Chest Pain in Pediatrics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Approach to Cyanosis in a Neonate.Pdf

PedsCases Podcast Scripts This podcast can be accessed at www.pedscases.com, Apple Podcasting, Spotify, or your favourite podcasting app. Approach to Cyanosis in a Neonate Developed by Michelle Fric and Dr. Georgeta Apostol for PedsCases.com. June 29, 2020 Introduction Hello, and welcome to this pedscases podcast on an approach to cyanosis in a neonate. My name is Michelle Fric and I am a fourth-year medical student at the University of Alberta. This podcast was made in collaboration with Dr. Georgeta Apostol, a general pediatrician at the Royal Alexandra Hospital Pediatrics Clinic in Edmonton, Alberta. Cyanosis refers to a bluish discoloration of the skin or mucous membranes and is a common finding in newborns. It is a clinical manifestation of the desaturation of arterial or capillary blood and may indicate serious hemodynamic instability. It is important to have an approach to cyanosis, as it can be your only sign of a life-threatening illness. The goal of this podcast is to develop this approach to a cyanotic newborn with a focus on these can’t miss diagnoses. After listening to this podcast, the learner should be able to: 1. Define cyanosis 2. Assess and recognize a cyanotic infant 3. Develop a differential diagnosis 4. Identify immediate investigations and management for a cyanotic infant Background Cyanosis can be further broken down into peripheral and central cyanosis. It is important to distinguish these as it can help you to formulate a differential diagnosis and identify cases that are life-threatening. Peripheral cyanosis affects the distal extremities resulting in blue color of the hands and feet, while the rest of the body remains pinkish and well perfused. -

Heart Disease in Children.Pdf

Heart Disease in Children Richard U. Garcia, MD*, Stacie B. Peddy, MD KEYWORDS Congenital heart disease Children Primary care Cyanosis Chest pain Heart murmur Infective endocarditis KEY POINTS Fetal and neonatal diagnosis of congenital heart disease (CHD) has improved the out- comes for children born with critical CHD. Treatment and management of CHD has improved significantly over the past 2 decades, allowing more children with CHD to grow into adulthood. Appropriate diagnosis and treatment of group A pharyngitis and Kawasaki disease in pe- diatric patients mitigate late complications. Chest pain, syncope, and irregular heart rhythm are common presentations in primary care. Although typically benign, red flag symptoms/signs should prompt a referral to car- diology for further evaluation. INTRODUCTION The modern incidence of congenital heart disease (CHD) has been reported at 6 to 11.1 per 1000 live births.1,2 The true incidence is likely higher because many miscar- riages are due to heart conditions incompatible with life. The unique physiology of CHD, the constantly developing nature of children, the differing presenting signs and symptoms, the multiple palliative or corrective surgeries, and the constant devel- opment of new strategies directed toward improving care in this population make pe- diatric cardiology an exciting field in modern medicine. THE FETAL CIRCULATION AND TRANSITION TO NEONATAL LIFE Cardiovascular morphogenesis is a complex process that transforms an initial single- tube heart to a 4-chamber heart with 2 separate outflow tracts. Multiple and Disclosure Statement: All Authors take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the information presented and their discussed interpretation. -

