Pneumonia Panel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Captive Orcas

Captive Orcas ‘Dying to Entertain You’ The Full Story A report for Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society (WDCS) Chippenham, UK Produced by Vanessa Williams Contents Introduction Section 1 The showbiz orca Section 2 Life in the wild FINgerprinting techniques. Community living. Social behaviour. Intelligence. Communication. Orca studies in other parts of the world. Fact file. Latest news on northern/southern residents. Section 3 The world orca trade Capture sites and methods. Legislation. Holding areas [USA/Canada /Iceland/Japan]. Effects of capture upon remaining animals. Potential future capture sites. Transport from the wild. Transport from tank to tank. “Orca laundering”. Breeding loan. Special deals. Section 4 Life in the tank Standards and regulations for captive display [USA/Canada/UK/Japan]. Conditions in captivity: Pool size. Pool design and water quality. Feeding. Acoustics and ambient noise. Social composition and companionship. Solitary confinement. Health of captive orcas: Survival rates and longevity. Causes of death. Stress. Aggressive behaviour towards other orcas. Aggression towards trainers. Section 5 Marine park myths Education. Conservation. Captive breeding. Research. Section 6 The display industry makes a killing Marketing the image. Lobbying. Dubious bedfellows. Drive fisheries. Over-capturing. Section 7 The times they are a-changing The future of marine parks. Changing climate of public opinion. Ethics. Alternatives to display. Whale watching. Cetacean-free facilities. Future of current captives. Release programmes. Section 8 Conclusions and recommendations Appendix: Location of current captives, and details of wild-caught orcas References The information contained in this report is believed to be correct at the time of last publication: 30th April 2001. Some information is inevitably date-sensitive: please notify the author with any comments or updated information. -

Biofilm Formation by Moraxella Catarrhalis

BIOFILM FORMATION BY MORAXELLA CATARRHALIS APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE Eric J. Hansen, Ph.D. ___________________________ Kevin S. McIver, Ph.D. ___________________________ Michael V. Norgard, Ph.D. ___________________________ Philip J. Thomas, Ph.D. ___________________________ Nicolai S.C. van Oers, Ph.D. ___________________________ BIOFILM FORMATION BY MORAXELLA CATARRHALIS by MELANIE MICHELLE PEARSON DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas Dallas, Texas March, 2004 Copyright by Melanie Michelle Pearson 2004 All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements As with any grand endeavor, there was a large supporting cast who guided me through the completion of my Ph.D. First and foremost, I would like to thank my mentor, Dr. Eric Hansen, for granting me the independence to pursue my ideas while helping me shape my work into a coherent story. I have seen that the time involved in supervising a graduate student is tremendous, and I am grateful for his advice and support. The members of my graduate committee (Drs. Michael Norgard, Kevin McIver, Phil Thomas, and Nicolai van Oers) have likewise given me a considerable investment of time and intellect. Many of the faculty, postdocs, students and staff of the Microbiology department have added to my education and made my experience here positive. Many members of the Hansen laboratory contributed to my work. Dr. Eric Lafontaine gave me my first introduction to M. catarrhalis. I hope I have learned from his example of patience, good nature, and hard work. -

