Theoretical Pluralism and Sociological Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociology 265B

SOCIOLOGY 316 An Introduction to Sociological Theory Fall 2002 Instructor: Gary Hamilton RETHINKING DEMOCRACY: THE ORIGINS OF AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY Purpose: There are a number of ways to introduce sociological theory to undergraduates. The way I have chosen to teach this course is to place sociological theory in the historical and social context of its creation. In so doing, I want to stress the complex relationship between the theorist and his or her intellectual environment, a relationship that has direct and indirect bearings on the theories themselves. The historical and social setting that I have selected for this course is the United States in the late 19th and early 20th century, roughly from 1880-1920. This is the time when, and the place that, sociology became an established social science discipline. I should note that many textbooks in sociological theory depict the “forefathers” of sociology as being the European triumvirate: Marx, Durkheim, and Weber. Yet if we examine the history of sociology carefully, we will see that this conventional depiction is not only poor history, but also poor sociology. Even though Americans took the idea and the term of “sociology” from Europeans, sociology, as a discipline of academic study, began in the United States. It is this formative period of sociology that we will examine in this course. I believe you will find that there is much to learn about our lives and our social thinking today from this examination of an earlier time. Required Readings: There are two required readings: 1. A reader. 2. Louis Menand, The Metaphysical Club, A Story of Ideas in America. -

Advanced Sociological Theory SOCI 6305, Section 1

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF WEST GEORGIA Spring 2017 Advanced Sociological Theory SOCI 6305, Section 1 Tuesday, 5:30-8:00 PM, Pafford 306 Dr. Emily McKendry-Smith Office: Pafford 319 Office hours: Mon. 1-2, 3:30-4:30, Tues. 1-5, and Weds. 11-2, 3:30-4:30, or by appointment Email: [email protected] Do NOT email me using CourseDen! “Social theory is a basic survival skill. This may surprise those who believe it to be a special activity of experts of a certain kind. True, there are professional social theorists, usually academics. But this fact does not exclude my belief that social theory is something done necessarily, and often well, by people with no particular professional credential. When it is done well, by whomever, it can be a source of uncommon pleasure.” – Charles Lemert, 1993 Course Information and Goals: This course provides a foundation in the key components of classical and contemporary social theory, as used by academic sociologists. This course is a seminar, not a lecture series. Unlike undergraduate courses, the purpose of this course is not to memorize a set of “facts,” but to develop your critical thinking skills by using them to evaluate theory. Instead, this course will consist of discussions centered on key questions from the readings. This course format requires that you be active participants. If discussion does not emerge spontaneously, I will prompt it by asking questions and pushing for your point of view. (That said, some of these theories can be difficult to understand; I will help you with this and we will work together in class to uncover the readings’ main points). -

SOC 103: Sociological Theory Tufts University Department of Sociology

SOC 103: Sociological Theory Tufts University Department of Sociology Image courtesy of Owl Turd Comix: http://shencomix.com *Syllabus updated 1-20-2018 When: Mondays & Wednesdays, 3:00-4:15 Where: 312 Anderson Hall Instructor: Assistant Professor Freeden Blume Oeur Grader: Laura Adler, Sociology Ph.D. student, Harvard University Email: [email protected] Phone: 617.627.0554 Office: 118 Eaton Hall Website: http://sites.tufts.edu/freedenblumeoeur/ Office Hours: Drop-in Tuesdays 2-3:30 & Thursdays 10-11:30; and by appointment WELCOME The Greek root of theory is theorein, or “to look at.” Sociological theories are therefore visions, or ways of seeing and interpreting the social world. Some lenses have a wide aperture and seek to explain macro level social developments and historical change. The “searchlight” (to borrow Alfred Whitehead’s term) for other theories could be narrower, but their beams may offer greater clarity for things within their view. All theories have blind spots. This course introduces you to an array of visions on issues of enduring importance for sociology, such as alienation and emancipation, solidarity and integration, domination and violence, epistemology, secularization and rationalization, and social transformation and social reproduction. This course will highlight important 1 theories that have not been part of the sociological “canon,” while also introducing you to more classical theories. Mixed in are a few poignant case studies. We’ll also discuss the (captivating, overlooked, even misguided) origins of modern sociology. I hope you enjoy engaging with sociological theory as much as I do. I think it’s the sweetest thing. We’ll discuss why at the first class. -

