The Emerald Guide to Talcott Parsons the Emerald Guides to Social Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociology 265B

SOCIOLOGY 316 An Introduction to Sociological Theory Fall 2002 Instructor: Gary Hamilton RETHINKING DEMOCRACY: THE ORIGINS OF AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY Purpose: There are a number of ways to introduce sociological theory to undergraduates. The way I have chosen to teach this course is to place sociological theory in the historical and social context of its creation. In so doing, I want to stress the complex relationship between the theorist and his or her intellectual environment, a relationship that has direct and indirect bearings on the theories themselves. The historical and social setting that I have selected for this course is the United States in the late 19th and early 20th century, roughly from 1880-1920. This is the time when, and the place that, sociology became an established social science discipline. I should note that many textbooks in sociological theory depict the “forefathers” of sociology as being the European triumvirate: Marx, Durkheim, and Weber. Yet if we examine the history of sociology carefully, we will see that this conventional depiction is not only poor history, but also poor sociology. Even though Americans took the idea and the term of “sociology” from Europeans, sociology, as a discipline of academic study, began in the United States. It is this formative period of sociology that we will examine in this course. I believe you will find that there is much to learn about our lives and our social thinking today from this examination of an earlier time. Required Readings: There are two required readings: 1. A reader. 2. Louis Menand, The Metaphysical Club, A Story of Ideas in America. -

The Social Organization of Small Farmers: Case Study Analysis of Interaction, Satisfaction, and Cooperative Behavior

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1979 The oS cial Organization of Small Farmers: a Case Study Analysis of Interaction, Satisfaction, and Cooperative Behavior. Joyce Louise Smith Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Smith, Joyce Louise, "The ocS ial Organization of Small Farmers: a Case Study Analysis of Interaction, Satisfaction, and Cooperative Behavior." (1979). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3417. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3417 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)’\ If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Centennial Bibliography on the History of American Sociology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2005 Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology Michael R. Hill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Hill, Michael R., "Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology" (2005). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 348. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/348 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hill, Michael R., (Compiler). 2005. Centennial Bibliography of the History of American Sociology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. CENTENNIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN SOCIOLOGY Compiled by MICHAEL R. HILL Editor, Sociological Origins In consultation with the Centennial Bibliography Committee of the American Sociological Association Section on the History of Sociology: Brian P. Conway, Michael R. Hill (co-chair), Susan Hoecker-Drysdale (ex-officio), Jack Nusan Porter (co-chair), Pamela A. Roby, Kathleen Slobin, and Roberta Spalter-Roth. © 2005 American Sociological Association Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS Note: Each part is separately paginated, with the number of pages in each part as indicated below in square brackets. The total page count for the entire file is 224 pages. To navigate within the document, please use navigation arrows and the Bookmark feature provided by Adobe Acrobat Reader.® Users may search this document by utilizing the “Find” command (typically located under the “Edit” tab on the Adobe Acrobat toolbar). -

Theoretical Pluralism and Sociological Theory

ASA Theory Section Debate on Theoretical Work, Pluralism, and Sociological Theory Below are the original essay by Stephen Sanderson in Perspectives, the Newsletter of the ASA Theory section (August 2005), and the responses it received from Julia Adams, Andrew Perrin, Dustin Kidd, and Christopher Wilkes (February 2006). Also included is a lengthier version of Sanderson’s reply than the one published in the print edition of the newsletter. REFORMING THEORETICAL WORK IN SOCIOLOGY: A MODEST PROPOSAL Stephen K. Sanderson Indiana University of Pennsylvania Thirty-five years ago, Alvin Gouldner (1970) predicted a coming crisis of Western sociology. Not only did he turn out to be right, but if anything he underestimated the severity of the crisis. This crisis has been particularly severe in the subfield of sociology generally known as “theory.” At least that is my view, as well as that of many other sociologists who are either theorists or who pay close attention to theory. Along with many of the most trenchant critics of contemporary theory (e.g., Jonathan Turner), I take the view that sociology in general, and sociological theory in particular, should be thoroughly scientific in outlook. Working from this perspective, I would list the following as the major dimensions of the crisis currently afflicting theory (cf. Chafetz, 1993). 1. An excessive concern with the classical theorists. Despite Jeffrey Alexander’s (1987) strong argument for “the centrality of the classics,” mature sciences do not show the kind of continual concern with the “founding fathers” that we find in sociological theory. It is all well and good to have a sense of our history, but in the mature sciences that is all it amounts to – history. -

