The-Structurality-Of-Poststructure.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Earogenous Zones

234 Index Index Note: Film/DVD titles are in italics; album titles are italic, with ‘album’ in parentheses; song titles are in quotation marks; book titles are italic; musical works are either in italics or quotation marks, with composer’s name in parentheses. A Rebours (Huysmans) 61 Asimov, Isaac 130 Abducted by the Daleks/Daloids 135 Assault on Precinct 13 228 Abe, Sada 91–101 Astaire, Fred 131 Abrams, J. 174 Astley, Edwin 104 Abu Ghraib 225, 233 ‘Astronomy Domine’ 81, 82 acousmêtre 6 Atkins, Michael 222 Acre, Billy White, see White Acre, Billy Augoyard, J.-F. 10 Adamson, Al 116 Aury, Dominique (aka Pauline Reage) 86 affect 2, 67, 76 Austin, Billy 215 African music 58 Austin Powers movies 46 Age of Innocence, The 64 Australian Classification Board 170 Ai no borei (‘Empire of Passion’) 100–1 Avon Science Fiction Reader (magazine) 104 Ai no korida (In the Realm of the Senses) 1, 4, Avon Theater, New York 78 7, 89–101 Aihara, Kyoko 100 ‘Baby Did A Bad Bad Thing’ 181–2 Algar, James 20 Bacchus, John 120, 128, 137 Alice in Wonderland (Lewis Carroll) 5, 70, 71, Bach, Johann Sebastian 62 74, 76, 84, 116 Bachelet, Pierre 68, 71, 72, 74 Alien 102 Bacon, Francis 54 Alien Probe 129 Bailey, Fenton 122, 136 Alien Probe II 129 Baker, Jack 143, 150 Alpha Blue 117–19, 120 Baker, Rick 114 Also sprach Zarathustra (Richard Strauss) 46, 112, Ballard, Hank, and the Midnighters 164 113 Band, Charles 126 Altman, Rick 2, 9, 194, 199 Bangs, Lester 141 Amateur Porn Star Killer 231 banjo 47 Amazing Stories (magazine) 103, 104 Barbano, Nicolas 35, 36 Amelie 86 Barbarella 5, 107–11, 113, 115, 119, 120, American National Parent/Teacher Association 147 122, 127, 134, 135, 136 Ampeauty (album) 233 Barbato, Randy 122, 136 Anal Cunt 219 Barbieri, Gato 54, 55, 57 … And God Created Woman, see Et Dieu créa Bardot, Brigitte 68, 107–8 la femme Barker, Raphael 204 Andersen, Gotha 32 Baron, Red 79 Anderson, Paul Thomas 153, 158 Barr, M. -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

Smart Cinema As Trans-Generic Mode: a Study of Industrial Transgression and Assimilation 1990-2005

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DCU Online Research Access Service Smart cinema as trans-generic mode: a study of industrial transgression and assimilation 1990-2005 Laura Canning B.A., M.A. (Hons) This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of Ph.D in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. November 2013 School of Communications Supervisor: Dr. Pat Brereton 1 I hereby certify that that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Ph.D is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed:_________________________________ (Candidate) ID No.: 58118276 Date: ________________ 2 Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction p.6 Chapter Two: Literature Review p.27 Chapter Three: The industrial history of Smart cinema p.53 Chapter Four: Smart cinema, the auteur as commodity, and cult film p.82 Chapter Five: The Smart film, prestige, and ‘indie’ culture p.105 Chapter Six: Smart cinema and industrial categorisations p.137 Chapter Seven: ‘Double Coding’ and the Smart canon p.159 Chapter Eight: Smart inside and outside the system – two case studies p.210 Chapter Nine: Conclusions p.236 References and Bibliography p.259 3 Abstract Following from Sconce’s “Irony, nihilism, and the new American ‘smart’ film”, describing an American school of filmmaking that “survives (and at times thrives) at the symbolic and material intersection of ‘Hollywood’, the ‘indie’ scene and the vestiges of what cinephiles used to call ‘art films’” (Sconce, 2002, 351), I seek to link industrial and textual studies in order to explore Smart cinema as a transgeneric mode. -

The Origin of Love Tour Songs and Stories of Hedwig with Special Guest Amber Martin Featuring the Songs of Hedwig by Stephen Trask Produced by Arktype

