Foundations of Cognitive Psychology Core Readings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developmental Dynamics: Toward a Biologically Plausible Evolutionary Psychology

Psychological Bulletin Copyright 2003 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 2003, Vol. 129, No. 6, 819–835 0033-2909/03/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.6.819 Developmental Dynamics: Toward a Biologically Plausible Evolutionary Psychology Robert Lickliter Hunter Honeycutt Florida International University Indiana University Bloomington There has been a conceptual revolution in the biological sciences over the past several decades. Evidence from genetics, embryology, and developmental biology has converged to offer a more epigenetic, contingent, and dynamic view of how organisms develop. Despite these advances, arguments for the heuristic value of a gene-centered, predeterministic approach to the study of human behavior and development have become increasingly evident in the psychological sciences during this time. In this article, the authors review recent advances in genetics, embryology, and developmental biology that have transformed contemporary developmental and evolutionary theory and explore how these advances challenge gene-centered explanations of human behavior that ignore the complex, highly coordinated system of regulatory dynamics involved in development and evolution. The prestige of success enjoyed by the gene theory might become a evolutionary psychology assert that applying insights from evolu- hindrance to the understanding of development by directing our tionary theory to explanations of human behavior will stimulate attention solely to the genome....Already we have theories that refer more fruitful research programs and provide a powerful frame- the processes of development to genic action and regard the whole work for discovering evolved psychological mechanisms thought performance as no more than the realization of the potencies of the genes. Such theories are altogether too one-sided. -

The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the 20Th Century

Review of General Psychology Copyright 2002 by the Educational Publishing Foundation 2002, Vol. 6, No. 2, 139–152 1089-2680/02/$5.00 DOI: 10.1037//1089-2680.6.2.139 The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the 20th Century Steven J. Haggbloom Renee Warnick, Jason E. Warnick, Western Kentucky University Vinessa K. Jones, Gary L. Yarbrough, Tenea M. Russell, Chris M. Borecky, Reagan McGahhey, John L. Powell III, Jamie Beavers, and Emmanuelle Monte Arkansas State University A rank-ordered list was constructed that reports the first 99 of the 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century. Eminence was measured by scores on 3 quantitative variables and 3 qualitative variables. The quantitative variables were journal citation frequency, introductory psychology textbook citation frequency, and survey response frequency. The qualitative variables were National Academy of Sciences membership, election as American Psychological Association (APA) president or receipt of the APA Distinguished Scientific Contributions Award, and surname used as an eponym. The qualitative variables were quantified and combined with the other 3 quantitative variables to produce a composite score that was then used to construct a rank-ordered list of the most eminent psychologists of the 20th century. The discipline of psychology underwent a eve of the 21st century, the APA Monitor (“A remarkable transformation during the 20th cen- Century of Psychology,” 1999) published brief tury, a transformation that included a shift away biographical sketches of some of the more em- from the European-influenced philosophical inent contributors to that transformation. Mile- psychology of the late 19th century to the stones such as a new year, a new decade, or, in empirical, research-based, American-dominated this case, a new century seem inevitably to psychology of today (Simonton, 1992). -