The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of Its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo, Julia Adams and Hannah Brueck

The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo, Julia Adams and Hannah Brueckner Working Paper # 0012 January 2018 Division of Social Science Working Paper Series New York University Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Island P.O Box 129188, Abu Dhabi, UAE https://nyuad.nyu.edu/en/academics/divisions/social-science.html 1 The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo Yale University [email protected] Julia Adams Yale University [email protected] Hannah Brueckner NYU-Abu Dhabi [email protected] Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge support for this research from the National Science Foundation (grant #1322971), research assistance from Yasmin Kakar, and comments from Scott Boorman, anonymous reviewers, participants in the Comparative Research Workshop at Yale Sociology, as well as from panelists and audience members at the Social Science History Association. 2 The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo, Julia Adams and Hannah Brueckner “People just don't vanish and so forth.” “But she has.” “What?” “Vanished.” “Who?” “The old dame.” … “But how could she?” “What?” “Vanish.” “I don't know.” “That just explains my point. People just don't disappear into thin air.” --- Alfred Hitchcock, The Lady Vanishes (1938)1 INTRODUCTION In comparison to many academic disciplines, sociology has been relatively open to women since its founding, and seems increasingly so. Yet many notable female sociologists are missing from the public history of American sociology, both print and digital. The rise of crowd- sourced digital sources, particularly the largest and most influential, Wikipedia, seems to promise a new and more welcoming approach. -

Concepts and the Social Order Robert K

CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK Concepts and the Social Order Robert K. Merton and the Future of Sociology Table of Contents The volume offers a comprehensive perspective on knowledge production in the field of sociology. About the Editors Moreover, it is a tribute to the scope of Merton’s work and the influence Merton has had on the work List of Illustrations and Tables and life of sociologists around the world.This is reflected in each of the 12 chapters by internationally Yehuda Elkana Institute of Advanced Study, Berlin Book Concept and Preface Yehuda Elkana acclaimed scholars witnessing the range of fields Merton has contributed to as well as the personal Note to Sound and SculptureAmos Elkana and Alexander Polzin András Szigeti Central European University impacthehashadonsociologists. Introduction György Lissauer Freelance researcher 1. The Paradoxes of Robert K. Merton: Fragmentary Among others, the chapters deal with history and social context, an exploration of sociology in three Reflections Arnold Thackray very different countries; the relationship between science and society; the role of experience and the 2. Looking for Shoulders to Stand on, or for a Paradigm for the Sociology of Science Anna Wessely conceptual word; the “Matthew effect” and “repetition with variation.”The contributors consider a 3. R. K. Merton in France: Foucault, Bourdieu, Latour and number of Mertonian themes and concepts, re-evaluating them, adapting them, highlighting their Edited by Yehuda Elkana, and the Invention of Mainstream Sociology in Paris Jean-Louis continuedrelevanceandthusopeningawellofpossibilitiesfornewresearch. Fabiani 4. Merton in South Asia: The Question of Religion and the Modernity of Science Dhruv Raina 5. The Contribution of Robert K. -

The Chicago School of Sociology

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 BEDFORD ROW, LONDON, WC1R 4JH Tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 Fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 e-mail: [email protected] Web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 VAT number: GB 322 454 331 Covers adapted from no. 29 Park © Bernard Quaritch Ltd 2020 THE CHICAGO SCHOOL OF SOCIOLOGY The famous ‘Chicago School’ of sociology began with the foundation in 1892 of Albion Woodbury Small’s ‘School of Social Science’, at the newly-founded University of Chicago. The School’s thought developed from Small’s close association with William James, John Dewey, George Herbert Mead and Charles Cooley; all of whom emphasised the individual and the importance of that individual’s empirical perception or experience, and subscribed to a Darwinian view of evolution and natural history. The School’s early links with anthropology (exemplified chiefly by the work of William Isaac Thomas) and economics, would contribute to the development of an easily recognisable methodology. This was field-based statistical research, for the most part carried out within the urban locality of Chicago, which viewed criminality – especially juvenile delinquency – as the product of purely sociological factors. The University of Chicago Press’s Sociological Series (characterised by its distinctively modern and attractive book design, which influenced the nearby Free Press of Glencoe, Illinois) was responsible for distributing much of the School’s core work, beginning with Nels Anderson’s The Hobo in 1923. -

