Guidelines for Prevention and Control of Infection Due to Antibiotic Resistant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drug-Resistant Streptococcus Pneumoniae and Methicillin

NEWS & NOTES Conference Summary pneumoniae can vary among popula- conference sessions was that statically tions and is influenced by local pre- sound methods of data collection that Drug-resistant scribing practices and the prevalence capture valid, meaningful, and useful of resistant clones. Conference pre- data and meet the financial restric- Streptococcus senters discussed the role of surveil- tions of state budgets are indicated. pneumoniae and lance in raising awareness of the Active, population-based surveil- Methicillin- resistance problem and in monitoring lance for collecting relevant isolates is the effectiveness of prevention and considered the standard criterion. resistant control programs. National- and state- Unfortunately, this type of surveil- Staphylococcus level epidemiologists discussed the lance is labor-intensive and costly, aureus benefits of including state-level sur- making it an impractical choice for 1 veillance data with appropriate antibi- many states. The challenges of isolate Surveillance otic use programs designed to address collection, packaging and transport, The Centers for Disease Control the antibiotic prescribing practices of data collection, and analysis may and Prevention (CDC) convened a clinicians. The potential for local sur- place an unacceptable workload on conference on March 12–13, 2003, in veillance to provide information on laboratory and epidemiology person- Atlanta, Georgia, to discuss improv- the impact of a new pneumococcal nel. ing state-based surveillance of drug- vaccine for children was also exam- Epidemiologists from several state resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae ined; the vaccine has been shown to health departments that have elected (DRSP) and methicillin-resistant reduce infections caused by resistance to implement enhanced antimicrobial Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). -

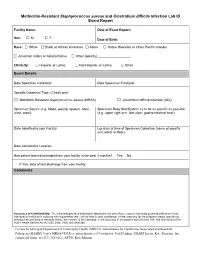

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus and Clostridium Difficile Infection Lab ID Event Report

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile Infection Lab ID Event Report Facility Name: Date of Event Report: Sex: M F □ □ Date of Birth: Race: □ White □ Black or African American □ Asian □ Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander □ American Indian or Alaska Native □ Other [specify] __________________ Ethnicity: □ Hispanic or Latino □ Not Hispanic or Latino □ Other Event Details Date Specimen Collected: Date Specimen Finalized: Specific Organism Type: (Check one) □ Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) □ Clostridium difficile Infection (CDI) Specimen Source (e.g. blood, wound, sputum, bone, Specimen Body Site/System try to be as specific as possible urine, stool): (e.g. upper right arm, foot ulcer, gastrointestinal tract): Date Admitted to your Facility: Location at time of Specimen Collection (name of specific unit, ward, or floor): Date Admitted to Location: Has patient been discharged from your facility in the past 3 months? Yes No If Yes, date of last discharge from your facility: Comments Assurance of Confidentiality: The voluntarily provided information obtained in this surveillance system that would permit identification of any individual or institution is collected with a guarantee that it will be held in strict confidence, will be used only for the purposes stated, and will not otherwise be disclosed or released without the consent of the individual, or the institution in accordance with Sections 304, 306 and 308(d) of the Public Health Service Act (42 USC 242b, 242k, and 242m(d)). For use by Michigan Department of Community Health (MDCH), Surveillance for Healthcare-Associated and Resistant Pathogens (SHARP) Unit’s MRSA/CDI Prevention Initiative (Coordinator: Gail Denkins, SHARP Intern: Kate Manton); fax completed forms to (517) 335-8263, ATTN: Kate Manton. -

Association Between Carriage of Streptococcus Pneumoniae and Staphylococcus Aureus in Children

