Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47899-1 — Human Figuration and Fragmentation in Preclassic Mesoamerica Julia Guernsey Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-47899-1 — Human Figuration and Fragmentation in Preclassic Mesoamerica Julia Guernsey Index More Information Index Note: Page entries in italics refer to illustrations. absence, representational, 48, 66, 148–149 bench figures, 153, 154, 155, 157, 163 Monument 2, 42–43 Achaemenid palace reliefs, 158 Benjamin, Walter, 85 Monument 16, 34 adornment, personal, 49, 54, 60, 79–80, Berdan, Frances, 100 Monument 17, 33,34 127–128 Bilbao. See Cotzumalguapa Monument 21, 33, 33 Afanador-Pujol, Angélica, 62 Blackman Eddy, Belize, 56, 82 Water Dancing Group (Monuments 11, 8, Aguateca, 83 Blomster, Jeffrey, 45, 48, 52–53, 60, 65, 14, 15, 6, and 7), 32, 32,42 Ajú Álvarez, Gloria, 121 95–96, 101, 121–122 Chalchuapa, 102 Aldana, Gerardo, 130 Boggs, Stanley, 39 figurines at, 82, 121 Altar de Sacrificios, 119 Borgia Codex, 129 sculpture at, 146 Alvaro Obregón sculpture, 23–24 Borhegyi, Stephan de, 152 Monument 12, 38,39 ancestors and lineage formation, 52, 72, 137, Borić,Dušan, 77 Chapman, John, 96, 104 149–150 Bourdieu, Pierre, 16, 62, 123 Cheetham, David, 49–50, 56, 59 Angulo, Jorge, 32, 34, 43 Bove, Frederick, 119 Chesson, Meredith, 45 animal spirit companion. See human–animal Braakhuis, H. E. M., 88, 92, 128 Chiapa de Corzo, 54, 130 relationship Bradley, Richard, 129 figurines at, 57–58, 93 animals, representation of breath and vocalization Chichén Itzá, 103 birds, 30, 51, 74, 76,77 in iconography of animals, 72–74 Chilam Balam book of Maní, 89 coatimundi, 148, 152 mouths as site of, 19, 40, 62–63, 70–72, Chilam Balam of Chumayel, 88 dogs, 30, 76,77 73–74 China, 132, 134 felines, 76, 80, 81 Brittain, Marcus, 104, 106 Chinchilla, Oswaldo, 103, 110 on pedestal sculpture, 150–152, 154, 156 Bronson, Bennet, 134 Chocolá, Monument 1, 89, 91 on pottery, 77–79 Broom, Donald, 165 Christenson, Allen, 91, 100, 108, 129 serpents, 30 Brown, M. -

Megaliths and the Early Mezcala Urban Tradition of Mexico

ICDIGITAL Separata 44-45/5 ALMOGAREN 44-45/2013-2014MM131 ICDIGITAL Eine PDF-Serie des Institutum Canarium herausgegeben von Hans-Joachim Ulbrich Technische Hinweise für den Leser: Die vorliegende Datei ist die digitale Version eines im Jahrbuch "Almogaren" ge- druckten Aufsatzes. Aus technischen Gründen konnte – nur bei Aufsätzen vor 1990 – der originale Zeilenfall nicht beibehalten werden. Das bedeutet, dass Zeilen- nummern hier nicht unbedingt jenen im Original entsprechen. Nach wie vor un- verändert ist jedoch der Text pro Seite, so dass Zitate von Textstellen in der ge- druckten wie in der digitalen Version identisch sind, d.h. gleiche Seitenzahlen (Pa- ginierung) aufweisen. Der im Aufsatzkopf erwähnte Erscheinungsort kann vom Sitz der Gesellschaft abweichen, wenn die Publikation nicht im Selbstverlag er- schienen ist (z.B. Vereinssitz = Hallein, Verlagsort = Graz wie bei Almogaren III). Die deutsche Rechtschreibung wurde – mit Ausnahme von Literaturzitaten – den aktuellen Regeln angepasst. Englischsprachige Keywords wurden zum Teil nach- träglich ergänzt. PDF-Dokumente des IC lassen sich mit dem kostenlosen Adobe Acrobat Reader (Version 7.0 oder höher) lesen. Für den Inhalt der Aufsätze sind allein die Autoren verantwortlich. Dunkelrot gefärbter Text kennzeichnet spätere Einfügungen der Redaktion. Alle Vervielfältigungs- und Medien-Rechte dieses Beitrags liegen beim Institutum Canarium Hauslabgasse 31/6 A-1050 Wien IC-Separatas werden für den privaten bzw. wissenschaftlichen Bereich kostenlos zur Verfügung gestellt. Digitale oder gedruckte Kopien von diesen PDFs herzu- stellen und gegen Gebühr zu verbreiten, ist jedoch strengstens untersagt und be- deutet eine schwerwiegende Verletzung der Urheberrechte. Weitere Informationen und Kontaktmöglichkeiten: institutum-canarium.org almogaren.org Abbildung Titelseite: Original-Umschlag des gedruckten Jahrbuches. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Descargar Este Artículo En Formato