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CAP UCLA presents John Cameron Mitchell The Origin Of Love Tour Songs and Stories of Hedwig With special guest Amber Martin Featuring the songs of Hedwig by Stephen Trask Produced by ArKtype April 11 at The Theatre at Ace Hotel, DTLA “The Origin of Love [is] a punk-rock live behind the music episode of sorts and a gift to Hedwig heads everywhere.” — DC Theatre Scene UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance (CAP UCLA) presents John Cameron Mitchell’s The Origin Of Love Tour on Saturday, April 11, at The Theatre at Ace Hotel in Downtown LA. Tickets starting at $28 are available now at cap.ucla.edu, 310-825-2101 and the Royce Hall box office. The Origin of Love Tour investigates Hedwig and The Angry Inch’s origins following 25- years of worldwide influence as one of alt-culture’s most beloved and enduring creations, and John Cameron Mitchell’s ideas and relationships to show business. In addition to songs from the gender-bending rock musical that opened off-Broadway in 1998, released as an acclaimed film in 2001, won the Tony Award for best musical revival in 2014, and has spawned legions of adoring “Hed-Head’s” worldwide, the audience will learn about Mitchell’s rebellion against Broadway tropes, meeting songwriter Trask and his beloved bandmember Jack who became his boyfriend, growing up queer in a military family, Platonic and Gnostic Christian philosophy and its connection to non- binary gender expression, and the influence of Lou Reed and David Bowie. Mitchell also performs songs from his podcast series Anthem: Homunculus and his last film, the punk-era How to Talk to Girls at Parties, as well as his recent acclaimed EP of Lou Reed covers with Eyelids and Peter Buck entitled “Turning Time Around.” New York Vocalist, Cabaret Star and Comedic Monologist Amber Martin joins Mitchell along with very special guests in this rousing performance. -

Uk / 2018 / 1.66 / 5.1

HIGH LIFE 110 min / Germany – France – USA – Poland – UK / 2018 / 1.66 / 5.1 EVA DIEDERIX [email protected] SILVIA SIMONUTTI [email protected] FANNY BEAUVILLE [email protected] OLPHA BEN SALAH [email protected] PHOTOS AND PRESS KIT CAN BE DOWNLOADED FROM https://www.wildbunch.biz/movie/high-life/ Deep space. Monte and his daughter Willow live together aboard a spacecraft, in complete isolation. A man whose strict self-discipline is a shield against desire, Monte fathered her against his will. His sperm was used to inseminate the young woman who gave birth to her. They were members of a crew of prisoners – death row inmates. Guinea pigs sent on a mission. Now only Monte and Willow remain. Through his daughter, he experiences the birth of an all-powerful love. Together, father and daughter approach their destination – the black hole in which time and space cease to exist. How did High Life come about? A while back, an English producer asked me if I wanted to participate in a collection of films called Femmes Fatales. At first, I wasn’t that interested, but after thinking it over, I agreed. The project took ages to get off the ground. There was no money. It took 6 or 7 years to hammer out a coproduction: France, Germany, Poland and eventually America. During that time, I went to England and the States to meet with actors. The actor I dreamed of for the lead role of Monte was Philip Seymour Hoffman, because of his age, his weariness – but he died mid- route. -

Ethics and Politics in New Extreme Films

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online ETHICS AND POLITICS IN NEW EXTREME FILMS Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Oliver Kenny Department of Film Queen Mary University of London I, Oliver Kenny, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the elec- tronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information de- rived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 20th December 2017 2 Abstract This thesis investigates a corpus of controversial, mainly European films from 1998 to 2013, to determine which features have led to their critical description as ‘new extreme’ films and according to what ethical framework ‘new extreme’ films operate. -

Between the Gothic and Surveillance: Gay (Male) Identity, Fiction Film, and Pornography (1970-2015)

Between the Gothic and Surveillance: Gay (Male) Identity, Fiction Film, and Pornography (1970-2015) Evangelos Tziallas A Thesis In the Department of The Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Moving Image Studies Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada October 2015 © Evangelos Tziallas, 2015 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis is prepared By: Evangelos Tziallas Entitled: Between the Gothic and Surveillance: Gay (Male) Identity, Fiction Film, and Pornography (1970-2015) and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Film and Moving Image Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: Chair Amy Swifen Examiner John Mercer Examiner Ara Osterweil Examiner Juliann Pidduck Supervisor Thomas Waugh Approved by Chair of Department of Graduate Program Director 2015 Dean of Faculty Abstract Between the Gothic and Surveillance: Gay (Male) Identity, Fiction Film, and Pornography (1970-2015) Evangelos Tziallas, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2015 In this thesis I make the case for rethinking fictional and explicit queer representation as a form of surveillance. I put recent research in surveillance studies, particularly work on informational doubling, in conversation with the concepts of the uncanny and the doppelgänger to reconsider the legacy of screen theory and cinematic discipline in relation to the ongoing ideological struggle between normativity and queerness. I begin my investigation in and around the Stonewall era examining the gothic roots and incarnation of gay identity. -

