Induced Sputum Inflammatory Measures Correlate with Disease Severity in Children with Obstructive Sleep Apnoea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

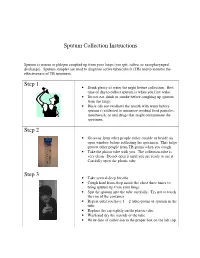

Sputum Collection Instructions Step 1 Step 2 Step 3

Sputum Collection Instructions Sputum is mucus or phlegm coughed up from your lungs (not spit, saliva, or nasopharyngeal discharge). Sputum samples are used to diagnose active tuberculosis (TB) and to monitor the effectiveness of TB treatment. Step 1 • Drink plenty of water the night before collection. Best time of day to collect sputum is when you first wake. • Do not eat, drink or smoke before coughing up sputum from the lungs. • Rinse (do not swallow) the mouth with water before sputum is collected to minimize residual food particles, mouthwash, or oral drugs that might contaminate the specimen. Step 2 • Go away from other people either outside or beside an open window before collecting the specimen. This helps protect other people from TB germs when you cough. • Take the plastic tube with you. The collection tube is very clean. Do not open it until you are ready to use it. Carefully open the plastic tube. Step 3 • Take several deep breaths. • Cough hard from deep inside the chest three times to bring sputum up from your lungs. • Spit the sputum into the tube carefully. Try not to touch the rim of the container. • Repeat until you have 1 – 2 tablespoons of sputum in the tube. • Replace the cap tightly on the plastic tube. • Wash and dry the outside of the tube. • Write date of collection in the proper box on the lab slip. Step 4 • Place the primary specimen container (usually a conical centrifuge tube) in the clear plastic baggie that has the biohazard symbol imprint. • Place the white absorbent sheet in the plastic baggie. -

Perinatal/Neonatal Case Presentation

Perinatal/Neonatal Case Presentation &&&&&&&&&&&&&& Urinary Tract Infection With Trichomonas vaginalis in a Premature Newborn Infant and the Development of Chronic Lung Disease David J. Hoffman, MD vaginal bleeding with suspected abruption resulted in delivery of Gerard D. Brown, DO the infant by Cesarean section. The Apgar scores were 1, 5, and 9 Frederick H. Wirth, MD at 1, 5, and 10 minutes of life, respectively. Betsy S. Gebert, CRNP After delivery, the infant was managed with mechanical Cathy L. Bailey, MS, CRNP ventilation with pressure support and volume guarantee for Endla K. Anday, MD respiratory distress syndrome. She received exogenous surfactant We report a case of a low-birth-weight infant with an infection of the urinary tract with Trichomonas vaginalis, who later developed cystic chronic lung disease suggestive of Wilson-Mikity syndrome. Although she had mild respiratory distress syndrome at birth, the extent of the chronic lung disease was out of proportion to the initial illness. We speculate that maternal infection with this organism may have resulted in an inflammatory response that led to its development. Journal of Perinatology (2003) 23, 59 – 61 doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7210819 CASE PRESENTATION A 956-g, appropriate-for-gestational-age, African–American female was delivered by Cesarean section following 27 5/7 weeks of gestation in breech presentation after a period of advanced cervical dilatation and uterine contractions. Her mother was a 20-year-old gravida 5, para 2022 woman whose prenatal laboratory data were significant for vaginal colonization with Streptococcus agalactiae, treatment for Chlamydia trachomatis, and a history of cocaine and marijuana usage confirmed by urine toxicology. -

