Judicial Intervention in a Twenty-First Century Republic: Shuffling Deck Chairs on the Titanic?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern First Ladies: Their Documentary Legacy. INSTITUTION National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 412 562 CS 216 046 AUTHOR Smith, Nancy Kegan, Comp.; Ryan, Mary C., Comp. TITLE Modern First Ladies: Their Documentary Legacy. INSTITUTION National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-911333-73-8 PUB DATE 1989-00-00 NOTE 189p.; Foreword by Don W. Wilson (Archivist of the United States). Introduction and Afterword by Lewis L. Gould. Published for the National Archives Trust Fund Board. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Archives; *Authors; *Females; Modern History; Presidents of the United States; Primary Sources; Resource Materials; Social History; *United States History IDENTIFIERS *First Ladies (United States); *Personal Writing; Public Records; Social Power; Twentieth Century; Womens History ABSTRACT This collection of essays about the Presidential wives of the 20th century through Nancy Reagan. An exploration of the records of first ladies will elicit diverse insights about the historical impact of these women in their times. Interpretive theories that explain modern first ladies are still tentative and exploratory. The contention in the essays, however, is that whatever direction historical writing on presidential wives may follow, there is little question that the future role of first ladies is more likely to expand than to recede to the days of relatively silent and passive helpmates. Following a foreword and an introduction, essays in the collection and their authors are, as follows: "Meeting a New Century: The Papers of Four Twentieth-Century First Ladies" (Mary M. Wolf skill); "Not One to Stay at Home: The Papers of Lou Henry Hoover" (Dale C. -

Mcgeorge Bundy Oral History Interview I, 1/30/69, by Paige E

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION LBJ Library 2313 Red River Street Austin, Texas 78705 http://www.lbjlib.utexas.edu/johnson/archives.hom/biopage.asp MCGEORGE BUNDY ORAL HISTORY, INTERVIEW I PREFERRED CITATION For Internet Copy: Transcript, McGeorge Bundy Oral History Interview I, 1/30/69, by Paige E. Mulhollan, Internet Copy, LBJ Library. For Electronic Copy on Compact Disc from the LBJ Library: Transcript, McGeorge Bundy Oral History Interview I, 1/30/69, by Paige E. Mulhollan, Electronic Copy, LBJ Library. INTERVIEW I DATE: January 30, 1969 INTERVIEWEE: McGEORGE BUNDY INTERVIEWER: Paige E. Mulhollan PLACE: Mr. Bundy's office, New York City Tape 1 of 1 M: Let's begin by way of identification. You are McGeorge Bundy, currently president of the Ford Foundation. Your government service, insofar as President Johnson's administration was concerned, lasted from the time he became president, when you were national security adviser, until you resigned in December of 1965 and left in what, February of 1966? B: The end of February, 1966. M: The end of February. One of the most frequent comments on Mr. Johnson as a foreign policy leader is that when he came to the presidency, he knew almost nothing about foreign affairs. Is this an accurate statement or assessment? B: Well, it is and it isn't. This was of course often said, and the President was sensitive to the fact that it was said. We were in the habit of explaining to the press, and I think perfectly fairly, that the fact that the President had not had formal diplomatic experience to any great extent was no true measure of the degree of his exposure to major questions in foreign affairs. -

Articles SANCTUARIES AS EQUITABLE DELEGATION in an ERA of MASS IMMIGRATION ENFORCEMENT

Copyright 2018 by Jason A. Cade Printed in U.S.A. Vol. 113, No. 3 Articles SANCTUARIES AS EQUITABLE DELEGATION IN AN ERA OF MASS IMMIGRATION ENFORCEMENT Jason A. Cade ABSTRACT—Opponents of—and sometimes advocates for—sanctuary policies describe them as obstructions to the operation of federal immigration law. This premise is flawed. On the better view, the sanctuary movement comports with, rather than fights against, dominant new themes in federal immigration law. A key theme—emerging both in judicial doctrine and on- the-ground practice—focuses on maintaining legitimacy by fostering adherence to equitable norms in enforcement decision-making processes. Against this backdrop, the sanctuary efforts of cities, churches, and campuses are best seen as measures necessary to inject normative (and sometimes legal) accuracy into real-world immigration enforcement decision-making. Sanctuaries can erect front-line equitable screens, promote procedural fairness, and act as last-resort circuit breakers in the administration of federal deportation law. The dynamics are messy and contested, but these efforts in the long run help ensure the vindication of equity-based legitimacy norms in immigration enforcement. AUTHOR—Associate Professor of Law, University of Georgia School of Law. This paper benefited from presentations at the 2018 American Association of Law Schools Annual Meeting, the 2017 People & Cultures Across Borders Conference held at Princeton University’s Institute for International & Regional Studies, the 2017 Emerging Immigration Law Scholars Conference held at Texas A&M University School of Law, and the 2017 Clinical Law Writers Workshop held at NYU School of Law. Thanks especially to Jennifer Koh, Ming Hsu Chen, Kevin Lapp, Usha Rodrigues, David Rubenstein, Dan Coenen, Carrie Rosenbaum, Annie Lai, Kit Johnson, Laila Hlass, Richard Boswell, Philip Torrey, David Baluarte, and Caitlin Berry for insightful comments. -