BRIEF REPORT Association Between Carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus in Children Gili Regev-Yochay, MD Context Widespread pneumococcal conjugate vaccination may bring about epidemio- Ron Dagan, MD logic changes in upper respiratory tract flora of children. Of particular significance may Meir Raz, MD be an interaction between Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus, in view of the recent emergence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant S aureus. Yehuda Carmeli, MD, MPH Objective To examine the prevalence and risk factors of carriage of S pneumoniae Bracha Shainberg, PhD and S aureus in the prevaccination era in young children. Estela Derazne, MSc Design, Setting, and Patients Cross-sectional surveillance study of nasopharyn- geal carriage of S pneumoniae and nasal carriage of S aureus by 790 children aged 40 Galia Rahav, MD months or younger seen at primary care clinics in central Israel during February 2002. Ethan Rubinstein, MD Main Outcome Measures Carriage rates of S pneumoniae (by serotype) and S aureus; risk factors associated with carriage of each pathogen. TREPTOCOCCUS PNEUMONIAE AND Results Among 790 children screened, 43% carried S pneumoniae and 10% car- Staphylococcus aureus are com- ried S aureus. Staphylococcus aureus carriage among S pneumoniae carriers was 6.5% mon inhabitants of the upper vs 12.9% in S pneumoniae noncarriers. Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage among respiratory tract in children and S aureus carriers was 27.5% vs 44.8% in S aureus noncarriers. Only 2.8% carried both Sare responsible for common infec- pathogens concomitantly vs 4.3% expected dual carriage (P=.03). Risk factors for tions. Carriage of S aureus and S pneu- S pneumoniae carriage (attending day care, having young siblings, and age older than moniae can result in bacterial spread and 3 months) were negatively associated with S aureus carriage. -

Clostridium Difficile Infection: How to Deal with the Problem DH INFORMATION RE ADER B OX

Clostridium difficile infection: How to deal with the problem DH INFORMATION RE ADER B OX Policy Estates HR / Workforce Commissioning Management IM & T Planning / Finance Clinical Social Care / Partnership Working Document Purpose Best Practice Guidance Gateway Reference 9833 Title Clostridium difficile infection: How to deal with the problem Author DH and HPA Publication Date December 2008 Target Audience PCT CEs, NHS Trust CEs, SHA CEs, Care Trust CEs, Medical Directors, Directors of PH, Directors of Nursing, PCT PEC Chairs, NHS Trust Board Chairs, Special HA CEs, Directors of Infection Prevention and Control, Infection Control Teams, Health Protection Units, Chief Pharmacists Circulation List Description This guidance outlines newer evidence and approaches to delivering good infection control and environmental hygiene. It updates the 1994 guidance and takes into account a national framework for clinical governance which did not exist in 1994. Cross Ref N/A Superseded Docs Clostridium difficile Infection Prevention and Management (1994) Action Required CEs to consider with DIPCs and other colleagues Timing N/A Contact Details Healthcare Associated Infection and Antimicrobial Resistance Department of Health Room 528, Wellington House 133-155 Waterloo Road London SE1 8UG For Recipient's Use Front cover image: Clostridium difficile attached to intestinal cells. Reproduced courtesy of Dr Jan Hobot, Cardiff University School of Medicine. Clostridium difficile infection: How to deal with the problem Contents Foreword 1 Scope and purpose 2 Introduction 3 Why did CDI increase? 4 Approach to compiling the guidance 6 What is new in this guidance? 7 Core Guidance Key recommendations 9 Grading of recommendations 11 Summary of healthcare recommendations 12 1. -

Calves Infected with Virulent and Attenuated Mycoplasma Bovis Strains Have Upregulated Th17 Inflammatory and Th1 Protective Responses, Respectively

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Calves Infected with Virulent and Attenuated Mycoplasma bovis Strains Have Upregulated Th17 Inflammatory and Th1 Protective Responses, Respectively Jin Chao 1,2,3,4, Xiaoxiao Han 1,2, Kai Liu 1,2, Qingni Li 1,2, Qingjie Peng 5, Siyi Lu 1,2, Gang Zhao 1,2, Xifang Zhu 1,2, Guyue Hu 1,2, Yaqi Dong 1,2, Changmin Hu 2, Yingyu Chen 1,2, Jianguo Chen 2, Farhan Anwar Khan 1, Huanchun Chen 1,2,3,4 and Aizhen Guo 1,2,3,4,* 1 The State Key Laboratory of Agricultural Microbiology, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan 430070, China 2 College of Veterinary Medicine, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan 430070, China 3 Hubei International Scientific and Technological Cooperation Base of Veterinary Epidemiology, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan 430070, China 4 Key Laboratory of Development of Veterinary Diagnostic Products, Ministry of Agriculture, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan 430070, China 5 Wuhan Keqian Biology Ltd., Wuhan 430223, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-27-8728-6861 Received: 15 June 2019; Accepted: 27 August 2019; Published: 28 August 2019 Abstract: Mycoplasma bovis is a critical bovine pathogen, but its pathogenesis remains poorly understood. Here, the virulent HB0801 (P1) and attenuated HB0801-P150 (P150) strains of M. bovis were used to explore the potential pathogenesis and effect of induced immunity from calves’ differential transcriptomes post infection. Nine one-month-old male calves were infected with P1, P150, or mock-infected with medium and euthanized at 60 days post-infection. -