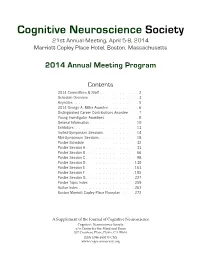

CNS 2014 Program

Cognitive Neuroscience Society 21st Annual Meeting, April 5-8, 2014 Marriott Copley Place Hotel, Boston, Massachusetts 2014 Annual Meeting Program Contents 2014 Committees & Staff . 2 Schedule Overview . 3 . Keynotes . 5 2014 George A . Miller Awardee . 6. Distinguished Career Contributions Awardee . 7 . Young Investigator Awardees . 8 . General Information . 10 Exhibitors . 13 . Invited-Symposium Sessions . 14 Mini-Symposium Sessions . 18 Poster Schedule . 32. Poster Session A . 33 Poster Session B . 66 Poster Session C . 98 Poster Session D . 130 Poster Session E . 163 Poster Session F . 195 . Poster Session G . 227 Poster Topic Index . 259. Author Index . 261 . Boston Marriott Copley Place Floorplan . 272. A Supplement of the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience Cognitive Neuroscience Society c/o Center for the Mind and Brain 267 Cousteau Place, Davis, CA 95616 ISSN 1096-8857 © CNS www.cogneurosociety.org 2014 Committees & Staff Governing Board Mini-Symposium Committee Roberto Cabeza, Ph.D., Duke University David Badre, Ph.D., Brown University (Chair) Marta Kutas, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Adam Aron, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Helen Neville, Ph.D., University of Oregon Lila Davachi, Ph.D., New York University Daniel Schacter, Ph.D., Harvard University Elizabeth Kensinger, Ph.D., Boston College Michael S. Gazzaniga, Ph.D., University of California, Gina Kuperberg, Ph.D., Harvard University Santa Barbara (ex officio) Thad Polk, Ph.D., University of Michigan George R. Mangun, Ph.D., University of California, -

Mental Imagery: in Search of a Theory

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2002) 25, 157–238 Printed in the United States of America Mental imagery: In search of a theory Zenon W. Pylyshyn Rutgers Center for Cognitive Science, Rutgers University, Busch Campus, Piscataway, NJ 08854-8020. [email protected] http://ruccs.rutgers.edu/faculty/pylyshyn.html Abstract: It is generally accepted that there is something special about reasoning by using mental images. The question of how it is spe- cial, however, has never been satisfactorily spelled out, despite more than thirty years of research in the post-behaviorist tradition. This article considers some of the general motivation for the assumption that entertaining mental images involves inspecting a picture-like object. It sets out a distinction between phenomena attributable to the nature of mind to what is called the cognitive architecture, and ones that are attributable to tacit knowledge used to simulate what would happen in a visual situation. With this distinction in mind, the paper then considers in detail the widely held assumption that in some important sense images are spatially displayed or are depictive, and that examining images uses the same mechanisms that are deployed in visual perception. I argue that the assumption of the spatial or depictive nature of images is only explanatory if taken literally, as a claim about how images are physically instantiated in the brain, and that the literal view fails for a number of empirical reasons – for example, because of the cognitive penetrability of the phenomena cited in its favor. Similarly, while it is arguably the case that imagery and vision involve some of the same mechanisms, this tells us very little about the nature of mental imagery and does not support claims about the pictorial nature of mental images. -

How a Cognitive Psychologist Came to Seek Universal Laws

Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 2004, 11 (1), 1-23 PSYCHONOMIC SOCIETY KEYNOTE ADDRESS How a cognitive psychologist came to seek universal laws ROGERN. SHEPARD Stanford University, Stanford, California and Arizona Senior Academy, Tucson, Arizona Myearlyfascination with geometry and physics and, later, withperception and imagination inspired a hope that fundamental phenomena ofpsychology, like those ofphysics, might approximate univer sal laws. Ensuing research led me to the following candidates, formulated in terms of distances along shortestpaths in abstractrepresentational spaces: Generalization probability decreases exponentially and discrimination time reciprocally with distance. Time to determine the identity of shapes and, pro visionally, relation between musical tones or keys increases linearly with distance. Invariance of the laws is achieved by constructing the representational spaces from psychological rather than physical data (using multidimensional scaling) and from considerations of geometry, group theory, and sym metry. Universality of the laws is suggested by their behavioral approximation in cognitively advanced species and by theoretical considerations of optimality. Just possibly, not only physics but also psy chology can aspire to laws that ultimately reflect mathematical constraints, such as those ofgroup the ory and symmetry, and, so, are both universal and nonarbitrary. The object ofall science, whether natural science or psy three principal respects. The first is my predilection for chology, is to coordinate our experiences and to bring them applying mathematical ideas that are often ofa more geo into a logical system. metrical or spatial character than are the probabilistic or (Einstein, 1923a, p. 2) statistical concepts that have generally been deemed [But] the initial hypotheses become steadily more abstract most appropriate for the behavioral and social sciences. -