Drug-Resistant Streptococcus Pneumoniae and Methicillin

NEWS & NOTES Conference Summary pneumoniae can vary among popula- conference sessions was that statically tions and is influenced by local pre- sound methods of data collection that Drug-resistant scribing practices and the prevalence capture valid, meaningful, and useful of resistant clones. Conference pre- data and meet the financial restric- Streptococcus senters discussed the role of surveil- tions of state budgets are indicated. pneumoniae and lance in raising awareness of the Active, population-based surveil- Methicillin- resistance problem and in monitoring lance for collecting relevant isolates is the effectiveness of prevention and considered the standard criterion. resistant control programs. National- and state- Unfortunately, this type of surveil- Staphylococcus level epidemiologists discussed the lance is labor-intensive and costly, aureus benefits of including state-level sur- making it an impractical choice for 1 veillance data with appropriate antibi- many states. The challenges of isolate Surveillance otic use programs designed to address collection, packaging and transport, The Centers for Disease Control the antibiotic prescribing practices of data collection, and analysis may and Prevention (CDC) convened a clinicians. The potential for local sur- place an unacceptable workload on conference on March 12–13, 2003, in veillance to provide information on laboratory and epidemiology person- Atlanta, Georgia, to discuss improv- the impact of a new pneumococcal nel. ing state-based surveillance of drug- vaccine for children was also exam- Epidemiologists from several state resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae ined; the vaccine has been shown to health departments that have elected (DRSP) and methicillin-resistant reduce infections caused by resistance to implement enhanced antimicrobial Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). -

The Use of Non-Human Primates in Research in Primates Non-Human of Use The

The use of non-human primates in research The use of non-human primates in research A working group report chaired by Sir David Weatherall FRS FMedSci Report sponsored by: Academy of Medical Sciences Medical Research Council The Royal Society Wellcome Trust 10 Carlton House Terrace 20 Park Crescent 6-9 Carlton House Terrace 215 Euston Road London, SW1Y 5AH London, W1B 1AL London, SW1Y 5AG London, NW1 2BE December 2006 December Tel: +44(0)20 7969 5288 Tel: +44(0)20 7636 5422 Tel: +44(0)20 7451 2590 Tel: +44(0)20 7611 8888 Fax: +44(0)20 7969 5298 Fax: +44(0)20 7436 6179 Fax: +44(0)20 7451 2692 Fax: +44(0)20 7611 8545 Email: E-mail: E-mail: E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Web: www.acmedsci.ac.uk Web: www.mrc.ac.uk Web: www.royalsoc.ac.uk Web: www.wellcome.ac.uk December 2006 The use of non-human primates in research A working group report chaired by Sir David Weatheall FRS FMedSci December 2006 Sponsors’ statement The use of non-human primates continues to be one the most contentious areas of biological and medical research. The publication of this independent report into the scientific basis for the past, current and future role of non-human primates in research is both a necessary and timely contribution to the debate. We emphasise that members of the working group have worked independently of the four sponsoring organisations. Our organisations did not provide input into the report’s content, conclusions or recommendations. -

Coinfection and Other Clinical Characteristics of COVID-19 In

Coinfection and Other Clinical Characteristics of COVID-19 in Children Qin Wu, MD,a,p Yuhan Xing, MD,b,p Lei Shi, MB,a,p Wenjie Li, MS,a Yang Gao, MS,a Silin Pan, PhD, MD,a Ying Wang, MS,c Wendi Wang, MS,a Quansheng Xing, PhD, MDa BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is abstract a newly identified pathogen that mainly spreads by droplets. Most published studies have been focused on adult patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), but data concerning pediatric patients are limited. In this study, we aimed to determine epidemiological characteristics and clinical features of pediatric patients with COVID-19. METHODS: We reviewed and analyzed data on pediatric patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19, including basic information, epidemiological history, clinical manifestations, laboratory and radiologic findings, treatment, outcome, and follow-up results. RESULTS: A total of 74 pediatric patients with COVID-19 were included in this study. Of the 68 case patients whose epidemiological data were complete, 65 (65 of 68; 95.59%) were household contacts of adults. Cough (32.43%) and fever (27.03%) were the predominant symptoms of 44 (59.46%) symptomatic patients at onset of the illness. Abnormalities in leukocyte count were found in 23 (31.08%) children, and 10 (13.51%) children presented with abnormal lymphocyte count. Of the 34 (45.95%) patients who had nucleic acid testing results for common respiratory pathogens, 19 (51.35%) showed coinfection with other pathogens other than SARS-CoV-2. Ten (13.51%) children had real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis for fecal specimens, and 8 of them showed prolonged existence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. -

