d) Válka funkcí – II. bitva na Mag Tuired?……………………………………...38 e) T ři funkce v mytologii-rozd ělení……………………………………………...41 e1)1.fce-právní a magická:Nuada a Manannan………43 e2)2. fce-vále čná a bojová: Ogma……………………48 e3).3.fce- prosperity a plodnosti: Dagda ……………..50 f)Lug-multifunk ční postava..……………………………………………………..54 IV. Záv ěr……………………………………………………………………………………..57 V.Seznam použité literatury ………………………………………………………………...59 VI. P říloha ……………………………………………………………………………………61 3 I. ÚVOD Tato bakalá řská práce si klade za cíl prokázat trojfunk ční rozd ělení boh ů v keltské mytologii a stru čně popsat jednotlivé funkce (svrchovanost, sílu fyzickou a bojovou a plodnost) a jim p říslušné postavy vystupující v irských mýtech. Celá studie vychází z teorie Georgese Dumézila, která p ředpokládá, že takzvaná trojfunk ční struktura je p řízna čná pouze pro mýty indoevropských národ ů. -

Order of Celtic Wolves Lesson 5

ORDER OF CELTIC WOLVES LESSON 5 Introduction Welcome to the fifth lesson. You are now over a third of your way into the lessons. This lesson has took quite a bit longer than I anticipated to come together. I apologise for this, but whilst putting research together, we want the OCW to be as accurate as possible. One thing that I often struggle with is whether ancient Druids used elements in their rituals. I know modern Druids use elements and directions, and indeed I have used them as part of ritual with my own Grove and witnessed varieties in others. When researching, you do come across different viewpoints and interpretations. All of these are valid, but sometimes it is good to involve other viewpoints. Thus, I am grateful for our Irish expert and interpreter, Sean Twomey, for his input and much of this topic is written by him. We endeavour to cover all the basics in our lessons. However, there will be some topics that interest you more than others. This is natural and when you find something that sparks your interest, then I recommend further study into whatever draws you. No one knows everything, but having an overview is a great starting point in any spiritual journey. That said, I am quite proud of the in-depth topics we have put together, especially on Ogham. You also learn far more from doing exercises than any amount of reading. Head knowledge without application is like having a medical consultation and ignoring specialist advice. In this lesson, we are going to look at Celtic artefacts and symbols, continue with our overview of the Book of Invasions, the magick associated with the Cauldron and how to harness elemental magick. -

CELTIC MYTHOLOGY Ii

i CELTIC MYTHOLOGY ii OTHER TITLES BY PHILIP FREEMAN The World of Saint Patrick iii ✦ CELTIC MYTHOLOGY Tales of Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes PHILIP FREEMAN 1 iv 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America. © Philip Freeman 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress ISBN 978–0–19–046047–1 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America v CONTENTS Introduction: Who Were the Celts? ix Pronunciation Guide xvii 1. The Earliest Celtic Gods 1 2. The Book of Invasions 14 3. The Wooing of Étaín 29 4. Cú Chulainn and the Táin Bó Cuailnge 46 The Discovery of the Táin 47 The Conception of Conchobar 48 The Curse of Macha 50 The Exile of the Sons of Uisliu 52 The Birth of Cú Chulainn 57 The Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn 61 The Wooing of Emer 71 The Death of Aife’s Only Son 75 The Táin Begins 77 Single Combat 82 Cú Chulainn and Ferdia 86 The Final Battle 89 vi vi | Contents 5. -

List of Manuscript and Printed Sources Current Marks and Abreviations

1 1 LIST OF MANUSCRIPT AND PRINTED SOURCES CURRENT MARKS AND ABREVIATIONS * * surrounds insertions by me * * variant forms of the lemmata for finding ** (trailing at end of article) wholly new article inserted by me + + surrounds insertion from the addenda ++ (trailing at end of article) wholly new article inserted from addenda † † marks what is (I believe) certainly wrong !? marks an unidentified source reference [ro] Hogan’s Ro [=reference omitted] {1} etc. different places but within a single entry are thus marked Identical lemmata are numbered. This is merely to separate the lemmata for reference and cross- reference. It does not imply that the lemmata always refer to separate names SOURCES Unidentified sources are listed here and marked in the text (!?). Most are not important but they are nuisance. Identifications please. 23 N 10 Dublin, RIA, 967 olim 23 N 10, antea Betham, 145; vellum and paper; s. xvi (AD 1575); see now R. I. Best (ed), MS. 23 N 10 (formerly Betham 145) in the Library of the RIA, Facsimiles in Collotype of Irish Manuscript, 6 (Dublin 1954) 23 P 3 Dublin, RIA, 1242 olim 23 P 3; s. xv [little excerption] AASS Acta Sanctorum … a Sociis Bollandianis (Antwerp, Paris, & Brussels, 1643—) [Onomasticon volume numbers belong uniquely to the binding of the Jesuits’ copy of AASS in their house in Leeson St, Dublin, and do not appear in the series]; see introduction Ac. unidentified source Acallam (ed. Stokes) Whitley Stokes (ed. & tr.), Acallam na senórach, in Whitley Stokes & Ernst Windisch (ed), Irische Texte, 4th ser., 1 (Leipzig, 1900) [index]; see also Standish H. -

Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race Author: Thomas William Rolleston Release Date: October 16, 2010 [Ebook 34081] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE*** MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE Queen Maev T. W. ROLLESTON MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE CONSTABLE - LONDON [8] British edition published by Constable and Company Limited, London First published 1911 by George G. Harrap & Co., London [9] PREFACE The Past may be forgotten, but it never dies. The elements which in the most remote times have entered into a nation's composition endure through all its history, and help to mould that history, and to stamp the character and genius of the people. The examination, therefore, of these elements, and the recognition, as far as possible, of the part they have actually contributed to the warp and weft of a nation's life, must be a matter of no small interest and importance to those who realise that the present is the child of the past, and the future of the present; who will not regard themselves, their kinsfolk, and their fellow-citizens as mere transitory phantoms, hurrying from darkness into darkness, but who know that, in them, a vast historic stream of national life is passing from its distant and mysterious origin towards a future which is largely conditioned by all the past wanderings of that human stream, but which is also, in no small degree, what they, by their courage, their patriotism, their knowledge, and their understanding, choose to make it.