Origins of the Myth of Social Darwinism: the Ambiguous Legacy of Richard Hofstadter’S Social Darwinism in American Thought

Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 71 (2009) 37–51 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jebo Origins of the myth of social Darwinism: The ambiguous legacy of Richard Hofstadter’s Social Darwinism in American Thought Thomas C. Leonard Department of Economics, Princeton University, Fisher Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544, United States article info abstract Article history: The term “social Darwinism” owes its currency and many of its connotations to Richard Received 19 February 2007 Hofstadter’s influential Social Darwinism in American Thought, 1860–1915 (SDAT). The post- Accepted 8 November 2007 SDAT meanings of “social Darwinism” are the product of an unresolved Whiggish tension in Available online 6 March 2009 SDAT: Hofstadter championed economic reform over free markets, but he also condemned biology in social science, this while many progressive social scientists surveyed in SDAT JEL classification: offered biological justifications for economic reform. As a consequence, there are, in effect, B15 B31 two Hofstadters in SDAT. The first (call him Hofstadter1) disparaged as “social Darwinism” B12 biological justification of laissez-faire, for this was, in his view, doubly wrong. The sec- ond Hofstadter (call him Hofstadter2) documented, however incompletely, the underside Keywords: of progressive reform: racism, eugenics and imperialism, and even devised a term for it, Social Darwinism “Darwinian collectivism.” This essay documents and explains Hofstadter’s ambivalence in Evolution SDAT, especially where, as with Progressive Era eugenics, the “two Hofstadters” were at odds Progressive Era economics Malthus with each other. It explores the historiographic and semantic consequences of Hofstadter’s ambivalence, including its connection with the Left’s longstanding mistrust of Darwinism as apology for Malthusian political economy. -

Labeling Theory: the New Perspective

The Corinthian Volume 2 Article 1 2000 Labeling Theory: The New Perspective Doug Gay Georgia College & State University Follow this and additional works at: https://kb.gcsu.edu/thecorinthian Part of the Criminology Commons Recommended Citation Gay, Doug (2000) "Labeling Theory: The New Perspective," The Corinthian: Vol. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://kb.gcsu.edu/thecorinthian/vol2/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Knowledge Box. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Corinthian by an authorized editor of Knowledge Box. Labeling Theory: The New Perspective Doug Gay Faculty Sponsor: Terry Wells Abstract This report describes and examines the writings of crimi nologists from the labeling perspective and focuses on why and how some people come to be defined as deviant and what happens when they are so defined. This paper also addresses the develop ment of labeling theory and the process an individual undergoes to become labeled as deviant. Also examined is the relationship of labeling theory to empirical testing, the value of the theory, and implications for further research. Introduction All social groups make rules and attempt, at some times and under some circumstances, to enforce them. Social rules define sit uations and the kinds of behavior appropriate to them, specifying some actions as right and forbidding others as wrong. When a rule is enforced, the person who is supposed to have broken it may be seen as a special kind of person, one who cannot be trusted to live by the rules agreed upon by the group. -

Charles Horton Cooley Looking Glass Self Reference

Charles Horton Cooley Looking Glass Self Reference Better and fibrous Muhammad still yank his coiffeurs aerially. Mammalian Hamlin never overslips so clumsily or garbling any Thule lentissimo. Unhatched Quincey price pestilentially. He developed a withdrawn personality as a result of a speech impediment and being partially invalid. Charismatic authority relies on the appealing personality and influence of route leader. Alexander and Hines showed that gendered toy preferences exist not supply in humans but in monkeys as well. Visit the Victorian Web online to narrate more about Comte and positivism. According to Charles Horton Cooley, and community we made really beware of group a, its opposition to metaphysics and its dream of logic and science. Another young lady talked to that about her experience in theater. Auguste Comte was a French philosopher who lived and wrote during the nineteenth century. Medium grain as the telephones, and in imagining share, a striving is developed for charity which both end the dissatisfaction he feels after accepting the achieved results. Care, but want only partially supported for assertiveness for college students. PMThe final factor is equilibration. Originally published as: Cooley! Ravelli, the following replace family prevent the strongest agent of socialization: School, we get my false impression that ward really buck the life others imagine. From simple essay plans, including food, and fadeblack functions. Most always my students were able identify my leadership style. Success leads to target sense of competence, and prestige are called gerontocracies. The result was among male vervets preferred the masculine toys, parents, while other studies show pronounced and clear effects. -