Role of Protein Phosphorylation in Mycoplasma Pneumoniae

Pathogenicity of a minimal organism: Role of protein phosphorylation in Mycoplasma pneumoniae Dissertation zur Erlangung des mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades „Doctor rerum naturalium“ der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen vorgelegt von Sebastian Schmidl aus Bad Hersfeld Göttingen 2010 Mitglieder des Betreuungsausschusses: Referent: Prof. Dr. Jörg Stülke Koreferent: PD Dr. Michael Hoppert Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 02.11.2010 “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” (Albert Einstein) Danksagung Zunächst möchte ich mich bei Prof. Dr. Jörg Stülke für die Ermöglichung dieser Doktorarbeit bedanken. Nicht zuletzt durch seine freundliche und engagierte Betreuung hat mir die Zeit viel Freude bereitet. Des Weiteren hat er mir alle Freiheiten zur Verwirklichung meiner eigenen Ideen gelassen, was ich sehr zu schätzen weiß. Für die Übernahme des Korreferates danke ich PD Dr. Michael Hoppert sowie Prof. Dr. Heinz Neumann, PD Dr. Boris Görke, PD Dr. Rolf Daniel und Prof. Dr. Botho Bowien für das Mitwirken im Thesis-Komitee. Der Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes gilt ein besonderer Dank für die finanzielle Unterstützung dieser Arbeit, durch die es mir unter anderem auch möglich war, an Tagungen in fernen Ländern teilzunehmen. Prof. Dr. Michael Hecker und der Gruppe von Dr. Dörte Becher (Universität Greifswald) danke ich für die freundliche Zusammenarbeit bei der Durchführung von zahlreichen Proteomics-Experimenten. Ein ganz besonderer Dank geht dabei an Katrin Gronau, die mich in die Feinheiten der 2D-Gelelektrophorese eingeführt hat. Außerdem möchte ich mich bei Andreas Otto für die zahlreichen Proteinidentifikationen in den letzten Monaten bedanken. Nicht zu vergessen ist auch meine zweite Außenstelle an der Universität in Barcelona. Dr. Maria Lluch-Senar und Dr. -

Dynamic Dashboard - List of Bacteria with a Relevant AMR Issue

14 May 2020 Dynamic Dashboard - List of bacteria with a relevant AMR issue Categorization and inclusion methodology for human bacterial pathogens The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Priority List of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria [1], the United States of America’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Antibiotic Resistant Threats in the United States 2019 [2] and the bacteria included in the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control’s (ECDC) European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) [3] were used to develop a combined list of priority bacteria with a drug-resistance issue. It was considered that all research into these bacteria, irrespective of the drug-resistance profile, would be relevant to advance efforts to address antimicrobial resistance. For the categorization process, only the bacterial genus level (noting the family Enterobacteriaceae was also included) was used and will be displayed. Table 1 list the genus included in categorization and the rules applied for inclusion based on the aforementioned priority lists. When projects included bacteria other than those listed in Table 1 an individual assessment was performed by the Secretariat to determine if there is a known drug-resistance issue. This assessment included searching the literature and reaching a consensus within the Secretariat if the bacteria has a known drug- resistance issue or not. Where consensus was not reached or there was ambiguity in the literature bacteria were parked and further investigation was conducted. The list of additional bacteria and the outcomes from the assessment are provided in Table 2 and 3. Please note that these lists will be continually updated. -

