Labeling Theory: the New Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations NCSS Strands: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions Time, Continuity, and Change Grade level: 9-12 Class periods needed: 1.5- 50 minute periods Purpose, Background, and Context Sociologists seek to understand how and why deviance occurs within a society. They do this by developing theories that explain factors impacting deviance on a wide scale such as social frustrations, socialization, social learning, and the impact of labeling. Four main theories have developed in the last 50 years. Anomie: Deviance is caused by anomie, or the feeling that society’s goals or the means to achieve them are closed to the person Control: Deviance exists because of improper socialization, which results in a lack of self-control for the person Differential association: People learn deviance from associating with others who act in deviant ways Labeling: Deviant behavior depends on who is defining it, and the people in our society who define deviance are usually those in positions of power Students will participate in a “jigsaw” where they will become knowledgeable in one theory and then share their knowledge with the rest of the class. After all theories have been presented, the class will use the theories to explain an historic example of socially deviant behavior: Zoot Suit Riots. Objectives & Student Outcomes Students will: Be able to define the concepts of social norms and deviance 1 Brainstorm behaviors that fit along a continuum from informal to formal deviance Learn four sociological theories of deviance by reading, listening, constructing hypotheticals, and questioning classmates Apply theories of deviance to Zoot Suit Riots that occurred in the 1943 Examine the role of social norms for individuals, groups, and institutions and how they are reinforced to maintain a order within a society; examine disorder/deviance within a society (NCSS Standards, p. -

Children of Organized Crime Offenders: Like Father, Like Child?

Eur J Crim Policy Res https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-018-9381-6 Children of Organized Crime Offenders: Like Father, Like Child? An Explorative and Qualitative Study Into Mechanisms of Intergenerational (Dis)Continuity in Organized Crime Families Meintje van Dijk1 & Edward Kleemans1 & Veroni Eichelsheim 2 # The Author(s) 2018 Abstract This qualitative descriptive study aims to explore (1) the extent of intergenerational continuity of crime in families of organized crime offenders, (2) the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon and (3) the mechanisms underlying intergenerational discontinuity. The study comprised a descriptive analysis of the available numeric information on 25 organized crime offenders based in Amsterdam and their 48 children of at least 19 years of age and a more qualitative in-depth analysis of police files, justice department files and child protection service files of all the family members of 14 of the 25 families. Additionally, interviews with employees of the involved organizations were conducted. In terms of prevalence in official record crime statistics, the results show that a large majority of the organized crime offenders’ sons seem to follow in their fathers’ footsteps. This is not the case for daughters, as half of them have a criminal record, but primarily for only one minor crime. Intergenerational transmission seems to be facilitated by mediating risk factors, inadequate parenting skills of the mother, the Bfamous^ or violent reputation of the father, and deviant social learning. If we want to break the intergenerational chain of crime and violence, the results seem to suggest that an accumulation of protective factors seem to be effective, particularly for girls. -

Passivity: Looking at Bystanding Through the Lens of Criminological Theory

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2011 Passivity: Looking at Bystanding Through the Lens of Criminological Theory Rahim Manji [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Civic and Community Engagement Commons, and the Criminology Commons Recommended Citation Manji, Rahim, "Passivity: Looking at Bystanding Through the Lens of Criminological Theory. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2011. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/897 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Rahim Manji entitled "Passivity: Looking at Bystanding Through the Lens of Criminological Theory." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Sociology. Lois Presser, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Harry Dahms, Ben Feldmeyer Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Passivity: Looking at Bystanding Through the Lens of Criminological Theory A Thesis Presented for the Masters of Arts Degree University of Tennessee, Knoxville Rahim Manji May, 2011 To the idea of a world in which injustice causes people to roil. -

The Social Organization of Small Farmers: Case Study Analysis of Interaction, Satisfaction, and Cooperative Behavior