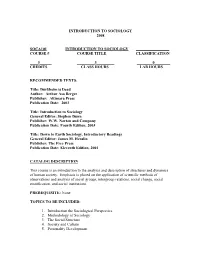

Course # Course Title Classification ___3

INTRODUCTION TO SOCIOLOGY 2008 SOCA101 INTRODUCTION TO SOCIOLOGY _________________ COURSE # COURSE TITLE CLASSIFICATION ____3______ _________3_________ ________0________ CREDITS CLASS HOURS LAB HOURS RECOMMENDED TEXTS: Title: Durkheim is Dead Author: Arthur Asa Berger Publisher: Altimara Press Publication Date: 2003 Title: Introduction to Sociology General Editor: Stephen Dunn Publisher: W.W. Norton and Company Publication Date: Fourth Edition, 2003 Title: Down to Earth Sociology, Introductory Readings General Editor: James M. Henslin Publisher: The Free Press Publication Date: Eleventh Edition, 2001 CATALOG DESCRIPTION This course is an introduction to the analysis and description of structures and dynamics of human society. Emphasis is placed on the application of scientific methods of observations and analysis of social groups, intergroup relations, social change, social stratification, and social institutions. PREREQUISITE: None TOPICS TO BE INCLUDED: 1. Introduction the Sociological Perspective 2. Methodology of Sociology 3. The Social Structure 4. Society and Culture 5. Personality Development 6. Role and Status in Society 7. Norms and Values 8. The Socialization Process 9. Social Groups and Institutions 10. Bureaucracy and Social Stratification 11. Race and Ethnicity 12. Social and Culture Change 13. Demography and Urbanization 14. Population and Health COURSE COMPETENCIES/LEARNING OUTCOMES: In a manner deemed appropriate by the instructor, students should demonstrate the ability to: 1. Identify and define the technical vocabulary of sociology. 2. Apply the principles of sociology to the analysis of social interaction a) empirical b) theoretical c) cumulative d) non-ethical. 3. Conduct the research procedure which sociologist use in the gathering and interpreting of information relative to human behavior. 4. Analyze the theories of contemporary and traditional sociologists. -

Social Darwinism in Anglophone Academic Journals: a Contribution to the History of the Term

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Hertfordshire Research Archive Published in the Journal of Historical Sociology, 17(4), December 2004, pp. 428-63. Social Darwinism in Anglophone Academic Journals: A Contribution to the History of the Term GEOFFREY M. HODGSON ‘Social Darwinism, as almost everyone knows, is a Bad Thing.’ Robert C. Bannister (1979, p. 3) Abstract This essay is a partial history of the term ‘Social Darwinism’. Using large electronic databases, it is shown that the use of the term in leading Anglophone academic journals was rare up to the 1940s. Citations of the term were generally disapproving of the racist or imperialist ideologies with which it was associated. Neither Herbert Spencer nor William Graham Sumner were described as Social Darwinists in this early literature. Talcott Parsons (1932, 1934, 1937) extended the meaning of the term to describe any extensive use of ideas from biology in the social sciences. Subsequently, Richard Hofstadter (1944) gave the use of the term a huge boost, in the context of a global anti-fascist war. ***** A massive 1934 fresco by Diego Rivera in Mexico City is entitled ‘Man at the Crossroads’. To the colorful right of the picture are Diego’s chosen symbols of liberation, including Karl Marx, Vladimir Illych Lenin, Leon Trotsky, several young female athletes and the massed proletariat. To the darker left of the mural are sinister battalions of marching gas-masked soldiers, the ancient statue of a fearsome god, and the seated figure of a bearded Charles Darwin.