Tanzania in 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jamhuri Ya Muungano Wa Tanzania Bunge La Tanzania

JAMHURI YA MUUNGANO WA TANZANIA BUNGE LA TANZANIA MKUTANO WA KUMI NA SITA NA KUMI NA SABA YATOKANAYO NA KIKAO CHA KUMI NA NNE (DAILY SUMMARY RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS) 21 NOVEMBA, 2014 MKUTANO WA KUMI NA SITA NA KUMI SABA KIKAO CHA KUMI NA NNE – 21 NOVEMBA, 2014 I. DUA Mwenyekiti wa Bunge Mhe. Mussa Azzan Zungu alisoma Dua saa 3.00 Asubuhi na kuliongoza Bunge. MAKATIBU MEZANI – i. Ndg. Asia Minja ii. Ndg. Joshua Chamwela II. MASWALI: Maswali yafuatayo yaliulizwa na wabunge:- 1. OFISI YA WAZIRI MKUU Swali Na. 161 – Mhe. Betty Eliezer Machangu [KNY: Mhe. Dkt. Cyril Chami] Nyongeza i. Mhe. Betty E. Machangu, mb ii. Mhe. Michael Lekule Laizer, mb iii. Mhe. Prof. Peter Msolla, mb Swali Na. 162 - Mhe. Richard Mganga Ndassa, mb Nyongeza (i) Mhe Richard Mganga Ndassa, mb Swali Na. 163 - Mhe. Anne Kilango Malecela, mb Nyongeza : i. Mhe. Anne Kilango Malecela, mb ii. Mhe. John John Mnyika, mb iii. Mhe. Mariam Nassor Kisangi iv. Mhe. Iddi Mohammed Azzan, mb 2 2. OFISI YA RAIS (UTUMISHI) Swali Na. 164 – Mhe. Ritta Enespher Kabati, mb Nyongeza i. Mhe. Ritta Enespher Kabati, mb ii. Mhe. Vita Rashid Kawawa, mb iii. Mhe. Mch. Reter Msingwa, mb 3. WIZARA YA UJENZI Swali Na. 165 – Mhe. Betty Eliezer Machangu, mb Nyongeza :- i. Mhe. Betty Eliezer Machangu, mb ii. Mhe. Halima James Mdee, mb iii. Mhe. Maryam Salum Msabaha, mb Swali Na. 166 – Mhe. Peter Simon Msingwa [KNY: Mhe. Joseph O. Mbilinyi] Nyongeza :- i. Mhe. Peter Simon Msigwa, Mb ii. Mhe. Assumpter Nshunju Mshama, Mb iii. Mhe. Dkt. Mary Mwanjelwa 4. -

Issued by the Britain-Tanzania Society No 112 Sept - Dec 2015

Tanzanian Affairs Issued by the Britain-Tanzania Society No 112 Sept - Dec 2015 ELECTION EDITION: MAGUFULI vs LOWASSA Profiles of Key Candidates Petroleum Bills Ruaha’s “Missing” Elephants ta112 - final.indd 1 8/25/2015 12:04:37 PM David Brewin: SURPRISING CHANGES ON THE POLITICAL SCENE As the elections approached, during the last two weeks of July and the first two weeks of August 2015, Tanzanians witnessed some very dra- matic changes on the political scene. Some sections of the media were even calling the events “Tanzania’s Tsunami!” President Kikwete addessing the CCM congress in Dodoma What happened? A summary 1. In July as all the political parties were having difficulty in choosing their candidates for the presidency, the ruling Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM) party decided to steal a march on the others by bringing forward their own selection process and forcing the other parties to do the same. 2. It seemed as though almost everyone who is anyone wanted to become president. A total of no less than 42 CCM leaders, an unprec- edented number, registered their desire to be the party’s presidential candidate. They included former prime ministers and ministers and many other prominent CCM officials. 3. Meanwhile, members of the CCM hierarchy were gathering in cover photos: CCM presidential candidate, John Magufuli (left), and CHADEMA / UKAWA candidate, Edward Lowassa (right). ta112 - final.indd 2 8/25/2015 12:04:37 PM Surprising Changes on the Political Scene 3 Dodoma to begin the lengthy and highly competitive selection process. 4. The person who appeared to have the best chance of winning for the CCM was former Prime Minister Edward Lowassa MP, who was popular in the party and had been campaigning hard. -

