Association Between Carriage of Streptococcus Pneumoniae and Staphylococcus Aureus in Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drug-Resistant Streptococcus Pneumoniae and Methicillin

NEWS & NOTES Conference Summary pneumoniae can vary among popula- conference sessions was that statically tions and is influenced by local pre- sound methods of data collection that Drug-resistant scribing practices and the prevalence capture valid, meaningful, and useful of resistant clones. Conference pre- data and meet the financial restric- Streptococcus senters discussed the role of surveil- tions of state budgets are indicated. pneumoniae and lance in raising awareness of the Active, population-based surveil- Methicillin- resistance problem and in monitoring lance for collecting relevant isolates is the effectiveness of prevention and considered the standard criterion. resistant control programs. National- and state- Unfortunately, this type of surveil- Staphylococcus level epidemiologists discussed the lance is labor-intensive and costly, aureus benefits of including state-level sur- making it an impractical choice for 1 veillance data with appropriate antibi- many states. The challenges of isolate Surveillance otic use programs designed to address collection, packaging and transport, The Centers for Disease Control the antibiotic prescribing practices of data collection, and analysis may and Prevention (CDC) convened a clinicians. The potential for local sur- place an unacceptable workload on conference on March 12–13, 2003, in veillance to provide information on laboratory and epidemiology person- Atlanta, Georgia, to discuss improv- the impact of a new pneumococcal nel. ing state-based surveillance of drug- vaccine for children was also exam- Epidemiologists from several state resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae ined; the vaccine has been shown to health departments that have elected (DRSP) and methicillin-resistant reduce infections caused by resistance to implement enhanced antimicrobial Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). -

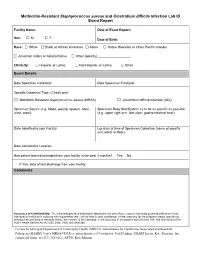

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus and Clostridium Difficile Infection Lab ID Event Report

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile Infection Lab ID Event Report Facility Name: Date of Event Report: Sex: M F □ □ Date of Birth: Race: □ White □ Black or African American □ Asian □ Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander □ American Indian or Alaska Native □ Other [specify] __________________ Ethnicity: □ Hispanic or Latino □ Not Hispanic or Latino □ Other Event Details Date Specimen Collected: Date Specimen Finalized: Specific Organism Type: (Check one) □ Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) □ Clostridium difficile Infection (CDI) Specimen Source (e.g. blood, wound, sputum, bone, Specimen Body Site/System try to be as specific as possible urine, stool): (e.g. upper right arm, foot ulcer, gastrointestinal tract): Date Admitted to your Facility: Location at time of Specimen Collection (name of specific unit, ward, or floor): Date Admitted to Location: Has patient been discharged from your facility in the past 3 months? Yes No If Yes, date of last discharge from your facility: Comments Assurance of Confidentiality: The voluntarily provided information obtained in this surveillance system that would permit identification of any individual or institution is collected with a guarantee that it will be held in strict confidence, will be used only for the purposes stated, and will not otherwise be disclosed or released without the consent of the individual, or the institution in accordance with Sections 304, 306 and 308(d) of the Public Health Service Act (42 USC 242b, 242k, and 242m(d)). For use by Michigan Department of Community Health (MDCH), Surveillance for Healthcare-Associated and Resistant Pathogens (SHARP) Unit’s MRSA/CDI Prevention Initiative (Coordinator: Gail Denkins, SHARP Intern: Kate Manton); fax completed forms to (517) 335-8263, ATTN: Kate Manton. -

Clostridium Difficile Infection: How to Deal with the Problem DH INFORMATION RE ADER B OX