Urban, Patricia, Edward Schortman y Marne Ausec 2000 ¿Poder sin límites?: Los acontecimientos políticos durante el Preclásico Medio en el valle de Naco, Honduras. En XIII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 1999 (editado por J.P. Laporte, H. Escobedo, B. Arroyo y A.C. de Suasnávar), pp.901-920. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala (versión digital). 67 ¿PODER SIN LÍMITES?: LOS ACONTECIMIENTOS POLÍTICOS DURANTE EL PRECLÁSICO MEDIO EN EL VALLE DE NACO, HONDURAS Patricia Urban Edward Schortman Marne Ausec Este ensayo investiga la naturaleza de la complejidad socio-política en el Preclásico Medio (1100-400 AC) en el valle de Naco, al noroeste de Honduras. "Complejidad" es un concepto que consiste de variables cuyas expresiones universales están relacionadas diferencialmente en circunstancias históricas específicas (Feinman y Neitzel 1984; McGuire 1983; de Montmollin 1989; Nelson 1995; Roscoe 1993). Aquí se examinan tres de estas variables según su importancia general para modelar la complejidad y nuestra habilidad de dirigir ciertos aspectos de las variables con la información que tenemos de Naco. La centralización política se refiere hasta qué punto el poder, o la capacidad para ordenar las acciones de otros se concentra en las manos de una sola facción (Balandier 1970; Roscoe 1993:113- 114; Webster 1990). Esta variable se mide por la presencia, dimensión y número de estructuras monumentales (plataformas que tienen por lo menos 1.50 m de altura) fechadas al Preclásico Medio, que se encuentran en los sitios de Naco. El recurso de este criterio se basa en la suposición que el poder mueve a los trabajadores para levantar las estructuras asociadas con los gobernantes aspirantes y los estados que ellos anhelan gobernar. -

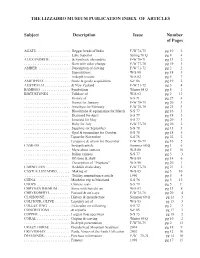

List of Articles

THE LIZZADRO MUSEUM PUBLICATION INDEX OF ARTICLES Subject Description Issue Number of Pages AGATE. .. Beggar beads of India F-W 74-75 pg 10 2 . Lake Superior Spring 70 Q pg 8 4 ALEXANDRITE . & Synthetic alexandrite F-W 70-71 pg 13 2 . Gem with color change F-W 77-78 pg 19 1 AMBER . Description of carving F-W 71-72 pg 2 2 . Superstitions W-S 80 pg 18 5 . in depth treatise W-S 82 pg 5 7 AMETHYST . Stone & geode acquisitions S-F 86 pg 19 2 AUSTRALIA . & New Zealand F-W 71-72 pg 3 4 BAMBOO . Symbolism Winter 68 Q pg 8 1 BIRTHSTONES . Folklore of W-S 93 pg 2 13 . History of S-S 71 pg 27 4 . Garnet for January F-W 78-79 pg 20 3 . Amethyst for February F-W 78-79 pg 22 3 . Bloodstone & aquamarine for March S-S 77 pg 16 3 . Diamond for April S-S 77 pg 18 3 . Emerald for May S-S 77 pg 20 3 . Ruby for July F-W 77-78 pg 20 2 . Sapphire for September S-S 78 pg 15 3 . Opal & tourmaline for October S-S 78 pg 18 5 . Topaz for November S-S 78 pg 22 2 . Turquoise & zircon for December F-W 78-79 pg 16 5 CAMEOS . In-depth article Summer 68 Q pg 1 6 . More about cameos W-S 80 pg 5 10 . Italian cameos S-S 77 pg 3 3 . Of stone & shell W-S 89 pg 14 6 . Description of “Neptune” W-S 90 pg 20 1 CARNELIAN . -