Pneumonia: Prevention and Care at Home

FACT SHEET FOR PATIENTS AND FAMILIES Pneumonia: Prevention and Care at Home What is it? On an x-ray, pneumonia usually shows up as Pneumonia is an infection of the lungs. The infection white areas in the affected part of your lung(s). causes the small air sacs in your lungs (called alveoli) to swell and fill up with fluid or pus. This makes it harder for you to breathe, and usually causes coughing and other symptoms that sap your energy and appetite. How common and serious is it? Pneumonia is fairly common in the United States, affecting about 4 million people a year. Although for many people infection can be mild, about 1 out of every 5 people with pneumonia needs to be in the heart hospital. Pneumonia is most serious in these people: • Young children (ages 2 years and younger) • Older adults (ages 65 and older) • People with chronic illnesses such as diabetes What are the symptoms? and heart disease Pneumonia symptoms range in severity, and often • People with lung diseases such as asthma, mimic the symptoms of a bad cold or the flu: cystic fibrosis, or emphysema • Fatigue (feeling tired and weak) • People with weakened immune systems • Cough, without or without mucus • Smokers and heavy drinkers • Fever over 100ºF or 37.8ºC If you’ve been diagnosed with pneumonia, you should • Chills, sweats, or body aches take it seriously and follow your doctor’s advice. If your • Shortness of breath doctor decides you need to be in the hospital, you will receive more information on what to expect with • Chest pain or pain with breathing hospital care. -

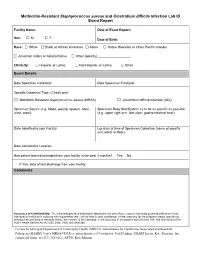

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus and Clostridium Difficile Infection Lab ID Event Report

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile Infection Lab ID Event Report Facility Name: Date of Event Report: Sex: M F □ □ Date of Birth: Race: □ White □ Black or African American □ Asian □ Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander □ American Indian or Alaska Native □ Other [specify] __________________ Ethnicity: □ Hispanic or Latino □ Not Hispanic or Latino □ Other Event Details Date Specimen Collected: Date Specimen Finalized: Specific Organism Type: (Check one) □ Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) □ Clostridium difficile Infection (CDI) Specimen Source (e.g. blood, wound, sputum, bone, Specimen Body Site/System try to be as specific as possible urine, stool): (e.g. upper right arm, foot ulcer, gastrointestinal tract): Date Admitted to your Facility: Location at time of Specimen Collection (name of specific unit, ward, or floor): Date Admitted to Location: Has patient been discharged from your facility in the past 3 months? Yes No If Yes, date of last discharge from your facility: Comments Assurance of Confidentiality: The voluntarily provided information obtained in this surveillance system that would permit identification of any individual or institution is collected with a guarantee that it will be held in strict confidence, will be used only for the purposes stated, and will not otherwise be disclosed or released without the consent of the individual, or the institution in accordance with Sections 304, 306 and 308(d) of the Public Health Service Act (42 USC 242b, 242k, and 242m(d)). For use by Michigan Department of Community Health (MDCH), Surveillance for Healthcare-Associated and Resistant Pathogens (SHARP) Unit’s MRSA/CDI Prevention Initiative (Coordinator: Gail Denkins, SHARP Intern: Kate Manton); fax completed forms to (517) 335-8263, ATTN: Kate Manton. -

Association Between Carriage of Streptococcus Pneumoniae and Staphylococcus Aureus in Children