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1979 The oS cial Organization of Small Farmers: a Case Study Analysis of Interaction, Satisfaction, and Cooperative Behavior. Joyce Louise Smith Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Smith, Joyce Louise, "The ocS ial Organization of Small Farmers: a Case Study Analysis of Interaction, Satisfaction, and Cooperative Behavior." (1979). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3417. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3417 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)’\ If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Anarchy! an Anthology of Emma Goldman's Mother Earth

U.S. $22.95 Political Science anarchy ! Anarchy! An Anthology of Emma Goldman’s MOTHER EARTH (1906–1918) is the first An A n t hol o g y collection of work drawn from the pages of the foremost anarchist journal published in America—provocative writings by Goldman, Margaret Sanger, Peter Kropotkin, Alexander Berkman, and dozens of other radical thinkers of the early twentieth cen- tury. For this expanded edition, editor Peter Glassgold contributes a new preface that offers historical grounding to many of today’s political movements, from liber- tarianism on the right to Occupy! actions on the left, as well as adding a substantial section, “The Trial and Conviction of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman,” which includes a transcription of their eloquent and moving self-defense prior to their imprisonment and deportation on trumped-up charges of wartime espionage. of E m m A g ol dm A n’s Mot h er ea rt h “An indispensable book . a judicious, lively, and enlightening work.” —Paul Avrich, author of Anarchist Voices “Peter Glassgold has done a great service to the activist spirit by returning to print Mother Earth’s often stirring, always illuminating essays.” —Alix Kates Shulman, author of Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen “It is wonderful to have this collection of pieces from the days when anarchism was an ism— and so heady a brew that the government had to resort to illegal repression to squelch it. What’s more, it is still a heady brew.” —Kirkpatrick Sale, author of The Dwellers in the Land “Glassgold opens with an excellent brief history of the publication. -

The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of Its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo, Julia Adams and Hannah Brueck

The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo, Julia Adams and Hannah Brueckner Working Paper # 0012 January 2018 Division of Social Science Working Paper Series New York University Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Island P.O Box 129188, Abu Dhabi, UAE https://nyuad.nyu.edu/en/academics/divisions/social-science.html 1 The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo Yale University [email protected] Julia Adams Yale University [email protected] Hannah Brueckner NYU-Abu Dhabi [email protected] Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge support for this research from the National Science Foundation (grant #1322971), research assistance from Yasmin Kakar, and comments from Scott Boorman, anonymous reviewers, participants in the Comparative Research Workshop at Yale Sociology, as well as from panelists and audience members at the Social Science History Association. 2 The Ladies Vanish? American Sociology and the Genealogy of its Missing Women on Wikipedia Wei Luo, Julia Adams and Hannah Brueckner “People just don't vanish and so forth.” “But she has.” “What?” “Vanished.” “Who?” “The old dame.” … “But how could she?” “What?” “Vanish.” “I don't know.” “That just explains my point. People just don't disappear into thin air.” --- Alfred Hitchcock, The Lady Vanishes (1938)1 INTRODUCTION In comparison to many academic disciplines, sociology has been relatively open to women since its founding, and seems increasingly so. Yet many notable female sociologists are missing from the public history of American sociology, both print and digital. The rise of crowd- sourced digital sources, particularly the largest and most influential, Wikipedia, seems to promise a new and more welcoming approach. -