DCMC Community Acquired Pneumonia Discussion and Review

DELL CHILDREN’S MEDICAL CENTER EVIDENCE-BASED OUTCOMES CENTER ADDENDUM 3 Discussion and Review of the Evidence Contents 1 Etiology ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Streptococcus pneumoniae ....................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Mycoplasma pneumoniae ......................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Haemophilus influenzae ........................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Streptococcus pyogenes ........................................................................................................................... 2 1.5 Staphylococcus aureus ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.6 Viruses ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.7 Underimmunized patients ........................................................................................................................ 3 2 Diagnostic Evaluation ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 History ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA)

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) Over the past several decades, the incidence of resistant gram-positive organisms has risen in the United States. MRSA strains, first identified in the 1960s in England, were first observed in the U.S. in the mid 1980s.1 Resistance quickly developed, increasing from 2.4% in 1979 to 29% in 1991.2 The current prevalence for MRSA in hospitals and other facilities ranges from <10% to 65%. In 1999, MRSA accounted for more than 50% of all Staphylococcus aureus isolates within U.S. intensive care units.3, 4 The past years, however, outbreaks of MRSA have also been seen in the community setting, particularly among preschool-age children, some of whom have attended day-care centers.5, 6, 7 MRSA does not appear to be more virulent than methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, but certainly poses a greater treatment challenge. MRSA also has been associated with higher hospital costs and mortality.8 Within a decade of its development, methicillin resistance to Staphylococcus aureus emerged.9 MRSA strains generally are now resistant to other antimicrobial classes including aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, carbapenems, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and macrolides.10,11 Most of the resistance was secondary to production of beta-lactamase enzymes or intrinsic resistance with alterations in penicillin-binding proteins. Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequent cause of nosocomial pneumonia and surgical- wound infections and the second most common cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections.12 Long-term care facilities (LTCFs) have developed rates of MRSA ranging from 25%-35%. MRSA rates may be higher in LTCFs if they are associated with hospitals that have higher rates.13 Transmission of MRSA generally occurs through direct or indirect contact with a reservoir. -

Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA)

Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Clostridium difficile and ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in the home and community: assessing the problem, controlling the spread An expert report commissioned by the International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene © International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene, 2006 2 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 4 SUMMARY 5 1. INTRODUCTION – INFECTIOUS DISEASE AND HYGIENE IN THE 21ST CENTURY 7 2. THE CHAIN OF INFECTION TRANSMISSION IN THE HOME 10 3. METHICILLIN RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS (MRSA) 11 3.1 CHARACTERISTICS OF STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS AND METHICILLIN RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS 11 3.2 HOSPITAL-ACQUIRED, HEALTHCARE ASSOCIATED AND COMMUNITY ACQUIRED MRSA 11 3.3 UNDERSTANDING THE CHAIN OF INFECTION FOR S. AUREUS AND MRSA IN THE HOME 13 3.4 WHAT ARE THE RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH S. AUREUS AND MRSA IN THE COMMUNITY? 22 4. CLOSTRIDIUM DIFFICILE 24 4.1 CHARACTERISTICS OF CLOSTRIDIUM DIFFICILE 24 4.2 HOSPITAL-ACQUIRED AND COMMUNITY- ACQUIRED C. DIFFICILE 24 4.3 UNDERSTANDING THE CHAIN OF INFECTION FOR C. DIFFICILE IN THE HOME 25 4.4 WHAT ARE THE RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH C. DIFFICILE IN THE HOME AND COMMUNITY 28 5. EXTENDED-SPECTRUM ß-LACTAMASE ESCHERICHIA COLI (ESBLS) 30 5.1 CHARACTERISTICS OF ESCHERICHIA COLI 30 5.2 HOSPITAL AND COMMUNITY-ACQUIRED ESBL-PRODUCING E. COLI INFECTIONS 31 5.3 UNDERSTANDING THE CHAIN OF INFECTION FOR E. COLI AND ESBL-PRODUCING E. COLI IN THE HOME 31 5.4 RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH ESBLS IN THE COMMUNITY 33 6. REDUCING THE RISKS OF TRANSMISSION OF METHICILLIN RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS (MRSA), CLOSTRIDIUM DIFFICILE AND ESBL-PRODUCING ESCHERICHIA COLI IN THE HOME AND COMMUNITY - DEVELOPING A RISK-BASED APPROACH TO HOME HYGIENE 35 6.1 BREAKING THE CHAIN OF TRANSMISSION OF INFECTION IN THE HOME 35 6.2 DEVELOPING A RISK-BASED APPROACH TO HOME HYGIENE 35 6.3 INTERRUPTING THE CHAIN OF INFECTION TRANSMISSION IN THE HOME 38 7. -