BRIEF REPORT Association Between Carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus in Children Gili Regev-Yochay, MD Context Widespread pneumococcal conjugate vaccination may bring about epidemio- Ron Dagan, MD logic changes in upper respiratory tract flora of children. Of particular significance may Meir Raz, MD be an interaction between Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus, in view of the recent emergence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant S aureus. Yehuda Carmeli, MD, MPH Objective To examine the prevalence and risk factors of carriage of S pneumoniae Bracha Shainberg, PhD and S aureus in the prevaccination era in young children. Estela Derazne, MSc Design, Setting, and Patients Cross-sectional surveillance study of nasopharyn- geal carriage of S pneumoniae and nasal carriage of S aureus by 790 children aged 40 Galia Rahav, MD months or younger seen at primary care clinics in central Israel during February 2002. Ethan Rubinstein, MD Main Outcome Measures Carriage rates of S pneumoniae (by serotype) and S aureus; risk factors associated with carriage of each pathogen. TREPTOCOCCUS PNEUMONIAE AND Results Among 790 children screened, 43% carried S pneumoniae and 10% car- Staphylococcus aureus are com- ried S aureus. Staphylococcus aureus carriage among S pneumoniae carriers was 6.5% mon inhabitants of the upper vs 12.9% in S pneumoniae noncarriers. Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage among respiratory tract in children and S aureus carriers was 27.5% vs 44.8% in S aureus noncarriers. Only 2.8% carried both Sare responsible for common infec- pathogens concomitantly vs 4.3% expected dual carriage (P=.03). Risk factors for tions. Carriage of S aureus and S pneu- S pneumoniae carriage (attending day care, having young siblings, and age older than moniae can result in bacterial spread and 3 months) were negatively associated with S aureus carriage. -

Universidade Do Algarve Investigation of Listeria Monocytogenes And

Universidade do Algarve Investigation of Listeria monocytogenes and Streptococcus pneumoniae mutants in in vivo models of infection Ana Raquel Chaves Mendes de Alves Porfírio Dissertação para a obtenção do Grau de Mestrado em Engenharia Biológica Tese orientada pelo Prof. Dr. Peter W. Andrew e coorientada pela Prof. Dr. Maria Leonor Faleiro 2015 I Investigation of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Listeria monocytogenes mutants in in vivo models of infection Declaro ser a autora deste trabalho, que é original e inédito. Autores e trabalhos consultados estão devidamente citados no texto e constam na listagem de referências incluída. Copyright © 2015, por Ana Raquel Chaves Mendes de Alves Porfírio A Universidade do Algarve tem o direito, perpétuo e sem limites geográficos, de arquivar e publicitar este trabalho através de exemplares impressos reproduzidos em papel ou de forma digital, ou por qualquer outro meio conhecido ou que venha a ser inventado, de o divulgar através de repositórios científicos e de admitir a sua copia e distribuição com objetivos educacionais ou de investigação, não comerciais, desde que seja dado crédito ao autor e editor. II “I was taight that the way of progress was neither swift nor easy” – Marie Curie III Acknowledgements First of all I would like to thank the University of Algarve and the University of Leicester for providing me with the amazing opportunity of doing my dissertation project abroad. I wish to particularly express my deepest gratitude to my supervisors Prof. Peter Andrew and Prof. Maria Leonor Faleiro for their continuous guidance and support throughout this project. Their useful insight and feedback was thoroughly appreciated. -

Helicobacter Pylori Outer Membrane Vesicles and the Host-Pathogen Interaction

Helicobacter pylori outer membrane vesicles and the host-pathogen interaction Annelie Olofsson Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics Umeå 2013 Responsible publisher under swedish law: the Dean of the Medical Faculty This work is protected by the Swedish Copyright Legislation (Act 1960:729) ISBN: 978-91-7459-578-9 ISSN: 0346-6612 New series nr: 1559 Cover: Electron micrograph of outer membrane vesicles Elektronisk version tillgänglig på http://umu.diva-portal.org/ Printed by: VMC-KBC, Umeå University Umeå, Sweden, 2013 Till min mormor och farfar i ii INDEX ABSTRACT iv LIST OF PAPERS v SAMMANFATTNING vi ABBREVIATIONS viii INTRODUCTION 1 BACKGROUND 2 The human stomach 2 Helicobacter pylori 3 Epidemiology 3 Gastric diseases 3 Clinical outcome 4 Treatment and disease determinants 5 The gastric environment and host cell responses 6 H. pylori colonization and virulence factors 8 cagPAI 9 CagA and apical junctions 11 The H. pylori outer membrane 12 Phospholipids and cholesterol 12 Lipopolysaccharides 13 Outer membrane proteins 14 Adhesins and their cognate receptor structures 14 Bacterial outer membrane vesicles 15 Vesicle biogenesis and composition 15 Biological consequences of vesicle shedding 18 Endocytosis and uptake of bacterial vesicles 19 Clathrin-mediated endocytosis 20 Clathrin-independent endocytosis 21 Caveolae 22 Modulation of host cell defenses and responses 23 AIM OF THESIS 24 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 25 Paper I 25 Paper II 27 Paper III 28 Paper IV 31 CONCLUDING REMARKS 34 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 36 REFERENCES 38 iii ABSTRACT The gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori chronically infects the stomachs of more than half of the world’s population. Even though the majority of infected individuals remain asymptomatic, 10–20% develop peptic ulcer disease and 1–2% develop gastric cancer. -