Chest Pain in Pediatrics

PEDIATRIC CARDIOLOGY 0031-3955/99 $8.00 + .OO CHEST PAIN IN PEDIATRICS Keith C. Kocis, MD, MS Chest pain is an alarming complaint in children, leading an often frightened and concerned family to a pediatrician or emergency room and commonly to a subsequent referral to a pediatric cardiologist. Because of the well-known associ- ation of chest pain with significant cardiovascular disease and sudden death in adult patients, medical personnel commonly share heightened concerns over pediatric patients presenting with chest pain. Although the differential diagnosis of chest pain is exhaustive, chest pain in children is least likely to be cardiac in origin. Organ systems responsible for causing chest pain in children include*: Idiopathic (12%-85%) Musculoskeletal (15%-31%) Pulmonary (12%-21%) Other (4%-21%) Psychiatric (5%-17%) Gastrointestinal (4'/0-7%) Cardiac (4%4%) Furthermore, chest pain in the pediatric population is rareZy associated with life-threatening disease; however, when present, prompt recognition, diagnostic evaluation, and intervention are necessary to prevent an adverse outcome. This article presents a comprehensive list of differential diagnostic possibilities of chest pain in pediatric patients, discusses the common causes in further detail, and outlines a rational diagnostic evaluation and treatment plan. Chest pain, a common complaint of pediatric patients, is often idiopathic in etiology and commonly chronic in nature. In one study,67 chest pain accounted for 6 in 1000 visits to an urban pediatric emergency room. In addition, chest pain is the second most common reason for referral to pediatric cardiologist^.^, 23, 78 Chest pain is found equally in male and female patients, with an average *References 13, 17, 23, 27, 32, 35, 44, 48, 49, 63-67, 74, and 78. -

Evaluation of Upper Airway Changes Following Surgical Removal of the Adenoids Using 3-D Cone Beam CT

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC Theses & Dissertations Graduate Studies Fall 12-18-2015 Evaluation of Upper Airway Changes Following Surgical Removal of the Adenoids Using 3-D Cone Beam CT Christopher C. Schultz University of Nebraska Medical Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/etd Part of the Other Medical Specialties Commons Recommended Citation Schultz, Christopher C., "Evaluation of Upper Airway Changes Following Surgical Removal of the Adenoids Using 3-D Cone Beam CT" (2015). Theses & Dissertations. 54. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/etd/54 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVALUATION OF UPPER AIRWAY CHANGES FOLLOWING SURGICAL REMOVAL OF THE ADENOIDS USING 3-D CONE BEAM CT By Christopher C. Schultz, D.D.S A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College in the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Medical Sciences Interdepartmental Area Oral Biology University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, Nebraska December, 2015 Advisory Committee: Sundaralingam Premaraj, BDS, MS, PhD, FRCD(C) Sheela Premaraj, BDS, PhD Peter J. Giannini, DDS, MS Stanton D. Harn, PhD i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my thanks and gratitude to the members of my thesis committee: Dr. Sundaralingam Premaraj, Dr. Sheela Premaraj, Dr. Peter Giannini, and Dr. Stanton Harn. Your advice and assistance has been vital for the completion of the project. -

What Is Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome?

American Thoracic Society PATIENT EDUCATION | INFORMATION SERIES What is Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome? Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) is a life-threatening illness in which the lungs are severely inflamed. Swelling throughout the lungs cause tiny blood vessels to leak fluid and the air sacs (alveoli) collapse or fill with fluid, preventing the lungs from working well. Patients with ARDS have problems getting enough oxygen into their blood so they must be given extra oxygen and will usually need a ventilator to breathe. Despite intensive treatment, about 40% of people with ARDS die from lung failure. Who gets ARDS? How is ARDS treated? It is estimated that ARDS affects about 150,000 Currently, there is no specific treatment for ARDS. Americans each year. ARDS can occur in many situations. Treatment consists of two goals: ARDS can affect people who have known lung disease or ■ treat any medical problem that led to the lung injury, other serious illnesses. A person can develop ARDS even and if he or she has not had lung disease or a lung problem in ■ support the person’s breathing (usually with a the past. ventilator) until the lungs heal. Most people with ARDS What causes ARDS? are treated in the hospital’s intensive care unit (ICU). The causes of ARDS are not well understood. Either Therapies commonly used for ARDS include: direct or indirect injuries can cause ARDS. Direct ■ Breathing support from a mechanical ventilator. injuries include: pneumonia, inhaling stomach contents ■ CLIP AND COPY AND CLIP Medicines to keep the person calm and comfortable (aspiration), breathing in harmful fumes or smoke, and while on the ventilator so that they can rest and injury to the chest that causes bruising of the lungs. -

What Is Acute Bronchitis?