Spokes, Pyramids, and Chiefs of Staff: Howard H. Baker, Jr. and the Reagan Presidency

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2008 Spokes, Pyramids, and Chiefs of Staff: Howard H. Baker, Jr. and the Reagan Presidency Michael Lee Haynes University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the American Politics Commons Recommended Citation Haynes, Michael Lee, "Spokes, Pyramids, and Chiefs of Staff: Howard H. Baker, Jr. and the Reagan Presidency. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2008. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/384 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Michael Lee Haynes entitled "Spokes, Pyramids, and Chiefs of Staff: Howard H. Baker, Jr. and the Reagan Presidency." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Political Science. Michael R. Fitzgerald, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: John M. Scheb II, William Lyons, E. Grady Bogue Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Michael Lee Haynes entitled “Spokes, Pyramids, and Chiefs of Staff: Howard H. -

Your Name Here

JACKIE KENNEDY’S PRESIDENTIAL PERSONA: (RE)ASSESSING HER RHETORICAL INFLUENCE by COURTNEY ALEXSIS CAUDLE (Under the Direction of Edward Panetta) ABSTRACT In rhetorical studies, much has been written on the role of first lady and the women whom enacted this position. Scholars in several fields (history, rhetoric, popular culture) have examined First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy: however, this thesis supplements existing research both in first lady scholarship generally and on Jackie’s specific performance as first lady. I contend that Jackie’s performance remains unique because she carved a celebrity space both inimitable in the 1960s yet available to subsequent first ladies. I examine mediated texts (both visual and written) from 1961-1963 to (re)examine her enactment of the role during (1) President Kennedy’s Inauguration, (2) her televised tour of the White House, and (3) President Kennedy’s funeral. Ultimately, I argue she was integral to historical and contemporary public memory of his presidential persona and legacy. INDEX WORDS: Jacqueline Kennedy, First Ladies, Rhetoric, Visual analysis, Mediated communication, Gender, Celebrity, Cultural Studies JACKIE KENNEDY’S PRESIDENTIAL PERSONA: (RE)ASSESSING HER RHETORICAL INFLUENCE by COURTNEY ALEXSIS CAUDLE B.A., University of Florida, 2007 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 © 2009 Courtney Alexsis Caudle All Rights Reserved JACKIE KENNEDY’S PRESIDENTIAL PERSONA: (RE)ASSESSING HER RHETORICAL INFLUENCE by COURTNEY ALEXSIS CAUDLE Major Professor: Edward Panetta Committee: Thomas Lessl Roger Stahl Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia August 2009 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. -

Materials from the Johnson Library Pertaining to the Assassination of John F

National Archives and Records Administration http://archives.gov National Archives Catalog https://catalog.archives.gov http://www.lbjlibrary.org MATERIALS FROM THE JOHNSON LIBRARY PERTAINING TO THE ASSASSINATION OF JOHN F. KENNEDY INTRODUCTION This list includes the principal files in the Johnson Library that contain material relating to the assassination of John F. Kennedy. It is not definitive, however, and researchers should consult with the Library's archivists about other potentially useful files. The guide includes those collections which have been opened for research in part or in whole, and those collections which are currently unprocessed or unavailable. WHITE HOUSE CENTRAL FILES (WHCF) This permanent White House office was the main filing unit during the Johnson presidency, though not the primary file for foreign policy documents. Material was filed under 60 major subject headings, several of which are pertinent to the Kennedy assassination. Box # FE 3-1/Kennedy, John F. Federal Government Deaths/Funerals, JFK 3-5 EX FG 1 The President of the United States, 11/22/64-1/10/64 9 FG 2/Kennedy, John F. Former Presidents/Kennedy, John F. 40-41, 43-45 FG 635 Commission to Report on the Assassination of President John F. 376 Kennedy (Warren Commission) JL 3/FG 1 Justice - Legal Matters/Presidential Assassinations 37 JL 3/FG 2/Kennedy, John F. Justice Legal Matters/Former Presidents/ Kennedy, John F. 37 PP 1/FG 2/Kennedy, John F. President, Personal/Former Presidents/ Kennedy, John F. 9-10 02/28/17 1 National Archives and Records Administration http://archives.gov National Archives Catalog https://catalog.archives.gov http://www.lbjlibrary.org (Cross references and letters from the general public regarding the assassination.) PR 4-1 Public Relations - Support after the Death of John F. -