The Toro Historical Review

THE TORO HISTORICAL REVIEW Native Communities in Colonial Mexico Under Spanish Colonial Rule Vannessa Smith THE TORO HISTORICAL REVIEW Prior to World War II and the subsequent social rights movements, historical scholarship on colonial Mexico typically focused on primary sources left behind by Iberians, thus revealing primarily Iberian perspectives. By the 1950s, however, the approach to covering colonial Mexican history changed with the scholarship of Charles Gibson, who integrated Nahuatl cabildo records into his research on Tlaxcala.1 Nevertheless, in his subsequent book The Aztecs under Spanish Rule Gibson went back to predominantly Spanish sources and thus an Iberian lens to his research.2 It was not until the 1970s and 80s that U.S. scholars, under the leadership of James Lockhart, developed a methodology called the New Philology, which focuses on native- language driven research on colonial Mexican history.3 The New Philology has become an important research method in the examination of native communities and the ways in which they changed and adapted to Spanish rule while also holding on to some of their own social and cultural practices and traditions. This historiography focuses on continuities and changes in indigenous communities, particularly the evolution of indigenous socio-political structures and socio-economic relationships under Spanish rule, in three regions of Mexico: Central Mexico, Yucatan, and Oaxaca. Pre-Conquest Community Structure As previously mentioned, Lockhart provided the first scholarship following the New Philology methodology in the United States and applied it to Central Mexico. In his book, The Nahuas After the Conquest, Lockhart lays out the basic structure of Nahua communities in great detail.4 The Nahua, the prominent indigenous group in Central Mexico, organized into communities called altepetl. -

Central America

Zone 1: Central America Martin Künne Ethnologisches Museum Berlin The paper consists of two different sections. The first part has a descriptive character and gives a general impression of Central American rock art. The second part collects all detailed information in tables and registers. I. The first section is organized as follows: 1. Profile of the Zone: environments, culture areas and chronologies 2. Known Sites: modes of iconographic representation and geographic context 3. Chronological sequences and stylistic analyses 4. Documentation and Known Sites: national inventories, systematic documentation and most prominent rock art sites 5. Legislation and institutional frameworks 6. Rock art and indigenous groups 7. Active site management 8. Conclusion II. The second section includes: table 1 Archaeological chronologies table 2 Periods, wares, horizons and traditions table 3 Legislation and National Archaeological Commissions table 4 Rock art sites, National Parks and National Monuments table 5 World Heritage Sites table 6 World Heritage Tentative List (2005) table 7 Indigenous territories including rock art sites appendix: Archaeological regions and rock art Recommended literature References Illustrations 1 Profile of the Zone: environments, culture areas and chronologies: Central America, as treated in this report, runs from Guatemala and Belize in the north-west to Panama in the south-east (the northern Bridge of Tehuantepec and the Yucatan peninsula are described by Mr William Breen Murray in Zone 1: Mexico (including Baja California)). The whole region is characterized by common geomorphologic features, constituting three different natural environments. In the Atlantic east predominates extensive lowlands cut by a multitude of branched rivers. They cover a karstic underground formed by unfolded limestone. -

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT for DISTRIBUTION Figure 0.3