Review of Systems

code: GF004 REVIEW OF SYSTEMS First Name Middle Name / MI Last Name Check the box if you are currently experiencing any of the following : General Skin Respiratory Arthritis/Rheumatism Abnormal Pigmentation Any Lung Troubles Back Pain (recurrent) Boils Asthma or Wheezing Bone Fracture Brittle Nails Bronchitis Cancer Dry Skin Chronic or Frequent Cough Diabetes Eczema Difficulty Breathing Foot Pain Frequent infections Pleurisy or Pneumonia Gout Hair/Nail changes Spitting up Blood Headaches/Migraines Hives Trouble Breathing Joint Injury Itching URI (Cold) Now Memory Loss Jaundice None Muscle Weakness Psoriasis Numbness/Tingling Rash Obesity Skin Disease Osteoporosis None Rheumatic Fever Weight Gain/Loss None Cardiovascular Gastrointestinal Eyes - Ears - Nose - Throat/Mouth Awakening in the night smothering Abdominal Pain Blurring Chest Pain or Angina Appetite Changes Double Vision Congestive Heart Failure Black Stools Eye Disease or Injury Cyanosis (blue skin) Bleeding with Bowel Movements Eye Pain/Discharge Difficulty walking two blocks Blood in Vomit Glasses Edema/Swelling of Hands, Feet or Ankles Chrohn’s Disease/Colitis Glaucoma Heart Attacks Constipation Itchy Eyes Heart Murmur Cramping or pain in the Abdomen Vision changes Heart Trouble Difficulty Swallowing Ear Disease High Blood Pressure Diverticulosis Ear Infections Irregular Heartbeat Frequent Diarrhea Ears ringing Pain in legs Gallbladder Disease Hearing problems Palpitations Gas/Bloating Impaired Hearing Poor Circulation Heartburn or Indigestion Chronic Sinus Trouble Shortness -

Chest Pain in Children and Adolescents Surendranath R

Article cardiology Chest Pain in Children and Adolescents Surendranath R. Veeram Objectives After completing this article, readers should be able to: Reddy, MD,* Harinder R. Singh, MD* 1. Enumerate the most common causes of chest pain in pediatric patients. 2. Differentiate cardiac chest pain from that of noncardiac cause. 3. Describe the detailed evaluation of a pediatric patient who has chest pain. Author Disclosure 4. Screen and identify patients who require a referral to a pediatric cardiologist or other Drs Veeram Reddy specialist. and Singh have 5. Explain the management of the common causes of pediatric chest pain. disclosed no financial relationships relevant Case Studies to this article. This Case 1 commentary does not During an annual physical examination, a 12-year-old girl complains of intermittent chest contain a discussion pain for the past 5 days that localizes to the left upper sternal border. The pain is sharp and of an unapproved/ stabbing, is 5/10 in intensity, increases with deep breathing, and lasts for less than 1 minute. investigative use of a The patient has no history of fever, cough, exercise intolerance, palpitations, dizziness, or commercial product/ syncope. On physical examination, the young girl is in no pain or distress and has normal vital signs for her age. Examination of her chest reveals no signs of inflammation over the sternum device. or rib cage. Palpation elicits mild-to-moderate tenderness over the left second and third costochondral junctions. The patient reports that the pain during the physical examination is similar to the chest pain she has experienced for the past 5 days. -

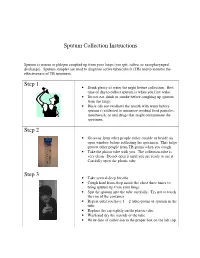

Sputum Collection Instructions Step 1 Step 2 Step 3

Sputum Collection Instructions Sputum is mucus or phlegm coughed up from your lungs (not spit, saliva, or nasopharyngeal discharge). Sputum samples are used to diagnose active tuberculosis (TB) and to monitor the effectiveness of TB treatment. Step 1 • Drink plenty of water the night before collection. Best time of day to collect sputum is when you first wake. • Do not eat, drink or smoke before coughing up sputum from the lungs. • Rinse (do not swallow) the mouth with water before sputum is collected to minimize residual food particles, mouthwash, or oral drugs that might contaminate the specimen. Step 2 • Go away from other people either outside or beside an open window before collecting the specimen. This helps protect other people from TB germs when you cough. • Take the plastic tube with you. The collection tube is very clean. Do not open it until you are ready to use it. Carefully open the plastic tube. Step 3 • Take several deep breaths. • Cough hard from deep inside the chest three times to bring sputum up from your lungs. • Spit the sputum into the tube carefully. Try not to touch the rim of the container. • Repeat until you have 1 – 2 tablespoons of sputum in the tube. • Replace the cap tightly on the plastic tube. • Wash and dry the outside of the tube. • Write date of collection in the proper box on the lab slip. Step 4 • Place the primary specimen container (usually a conical centrifuge tube) in the clear plastic baggie that has the biohazard symbol imprint. • Place the white absorbent sheet in the plastic baggie. -