On the Cold War

NAME CLASS DATE On the Cold War The struggle with the Soviets provoked a range of responses from American leaders in the 1960s. As you read the passages below, tzy to relate each speaker s view of the cold war with his proposed strategies for dealing with cold-war issues. FOR CIVILITY IN THE COLD WAR FOR AGGRESSION IN THE COLD WAR Secretary of State Dean Rusk, speech at the Senator Barry Goldwater (R-Arizona), address to University of California, Berkeley, March 20, 1961 the U.S. Senate, July 14, 1961 L The cold war was not invented in the West; it was [I]t is our purpose to win the cold war, not merely born in the assault upon freedom which arose out wage it in the hope of attaining a standoff. [lit of the ashes of World War II. We might have is really astounding that our government has hoped that the fires of that struggle might have never stated its purpose to be that of complete consumed ambitions to dominate others.. But victory over the tyrannical forces of international such has not been the case. The issues called the communism. I am sure that the American people cold war are real and cannot be merely wished cannot understand why we spend billions upon away. They must be faced and met. But how we billions of dollars to engage in a struggle of meet them makes a difference. They will not be worldwide proportions unless we have a clearly scolded away by invective [harsh words] nor defined purpose to achieve victory. -

JACQUELINE KENNEDY and the POLITICS of POPULARITY by COURTNEY CAUDLE TRAVERS DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Th

JACQUELINE KENNEDY AND THE POLITICS OF POPULARITY BY COURTNEY CAUDLE TRAVERS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor John Murphy, Chair Associate Professor Cara Finnegan Associate Professor Ned O’Gorman Associate Professor Jennifer Greenhill Associate Professor Pat Gill Abstract Although her role as first lady marked the real beginning of the American public’s fascination with her, Jacqueline Kennedy’s celebrity status endured throughout her life. Dozens of books have sought to chronicle that mystique, hail her style, and commend her contribution to the youthful persona of the Kennedy administration. She seems to be an object ripe for rhetorical study; yet, for many communication scholars, Kennedy’s cultural iconicity diminishes her legacy as First Lady, and she remains an exemplar of political passivity. Her influence on the American public’s cultural and political imagination, however, demonstrates a need for scholars to assess with greater depth her development from First Lady to American icon in the early 1960s. Thus, this dissertation focuses on three case studies that analyze Jacqueline Kennedy’s image across different media: fashion spreads in Vogue magazine and Harper’s Bazaar published immediately after the inauguration in 1961; her televised tour of the White House broadcast in February 1962; and Andy Warhol’s 1964 Jackie prints, which drew from her construction of the Camelot myth after JFK’s funeral. These case studies seek to show how “icon” becomes an inventional and conceptual resource for the role of a modern first lady and how Kennedy’s shift to public icon in her own right (after and outside of her position as first lady) was mediated in nuanced ways that both reflected early Cold War (suburban) culture and shaped the larger institutional discourses of which she was part. -

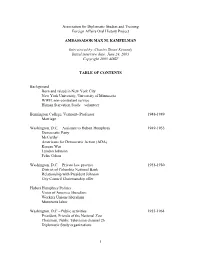

Max Kampelman at This Telephone Number; He‘Ll Be at the Bookstore

Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR MAX M. KAMPELMAN Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: June 24, 2003 Copyright 2005 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in Ne York City Ne York University, University of Minnesota WWII, non-combatant service Human Starvation Study + volunteer Bennington College, ,ermont- Professor 19.8-19.9 Marriage Washington, D.C. + Assistant to Hubert Humphrey 19.9-1922 Democratic Party McCarthy Americans for Democratic Action 3ADA4 5orean War 6yndon 7ohnson Feli8 Cohen Washington, D.C. + Private la practice 1922-1980 District of Columbia National Bank Relationship ith President 7ohnson City Council Chairmanship offer Hubert Humphrey Politics ,oice of America liberalism Workers Unions liberalism Minnesota labor Washington, D.C + Public activities 1922-196. President, Friends of the National Zoo Chairman, Public Television channel 26 Diplomatic Study organizations 1 Presidential Campaigns 196., 1968 and 1972 6yndon 7ohnson Hubert Humphrey ,ice-President@s Residence ,ietnam ,ice-Presidential candidates McAovern Richard Ni8on 7ack 5ennedy Committee on the Present Danger Presidential Elections 1976 Henry 3Scoop4 7ackson Hubert Humphrey Walter Mondale President 7immy Carter years 1977-1981 Afghanistan Madrid Conference + Chief of Delegation William Scranton Dante Fascell Helsinki Final Act Revie Arthur Aoldberg + Mid-East negotiator Aermans in USSR Soviet 7e s President Reagan Years + US Rep., Arms Reduction Negotiations -