What is acute bronchitis? FACT SHEET prepared by The Asthma and Respiratory Foundation NZ Acute bronchitis is an infection of the large bronchi (airways) in the lungs. The airways swell and thick mucus builds up inside them. It is often caused by the same viruses that cause the common cold. A minority of cases are caused by bacteria. How do I know that I have acute bronchitis? Acute bronchitis may accompany or closely follow a cold or influenza or may occur on its own. The major symptom of acute bronchitis is a productive cough that may bring up yellow or green sputum (phlegm). This cough can last several weeks. Some people may have shortness of breath and a wheeze. There may be other symptoms associated with the viral cause such as a runny nose, sore throat, fever, muscle aches and pains, sore eyes or headache, particularly early in the illness. Chest pain is not usually associated with bronchitis. Who gets acute bronchitis? Anyone can get acute bronchitis. It is more common in winter, especially during influenza outbreaks. Tobacco smoke and other air pollutants appear to worsen symptoms and may prolong the cough. People with a chronic lung disease can also get acute bronchitis, but may need different treatment. How is acute bronchitis treated? Most cases will go away after a few days or a week though the cough may linger for several weeks or months. This indicates that the airways are taking a longer time to heal. As most cases of acute bronchitis are caused by virus’s, antibiotics are usually not effective. -

Plastic Bronchitis by R

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.15.4.325 on 1 December 1960. Downloaded from Thorax (1960), 15, 325. PLASTIC BRONCHITIS BY R. SLEIGH JOHNSON AND E. G. SITA-LUMSDEN From Southend-on-Sea Hospital, Essex (RECEIVED FOR PUBLICATION MAY 18, 1960) The specific feature of plastic bronchitis is the She remained free from serious attacks until May, formation of obstructive bronchial plugs or casts 1954, when after moving house a coryzal attack of thick, tenacious mucus during an attack of developed into acute bronchitis with asthma. She had severe, stabbing pain in the centre of the back and bronchitis, when one or more lobes or even an lower chest mainly on the left, induced by movement, entire lung may collapse. Casts are often expec- coughing, or breathing. Dyspnoea was so severe that torated, but they may be discovered only at even speaking caused distress, and she became very ill bronchoscopy, or be found lying in the bronchial with fever, sweating, cough, and creamy sputum. tree at necropsy. They consist largely of mucus, Admitted as an emergency, she had an immobile, silent and may also contain fibrin, pus cells, and blood, left lung, and the heart and mediastinum were as well as elements commonly found in asthmatic displaced to the left (Fig. 1). attacks such as eosinophil cells, Charcot-Leyden As she did not improve, bronchoscopy was carried crystals, and Curshmann's spirals. out: the left stem bronchus was completely obstructed by a plug of tough, inspissated mucus which appeared to be lightly adherent to the bronchial wall but proved CASE REPORTS too viscid to be dislodged by aspiration alone. -

Assessment of Cough Cough Remains One of the Most Common Complaints That Motivate Patients to Seek Medical Attention