Clostridium difficile infection: How to deal with the problem DH INFORMATION RE ADER B OX Policy Estates HR / Workforce Commissioning Management IM & T Planning / Finance Clinical Social Care / Partnership Working Document Purpose Best Practice Guidance Gateway Reference 9833 Title Clostridium difficile infection: How to deal with the problem Author DH and HPA Publication Date December 2008 Target Audience PCT CEs, NHS Trust CEs, SHA CEs, Care Trust CEs, Medical Directors, Directors of PH, Directors of Nursing, PCT PEC Chairs, NHS Trust Board Chairs, Special HA CEs, Directors of Infection Prevention and Control, Infection Control Teams, Health Protection Units, Chief Pharmacists Circulation List Description This guidance outlines newer evidence and approaches to delivering good infection control and environmental hygiene. It updates the 1994 guidance and takes into account a national framework for clinical governance which did not exist in 1994. Cross Ref N/A Superseded Docs Clostridium difficile Infection Prevention and Management (1994) Action Required CEs to consider with DIPCs and other colleagues Timing N/A Contact Details Healthcare Associated Infection and Antimicrobial Resistance Department of Health Room 528, Wellington House 133-155 Waterloo Road London SE1 8UG For Recipient's Use Front cover image: Clostridium difficile attached to intestinal cells. Reproduced courtesy of Dr Jan Hobot, Cardiff University School of Medicine. Clostridium difficile infection: How to deal with the problem Contents Foreword 1 Scope and purpose 2 Introduction 3 Why did CDI increase? 4 Approach to compiling the guidance 6 What is new in this guidance? 7 Core Guidance Key recommendations 9 Grading of recommendations 11 Summary of healthcare recommendations 12 1. -

Universidade Do Algarve Investigation of Listeria Monocytogenes And

Universidade do Algarve Investigation of Listeria monocytogenes and Streptococcus pneumoniae mutants in in vivo models of infection Ana Raquel Chaves Mendes de Alves Porfírio Dissertação para a obtenção do Grau de Mestrado em Engenharia Biológica Tese orientada pelo Prof. Dr. Peter W. Andrew e coorientada pela Prof. Dr. Maria Leonor Faleiro 2015 I Investigation of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Listeria monocytogenes mutants in in vivo models of infection Declaro ser a autora deste trabalho, que é original e inédito. Autores e trabalhos consultados estão devidamente citados no texto e constam na listagem de referências incluída. Copyright © 2015, por Ana Raquel Chaves Mendes de Alves Porfírio A Universidade do Algarve tem o direito, perpétuo e sem limites geográficos, de arquivar e publicitar este trabalho através de exemplares impressos reproduzidos em papel ou de forma digital, ou por qualquer outro meio conhecido ou que venha a ser inventado, de o divulgar através de repositórios científicos e de admitir a sua copia e distribuição com objetivos educacionais ou de investigação, não comerciais, desde que seja dado crédito ao autor e editor. II “I was taight that the way of progress was neither swift nor easy” – Marie Curie III Acknowledgements First of all I would like to thank the University of Algarve and the University of Leicester for providing me with the amazing opportunity of doing my dissertation project abroad. I wish to particularly express my deepest gratitude to my supervisors Prof. Peter Andrew and Prof. Maria Leonor Faleiro for their continuous guidance and support throughout this project. Their useful insight and feedback was thoroughly appreciated. -

Streptococcus Pneumoniae Technical Sheet

technical sheet Streptococcus pneumoniae Classification On necropsy, a serosanguineous to purulent exudate Alpha-hemolytic, Gram-positive, encapsulated, aerobic is often found in the nasal cavities and the tympanic diplococcus bullae. The lungs can have areas of firm, dark red consolidation. Fibrinopurulent pleuritis, pericarditis, Family and peritonitis are other changes seen on necropsy of animals affected by S. pneumoniae. Histologic Streptococcaceae lesions are consistent with necropsy findings, Affected species and bronchopneumonia of varying severity and fibrinopurulent serositis are often seen. Primarily described as a pathogen of rats and guinea pigs. Mice are susceptible to infection. Agent of human Diagnosis disease and human carriers are a likely source of An S. pneumoniae infection should be suspected if animal infections. Zoonotic infection is possible. encapsulated Gram-positive diplococci are seen on a smear from a lesion. Confirmation of the diagnosis is Frequency via culture of lesions or affected tissues. S. pneumoniae Rare in modern laboratory animal colonies. Prevalence grows best on 5% blood agar and is alpha-hemolytic. in pet and wild populations unknown. The organism is then presumptively identified with an optochin test. PCR assays are also available for Transmission diagnosis. PCR-based screening for S. pneumoniae Transmission is primarily via aerosol or contact with may be conducted on respiratory samples or feces. nasal or lacrimal secretions of an infected animal. S. PCR may also be useful for confirmation of presumptive pneumoniae may be cultured from the nasopharynx and microbiologic identification or confirming the identity of tympanic bullae. bacteria observed in histologic lesions. Clinical Signs and Lesions Interference with Research Inapparent infections and carrier states are common, Animals carrying S. -