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations NCSS Strands: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions Time, Continuity, and Change Grade level: 9-12 Class periods needed: 1.5- 50 minute periods Purpose, Background, and Context Sociologists seek to understand how and why deviance occurs within a society. They do this by developing theories that explain factors impacting deviance on a wide scale such as social frustrations, socialization, social learning, and the impact of labeling. Four main theories have developed in the last 50 years. Anomie: Deviance is caused by anomie, or the feeling that society’s goals or the means to achieve them are closed to the person Control: Deviance exists because of improper socialization, which results in a lack of self-control for the person Differential association: People learn deviance from associating with others who act in deviant ways Labeling: Deviant behavior depends on who is defining it, and the people in our society who define deviance are usually those in positions of power Students will participate in a “jigsaw” where they will become knowledgeable in one theory and then share their knowledge with the rest of the class. After all theories have been presented, the class will use the theories to explain an historic example of socially deviant behavior: Zoot Suit Riots. Objectives & Student Outcomes Students will: Be able to define the concepts of social norms and deviance 1 Brainstorm behaviors that fit along a continuum from informal to formal deviance Learn four sociological theories of deviance by reading, listening, constructing hypotheticals, and questioning classmates Apply theories of deviance to Zoot Suit Riots that occurred in the 1943 Examine the role of social norms for individuals, groups, and institutions and how they are reinforced to maintain a order within a society; examine disorder/deviance within a society (NCSS Standards, p. -

Sociological Functionalist Theory That Shapes the Filipino Social Consciousness in the Philippines

Title: The Missing Sociological Imagination: Sociological Functionalist Theory That Shapes the Filipino Social Consciousness in the Philippines Author: Prof. Kathy Westman, Waubonsee Community College, Sugar Grove, IL Summary: This lesson explores the links on the development of sociology in the Philippines and the sociological consciousness in the country. The assumption is that limited growth of sociological theory is due to the parallel limited growth of social modernity in the Philippines. Therefore, the study of sociology in the Philippines takes on a functionalist orientation limiting development of sociological consciousness on social inequalities. Sociology has not fully emerged from a modernity tool in transforming Philippine society to a conceptual tool that unites Filipino social consciousness on equality. Objectives: 1. Study history of sociology in the Philippines. 2. Assess the application of sociology in context to the Philippine social consciousness. 3. Explore ways in which function over conflict contributes to maintenance of Filipino social order. 4. Apply and analyze the links between the current state of Philippine sociology and the threats on thought and freedoms. 5. Create how sociology in the Philippines can benefit collective social consciousness and of change toward social movements of equality. Content: Social settings shape human consciousness and realities. Sociology developed in western society in which the constructions of thought were unable to explain the late nineteenth century systemic and human conditions. Sociology evolved out of the need for production of thought as a natural product of the social consciousness. Sociology came to the Philippines in a non-organic way. Instead, sociology and the social sciences were brought to the country with the post Spanish American War colonization by the United States. -

Three Faces of Cruelty: Towards a Comparative Sociology of Violence Author(S): Randall Collins Source: Theory and Society, Vol

Three Faces of Cruelty: Towards a Comparative Sociology of Violence Author(s): Randall Collins Source: Theory and Society, Vol. 1, No. 4 (Winter, 1974), pp. 415-440 Published by: Springer Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/656911 Accessed: 12/06/2009 07:41 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=springer. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Theory and Society. http://www.jstor.org 415 THREE FACES OF CRUELTY: TOWARDS A COMPARATIVE SOCIOLOGYOF VIOLENCE RANDALL COLLINS To the comparativesociologist, history shows itself on two levels. -

Centennial Bibliography on the History of American Sociology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2005 Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology Michael R. Hill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Hill, Michael R., "Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology" (2005). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 348. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/348 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hill, Michael R., (Compiler). 2005. Centennial Bibliography of the History of American Sociology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. CENTENNIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN SOCIOLOGY Compiled by MICHAEL R. HILL Editor, Sociological Origins In consultation with the Centennial Bibliography Committee of the American Sociological Association Section on the History of Sociology: Brian P. Conway, Michael R. Hill (co-chair), Susan Hoecker-Drysdale (ex-officio), Jack Nusan Porter (co-chair), Pamela A. Roby, Kathleen Slobin, and Roberta Spalter-Roth. © 2005 American Sociological Association Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS Note: Each part is separately paginated, with the number of pages in each part as indicated below in square brackets. The total page count for the entire file is 224 pages. To navigate within the document, please use navigation arrows and the Bookmark feature provided by Adobe Acrobat Reader.® Users may search this document by utilizing the “Find” command (typically located under the “Edit” tab on the Adobe Acrobat toolbar). -