Experimente Clasice in Psihologie

PSIHOLOGIE - PSIHOTERAPIE Colecţie coordonată de Simona Reghintovschi DOUGLAS MOOK Experimente clasice în psihologie Traducere din engleză de Clara Ruse Prefaţă la ediţia în limba română de Mihai Aniţei A TRei Editori SILVIU DRAGOMIR VASILE DEM. ZAMFIRESCU Director editorial MAGDALENA MÂRCULESCU Coperta FABER STUDIO (S. OLTEANU, A. RĂDULESCU, D. DUMBRĂVICIAN) Redactor RALUCA HURDUC Director producţie CRISTIAN CLAUDIU COBAN Dtp MARIAN CONSTANTIN Corectori ELENA BIŢU EUGENIA URSU Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii Naţionale a României MOOK, DOUGLAS Experimente clasice în psihologie / Douglas Mook; trad.: Clara Ruse. - Bucureşti: Editura Trei, 2009 ISBN 978-973-707-286-3 I. Ruse, Clara (trad.) 159.9 Această carte a fost tradusă după Classic Experiments in Psychology de Douglas Mook, Editura Greenwood Press, imprintal Grupului Editorial Greenwood, Westport, CT, U.S.A. (http://www.greenwood.com/greenwood_press.aspx) Copyright © 2004 by Douglas Mook Copyright © Editura Trei, 2009 pentru prezenta ediţie C.P. 27-0490, Bucureşti Tel./Fax: +4 021300 60 90 e-mail: [email protected] www.edituratrei.ro ISBN 978-973-707-286-3 în memoria lui Eliot Stellar, care ar fi -putut o scrie mai bine. Cuprins Prefaţă la ediţia română (de Prof.univ.dr. Mihai Aniţei)................................. 11 Prefaţă .............................................................................................................................. 15 Mulţumiri.........................................................................................................................17 -

Gordon Bower Papers SC1223

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8ff3z2n Online items available Guide to the Gordon Bower papers SC1223 Jenny Johnson Department of Special Collections and University Archives Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Gordon Bower SC1223 1 papers SC1223 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Gordon Bower papers Creator: Bower, Gordon H. Identifier/Call Number: SC1223 Physical Description: 24.75 Linear Feet17 boxes and 6.32 GB of digital files Date (inclusive): 1950-2016 Language of Material: English Access to Collection Recommendations and student materials are closed for 75 years from date of creation. Otherwise tThe materials are open for research use. Audio-visual materials are not available in original format, and must be reformatted to a digital use copy. Publication Rights All requests to reproduce, publish, quote from, or otherwise use collection materials must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94305-6064. Consent is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission from the copyright owner. Such permission must be obtained from the copyright owner, heir(s) or assigns. See: http://library.stanford.edu/spc/using-collections/permission-publish. Restrictions also apply to digital representations of the original materials. Use of digital files is restricted to research and educational purposes. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Gordon Bower papers (SC1223). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. -

Fact, Fiction, and Fitness

entropy Article Fact, Fiction, and Fitness Chetan Prakash 1, Chris Fields 2 , Donald D. Hoffman 3, Robert Prentner 3 and Manish Singh 4,* 1 Department of Mathematics, California State University, San Bernardino, CA 92407, USA; [email protected] 2 Independent Researcher, 23 rue des Lavandières, 11160 Caunes Minervois, France; fi[email protected] 3 Department of Cognitive Sciences, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697, USA; [email protected] (D.D.H.); [email protected] (R.P.) 4 Department of Psychology and Center for Cognitive Science, Rutgers University, New Brunswick/Piscataway Campus, NJ 08854, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 March 2020; Accepted: 22 April 2020; Published: 30 April 2020 Abstract: A theory of consciousness, whatever else it may do, must address the structure of experience. Our perceptual experiences are richly structured. Simply seeing a red apple, swaying between green leaves on a stout tree, involves symmetries, geometries, orders, topologies, and algebras of events. Are these structures also present in the world, fully independent of their observation? Perceptual theorists of many persuasions—from computational to radical embodied—say yes: perception veridically presents to observers structures that exist in an observer-independent world; and it does so because natural selection shapes perceptual systems to be increasingly veridical. Here we study four structures: total orders, permutation groups, cyclic groups, and measurable spaces. We ask whether the payoff functions that drive evolution by natural selection are homomorphisms of these structures. We prove, in each case, that generically the answer is no: as the number of world states and payoff values go to infinity, the probability that a payoff function is a homomorphism goes to zero. -