Perinatal/Neonatal Case Presentation

Perinatal/Neonatal Case Presentation &&&&&&&&&&&&&& Urinary Tract Infection With Trichomonas vaginalis in a Premature Newborn Infant and the Development of Chronic Lung Disease David J. Hoffman, MD vaginal bleeding with suspected abruption resulted in delivery of Gerard D. Brown, DO the infant by Cesarean section. The Apgar scores were 1, 5, and 9 Frederick H. Wirth, MD at 1, 5, and 10 minutes of life, respectively. Betsy S. Gebert, CRNP After delivery, the infant was managed with mechanical Cathy L. Bailey, MS, CRNP ventilation with pressure support and volume guarantee for Endla K. Anday, MD respiratory distress syndrome. She received exogenous surfactant We report a case of a low-birth-weight infant with an infection of the urinary tract with Trichomonas vaginalis, who later developed cystic chronic lung disease suggestive of Wilson-Mikity syndrome. Although she had mild respiratory distress syndrome at birth, the extent of the chronic lung disease was out of proportion to the initial illness. We speculate that maternal infection with this organism may have resulted in an inflammatory response that led to its development. Journal of Perinatology (2003) 23, 59 – 61 doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7210819 CASE PRESENTATION A 956-g, appropriate-for-gestational-age, African–American female was delivered by Cesarean section following 27 5/7 weeks of gestation in breech presentation after a period of advanced cervical dilatation and uterine contractions. Her mother was a 20-year-old gravida 5, para 2022 woman whose prenatal laboratory data were significant for vaginal colonization with Streptococcus agalactiae, treatment for Chlamydia trachomatis, and a history of cocaine and marijuana usage confirmed by urine toxicology. -

A Case of Extreme Hypercapnia

119 Emerg Med J: first published as 10.1136/emj.2003.005009 on 20 January 2004. Downloaded from CASE REPORTS A case of extreme hypercapnia: implications for the prehospital and accident and emergency department management of acutely dyspnoeic patients L Urwin, R Murphy, C Robertson, A Pollok ............................................................................................................................... Emerg Med J 2004;21:119–120 64 year old woman was brought by ambulance to the useful non-invasive technique to aid the assessment of accident and emergency department. She had been peripheral oxygen saturation. In situations of poor perfusion, Areferred by her GP because of increasing dyspnoea, movement and abnormal haemoglobin, however, this tech- cyanosis, and lethargy over the previous four days. On arrival nique may not reliably reflect PaO2 values. More importantly, of the ambulance crew at her home she was noted to be and as shown in our case, there is no definite relation tachycardic and tachypnoeic (respiratory rate 36/min) with a between SaO2 values measured by pulse oximetry and PaCO2 GCS of 5 (E 3, M 1, V 1). She was given oxygen at 6 l/min via values although it has been shown that the more oxygenated a Duo mask, and transferred to hospital. The patient arrived at the accident and emergency department 18 minutes later. In transit, there had been a clinical deterioration. The GCS was now 3 and the respiratory rate 4/min. Oxygen saturation, as measured by a pulse oximeter was 99%. The patient was intubated and positive pressure ventilation started. Arterial blood gas measurements taken at the time of intubation were consistent with acute on chronic respiratory failure (fig 1). -