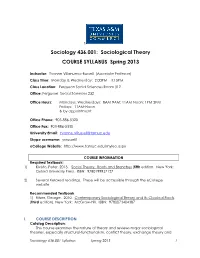

Sociological Theory COURSE SYLLABUS Spring 2013

t Sociology 436.001: Sociological Theory COURSE SYLLABUS Spring 2013 Instructor: Yvonne Villanueva-Russell (Associate Professor) Class Time: Monday & Wednesday: 2:00PM – 3:15PM Class Location: Ferguson Social Sciences Room 312 Office: Ferguson Social Sciences 232 Office Hours: Mondays, Wednesdays: 8AM-9AM; 11AM-Noon; 1PM-2PM Fridays: 11AM-Noon & by appointment Office Phone: 903-886-5320 Office Fax: 903-886-5330 University Email: [email protected] Skype username: yvrussell1 eCollege Website: http://www.tamuc.edu/myleo.aspx COURSE INFORMATION Required Textbook: 1) Kivisto, Peter. 2013. Social Theory: Roots and Branches (fifth edition. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780199937127 2) Several Xeroxed readings. These will be accessible through the eCollege website Recommended Textbook 1) Ritzer, George. 2010. Contemporary Sociological Theory and Its Classical Roots. (third edition). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN: 9780073404387 I. COURSE DESCRIPTION Catalog Description: This course examines the nature of theory and reviews major sociological theories, especially structural-functionalism, conflict theory, exchange theory and Sociology 436.001 Syllabus Spring 2013 1 interactionism. Special attention is given to leading figures representing the above schools of thought. Prerequisite: Sociology 111 or its equivalent. Student Learning Outcomes 1) Students will demonstrate comprehension of the major sociological theorist’s ideas and concepts as measured through examinations and online discussion boards 2) Students will demonstrate the ability to apply sociological concepts and theories through written essays Course Format: This course will revolve around numerous readings and active discussion in class of these selections, as well as lecture to supplement and provide background information on each theorist or theoretical paradigm. We will spend the bulk of time wading through and struggling to understand the writings through primary readings composed by the actual theorists, themselves. -

The Great Debate

01-Sernau.qxd 4/11/2005 11:32 AM Page 3 1 The Great Debate An imbalance between rich and poor is the oldest and most fatal ailment of all republics. —Plutarch, Greek philosopher (c. 46–120 A.D.) Inequality, rather than want, is the cause of trouble. —ancient Chinese saying The prince should try to prevent too great an inequality of wealth. —Erasmus, Dutch scholar (1465–1536) Consider the following questions for a moment: Is inequality a good thing? And good for whom? This is a philosophical rather than an empirical question—not is inequality inevitable, but is it good? Some measure of inequality is almost universal; inequalities occur everywhere. Is this because inequality is inevitable, or is it just a universal hindrance (perhaps like prejudice, intolerance, ethnocentrism, and violence)? Is inequality necessary to motivate people, or can they be motivated by other factors, such as a love of the common good or the intrinsic interest of a par- ticular vocation? Note that not everyone, even among today’s supposedly highly materialistic college students, chooses the most lucrative profession. Volunteerism seems to be gaining in importance rather than disappearing among college students and recent graduates. Except for maybe on a few truly awful days, I would not be eager to stop teaching sociology and start emptying wastebaskets at my university, even if the compensation for the two jobs were equal. What is it that motivates human beings? 3 01-Sernau.qxd 4/11/2005 11:32 AM Page 4 4 PART I ❖ ROOTS OF INEQUALITY Inequality by what criteria? If we seek equality, what does that mean? Do we seek equality of opportunities or equality of outcomes? Is the issue one the process? Is inequality acceptable as long as fair competition and equal access exist? In many ways, this might be the American ideal. -

Mode of Production and Mode of Exploitation: the Mechanical and the Dialectical'