Contents Acknowledgments ix A Brief Note on Usage xiii Introduction: History and Tlaxilacalli 3 Chapter 1: The Rise of Tlaxilacalli, ca. 1272–1454 40 Chapter 2: Acolhua Imperialisms, ca. 1420s–1583 75 Chapter 3: Community and Change in Cuauhtepoztlan Tlaxilacalli, ca. 1544–1575 97 Chapter 4: Tlaxilacalli Religions, 1537–1587 123 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Chapter 5: TlaxilacalliNOT FOR Ascendant, DISTRIBUTION 1562–1613 151 Chapter 6: Communities Reborn, 1581–1692 174 Conclusion: Tlaxilacalli and Barrio 203 List of Acronyms Used Frequently in This Book 208 Bibliography 209 Index 247 vii introduction History and Tlaxilacalli This is the story of how poor, everyday central Mexicans built and rebuilt autono- mous communities over the course of four centuries and two empires. It is also the story of how these self-same commoners constructed the unequal bonds of compul- sion and difference that anchored these vigorous and often beloved communities. It is a story about certain face-to-face human networks, called tlaxilacalli in both singular and plural,1 and about how such networks molded the shape of both the Aztec and Spanish rule.2 Despite this influence, however, tlaxilacalli remain ignored, subordinated as they often were to wider political configurations and most often appearing unmarked—that is, noted by proper name only—in the sources. With care, however, COPYRIGHTEDthe deeper stories of tlaxilacalli canMATERIAL be uncovered. This, in turn, lays bare a root-level history of autonomy and colonialism in central Mexico, told through the powerfulNOT and transformative FOR DISTRIBUTION tlaxilacalli. The robustness of tlaxilacalli over thelongue durée casts new and surprising light on the structures of empire in central Mexico, revealing a counterpoint of weakness and fragmentation in the canonical histories of centralizing power in the region. -

A Mat of Serpents: Aztec Strategies of Control from an Empire in Decline

A Mat of Serpents: Aztec Strategies of Control from an Empire in Decline Jerónimo Reyes On my honor, Professors Andrea Lepage and Elliot King mark the only aid to this thesis. “… the ruler sits on the serpent mat, and the crown and the skull in front of him indicate… that if he maintained his place on the mat, the reward was rulership, and if he lost control, the result was death.” - Aztec rulership metaphor1 1 Emily Umberger, " The Metaphorical Underpinnings of Aztec History: The Case of the 1473 Civil War," Ancient Mesoamerica 18, 1 (2007): 18. I dedicate this thesis to my mom, my sister, and my brother for teaching me what family is, to Professor Andrea Lepage for helping me learn about my people, to Professors George Bent, and Melissa Kerin for giving me the words necessary to find my voice, and to everyone and anyone finding their identity within the self and the other. Table of Contents List of Illustrations ………………………………………………………………… page 5 Introduction: Threads Become Tapestry ………………………………………… page 6 Chapter I: The Sum of its Parts ………………………………………………… page 15 Chapter II: Commodification ………………………………………………… page 25 Commodification of History ………………………………………… page 28 Commodification of Religion ………………………………………… page 34 Commodification of the People ………………………………………… page 44 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………... page 53 Illustrations ……………………………………………………………………... page 54 Appendices ……………………………………………………………………... page 58 Bibliography ……………………………………………………………………... page 60 …. List of Illustrations Figure 1: Statue of Coatlicue, Late Period, 1439 (disputed) Figure 2: Peasant Ritual Figurines, Date Unknown Figure 3: Tula Warrior Figure Figure 4: Mexica copy of Tula Warrior Figure, Late Aztec Period Figure 5: Coyolxauhqui Stone, Late Aztec Period, 1473 Figure 6: Male Coyolxauhqui, carving on greenstone pendant, found in cache beneath the Coyolxauhqui Stone, Date Unknown Figure 7: Vessel with Tezcatlipoca Relief, Late Aztec Period, ca. -

The Bilimek Pulque Vessel (From in His Argument for the Tentative Date of 1 Ozomatli, Seler (1902-1923:2:923) Called Atten- Nicholson and Quiñones Keber 1983:No