Safety and Efficacy of Ceftaroline Fosamil in the Management of Community-Acquired Bacterial Pneumonia Heather F

Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine DigitalCommons@PCOM PCOM Scholarly Papers 2014 Safety and Efficacy of Ceftaroline Fosamil in the Management of Community-Acquired Bacterial Pneumonia Heather F. DeBellis Kimberly L. Barefield Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pcom.edu/scholarly_papers Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation DeBellis, Heather F. and Barefield, Kimberly L., "Safety and Efficacy of Ceftaroline Fosamil in the Management of Community- Acquired Bacterial Pneumonia" (2014). PCOM Scholarly Papers. 1913. https://digitalcommons.pcom.edu/scholarly_papers/1913 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@PCOM. It has been accepted for inclusion in PCOM Scholarly Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@PCOM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Open Access: Full open access to Clinical Medicine Reviews this and thousands of other papers at http://www.la-press.com. in Therapeutics Safety and Efficacy of Ceftaroline Fosamil in the Management of Community- Acquired Bacterial Pneumonia Heather F. DeBellis and Kimberly L. Tackett South University School of Pharmacy, Savannah, GA, USA. ABSTR ACT: Ceftaroline fosamil is a new fifth-generation cephalosporin indicated for the treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP). It possesses antimicrobial effects against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), but not against anaerobes. Organisms covered by this novel agent that are commonly associated with CABP are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Klebsiella pneumoniae; however, ceftaroline fosamil lacks antimicrobial activity against Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter species. -

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Threat Level Serious

METHICILLIN-RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS THREAT LEVEL SERIOUS 323,700 10,600 $1.7B Estimated cases Estimated Estimated attributable in hospitalized deaths in 2017 healthcare costs in 2017 patients in 2017 Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) are common bacteria that spread in healthcare facilities and the community. Methicillin- resistant S. aureus (MRSA) can cause difficult-to-treat staph infections because of resistance to some antibiotics. WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW CASES OVER TIME ■ Although several treatments are still available, MRSA Cases represented do not include the many skin infections that has become resistant to many first-line antibiotics. happen, but are not cultured and diagnosed. ■ While MRSA infections overall are dropping, progress 500,000 to prevent MRSA bloodstream infections in healthcare 401,000 is slowing. 400,000 391,000 365,400 359,500 ■ People who inject drugs are 16 times more likely to 343,100 323,700 develop a serious (invasive) MRSA infection than those 300,000 who do not. 200,000 100,000 Estimated Cases of MRSA in Hospitalized Patients in Hospitalized Cases of MRSA Estimated 0 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 30 25 An estimated 7% decline each year 20 15 10 An estimated 17% decline each year from 2005 to 2016, and no change from 2013 to 2016 5 Estimated Cases of MRSA Per 100,000 People 100,000 Per Cases of MRSA Estimated 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Community-onset MRSA Bloodstream Infection Rate Hospital-onset MRSA Bloodstream Infection Rate 500,000 401,000 400,000 391,000 365,400 359,500 343,100 323,700 300,000 METHICILLIN-RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS200,000 (MRSA) MRSA INFECTIONS CAN BE PREVENTED REDUCTIONS100,000 IN HOSPITALS HAVE STALLED MRSA infections are preventable and many lives have been New Patients in Hospitalized Cases of MRSA Estimated strategies in healthcare, along with current CDC 0 saved through effective infection control interventions.