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA)

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) Over the past several decades, the incidence of resistant gram-positive organisms has risen in the United States. MRSA strains, first identified in the 1960s in England, were first observed in the U.S. in the mid 1980s.1 Resistance quickly developed, increasing from 2.4% in 1979 to 29% in 1991.2 The current prevalence for MRSA in hospitals and other facilities ranges from <10% to 65%. In 1999, MRSA accounted for more than 50% of all Staphylococcus aureus isolates within U.S. intensive care units.3, 4 The past years, however, outbreaks of MRSA have also been seen in the community setting, particularly among preschool-age children, some of whom have attended day-care centers.5, 6, 7 MRSA does not appear to be more virulent than methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, but certainly poses a greater treatment challenge. MRSA also has been associated with higher hospital costs and mortality.8 Within a decade of its development, methicillin resistance to Staphylococcus aureus emerged.9 MRSA strains generally are now resistant to other antimicrobial classes including aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, carbapenems, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and macrolides.10,11 Most of the resistance was secondary to production of beta-lactamase enzymes or intrinsic resistance with alterations in penicillin-binding proteins. Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequent cause of nosocomial pneumonia and surgical- wound infections and the second most common cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections.12 Long-term care facilities (LTCFs) have developed rates of MRSA ranging from 25%-35%. MRSA rates may be higher in LTCFs if they are associated with hospitals that have higher rates.13 Transmission of MRSA generally occurs through direct or indirect contact with a reservoir. -

Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA)

Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Clostridium difficile and ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in the home and community: assessing the problem, controlling the spread An expert report commissioned by the International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene © International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene, 2006 2 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 4 SUMMARY 5 1. INTRODUCTION – INFECTIOUS DISEASE AND HYGIENE IN THE 21ST CENTURY 7 2. THE CHAIN OF INFECTION TRANSMISSION IN THE HOME 10 3. METHICILLIN RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS (MRSA) 11 3.1 CHARACTERISTICS OF STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS AND METHICILLIN RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS 11 3.2 HOSPITAL-ACQUIRED, HEALTHCARE ASSOCIATED AND COMMUNITY ACQUIRED MRSA 11 3.3 UNDERSTANDING THE CHAIN OF INFECTION FOR S. AUREUS AND MRSA IN THE HOME 13 3.4 WHAT ARE THE RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH S. AUREUS AND MRSA IN THE COMMUNITY? 22 4. CLOSTRIDIUM DIFFICILE 24 4.1 CHARACTERISTICS OF CLOSTRIDIUM DIFFICILE 24 4.2 HOSPITAL-ACQUIRED AND COMMUNITY- ACQUIRED C. DIFFICILE 24 4.3 UNDERSTANDING THE CHAIN OF INFECTION FOR C. DIFFICILE IN THE HOME 25 4.4 WHAT ARE THE RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH C. DIFFICILE IN THE HOME AND COMMUNITY 28 5. EXTENDED-SPECTRUM ß-LACTAMASE ESCHERICHIA COLI (ESBLS) 30 5.1 CHARACTERISTICS OF ESCHERICHIA COLI 30 5.2 HOSPITAL AND COMMUNITY-ACQUIRED ESBL-PRODUCING E. COLI INFECTIONS 31 5.3 UNDERSTANDING THE CHAIN OF INFECTION FOR E. COLI AND ESBL-PRODUCING E. COLI IN THE HOME 31 5.4 RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH ESBLS IN THE COMMUNITY 33 6. REDUCING THE RISKS OF TRANSMISSION OF METHICILLIN RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS (MRSA), CLOSTRIDIUM DIFFICILE AND ESBL-PRODUCING ESCHERICHIA COLI IN THE HOME AND COMMUNITY - DEVELOPING A RISK-BASED APPROACH TO HOME HYGIENE 35 6.1 BREAKING THE CHAIN OF TRANSMISSION OF INFECTION IN THE HOME 35 6.2 DEVELOPING A RISK-BASED APPROACH TO HOME HYGIENE 35 6.3 INTERRUPTING THE CHAIN OF INFECTION TRANSMISSION IN THE HOME 38 7. -