Kataloga Društvo ŠKUC, Metelkova 6, Ljubljana Tel

Ljubljana, Celje, Koper 24. 11. - 2. 12. 2007 ¦ Go East Igor Španjol »Vse to je zaradi ameriških filmov!« kriči obupana Rana, ko ji brat Ašraf v filmu Milni mehurček (Ha’bua, 2006) razkrije, da je gej. Tragedija je toliko večja, ker je Ašraf Palestinec, njegov fant Noam pa Izraelec. Vendar Rana ima prav vsaj iz dveh vidikov. Na intimni ravni namreč verjame, da se lahko človeka, ko se enkrat znajde sam v mraku kinodvorane, soočen z enigmo svoje seksualnosti, določene filmske pripovedi tako dotaknejo, da mu spremenijo potek dejanj in morda celo življenje. Bratovo zgodbo razume kot dokaz, da umetnost lahko spreminja stanja naše zavesti. Zaradi opazovanja stanj filmskih junakov med gledanjem filmov tudi sami postanemo ranljivi in tako hkrati močnejši. Lastne svetove soočamo s svetovi in načini razmišljanja junakinj in junakov, poskušamo razumeti, zakaj se odločajo za neko ravnanje. Rana bolj kot v moč političnega diskurza in njegovih diverzij verjame v male stvari in vsakdanje zgodbe. In prav te nam v gejevskih in lezbičnih filmih pogosto dajejo največ misliti. Kljub temu se Rana postavi tudi nasproti dominantnim in stereotipnim medijskim podobam zaho- dnega žanrskega filma in strahovitim političnim posledicam, ki jih te lahko porajajo. Zato letos predvajamo nezahodne, na prvi pogled fabulativno in tehnično manj dovršene filme. Zavedamo se, da imajo različne kulture različne produkcijske pogoje in različne pripovedne načine. Če se režiser/ka odloči za nelinearno pripoved, naturščike, naravno svetlobo, statično kamero in avtentična snemalna prizorišča, so to tudi strateške odločitve, ki kažejo na kreativne presežke, ne pa nedovršenosti. S temi prijemi želi v film vključi- ti pripovedne načine, značilne za svojo neposredno skupnost in jo tako narediti za aktivno pripovedovalko lastne zgodovine. -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit “Utopian Contemporaries: Queer Temporality and America” Verfasser Leopold Lippert angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, im November 2008 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Diplomstudium Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuerin: Univ.-Doz. Dr. Astrid Fellner Hinweis Diese Diplomarbeit hat nachgewiesen, dass die betreffende Kandidatin oder der betreffende Kandidat befähigt ist, wissenschaftliche Themen selbstständig sowie inhaltlich und methodisch vertretbar zu bearbeiten. Da die Korrekturen der/des Beurteilenden nicht eingetragen sind und das Gutachten nicht beiliegt, ist daher nicht erkenntlich, mit welcher Note diese Arbeit abgeschlossen wurde. Das Spektrum reicht von sehr gut bis genügend. Es wird gebeten, diesen Hinweis bei der Lektüre zu beachten. UTOPIAN CONTEMPORARIES: QUEER TEMPORALITY AND AMERICA Leopold Lippert TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements Introduction 1 1. The Willingness to Insist That the Future Start Here 9 2. Life in the Memory of One Who No Longer Lives 31 3. Transcending the Discipline of the Service 51 4. Blackout: Utopian Contemporaries 71 Conclusion 91 Bibliography 95 Index 107 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The fact that my name, and my name only, graces the cover page of this thesis is, to say the very least, an oversimplification. The following study emerges out of the numerous conversations I have had with friends and colleagues over the last year. Consequently, I have to thank many people who offered me the invaluable gifts of an open ear, an open mind, and an open heart. First and foremost, I am grateful to Astrid Fellner, my thesis advisor, for her consistently generous and intensive engagement with my work. -

First Friday News & Views

MARCH 2008 First Friday VOLUME 13 News & Views ISSUE THE 3 MONTHLY NEWSLETTER No Impeachment OF THE No Pardon FIRST FRIDAY by Jonathan Wilson BREAKFAST CLUB, INC. here has been talk of impeachment, and more than one member of Congress has co-sponsored legislation to that INSIDE end, Dennis Kucinich chief among them. Certainly there are ample grounds for pursuing impeachment, whether or not a Tconviction would follow. The US Constitution provides that remedy Briefs & Shorts 2 as the ultimate check on an errant executive or judicial officeholder. If there’s reason to believe that a high crime or misdemeanor has been Movie Review by Gary 3 committed, an officerholder can be “impeached” by the House of Kaufman Representatives and tried before the Senate. If convicted, the office- holder is removed from office. As far out as such a remedy would February Speaker Re- 4 appear to be, I never thought I’d live to see the attempt made against view by Bruce Carr anyone. Yet those merely ten years old today were alive to see it tried Jonathan Wilson against President Clinton for shading the truth and parsing his words From the Editor 6 about an illicit liaison with Monica Lewinsky. That’s something, by the way, that cheating hus- bands have been doing for literally centuries. If supposedly lying about getting laid is grounds for impeachment, there is more than enough evidence of real crimes to pursue the impeachment of the current occupant of the White House. No one of consequence has suffered any consequences for leaking a CIA operative’s identity; secret prisons all over the world; or extra-ordinary renditions for no other conceivable reason than surrogate torture, a war crime. -