Representing Geometry: Perception, Concepts, and Knowledge

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Representing Geometry: Perception, Concepts, and Knowledge DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Philosophy by J. Ethan Galebach Dissertation Committee: Professor Jeremy Heis, Chair Professor Penelope Maddy Professor Sean Walsh 2018 c 2018 J. Ethan Galebach TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgments iv Curriculum Vitae vii Abstract of the Dissertation viii Introduction 1 1 Does Visual Perception Have a Geometry? 5 1.1 Introduction . 6 1.2 VMS Proponents and Arguments . 8 1.2.1 What is Visual Perception? . 8 1.2.2 Five Arguments for a VMS . 11 1.2.3 Behavioral evidence against a VMS . 26 1.3 Spatial Representation according to Vision Science . 30 1.3.1 Marr's visual perception: demarcation and primary function . 30 1.3.2 Current Views on Shape and Scene Perception . 36 1.4 Conclusion and Open Questions . 43 1.5 Bibliography . 44 2 Are Euclidean Beliefs Grounded in Core Cognitive Systems? 57 2.1 Introduction . 57 2.2 The Core Cognitive Theory of Numerical Concept Acquisition . 58 2.2.1 Two Core Systems of Number . 59 2.2.2 Bootstrapping to Numerical Concepts and Arithmetical Beliefs . 62 2.3 The Core Cognitive Theory of Geometric Concept Acquisition . 65 2.3.1 Two Core Systems of Geometry . 67 2.3.2 Bootstrapping to Geometric Concepts and Beliefs . 70 2.4 Problems for the Core Cognitive Theory of Geometry . 71 2.4.1 Critique of the Two Core Systems of Geometry . 71 2.4.2 Critique of the Proposed Geometric Concepts and Beliefs . -

Psychologues Américains

Psychologues américains A G (suite) M (suite) • Robert Abelson • Gustave M. Gilbert • Christina Maslach • Gordon Willard • Carol Gilligan • Abraham Maslow Allport • Stephen Gilligan • David McClelland • Richard Alpert • Daniel Goleman • Phil McGraw • Dan Ariely • Thomas Gordon • Albert Mehrabian • Solomon Asch • Temple Grandin • Stanley Milgram • Blake Ashforth • Clare Graves • Geoffrey Miller • David Ausubel • Joy Paul Guilford (psychologue) • Moubarak Awad • George Armitage H Miller B • Theodore Millon • G. Stanley Hall • James Baldwin • Daria Halprin N (psychologue) • Harry Harlow • Theodore Barber • Alan Hartman • Ulric Neisser • Gregory Bateson • Torey Hayden • Richard Noll • Diana Baumrind • Frederick Herzberg • Alex Bavelas • Ernest Hilgard O • Don Beck • James Hillman • Benjamin Bloom • Allan Hobson • James Olds • Edwin Garrigues • John L. Holland Boring • John Henry Holland P • Loretta Bradley • Evelyn Hooker • Nathaniel Branden • Carl Hovland • Baron Perlman • Urie Bronfenbrenner • Clark Leonard Hull • Walter Pitts • Joyce Brothers • Jerome Bruner J R • David Buss • Howard Buten • William James • Joseph Banks Rhine • Kay Redfield Jamison • Kenneth Ring C • Irving Janis • Judith Rodin • Arthur Janov • Carl Rogers • John Bissell Carroll • Joseph Jastrow • Milton Rokeach • James McKeen Cattell • Julian Jaynes • Eleanor Rosch • Raymond Cattell • Arthur Jensen • Marshall Rosenberg • Cary Cherniss • Frank Rosenblatt • Robert Cialdini K • Robert Rosenthal • Mary Cover Jones • Julian Rotter • Lee Cronbach • Daniel Kahneman • Paul Rozin -