HIV and Hepatitis C Coinfection a New Era of Treatment for People with HIV and Hepatitis C Coinfection

HIV and Hepatitis C Coinfection A new era of treatment for people with HIV and Hepatitis C Coinfection: What is HIV/Hepatitis C Coinfection? HIV and Hepatitis C coinfection means that you are living with both HIV and Hepatitis C. HIV aects your immune system and Hepatitis C (often called Hep C or HCV) is an infection that aects your liver. Hepatitis C has been one of the leading causes of illness for people with HIV – but now that is changing! 1. If you have HIV/ Hepatitis C Coinfection you are not alone. • About 30% of people living with HIV are coinfected with Hepatitis C. • The rate is even higher (50-90%) for people living with HIV who have a history of injection drug use and are coinfected with Hepatitis C. Gay men living with HIV should know the facts. Men who have sex with men who are living with HIV are at increased risk of getting Hepatitis C during sex. The risk is highest when blood is present during sex, for example during anal intercourse or rough sex. Using condoms, lots of lube and preventing bleeding during sex can help protect you from Hepatitis C. New treatments for Hepatitis C have changed everything. Old Treatments New Treatments • Not very eective • 90 -100% cure rate • Serious side eects • Few or no side eects • Risks outweighed benefits • Almost everyone can for most people benefit from treatment If you were not eligible for the old treatments or if you had treatment and it didn’t work, you will most likely be able to benefit from the new treatment! 2. -

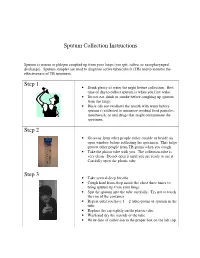

Sputum Collection Instructions Step 1 Step 2 Step 3

Sputum Collection Instructions Sputum is mucus or phlegm coughed up from your lungs (not spit, saliva, or nasopharyngeal discharge). Sputum samples are used to diagnose active tuberculosis (TB) and to monitor the effectiveness of TB treatment. Step 1 • Drink plenty of water the night before collection. Best time of day to collect sputum is when you first wake. • Do not eat, drink or smoke before coughing up sputum from the lungs. • Rinse (do not swallow) the mouth with water before sputum is collected to minimize residual food particles, mouthwash, or oral drugs that might contaminate the specimen. Step 2 • Go away from other people either outside or beside an open window before collecting the specimen. This helps protect other people from TB germs when you cough. • Take the plastic tube with you. The collection tube is very clean. Do not open it until you are ready to use it. Carefully open the plastic tube. Step 3 • Take several deep breaths. • Cough hard from deep inside the chest three times to bring sputum up from your lungs. • Spit the sputum into the tube carefully. Try not to touch the rim of the container. • Repeat until you have 1 – 2 tablespoons of sputum in the tube. • Replace the cap tightly on the plastic tube. • Wash and dry the outside of the tube. • Write date of collection in the proper box on the lab slip. Step 4 • Place the primary specimen container (usually a conical centrifuge tube) in the clear plastic baggie that has the biohazard symbol imprint. • Place the white absorbent sheet in the plastic baggie.