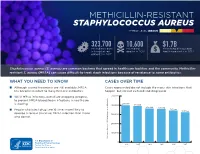

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Threat Level Serious

METHICILLIN-RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS THREAT LEVEL SERIOUS 323,700 10,600 $1.7B Estimated cases Estimated Estimated attributable in hospitalized deaths in 2017 healthcare costs in 2017 patients in 2017 Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) are common bacteria that spread in healthcare facilities and the community. Methicillin- resistant S. aureus (MRSA) can cause difficult-to-treat staph infections because of resistance to some antibiotics. WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW CASES OVER TIME ■ Although several treatments are still available, MRSA Cases represented do not include the many skin infections that has become resistant to many first-line antibiotics. happen, but are not cultured and diagnosed. ■ While MRSA infections overall are dropping, progress 500,000 to prevent MRSA bloodstream infections in healthcare 401,000 is slowing. 400,000 391,000 365,400 359,500 ■ People who inject drugs are 16 times more likely to 343,100 323,700 develop a serious (invasive) MRSA infection than those 300,000 who do not. 200,000 100,000 Estimated Cases of MRSA in Hospitalized Patients in Hospitalized Cases of MRSA Estimated 0 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 30 25 An estimated 7% decline each year 20 15 10 An estimated 17% decline each year from 2005 to 2016, and no change from 2013 to 2016 5 Estimated Cases of MRSA Per 100,000 People 100,000 Per Cases of MRSA Estimated 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Community-onset MRSA Bloodstream Infection Rate Hospital-onset MRSA Bloodstream Infection Rate 500,000 401,000 400,000 391,000 365,400 359,500 343,100 323,700 300,000 METHICILLIN-RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS200,000 (MRSA) MRSA INFECTIONS CAN BE PREVENTED REDUCTIONS100,000 IN HOSPITALS HAVE STALLED MRSA infections are preventable and many lives have been New Patients in Hospitalized Cases of MRSA Estimated strategies in healthcare, along with current CDC 0 saved through effective infection control interventions. -

Streptococci

STREPTOCOCCI Streptococci are Gram-positive, nonmotile, nonsporeforming, catalase-negative cocci that occur in pairs or chains. Older cultures may lose their Gram-positive character. Most streptococci are facultative anaerobes, and some are obligate (strict) anaerobes. Most require enriched media (blood agar). Streptococci are subdivided into groups by antibodies that recognize surface antigens (Fig. 11). These groups may include one or more species. Serologic grouping is based on antigenic differences in cell wall carbohydrates (groups A to V), in cell wall pili-associated protein, and in the polysaccharide capsule in group B streptococci. Rebecca Lancefield developed the serologic classification scheme in 1933. β-hemolytic strains possess group-specific cell wall antigens, most of which are carbohydrates. These antigens can be detected by immunologic assays and have been useful for the rapid identification of some important streptococcal pathogens. The most important groupable streptococci are A, B and D. Among the groupable streptococci, infectious disease (particularly pharyngitis) is caused by group A. Group A streptococci have a hyaluronic acid capsule. Streptococcus pneumoniae (a major cause of human pneumonia) and Streptococcus mutans and other so-called viridans streptococci (among the causes of dental caries) do not possess group antigen. Streptococcus pneumoniae has a polysaccharide capsule that acts as a virulence factor for the organism; more than 90 different serotypes are known, and these types differ in virulence. Fig. 1 Streptococci - clasiffication. Group A streptococci causes: Strep throat - a sore, red throat, sometimes with white spots on the tonsils Scarlet fever - an illness that follows strep throat. It causes a red rash on the body. -

Pneumococcal Disease (Sickness Caused by Streptococcus Pneumoniae)