Identifying and Treating Chest Pain

Identifying and Treating Chest Pain The Congenital Heart Collaborative Cardiac Chest Pain University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital Chest pain due to a cardiac condition is rare in children and and Nationwide Children’s Hospital have formed an innovative adolescents, with a prevalence of less than 5 percent. The affiliation for the care of patients with congenital heart disease cardiac causes of chest pain include inflammation, coronary from fetal life to adulthood. The Congenital Heart Collaborative insufficiency, tachyarrhythmias, left ventricular outflow tract provides families with access to one of the most extensive and obstruction and connective tissue abnormalities. experienced heart teams – highly skilled in the delivery of quality clinical services, novel therapies and a seamless continuum of care. Noncardiac Chest Pain Noncardiac chest pain is, by far, the most common cause of chest pain in children and adolescents, accounting for 95 percent of Pediatric Chest Pain concerns. Patients are often unnecessarily referred to a pediatric In pediatrics, chest pain has a variety of symptomatic levels and cardiologist for symptoms. This causes increased anxiety and causes. It can range from a sharp stab to a dull ache; a crushing distress within the family. Noncardiac causes of chest pain are or burning sensation; or even pain that travels up to the neck, musculoskeletal, pulmonary, gastrointestinal and miscellaneous. jaw and back. Chest pain can be cause for alarm in both patients The most common cause of chest pain in children and and parents, and it warrants careful examination and treatment. adolescents is musculoskeletal or chest-wall pain. Pediatric chest pain can be broadly classified as cardiac chest pain Reassurance, rest and analgesia are the primary treatments or noncardiac chest pain. -

Kounis Syndrome: a Forgotten Cause of References Chest Pain/ Cardiac Chest Pain in Children 1

382 Editöre Mektuplar Letters to the Editor Kounis syndrome: A forgotten cause of References chest pain/ Cardiac chest pain in children 1. Çağdaş DN, Paç FA. Cardiac chest pain in children. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg 2009;9:401-6. Kounis sendromu: Göğüs ağrısının unutulan bir sebebi/ 2. Coleman WL. Recurrent chest pain in children. Pediatr Clin North Am Çocuklarda kardiyak göğüs ağrısı 1984;31:1007-26. 3. Kounis NG. Kounis syndrome (allergic angina and allergic myocardial infarction): a natural paradigm? Int J Cardiol 2006; 7:7-14. Dear Editor, 4. Biteker M, Duran NE, Biteker F, Civan HA, Gündüz S, Gökdeniz T, et al. Kounis syndrome: first series in Turkish patients. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg I read with interest the article “Cardiac chest pain in children” by 2009;9:59-60. Çağdaş et al. (1) which has retrospectively evaluated 120 children 5. Biteker M. A new classification of Kounis syndrome. Int J Cardiol 2010 Jun admitted to a pediatric cardiology clinic with chest pain. Although chest 7. [Epub ahead of print]. pain in children is rarely reported to be associated with cardiac 6. Biteker M, Duran NE, Ertürk E, Aykan AC, Civan HA, et al. Kounis Syndrome diseases in the literature (2) authors have found that 52 of the patients secondary to amoxicillin/clavulanic acid use in a child. Int J Cardiol 2009;136:e3-5. (42.5%) had cardiac diseases and 28 (23.3%) of these patients’ cardiac 7. Biteker M, Ekşi Duran N, Sungur Biteker F, Ayyıldız Civan H, Kaya H, diseases were thought to directly cause their chest pain. -