Zanzibar Human Rights Report 2015 by Zlsc

Zanzibar Human Rights Report 2015 TransformIfanye Justicehaki IweInto shaukuPassion Zanzibar Legal Services Centre i Funded by: Embassy of Sweden, Embassy of Finland The Embassy of Norway, Ford Foundation, and Open Society Initiatives for Eastern Africa, Publisher Zanzibar Legal Services Centre P.O.Box 3360,Zanzibar Tanzania Tel:+25524 2452936 Fax:+255 24 2334495 E-mail: [email protected] Website:www.zlsc.or.tz ZLSC May 2016 ii ZANZIBAR HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT 2015 Editorial Board Prof. Chris Maina Peter Mrs. Josefrieda Pereira Ms. Salma Haji Saadat Mr. Daudi Othman Kondo Ms. Harusi Miraji Mpatani Writers Dr. Moh’d Makame Mr. Mzee Mustafa Zanzibar Legal Services Centre @ ZLSC 2015 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Zanzibar Legal Services Centre is indebted to a number of individuals for the support and cooperation during collection, compilation and writing of the 10th Human Rights Report (Zanzibar Chapter). The contribution received makes this report a worthy and authoritative document in academic institutions, judiciary, government ministries and other departments, legislature and educative material to general public at large. The preparation involved several stages and in every stage different stakeholders were involved. The ZLSC appreciate the readiness and eager motive to fill in human rights opinion survey questionnaires. The information received was quite useful in grasping grassroots information relevant to this report. ZLSC extend their gratitude to it’s all Programme officers especially Adv. Thabit Abdulla Juma and Adv. Saida Amour Abdallah who worked hard on completion of this report. Further positive criticism and collections made by editorial board of the report are highly appreciated and valued. Without their value contributions this report would have jeopardised its quality and relevance to the general public. -

Tanzanian State

THE PRICE WE PAY TARGETED FOR DISSENT BY THE TANZANIAN STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2019 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: © Amnesty International (Illustration: Victor Ndula) (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2019 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 56/0301/2019 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 METHODOLOGY 8 1. BACKGROUND 9 2. REPRESSION OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND INFORMATION 11 2.1 REPRESSIVE MEDIA LAW 11 2.2 FAILURE TO IMPLEMENT EAST AFRICAN COURT OF JUSTICE RULINGS 17 2.3 CURBING ONLINE EXPRESSION, CRIMINALIZATION AND ARBITRARY REGULATION 18 2.3.1 ENFORCEMENT OF THE CYBERCRIMES ACT 20 2.3.2 REGULATING BLOGGING 21 2.3.3 CYBERCAFÉ SURVEILLANCE 22 3. EXCESSIVE INTERFERENCE WITH FACT-CHECKING OFFICIAL STATISTICS 25 4. -

The Authoritarian Turn in Tanzania

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery The Authoritarian Turn in Tanzania Dan Paget is a PhD candidate at the University of Oxford, where he is writing his thesis on election campaigning in sub-Saharan Africa, and in particular the uses of the rally. While living in Tanzania in 2015, he witnessed the general election campaign and the beginning of Magufuli’s presidency first-hand. Abstract Since 2015, Tanzania has taken a severe authoritarian turn, accompanied by rising civil disobedience. In the process, it has become a focal point in debates about development and dictatorship. This article unpicks what is happening in contemporary Tanzania. It contends that Tanzania is beset by a struggle over its democratic institutions, which is rooted in rising party system competition. However, this struggle is altered by past experience in Zanzibar. The lessons that both government and opposition have drawn from Zanzibar make the struggle in mainland Tanzania more authoritarian still. These dynamics amount to a new party system trajectory in Tanzania Dan Paget 2 The Tanzanian general election of 2015 seemed like a moment of great democratic promise. Opposition parties formed a pre-electoral coalition, which held. They were joined by a string of high-profile defectors from the ruling CCM (Chama cha Mapinduzi, or the Party of the Revolution). The defector-in-chief, Edward Lowassa, became the opposition coalition’s presidential candidate and he won 40 per cent of the vote, the strongest showing that an opposition candidate has ever achieved in Tanzania. -