Assessment of cough Cough remains one of the most common complaints that motivate patients to seek medical attention. GILLIAN AINSLIE, MB ChB, FRCP (Lond) UCT Lung Institute and Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town Gillian Ainslie is a specialist pulmonologist at Groote Schuur Hospital and the University of Cape Town. She is a past president of both the South African Thoracic Society and the National Asthma Education Programme (where she developed the South African Diploma of Asthma). Her main interest is interstitial lung disease. Cough is caused by stimulation of irritant receptors in the central airways and/or stretch receptors in the distal airways or the lung Smokers who cough usually interstitium. It is a normal protective mechanism, which may be feel that their cough is due lost with local or general anaesthesia, other causes of decreased level of consciousness, or neuromuscular problems (especially bulbar). to smoking and therefore Cough is abnormal if it is persistent, painful or productive. rarely seek medical advice specifically for it. His tory and examination If a patient presents with a cough, the following features should be clarified on history: Chronic cough • duration – days, weeks, months or years Chronic cough as the only symptom can account for up to 10% of all referrals to general respiratory clinics1 and occurs in 3 - 40% • course – constant, worsening, intermittent, diurnal variation of the general population.2 Unsurprisingly, cigarette smoking has • triggers – allergens, irritants, swallowing, position a dose-related influence on the prevalence of productive cough.2 • dry or productive (nature and volume of sputum) – clear/ Smokers who cough usually feel that their cough is due to smoking white/grey (mucoid), yellow/green (purulent) or bloody and therefore rarely seek medical advice specifically for it. -

Many Faces of Chest Pain Ian Mcleod, MS, Med, PA-C, ATC Northern Arizona University ASAPA Spring Conference 2019 Disclosures

Many Faces of Chest Pain Ian McLeod, MS, MEd, PA-C, ATC Northern Arizona University ASAPA Spring Conference 2019 Disclosures • I have no financial disclosures to report Objectives • Following the presentation attendees will be able to: • Develop a concise differential diagnosis for patients with chest pain including cardiac and non-cardiac causes. • Describe key clinical characteristics and management of the following chest pain etiologies: angina, embolism, gastroesophageal reflux, costochondritis, costochondral dysfunction, anxiety and pneumonia. • Discuss appropriate use of diagnostic studies utilized in the evaluation of patients presenting with chest pain. Chest Pain – Primary Care Setting • ~1.5% of all visits are for chest pain • Musculoskeletal 35-50% • Gastrointestinal 10-20% • Cardiac 10-15% • Pulmonary 5-10% • Psychogenic 1-2% Chest Pain Differentials • Cardiac • Pulmonary • Stable angina • Pneumonia • Acute coronary syndrome • Pulmonary embolism • Pericarditis • Spontaneous pneumothorax • Aortic dissection • Psych • MSK • Panic disorder • Costochondritis • Tietze syndrome • Costovertebral joint dysfunction • GI • Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) • Medication induced esophagitis Setting the stage • Non-traumatic • Acute chest pain • Primary care setting • H&P • ECG • CXR Myocardial Ischemia Risk Factors • Increasing age • Male sex • Chronic renal insufficiency • Diabetes Mellitus • Known atherosclerotic disease → coronary or peripheral • Early family history of coronary artery disease • 1st degree male relative < 55 y/o -

How to Collect a Sputum Sample for Your Lab Test

How to Collect a Sputum Sample for Your Lab Test General Information Rinse or gargle with water. Your health care provider has ordered a sputum Collecting Your Sputum Sample (also called mucus or phlegm) collection test. The test that is circled below is the one you will Collect only one sample per day. need to do. Collect the sample(s) right away when you wake up from sleeping. Cough as deeply Before Collecting Your as possible to raise the sputum from your Sputum Sample lungs (instead of saliva from your mouth). You will be given the collection container(s) If you have problems collecting your for your lab test before you are sent home. sample, call your health care provider. Write the following information on each of Follow the directions below to complete your collection containers: your sputum collection test. — your full name — date of collection — time of collection. Test Container Directions Sputum Culture, Stain clean cup with Collect one sample. a screw cap For best results, return the sample to the clinic within two hours. If this is not possible, keep the sample at room temperature and return it within 24 hours. AFB Culture, Stain clean cup with Collect a total of three samples on separate days. a screw cap Collect each sample in a different cup. Keep the samples in the refrigerator. Return all of the samples to the clinic at one time. Fungus Culture clean cup with Collect a total of three samples on separate days. a screw cap Collect each sample in a different cup. Keep the samples in the refrigerator. -