The Role of Animal Psychology in the Study of Human Behavior

eScholarship International Journal of Comparative Psychology Title Adaption Versus Phylogeny: The Role of Animal Psychology in The Study of Human Behavior Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/19q5b46g Journal International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 2(3) ISSN 0889-3675 Authors Tooby, John Cosmides, Leda Publication Date 1989 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The International Journal of Comparative Psychology, Vol. 2, No. 3, Spring 1989 ADAPTATION VERSUS PHYLOGENY: THE ROLE OF ANIMAL PSYCHOLOGY IN THE STUDY OF HUMAN BEHAVIOR John Tooby and Leda Cosmides Stanford University ABSTRACT: Advocates of Darwinian approaches to the study of behavior are divided over what an evolutionary perspective is thought to entail. Some take "evolution-minded- ness" to mean "phylogeny-mindedness," whereas others take it to mean "adaptation- mindedness." Historically, comparative psychology began as the search for mental continuities between humans and other animals: a phylogenetic approach. Independently, ethologists and now behavioral ecologists have placed far more emphasis on the niche- differentiated mental abilities unique to the species being investigated: an adaptive approach. We argue that the output of complex, dynamical systems can be dramatically changed by only minor changes in internal structure. Because selection acts on the consequences of behavior, the behavioral output of the psyche will be easily shaped by adaptive demands over evolutionary time, even though the modification of the neuro- physiological substrate necessary to create such adaptive changes may be minor. Thus, adaptation-mindedness will be most illuminating in the study of cognition and behavior, whereas phylogeny-mindedness will be most illuminating in the study of their neuro- physiological substrates. -

General Psychologist a Publication of the Society for General Psychology ~ Division 1

TH E General Psychologist A Publication of the Society for General Psychology ~ Division 1 Inside this issue President’s Col- umn (2) Invitation to Social Hour (3- 4) Division 1 Pro- gram Schedule (6-7) Division 1 By- laws (8-11) Featured Article on The Female Psyche (14) Featured Com- mentary on The Male Psyche (18) Special points of At our midwinter meeting in Washington D.C. in February 2017, we focused on two major interest items: (1) revising our bylaws; and (2) strategizing activities found effective with current Division One members, and creating enterprises to add new members. The revised bylaws Spotlight on are in this letter, open for your comments. In addition, the Division One program for the Past President APA Convention in August 2017 has been included to highlight events for you to meet (21) with Division One members, and spark discussions on all the diverse specialties in psychol- Invitation to ogy, or inquire about renewing your membership, becoming a Fellow or an Officer. We PROJECT SYL- will also be having a full program of events in our Division Suite in Room 6-126 in the LABUS Inter- Marriott Marquis hotel near the Convention Center. Please stop by! national(24) Our Fall/Winter Issue will profile our Award Recipients, New Fellows, current officers and Member Activi- new officers beginning this year! We Welcome You! ties (25) Member Current Back Row: Mindy Erchull (Fellows Committee Chair), Emily Dow (2017 Suite Program Chair & News & Inquiry Early Career Representative), Lisa Osbeck (Member-at-Large), Mark Sciutto (Member-at-Large), Clare (29) Mehta (2017 Program Chair), John Hogan (Historian), Alicia Trotman (Newsletter Editor), Emily Keener (Membership Chair), Kasey Powers (2017 Suite Program Chair & Student Representative), Book Reviews Phyllis Wentworth (2018 Program Chair), Avis Jackson (Webmaster) (39) Front Row: Anita M.