Hfl60-Web.Pdf

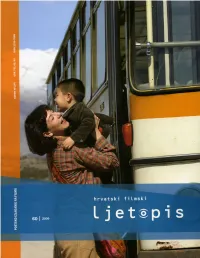

hhrvatskirvatski ffilmskiilmski lljetopisjetopis god. 15 (2009) broj 60, zima 2009. Hrvatski fi lmski ljetopis utemeljili su 1995. Hrvatsko društvo fi lmskih kritičara, Hrvatska kinoteka i Filmoteka 16 Utemeljiteljsko uredništvo: Vjekoslav Majcen, Ivo Škrabalo i Hrvoje Turković Časopis je evidentiran u FIAF International Index to Film Periodicals i u Arts and Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI) Uredništvo / Editorial Board: Bruno Kragić (glavni urednik / editor-in-chief) Hrvoje Turković (odgovorni urednik / supervising editor) Tomislav Šakić (izvršni urednik / managing editor) Nikica Gilić Krešimir Košutić (repertoar i festivali / new films and festivals) Suradnici/Contributors: Ana Brnardić (lektorski savjeti / proof reading) Juraj Kukoč (kronika/chronicles) Sandra Palihnić (prijevod sažetaka / translation of summaries) Duško Popović (bibliografije/bibliographies) Anka Ranić (UDK) Dizajn/Design: Barbara Blasin Naslovnica/Cover: Darija Lorenci, Oprosti za kung fu (O. Sviličić, 2004) Stražnje korice / Back cover: Vedran Šamanović (Arhiv HFS-a) Nakladnik/Publisher: Hrvatski filmski savez Za nakladnika / Publishing Manager: Vera Robić-Škarica ([email protected]) Priprema za tisak / Prepress: Kolumna d.o.o., Zagreb Tisak / Printed By: Tiskara CB Print, Samobor Adresa/Contact: Hrvatski filmski savez (za Hrvatski filmski ljetopis), HR-10000 Zagreb, Tuškanac 1 telefon/phone: (385) 01 / 4848771 telefaks/fax: (385) 01 / 4848764 e-mail uredništva: [email protected] / [email protected] www.hfs.hr Izlazi tromjesečno u nakladi od 1000 primjeraka Cijena: 50 kn / Godišnja pretplata: 150 kn Žiroračun: Zagrebačka banka, 2360000-1101556872, Hrvatski filmski savez (s naznakom “za Hrvatski filmski ljetopis”) Hrvatski filmski ljetopis is published quarterly by Croatian Film Clubs’ Association Subscription abroad: 60 € / Account: 2100058638/070 S.W.I.F.T. HR 2X Godište 15. -

Aleix Martinez Interviewer: Kristyn Scorsone Date: September 6, 2017 Location: Rutgers University-Newark

Queer Newark Oral History Project Interviewee: Aleix Martinez Interviewer: Kristyn Scorsone Date: September 6, 2017 Location: Rutgers University-Newark Kristyn: Today is September 6, 2017. My name is Kristyn Scorsone and I’m interviewing Aleix Martinez in the Queer Newark Office at Rutgers Newark. First off, thank you for doing this. Aleix: Thank you so much for having me. Kristyn: The first question is when and where were you born? Aleix: I was born just outside of Barcelona, Spain on July 20th, 1978, which is the day of the moon landing but not the same year. [Laughter] I lived there in the Barcelona area until April 1984, which is when I first came to Newark. Kristyn: Who raised you? Aleix: I was raised by my mother and father, but like most kids of my generation I was a latchkey kid, so I’d be home alone until 8:00 at night so I wanna say I also raised me [laughter] part of the time. Kristyn: What did your parents do for a living? Aleix: My mom at the time was working retail here in Newark in Ironbound at a Spanish clothing store and my dad worked in Kearny at a water purifying plant called Spectraserv. My mom eventually started working at Port Newark as a security guard. Kristyn: What’s an early memory that stands out to you? Aleix: Of Newark? Kristyn: Well, in general. Aleix: I remember the first day that I landed in the United States is a huge memory for me. I remember that the Empire State Building was yellow and I remember driving over the Verrazano and I remember telling my mom I was like, “Is this New York?” and she was like, “Yeah, this is New York.” I was like, “I don’t like it.