Keepthebeatconference 2014

Texas Children’s HOSPITAL keepthebeatconference 2014 Thursday, May 1 – Saturday, May 3, 2014 Presented by Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine Texas Children’s Pavilion for Women 4th Floor Conference Center n 6621 Fannin Street n Houston, TX 77030 THIS year’S PROGRAM INCLUDES TWO EXCITING TRACKS! INPATIENT CARDIOLOGY OUTPATIENT CARDIOLOGY TRACK TRACK View program and register online at View program and register online at BaylorCME.org/CME/1489-MI BaylorCME.org/CME/1489-MO HEART MURMUR WORKSHOP MAY 3 View page 8 for more information. Co-sponsored by Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine PLANNING COMMITTEE Silvana M. Lawrence, MD, PhD Director, Community and Program Development, Texas Children’s Hospital Associate Professor of Pediatrics, Baylor Collge of Medicine William B. Kyle, MD Pediatric Cardiologist, Texas Children’s Hospital Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Baylor Collge of Medicine Priscila P. Reid, RN, FNP-C, PNP-AC Nurse Practitioner, Texas Children’s Hospital Instructor of Pediatrics, Baylor Collge of Medicine GUEST FACULTY Jane Burns, MD Chitra Ravishankar, MD Professor of Pediatrics Assistant Professor of Pediatrics University of California - San Diego University of Pennsylvania Ganga Krishnamurthy, MD Marah N. Short Assistant Professor of Pediatrics Senior Staff Researcher Columbia University James A. Baker, III Institute for Public Policy Rice University BAYLOR COLLEGE OF MEDICINE FACULTY Steven A. Abrams, MD Jeffrey S. Heinle, MD Christina Y. Miyake, MD Professor of Pediatrics Associate Professor of Surgery Assistant Professor of Pediatrics Hugh D. Allen, MD Aamir Jeewa, MD Antonio R. Mott, MD Professor of Pediatrics Assistant Professor of Pediatrics Associate Professor of Pediatrics Carolyn A. -

Pertussis Death Worksheet Instructions 1

Appendix 12.1 Pertussis Death Worksheet Instructions 1. Decedent State of Residence: State of decedent’s residence at time of cough onset. 2. State Surveillance ID: State-assigned, unique identifier assigned to pertussis case-patients. If the decedent did not meet the CSTE pertussis case definition for reporting, this field should be left blank. 3. County of Residence: County of decedent’s residence at time of cough onset. 4. State Where Death Occurred: State where the decedent expired, which may differ from the state of residence if the decedent was treated or hospitalized away from home. 5. Date of Birth: Birth date of the decedent in MM/DD/YYYY format. 6. Country of Birth: Country where the decedent was born. 7. Gestational age at birth: For decedents <1 year of age at time of cough onset, record the number of completed weeks of gestation at birth. This data element should be left blank for case-patients ≥1 year of age. 8. Cough Onset Date: Date on which the decedent experienced first cough during the course of illness in MM/DD/YYYY format. 9. Date of Death: Date on which the decedent expired in MM/DD/YYYY format. 10. Sex: Indicate whether decedent is Male or Female. 11. Race: Decedent’s race reported by next of kin or recorded from medical records/death certificate; more than one option may be recorded. 12. Ethnicity: Decedent’s ethnicity reported by next of kin or recorded from medical records/death certificate. 13. Clinical Symptoms—General Instructions: Select all of the clinical symptoms that the decedent experienced during the course of illness preceding their death. -

Evaluation of Upper Airway Changes Following Surgical Removal of the Adenoids Using 3-D Cone Beam CT

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC Theses & Dissertations Graduate Studies Fall 12-18-2015 Evaluation of Upper Airway Changes Following Surgical Removal of the Adenoids Using 3-D Cone Beam CT Christopher C. Schultz University of Nebraska Medical Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/etd Part of the Other Medical Specialties Commons Recommended Citation Schultz, Christopher C., "Evaluation of Upper Airway Changes Following Surgical Removal of the Adenoids Using 3-D Cone Beam CT" (2015). Theses & Dissertations. 54. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/etd/54 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVALUATION OF UPPER AIRWAY CHANGES FOLLOWING SURGICAL REMOVAL OF THE ADENOIDS USING 3-D CONE BEAM CT By Christopher C. Schultz, D.D.S A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College in the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Medical Sciences Interdepartmental Area Oral Biology University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, Nebraska December, 2015 Advisory Committee: Sundaralingam Premaraj, BDS, MS, PhD, FRCD(C) Sheela Premaraj, BDS, PhD Peter J. Giannini, DDS, MS Stanton D. Harn, PhD i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my thanks and gratitude to the members of my thesis committee: Dr. Sundaralingam Premaraj, Dr. Sheela Premaraj, Dr. Peter Giannini, and Dr. Stanton Harn. Your advice and assistance has been vital for the completion of the project.