Check Against Delivery HOTUBA YA WAZIRI MKUU, MHESHIMIWA

Check Against Delivery HOTUBA YA WAZIRI MKUU, MHESHIMIWA EDWARD LOWASSA, (MB), WAKATI WA KUTOA HOJA YA KUAHIRISHA MKUTANO WA SITA WA BUNGE LA JAMHURI YA MUUNGANO WA TANZANIA, DODOMA, TAREHE 9 FEBRUARI, 2007 Mheshimiwa Spika, Mkutano wa sita wa Bunge lako Tukufu umehitimisha shughuli zote zilizokuwa zimepangwa. Mkutano huu ni wa kwanza baada ya Serikali ya Awamu ya Nne kutimiza mwaka mmoja madarakani. Taarifa za mafanikio na changamoto zilizojitokeza zimewasilishwa kupitia mikutano mbalimbali ya Chama Tawala, Serikali na vyombo mbalimbali vya habari. Mheshimiwa Spika, kwa masikitiko makubwa, nachukua nafasi hii tena kwa niaba ya Serikali na wafanyakazi wa Ofisi ya Waziri Mkuu kutoa rambirambi kwako wewe Mheshimiwa Spika, kwa Waheshimiwa Wabunge wote, kwa familia, jamaa na marafiki kwa msiba uliotokana na kifo cha aliyekuwa Mbunge wa Tunduru, na Waziri wa Nchi, Ofisi ya Waziri Mkuu, (Bunge na Uratibu) Marehemu Juma Jamaldin Akukweti. Wote tulimfahamu Marehemu Akukweti kwa umakini na umahiri wake hapa Bungeni. Marehemu Akukweti alifariki kutokana na ajali ya ndege iliyokuwa inamrejesha Dar es Salaam baada ya kumaliza kazi ya kukagua soko la Mwanjelwa lililoteketea kwa moto mkoani Mbeya. Katika ajali hiyo Watumishi wa Serikali walipoteza maisha. Watumishi hao ni Bibi Theresia Nyantori, Mwandishi wa Habari wa Idara ya Habari; Bwana Nathaniel Katinila, Mratibu wa Mradi wa Masoko; na Bwana George Bendera, Afisa Habari Idara ya Maafa, Ofisi ya Waziri Mkuu. Majeruhi katika ajali hiyo ambao bado wanapata matibabu lakini wametoka hosptali ni Bw. Nisetas Kanje, Katibu wa Waziri wa Nchi, Ofisi ya Waziri Mkuu, (Bunge na Uratibu); na rubani wa ndege hiyo Bw. Martin Sumari. Tunamwomba Mwenyezi Mungu awasaidie majeruhi wote waweze kupona haraka na kurudia katika afya zao. -

Tanzania Human Rights Report 2008

Legal and Human Rights Centre Tanzania Human Rights Report 2008: Progress through Human Rights Funded By; Embassy of Finland Embassy of Norway Embassy of Sweden Ford Foundation Oxfam-Novib Trocaire Foundation for Civil Society i Tanzania Human Rights Report 2008 Editorial Board Francis Kiwanga (Adv.) Helen Kijo-Bisimba Prof. Chris Maina Peter Richard Shilamba Harold Sungusia Rodrick Maro Felista Mauya Researchers Godfrey Mpandikizi Stephen Axwesso Laetitia Petro Writers Clarence Kipobota Sarah Louw Publisher Legal and Human Rights Centre LHRC, April 2009 ISBN: 978-9987-432-74-5 ii Acknowledgements We would like to recognize the immense contribution of several individuals, institutions, governmental departments, and non-governmental organisations. The information they provided to us was invaluable to the preparation of this report. We are also grateful for the great work done by LHRC employees Laetitia Petro, Richard Shilamba, Godfrey Mpandikizi, Stephen Axwesso, Mashauri Jeremiah, Ally Mwashongo, Abuu Adballah and Charles Luther who facilitated the distribution, collection and analysis of information gathered from different areas of Tanzania. Our 131 field human rights monitors and paralegals also played an important role in preparing this report by providing us with current information about the human rights’ situation at the grass roots’ level. We greatly appreciate the assistance we received from the members of the editorial board, who are: Helen Kijo-Bisimba, Francis Kiwanga, Rodrick Maro, Felista Mauya, Professor Chris Maina Peter, and Harold Sungusia for their invaluable input on the content and form of this report. Their contributions helped us to create a better report. We would like to recognize the financial support we received from various partners to prepare and publish this report. -