DjalectiCalAflthropologY 1(1975) 7 — 2 3 © Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam — Printed in The Netherlands MODE OF PRODUCTION AND MODE OF EXPLOITATION: THE MECHANICAL AND THE DIALECTICAL' Eugene E. Ruyle In the social production of their life, men enter into definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will, relations of production which correspond to a definite stage of development of their material produc- tive forces. The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which rises a legal and political superstruc- ture and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the social, political and intellectual life process in general. It is not the consciousness of men that deter- mines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness.2 The specific economic form, in which unpaid surplus labor is pumped out of the direct producers, determines the relation of rulers and ruled, as it grows immediately out of production itself and in turn reacts upon it as a determining agent. .. It is always the direct relation of the owners of the means of production to the direct producers which reveals the innermost secret, the hidden foundation of the entire social structure.3 In the first of these two passages, Marx in crypto-Marxist bourgeois social science, and appears to be arguing for the sort of techno- then by exploring the possibilities of supple- economic determinism which has become menting the "mode of production" approach increasingly fashionable in bourgeois social with a "mode of exploitation" analysis. -

SOCIOLOGY of RELIGION Robert Wuthnow These Readings Will Expose You to the Central Ideas That Have Shaped the Sociology of Relig

SOCIOLOGY OF RELIGION Robert Wuthnow These readings will expose you to the central ideas that have shaped the sociology of religion. The list emphasizes major theoretical and theoretically informed substantive contributions, including some from anthropology and history as well as sociology. The basic readings are starred (*) and should be read carefully. Following each set of basic readings is a short selection of supplementary readings. These are meant to provide more recent and/or advanced understanding of how the core perspective has been extended or applied, or in some cases to suggest alternative approaches and applications. You should pick one of these supplementary readings from each section. In most instances, you may pick either a more theoretically oriented reading or a more empirically oriented study, depending on your interests. Mastering the basic readings and one supplementary reading from each section will give you about 90 percent of what you need to know for the General Examination in sociology of religion. The remaining 10 percent should be composed of recent literature in a sub- area related to your dissertation interests. The reading course will meet each week for one to one and a half hours. Please write and circulate a two-page memo in advance summarizing your thoughts about what you have read and raising questions for discussion. If the week's readings are new to you, focus on the basic readings; if you are already familiar with the basic readings, review them and come prepared to make a short presentation about one of the supplementary readings. For an extensive bibliography and sampling of topics covered in an undergraduate course in sociology of religion, see Meredith McGuire, Religion: The Social Context, 5th ed. -

Origins of the Myth of Social Darwinism: the Ambiguous Legacy of Richard Hofstadter’S Social Darwinism in American Thought

Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 71 (2009) 37–51 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jebo Origins of the myth of social Darwinism: The ambiguous legacy of Richard Hofstadter’s Social Darwinism in American Thought Thomas C. Leonard Department of Economics, Princeton University, Fisher Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544, United States article info abstract Article history: The term “social Darwinism” owes its currency and many of its connotations to Richard Received 19 February 2007 Hofstadter’s influential Social Darwinism in American Thought, 1860–1915 (SDAT). The post- Accepted 8 November 2007 SDAT meanings of “social Darwinism” are the product of an unresolved Whiggish tension in Available online 6 March 2009 SDAT: Hofstadter championed economic reform over free markets, but he also condemned biology in social science, this while many progressive social scientists surveyed in SDAT JEL classification: offered biological justifications for economic reform. As a consequence, there are, in effect, B15 B31 two Hofstadters in SDAT. The first (call him Hofstadter1) disparaged as “social Darwinism” B12 biological justification of laissez-faire, for this was, in his view, doubly wrong. The sec- ond Hofstadter (call him Hofstadter2) documented, however incompletely, the underside Keywords: of progressive reform: racism, eugenics and imperialism, and even devised a term for it, Social Darwinism “Darwinian collectivism.” This essay documents and explains Hofstadter’s ambivalence in Evolution SDAT, especially where, as with Progressive Era eugenics, the “two Hofstadters” were at odds Progressive Era economics Malthus with each other. It explores the historiographic and semantic consequences of Hofstadter’s ambivalence, including its connection with the Left’s longstanding mistrust of Darwinism as apology for Malthusian political economy.