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS of HEMOPTYSIS. by W

56 POST-GRADUATE MEDICAL JOURNAL February, 1938 Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.14.148.56 on 1 February 1938. Downloaded from THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF HEMOPTYSIS. By W. ERNEST LLOYD, M.D., F.R.C.P. (Assistant Physician, Westminster Hospital and Brompton Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest.) Haemoptysis or blood-spitting is a symptom of many different diseases and it should always lead to a complete investigation of the patient so as to try and determine its cause. The amount of blood expectorated varies greatly from a few streaks of blood in the phlegm or blood-stained sputum to a free hemorrhage of many ounces. When it occurs for the first time it is rarely copious but it is a symptom which always causes great anxiety and rarely does a patient ignore it. This is in striking contrast to other symptoms of chest disease for a patient may have had a cough for months before seeking medical advice. When a patient goes to a doctor with the history of having coughed up blood, a re-assuring attitude should be adopted and a history of the circumstances accompanying the haemoptysis should be obtained. If possible, the actual blood should be observed especially if the history is not clear whether the blood was actually coughed up or vomited. Occasionally, a history of epistaxis precedes that of the haemoptysis and blood may be seen to be coming from the naso- pharynx. Protected by copyright. The past history of the patient may offer a clue to the vetiology. -

Dolore.Toracico.Zuliani

CHEST PAIN Prof. Giovanni Zuliani CHEST PAIN • Chest pain accounts for about 4-5% of all Emergency Department visits per year in Western Countries (chest pain units) • The differential diagnosis of chest pain is really important and extensive in Internal Medicine CHEST PAIN 1. ANATOMY OF THORAX 2. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS 3. OVERVIEW OF DISEASES AND PROCESSES CAUSING CHEST PAIN 4. APPROACH TO CHEST PAIN CHEST ANATOMY SKIN MUSCLES CHEST ANATOMY BONES CHEST ANATOMY PULMONARY SYSTEM CHEST ANATOMY HEART CHEST ANATOMY VASCULATURE AND GI SYSTEM AORTA AND ESOPHAGUS DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF CHEST PAIN 1) CHEST WALL PAIN 2) PULMONARY CAUSES 3) CARDIAC CAUSES 4) VASCULAR CAUSES 5) G.I. CAUSES 6) OTHER (PSYCHOGENIC CAUSES) 1. CHEST WALL PAIN . DDX: CHEST PAIN • CHEST WALL PAIN - Skin and sensory nerves: - Herpes Zoster - Musculoskeletal system: - Isolated Musculoskeletal Chest Pain Syndrome: * Costochondritis * Xiphoidalgia * Precordial Catch Syndrome * Rib Fractures - Rheumatic and Systemic Diseases causing chest wall pain CHEST WALL PAIN • HERPES ZOSTER - Reactivation of Herpes Varicellae virus - Immuno-compromised patients (HIV, stress, very old / fragile subjects) are often at risk for reactivation. - 60% of zoster infections involve the trunk - Pain often precede rash (very rarely pain without rash) HERPES ZOSTER • Clusters of vesicles (with clear or purulent fluid) grouped on an erythematous base. Lesions eventually rupture and crust. • Dermatomal distribution. • Usually unilateral involvement that halts at midline. Herpes Zoster H. ZOSTER: TREATMENT • ZOSTER VIRUS: * Antivirals: Acyclovir (800 mg x4/day) or Valacyclovir (1g/8h) reduce duration of symptoms. Might also reduce incidence of post-herpetic neuralgia. * +/- Corticosteroids: may reduce inflammation * Analgesia: NSAIDS, Paracetamol, Tramadol POSTHERPETIC NEURALGIA: * May follow the course of acute zoster: shooting, sharp pain, hyperesthesia in involved dermatome * Treatment: Analgesics (NSAIDS, Opioids), Antiepileptics (Carbamazepine, Fenitoin, Gabapentin), Antidepressants (e.g.