Majadiliano Ya Bunge ______

Hii ni Nakala ya Mtandao (Online Document) BUNGE LA TANZANIA ___________ MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE ___________ MKUTANO WA NANE Kikao cha Thelathini na Tisa – Tarehe 2 AGOSTI, 2012 (Mkutano Ulianza Saa Tatu Asubuhi) DUA Spika (Mhe. Anne S. Makinda) Alisoma Dua HATI ZILIZOWASILISHWA MEZANI Hati ifuatayo iliwasilishwa Mezani na:- NAIBU WAZIRI WA USHIRIKIANO WA AFRIKA MASHARIKI: Randama za Makadirio ya Mapato na Matumizi ya Wizara ya Ushirikiano wa Afrika Mashariki kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2012/2013. SPIKA: Waheshimiwa Wabunge, naomba mzime vipasa sauti vyenu maana naona vinaingiliana. Ahsante Mheshimiwa Naibu Waziri, tunaingia hatua inayofuata. MASWALI NA MAJIBU SPIKA: Leo ni siku ya Alhamisi lakini tulishatoa taarifa kwamba Waziri Mkuu yuko safarini kwa hiyo kama kawaida hatutakuwa na kipindi cha maswali hayo. Maswali ya kawaida yapo machache na atakayeuliza swali la kwanza ni Mheshimiwa Vita R. M. Kawawa. Na. 310 Fedha za Uendeshaji Shule za Msingi MHE. VITA R. M. KAWAWA aliuliza:- Kumekuwa na makato ya fedha za uendeshaji wa Shule za Msingi - Capitation bila taarifa hali inayofanya Walimu kuwa na hali ngumu ya uendeshaji wa shule hizo. Je, Serikali ina mipango gani ya kuhakikisha kuwa, fedha za Capitation zinatoloewa kama ilivyotarajiwa ili kupunguza matatizo wanayopata wazazi wa wanafunzi kwa kuchangia gharama za uendeshaji shule? NAIBU WAZIRI, OFISI YA WAZIRI MKUU, TAWALA ZA MIKOA NA SERIKALI ZA MITAA (ELIMU) alijibu:- Mheshimiwa Spika, kwa niaba ya Mheshimiwa Waziri Mkuu, naomba kujibu swali la Mheshimiwa Vita Rashid Kawawa, Mbunge wa Namtumbo, kama ifuatavyo:- Mheshimiwa Spika, Serikali kupitia Mpango wa Maendeleo ya Elimu ya Msingi (MMEM) imepanga kila mwanafunzi wa Shule ya Msingi kupata shilingi 10,000 kama fedha za uendeshaji wa shule (Capitation Grant) kwa mwaka. -

Hii Ni Nakala Ya Mtandao (Online Document)

Hii ni Nakala ya Mtandao (Online Document) MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE _____________ MKUTANO WA KUMI NA SITA ______________ Kikao cha Thelathini na Tisa – Tarehe 27 Julai, 2009) (Kikao Kilianza Saa Tatu Asubuhi) DUA Spika (Mhe. Samuel J. Sitta) Alisoma Dua MASWALI NA MAJIBU SPIKA: Waheshimiwa Wabunge, kabla sijamwita anayeuliza swali la kwanza, karibuni tena baada ya mapumziko ya weekend, nadhani mna nguvu ya kutosha kwa ajili ya shughuli za wiki hii ya mwisho ya Bunge hili la 16. Swali la kwanza linaelekezwa Ofisi ya Waziri Mkuu na linauliza na Mheshimiwa Shoka, kwa niaba yake Mheshimiwa Khalifa. Na.281 Kiwanja kwa Ajili ya Kujenga Ofisi ya Tume ya Kudhibiti UKIMWI MHE KHALIFA SULEIMAN KHALIFA (K.n.y. MHE. SHOKA KHAMIS JUMA) aliuliza:- Kwa kuwa Tume ya Taifa ya Kudhibiti UKIMWI inakabiliwa na changamoto ya ufinyu wa Ofisi; na kwa kuwa Tume hiyo imepata fedha kutoka DANIDA kwa ajili ya kujenga jengo la Ofisi lakini inakabiliwa na tatizo kubwa la upatikanaji wa kiwanja:- Je, Serikali itasaidia vipi Tume hiyo kupata kiwanja cha kujenga Ofisi? WAZIRI WA NCHI, OFISI YA WAZIRI MKUU – SERA, URATIBU NA BUNGE alijibu:- Mheshimiwa Spika, kwa niaba ya Mheshimiwa Waziri Mkuu, napenda kujibu swali la Mheshimiwa Shoka Khamis Juma, Mbunge wa Micheweni kama ifuatavyo:- Mheshimiwa Spika, tatizo la kiwanja cha kujenga Ofisi za TACAIDS limepatiwa ufumbuzi na ofisi yangu imewaonesha Maafisa wa DANIDA kiwanja hicho Ijumaa tarehe 17 Julai, 2009. Kiwanja hicho kipo Mtaa wa Luthuli Na. 73, Dar es Salaam ama kwa lugha nyingine Makutano ya Mtaa wa Samora na Luthuli. MHE. KHALIFA SULEIMAN KHALIFA: Mheshimiwa Spika, nakushukuru. Pamoja na majibu mazuri sana ya Mheshimiwa Waziri, naomba kumuuliza swali moja la nyongeza. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Accountability and Clientelism in Dominant Party Politics: The Case of a Constituency Development Fund in Tanzania Machiko Tsubura Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Development Studies University of Sussex January 2014 - ii - I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature: ……………………………………… - iii - UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX MACHIKO TSUBURA DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES ACCOUNTABILITY AND CLIENTELISM IN DOMINANT PARTY POLITICS: THE CASE OF A CONSTITUENCY DEVELOPMENT FUND IN TANZANIA SUMMARY This thesis examines the shifting nature of accountability and clientelism in dominant party politics in Tanzania through the analysis of the introduction of a Constituency Development Fund (CDF) in 2009. A CDF is a distinctive mechanism that channels a specific portion of the government budget to the constituencies of Members of Parliament (MPs) to finance local small-scale development projects which are primarily selected by MPs. -