Concepts and the Social Order Robert K

CYAN MAGENTA YELLOW BLACK Concepts and the Social Order Robert K. Merton and the Future of Sociology Table of Contents The volume offers a comprehensive perspective on knowledge production in the field of sociology. About the Editors Moreover, it is a tribute to the scope of Merton’s work and the influence Merton has had on the work List of Illustrations and Tables and life of sociologists around the world.This is reflected in each of the 12 chapters by internationally Yehuda Elkana Institute of Advanced Study, Berlin Book Concept and Preface Yehuda Elkana acclaimed scholars witnessing the range of fields Merton has contributed to as well as the personal Note to Sound and SculptureAmos Elkana and Alexander Polzin András Szigeti Central European University impacthehashadonsociologists. Introduction György Lissauer Freelance researcher 1. The Paradoxes of Robert K. Merton: Fragmentary Among others, the chapters deal with history and social context, an exploration of sociology in three Reflections Arnold Thackray very different countries; the relationship between science and society; the role of experience and the 2. Looking for Shoulders to Stand on, or for a Paradigm for the Sociology of Science Anna Wessely conceptual word; the “Matthew effect” and “repetition with variation.”The contributors consider a 3. R. K. Merton in France: Foucault, Bourdieu, Latour and number of Mertonian themes and concepts, re-evaluating them, adapting them, highlighting their Edited by Yehuda Elkana, and the Invention of Mainstream Sociology in Paris Jean-Louis continuedrelevanceandthusopeningawellofpossibilitiesfornewresearch. Fabiani 4. Merton in South Asia: The Question of Religion and the Modernity of Science Dhruv Raina 5. The Contribution of Robert K. -

Industrial and Labor Relations

Cornell University ANNOUNCEMENTS New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations 1970-71 A Statutory College of the State University, At Cornell University, Ithaca, New York CORNELL UNIVERSITY ANNOUNCEMENTS Volume 61. N um ber 8. Septem ber 17, 1969. Published twenty-three times a year: five times in October; four times in August; three times in March; twice in May, July, September, and November; and once in January, June, and December. Published by Cornell University at Shel don Court, 420 College Avenue, Ithaca, New York 14850. Second-class postage paid at Ithaca. Cornell University New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations 1970-71 A Statutory College of the State University, At Cornell University, Ithaca, New York Cornell Academic Calendar 1969-70* Registration, new students Th, Sept. 1 1 Registration, old students F, Sept. 12 Fall term instruction begins, 7:30 a .m . M, Sept. 15 Midterm grade reports due S, Oct. 25 Thanksgiving recess: Instruction suspended, 1:10 p . m . W, Nov. 26 Instruction resumed, 7:30 a . m . M, Dec. 1 Fall term instruction ends, 1:10 p.m. S, Dec. 20 Christmas recess Independent study period begins M, Jan . 5 Final examinations begin M, Jan. 12 Final examinations end T , Jan. 20 Intersession begins \V, Jan . 21 Registration, new students T h,J an. 29 Registration, old students F, Jan. 30 Spring term instruction begins, 7:30 a . m . M, Feb. 2 Deadline: changed or make-up grades M, Feb. 9 Midterm grade reports due S, Mar. 14 Spring recess: Instruction suspended, 1:10 p .m . -

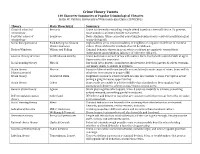

Article Title Labeling Theory Anomie Theory Gun Spree at Columbine High

Article Title Labeling Theory Anomie Theory "Urgent need for concerted action by Congress, Gun Spree at Columbine High "trench coat mafia" state legislators, and gun manufacturers..." "Jocks, brains, burnouts, and goths, the black-clad Though Far from Colorado, One High "Now you have to worry even more, who you demimonde to which Mr. school is Feeling a Sense of the Terror can and can't be friends with" Harris and Mr. Dylan apparently belonged." "trench coat mafia" Letter to the Editor 3-No title "potential troublemakers" "I saw fire alarms had gone off, kids exiting the building, teachers helping kids A Principal's Grief out of the building" "Why were the 15 killed? Why? Life is so unfair." "the incident set off a national bout of soul "members of a self-styled searching and debates over...guns or by the group of loners and outcasts" violent images on television and in video games" "I can't even imagine walking into that school "trench coat mafia" right now...I don't think I ever want to set foot 2 Are Suspects; Delay Caused in there again" By Explosives "many parents say they moved to enroll their "popular students whom they students in good and safe public schools, grief referred to as jocks" and shock were pervasive" "largest school massacre by students in the country's "repercussions were felt far beyond Colorado" history" "two troubled, suicidal killers" "School Security"; "Early Intervention"; The Scourge of School Violence "Gun Control" "troubled students" "trench coat mafia" "trench-coat-clad student" Authorities Find a Large -