Pneumococcal Disease (Sickness Caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae) What is pneumococcal disease? Pneumococcal disease is an infection caused by the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae. It's also called pneumococcus and can cause ear infections, pneumonia, infections in the blood and meningitis. When does it happen? Children can get pneumococcal disease any time of the year. What are the symptoms? Fever and increased fussiness or irritability are common Meningitis symptoms include fever, trouble bending or moving the neck, increased fussiness or irritability, and headache in anyone over age 2. In babies, the only symptoms may be that the baby is less active, fussy or crying more than usual, throwing up, or not eating normally. Pneumonia symptoms in children include fever, cough, working hard to breathe, breathing faster than usual or grunting. Ear infection symptoms are ears that hurt, crying or pulling on ears, sore throat or pain when swallowing. Children may also be sleepy, have a fever, and be fussy. Is it contagious? How is it spread? Pneumococcus is spread by contact with people who either have a pneumococcal illness or who carry the bacteria in their throats without being sick. It can be spread by droplets in the air from coughing or sneezing. It can also be spread if you touch something that has the droplets on it, and then touch your own nose, mouth or eyes. How bad is pneumococcal disease? Pneumococcal disease can be very bad for young children and is the most common cause of meningitis and bacterial pneumonia in children. How can pneumococcal disease be avoided in children? There is a vaccine that can help stop serious pneumococcal disease, such as meningitis and blood infections. -

Clostridioides Difficile As a Dynamic Vehicle for The

microorganisms Review Clostridioides difficile as a Dynamic Vehicle for the Dissemination of Antimicrobial-Resistance Determinants: Review and In Silico Analysis Philip Kartalidis 1, Anargyros Skoulakis 1, Katerina Tsilipounidaki 1 , Zoi Florou 1, Efthymia Petinaki 1 and George C. Fthenakis 2,* 1 Department of Clinical and Laboratory Research, Faculty of Medicine, School of Health Sciences, University of Thessaly, 41110 Larissa, Greece; [email protected] (P.K.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (K.T.); zoi_fl@hotmail.com (Z.F.); [email protected] (E.P.) 2 Veterinary Faculty, University of Thessaly, 43100 Karditsa, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The present paper is divided into two parts. The first part focuses on the role of Clostrid- ioides difficile in the accumulation of genes associated with antimicrobial resistance and then the transmission of them to other pathogenic bacteria occupying the same human intestinal niche. The second part describes an in silico analysis of the genomes of C. difficile available in GenBank, with regard to the presence of mobile genetic elements and antimicrobial resistance genes. The diversity of the C. difficile genome is discussed, and the current status of resistance of the organisms to various antimicrobial agents is reviewed. The role of transposons associated with antimicrobial resistance is Citation: Kartalidis, P.; Skoulakis, A.; appraised; the importance of plasmids associated with antimicrobial resistance is discussed, and the Tsilipounidaki, K.; Florou, Z.; significance of bacteriophages as a potential shuttle for antimicrobial resistance genes is presented. Petinaki, E.; Fthenakis, G.C. In the in silico study, 1101 C. difficile genomes were found to harbor mobile genetic elements; Tn6009, Clostridioides difficile as a Dynamic Tn6105, CTn7 and Tn6192, Tn6194 and IS256 were the ones more frequently identified. -

Transformation

BNL-71843-2003-BC The Ptieumococcus Editor : E. Tuomanen Associate Editors : B. Spratt, T. Mitchell, D. Morrison To be published by ASM Press, Washington. DC Chapter 9 Transformation Sanford A. Lacks* Biology Department Brookhaven National Laboratory Upton, NY 11973 Phone: 631-344-3369 Fax: 631-344-3407 E-mail: [email protected] Introduction Transformation, which alters the genetic makeup of an individual, is a concept that intrigues the human imagination. In Streptococcus pneumoniae such transformation was first demonstrated. Perhaps our fascination with genetics derived from our ancestors observing their own progeny, with its retention and assortment of parental traits, but such interest must have been accelerated after the dawn of agriculture. It was in pea plants that Gregor Mendel in the late 1800s examined inherited traits and found them to be determined by physical elements, or genes, passed from parents to progeny. In our day, the material basis of these genetic determinants was revealed to be DNA by the lowly bacteria, in particular, the pneumococcus. For this species, transformation by free DNA is a sexual process that enables cells to sport new combinations of genes and traits. Genetic transformation of the type found in S. pneumoniae occurs naturally in many species of bacteria (70), but, initially only a few other transformable species were found, namely, Haemophilus influenzae, Neisseria meningitides, Neisseria gonorrheae, and Bacillus subtilis (96). Natural transformation, which requires a set of genes evolved for the purpose, contrasts with artificial transformation, which is accomplished by shocking cells either electrically, as in electroporation, or by ionic and temperature shifts. Although such artificial treatments can introduce very small amounts of DNA into virtually any type of cell, the amounts introduced by natural transformation are a million-fold greater, and S.