CHAPTER 9 The BilimekPulqueVessel:Starlore, Calendrics,andCosmologyof LatePostclassicCentralMexico The Bilimek Vessel of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Vienna is a tour de force of Aztec lapidary art (Figure 1). Carved in dark-green phyllite, the vessel is covered with complex iconographic scenes. Eduard Seler (1902, 1902-1923:2:913-952) was the first to interpret its a function and iconographic significance, noting that the imagery concerns the beverage pulque, or octli, the fermented juice of the maguey. In his pioneering analysis, Seler discussed many of the more esoteric aspects of the cult of pulque in ancient highland Mexico. In this study, I address the significance of pulque in Aztec mythology, cosmology, and calendrics and note that the Bilimek Vessel is a powerful period-ending statement pertaining to star gods of the night sky, cosmic battle, and the completion of the Aztec 52-year cycle. The Iconography of the Bilimek Vessel The most prominent element on the Bilimek Vessel is the large head projecting from the side of the vase (Figure 2a). Noting the bone jaw and fringe of malinalli grass hair, Seler (1902-1923:2:916) suggested that the head represents the day sign Malinalli, which for the b Aztec frequently appears as a skeletal head with malinalli hair (Figure 2b). However, because the head is not accompanied by the numeral coefficient required for a completetonalpohualli Figure 2. Comparison of face date, Seler rejected the Malinalli identification. Based on the appearance of the date 8 Flint on front of Bilimek Vessel with Aztec Malinalli sign: (a) face on on the vessel rim, Seler suggested that the face is the day sign Ozomatli, with an inferred Bilimek Vessel, note malinalli tonalpohualli reference to the trecena 1 Ozomatli (1902-1923:2:922-923). -

Rethinking the Conquest : an Exploration of the Similarities Between Pre-Contact Spanish and Mexica Society, Culture, and Royalty

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2015 Rethinking the Conquest : an exploration of the similarities between pre-contact Spanish and Mexica society, culture, and royalty Samantha Billing University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2015 Samantha Billing Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Billing, Samantha, "Rethinking the Conquest : an exploration of the similarities between pre-contact Spanish and Mexica society, culture, and royalty" (2015). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 155. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/155 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by SAMANTHA BILLING 2015 All Rights Reserved RETHINKING THE CONQUEST: AN EXPLORATION OF THE SIMILARITIES BETWEEN PRE‐CONTACT SPANISH AND MEXICA SOCIETY, CULTURE, AND ROYALTY An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Samantha Billing University of Northern Iowa May 2015 ABSTRACT The Spanish Conquest has been historically marked by the year 1521 and is popularly thought of as an absolute and complete process of indigenous subjugation in the New World. Alongside this idea comes the widespread narrative that describes a barbaric, uncivilized group of indigenous people being conquered and subjugated by a more sophisticated and superior group of Europeans. -

Pre-Classic: Olmec

Pre-Classic: Olmec Monday, September 17, 12 Pre-Classic: Olmec The Olmec Heartland Monday, September 17, 12 Pre-Classic: Olmec Earliest writing in Mesoamerica can be found here on Stela C of the Olmec city of Tres Zapotes. The glyphs give the date of 32 bce. Olmec religion based on the were-jaguar had few rivals in being bizarre. Monday, September 17, 12 Pre-Cl Pre-Classic: Olmec The Major Olmec Site Was La Venta Plan of LaVenta Monday, September 17, 12 Pre-Cl Pre-Classic: Olmec Ceremonial Zone Pyramid of LaVenta Monday, September 17, 12 Pre-Classic: Olmec This tomb, made of carved basalt columns, was constructed in a cavity carved into an existing mound. Inside were two coffins of two youths and jadeite and hematite sculptures. Plan of LaVenta Monday, September 17, 12 Pre-Classic: Olmec Jaguar Mask Floor Mosaic Monday, September 17, 12 Pre-Classic: Olmec Jaguar Mask Floor Mosaic Monday, September 17, 12 Pre-Classic: Olmec Jaguar Floor Mask Mosaic Monday, September 17, 12 Pre-Classic: Olmec Jaguar Floor Mask Mosaic Monday, September 17, 12 Pre-Classic: Olmec Artist’s Reconstruction of Building the Floor Mask Jaguar Floor Mask Mosaic Monday, September 17, 12 Pre-Classic: Olmec Offering #4 Monday, September 17, 12 Pre-Classic: Olmec In this grouping of 16 figures, 13 are of serpentine, 2 of Jade, and 1 of red sandstone. They stand before 6 jade celts. Offering #4 Monday, September 17, 12 Pre-Classic: Olmec Colossal Head Monday, September 17, 12 Pre-Classic: Olmec Colossal Head Monday, September 17, 12 Pre-Classic: Olmec Colossal Head Monday,