The Assassination Question AIN.10".10

- 44' ' eteenee,'1.e,.-Wee.e.oe ,-. • . e R C l• • • • April, 1968 -- No. 78 t tt ladeeneetne neltXWMCNWCWOMile,GWeWineViNWO.., Fula ',;)olutions to the Assassination Question AIN.10".10.448`416:7-00004NNIC.A.-VAXVOIMCSIMMILVICI. C3M0006:7MOCIOMIMMiligN iVeliMMICMOMSKIPtilin% by Craig liarpel ' by Reginald Dunsany by Steve Klinger These p.1: reel,' lo have been vapor- New Orleans D.A. Jim Garrison's cour- "Mesa, Arizona—A laughing 18-year- ized."—/07: Garr-iron, District Attorney. ageout probe of the Kennedy assassination old boy who 'wanted to get known' Orleans Parish, .1,kuitiarta.;,.,:.-:::.1..., has confirmed the existence of a secret in- turned a beauty parlor into a slaughter. On Thursday,. Mk 61 T temational terrorist ring more deadly than house today when he shot four women opened the Idei#e YorIr .0011::.- to .the James Ochrana. GPU and Gestapo combined and a 3-year-old girl . (He said) —the Hornintern. Wechsleee nOldiret. litidnee.*' head.- that he had got the idea from recent mass killings in Chicago and Austin..." line' "IFK & Cnetro: Jost Intelligence agencies of the East and . -: y7" —News item f... rend: West have referred in hushed whispers to this !sinister camarilla of homosexual mili- In recent times, there has flowered in In his anal days on earth ... tarns ever since its founding in Lausanne, the United States a happy marriage of Kennedy was actively and WI , -tilr- Switzerland in 1931, but until Garrison two great AIngtican traditions, individual ly responding to overtures froin. Fidel . began his investigation, few hard facts con- initiative and.violenee. Not since the gang- Centro to" a detente with the United Smiled the lethal scope of its activities. -

James T. Corcoran Interviewer: William Hartigan Date of Interview: March 8, 1976 Location: Washington D.C

James T. Corcoran Oral History Interview—3/8/1976 Administrative Information Creator: James T. Corcoran Interviewer: William Hartigan Date of Interview: March 8, 1976 Location: Washington D.C. Length: 18 pages Biographical Note Corcoran, coordinator of advance men for John F. Kennedy’s (JFK) president campaign (1960) and a member of the White House Special Projects staff (1961-1962), discusses advance work on JFK’s November 1963 trip to Texas, conflict within the Texas Democratic Party prior to JFK’s assassination, and JFK’s role as a campaigner for the Democratic Party, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed December 5, 2002, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

This Is Not a Textual Record. This Is Used As an Administrative Marker by the William J

FOIA Number: 2011 -0586-F FOIA MARKER This is not a textual record. This is used as an administrative marker by the William J. Clinton Presidential Library Staff. Collection/Record Group: Clinton Presidential Records Subgroup/Office of Origin: Press Secretary Series/Staff Member: Mike McCurry Subseries: OA/ID Number: 13061 FolderlD: Folder Title: Correspondence Records (A-L) [binder] [4] Stack: Row: Section: Shelf: Position: S 94 3 11 3 Clinton Presidential Records Digital Records Marker This is not a presidential record. This is used as an administrative marker by the William J. Clinton Presidential Library Staff. This marker identifies the place of a tabbed divider. Given our digitization capabilities, we are sometimes unable to adequately scan such dividers. The title from the original document is indicated below. H Divider Title: THE WHI'TE HOUSE WASHINGTON August 14, 1998 Mr. Jon Haber Senior Vice President Fleishman Hillard Suite 1000 1615 L Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036-5610 Dear Jon: You were so kind to write and take note of my announcement. I told the boss that this has been a great if challenging job, but it's one that I'll always be proud I held. I appreciate what you said and I hope you'll keep your eye out for me in the future to make sure I measure up. Many thanks and best wishes. Sincerely, Mike McCurry '11/1/UM-S Press Secretary THE WHITE HOUSE WASH ING rON March 26, 1997 Ms. June Hall Apartment 1 590 South Kane Creek Boulevard Moab, Utah 84532-2500 Dear Ms.