The Chicago School of Sociology

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 BEDFORD ROW, LONDON, WC1R 4JH Tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 Fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 e-mail: [email protected] Web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 VAT number: GB 322 454 331 Covers adapted from no. 29 Park © Bernard Quaritch Ltd 2020 THE CHICAGO SCHOOL OF SOCIOLOGY The famous ‘Chicago School’ of sociology began with the foundation in 1892 of Albion Woodbury Small’s ‘School of Social Science’, at the newly-founded University of Chicago. The School’s thought developed from Small’s close association with William James, John Dewey, George Herbert Mead and Charles Cooley; all of whom emphasised the individual and the importance of that individual’s empirical perception or experience, and subscribed to a Darwinian view of evolution and natural history. The School’s early links with anthropology (exemplified chiefly by the work of William Isaac Thomas) and economics, would contribute to the development of an easily recognisable methodology. This was field-based statistical research, for the most part carried out within the urban locality of Chicago, which viewed criminality – especially juvenile delinquency – as the product of purely sociological factors. The University of Chicago Press’s Sociological Series (characterised by its distinctively modern and attractive book design, which influenced the nearby Free Press of Glencoe, Illinois) was responsible for distributing much of the School’s core work, beginning with Nels Anderson’s The Hobo in 1923. -

Crime Theory Tweets 140 Character Summaries of Popular Criminological Theories Justin W

Crime Theory Tweets 140 Character Summaries of Popular Criminological Theories Justin W. Patchin, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire (CRMJ 301) Theory Main Theorist(s) Summary Classical school of Beccaria Crime is inherently rewarding. People offend based on a free will choice. To prevent, criminology must punish so potential benefit not worth it. Positivist school of Lombroso Born criminals. Crime caused by something beyond person’s control (usually biological criminology or psychological). Social disorganization Park & Burgess; Shaw & High mobility areas result in inability of neighbors to organize in defense of common McKay; Sampson values. Physical disorder symbols of social breakdown. Broken Windows Wilson and Kelling Criminal behavior thrives in areas where residents are apathetic toward their environment and neighbors (absence of collective efficacy). General theory of crime Gottfredson & Hirschi Crime & deviance a result of low self-control. One’s level of self-control stabile at age 8. Opportunity also important. Social bonding theory Hirschi Our bond (attachment, commitment, involvement, belief) to parents & others restrains our innate desire to engage in deviance. Strain theory Merton Pursuit of American Dream (wealth accumulation) is main cause of crime. Some will do (classic/anomie) whatever is necessary to acquire $$$. Strain theory Cloward & Ohlin Illegitimate means to achieve wealth are also inaccessible to some. Perception is that joining a gang increases opportunities. Strain theory Cohen Some youth are unable to achieve middle-class standards so they supplant legit pursuits with desire to achieve status/respect among peers. General strain theory Agnew Strain plus negative affect equals crime. 3 sources: inability to achieve; something valued removed; something painful introduced. -

Social Disorganization Theory: the Role of Diversity in New Jersey's Hate Crimes Dana Maria Ciobanu Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2016 Social Disorganization Theory: The Role of Diversity in New Jersey's Hate Crimes Dana Maria Ciobanu Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Criminology Commons, Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, Public Administration Commons, and the Public Policy Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Dana Ciobanu has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Patricia Ripoll, Committee Chairperson, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Gema Hernandez, Committee Member, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Matthew Jones, University Reviewer, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2016 Abstract Social Disorganization Theory: The Role of Diversity in New Jersey’s Hate Crimes by Dana Maria Ciobanu MPA, Seton Hall University, 2005 MADIR, Seton Hall University, 2005 BA, Seton Hall University, 2000 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Policy and Administration Walden University August 2016 Abstract The reported number of hate crimes in New Jersey continues to remain high despite the enforcement of laws against perpetrators.