Hii Ni Nakala Ya Mtandao (Online Document)

Hii ni Nakala ya Mtandao (Online Document) BUNGE LA TANZANIA ____________ MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE ___________ MKUTANO WA NNE Kikao cha Ishirini na Nne – Tarehe 18 Julai, 2006 (Mkutano Ulianza Saa Tatu Asubuhi) D U A Spika (Mhe. Samuel J. Sitta) Alisoma Dua MASWALI NA MAJIBU SPIKA: Waheshimiwa Wabunge, kabla sijamwita muuliza swali la kwanza nina matangazo kuhusu wageni, kwanza wale vijana wanafunzi kutoka shule ya sekondari, naona tangazo halisomeki vizuri, naomba tu wanafunzi na walimu msimame ili Waheshimiwa Wabunge waweze kuwatambua. Tunafurahi sana walimu na wanafunzi wa shule zetu za hapa nchini Tanzania mnapokuja hapa Bungeni kujionea wenyewe demokrasia ya nchi yetu inavyofanya kazi. Karibuni sana. Wapo Makatibu 26 wa UWT, ambao wamekuja kwenye Semina ya Utetezi na Ushawishi kwa Harakati za Wanawake inayofanyika Dodoma CCT wale pale mkono wangu wakulia karibuni sana kina mama tunawatakia mema katika semina yenu, ili ilete mafanikio na ipige hatua mbele katika kumkomboa mwanamke wa Tanzania, ahsanteni sana. Hawa ni wageni ambao tumetaarifiwa na Mheshimiwa Shamsa Selengia Mwangunga, Naibu Waziri wa Maji. Wageni wengine nitawatamka kadri nitakavyopata taarifa, kwa sababu wamechelewa kuleta taarifa. Na. 223 Barabara Toka KIA – Mererani MHE. DORA H. MUSHI aliuliza:- Kwa kuwa, Mererani ni Controlled Area na ipo kwenye mpango wa Special Economic Zone na kwa kuwa Tanzanite ni madini pekee duniani yanayochimbwa huko Mererani na inajulikana kote ulimwenguni kutokana na madini hayo, lakini barabara inayotoka KIA kwenda Mererani ni mbaya sana -

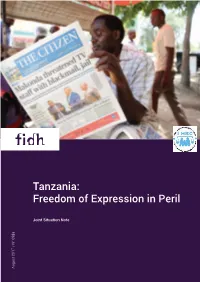

Tanzania: Freedom of Expression in Peril

Tanzania: Freedom of Expression in Peril Joint Situation Note August 2017 / N° 698a August Cover photo: A man reads on March 23, 2017 in Arusha, northern Tanzania, the local English-written daily newspaper «The Citizen», whose front title refers to the sacking of Tanzanian information Minister after he criticised an ally of the president. Tanzania’s President, aka «The Bulldozer» sacked his Minister for Information, Culture and Sports, after he criticised an ally of the president: the Dar es Salaam Regional Commissioner who had stormed into a television station accompanied by armed men. © STRINGER / AFP FIDH and LHRC Joint Situation Note – August 1, 2017 - 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction..........................................................................................................................2 I. Dissenting voices have become targets of the authorities..........................................5 II. Human Rights Defenders and ordinary citizens are also in the sights of the authorities...........................................................................................................................10 Recommendations.............................................................................................................12 Annex I – Analysis: Tools for repression: the Media Services Act and the Cybercrimes Act.................................................................................................................13 Annex II – List of journalists and human rights defenders harassed..........................17