Ethics and Politics in New Extreme Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foster, Morgan with TP.Pdf

Foster To my parents, Dawn and Matt, who filled our home with books, music, fun, and love, and who never gave me any idea I couldn’t do whatever I wanted to do or be whoever I wanted to be. Your love, encouragement, and support have helped guide my way. ! ii! Foster ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Roberta Maguire for her priceless guidance, teaching, and humor during my graduate studies at UW-Oshkosh. Her intellectual thoroughness has benefitted me immeasurably, both as a student and an educator. I would also like to thank Dr. Don Dingledine and Dr. Norlisha Crawford, whose generosity, humor, and friendship have helped make this project not only feasible, but enjoyable as well. My graduate experience could not have been possible without all of their support, assistance, and encouragement. ! iii! Foster TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction..........................................................................................................................v History of African American Children’s and Young Adult Literature ......................... vi The Role of Early Libraries and Librarians.....................................................................x The New Breed............................................................................................................ xiv The Black Aesthetic .................................................................................................... xvi Revelation, Not Revolution: the Black Arts Movement’s Early Influence on Virginia Hamilton’s Zeely ............................................................................................................1 -

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 85,810 Abstract Extreme art cinema, has, in recent film scholarship, become an important area of study. Many of the existing practices are motivated by a Franco-centric lens, which ultimately defines transgressive art cinema as a new phenomenon. The thesis argues that a study of extreme art cinema needs to consider filmic production both within and beyond France. It also argues that it requires an historical analysis, and I contest the notion that extreme art cinema is a recent mode of Film production. The study considers extreme art cinema as inhabiting a space between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms, noting the slippage between the two often polarised industries. The study has a focus on the paratext, with an analysis of DVD extras including ‘making ofs’ and documentary featurettes, interviews with directors, and cover sleeves. This will be used to examine audience engagement with the artefacts, and the films’ position within the film market. Through a detailed assessment of the visual symbols used throughout the films’ narrative images, the thesis observes the manner in which they engage with the taste structures and pictorial templates of art and exploitation cinema. -

Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South

Antoni Górny Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South Abstract: The so-called blaxploitation genre – a brand of 1970s film-making designed to engage young Black urban viewers – has become synonymous with channeling the political energy of Black Power into larger-than-life Black characters beating “the [White] Man” in real-life urban settings. In spite of their urban focus, however, blaxploitation films repeatedly referenced an idea of the South whose origins lie in antebellum abolitionist propaganda. Developed across the history of American film, this idea became entangled in the post-war era with the Civil Rights struggle by way of the “race problem” film, which identified the South as “racist country,” the privileged site of “racial” injustice as social pathology.1 Recently revived in the widely acclaimed works of Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained) and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), the two modes of depicting the South put forth in blaxploitation and the “race problem” film continue to hold sway to this day. Yet, while the latter remains indelibly linked, even in this revised perspective, to the abolitionist vision of emancipation as the result of a struggle between idealized, plaintive Blacks and pathological, racist Whites, blaxploitation’s troping of the South as the fulfillment of grotesque White “racial” fantasies offers a more powerful and transformative means of addressing America’s “race problem.” Keywords: blaxploitation, American film, race and racism, slavery, abolitionism The year 2013 was a momentous one for “racial” imagery in Hollywood films. Around the turn of the year, Quentin Tarantino released Django Unchained, a sardonic action- film fantasy about an African slave winning back freedom – and his wife – from the hands of White slave-owners in the antebellum Deep South. -

LAUREN BLISS the Cinematic Body in View of the Antipodes: Philip Brophy's Body Melt As the Bad Copy

Lauren Bliss, The Cinematic Body in View of the Antipodes: Philip Brophy’s Body Melt as the bad copy LAUREN BLISS The Cinematic Body in View of the Antipodes: Philip Brophy’s Body Melt as the bad copy ABSTRACT Through a wide ranging study of Philip Brophy's academic and critical writings on horror cinema, this essay considers how Brophy's theory of the spectator's body is figured in his only horror feature Body Melt (1993). Body Melt is noteworthy insofar as it poorly copies a number of infamous sequences from classical horror films of the 1970s and 1980s, a form of figuration that this essay will theorise as distinctly Antipodean. Body Melt will be related as an antagonistic 'turning inside out' of the subjectivity of the horror movie spectator, which will be read in the light of both the usurped subject of semiotic film theory, and the political aesthetics of Australian exploitation cinema. Philip Brophy’s Body Melt, made in 1993, is a distinctly antipodean film: it not only copies scenes from classic horror movies such as The Hills Have Eyes (1977), Alien (1979), The Thing (1982) and Scanners (1981), it also copies the scenes badly. Such copying plays on and illuminates the ‘rules’ of horror as the toying with and preying upon the spectator’s expectation of fear. Brophy’s own theory of horror, written across a series of essays in academic and critical contexts between the 1980s and the 1990s, considers the peculiarity of the spectator’s body in the wake of the horror film. It relates that the seemingly autonomic or involuntary response of fear or suspense that horror movies induce in a viewer is troubled by the fact that both film and viewer knowingly intend this response to occur from the very beginning. -

Earogenous Zones

234 Index Index Note: Film/DVD titles are in italics; album titles are italic, with ‘album’ in parentheses; song titles are in quotation marks; book titles are italic; musical works are either in italics or quotation marks, with composer’s name in parentheses. A Rebours (Huysmans) 61 Asimov, Isaac 130 Abducted by the Daleks/Daloids 135 Assault on Precinct 13 228 Abe, Sada 91–101 Astaire, Fred 131 Abrams, J. 174 Astley, Edwin 104 Abu Ghraib 225, 233 ‘Astronomy Domine’ 81, 82 acousmêtre 6 Atkins, Michael 222 Acre, Billy White, see White Acre, Billy Augoyard, J.-F. 10 Adamson, Al 116 Aury, Dominique (aka Pauline Reage) 86 affect 2, 67, 76 Austin, Billy 215 African music 58 Austin Powers movies 46 Age of Innocence, The 64 Australian Classification Board 170 Ai no borei (‘Empire of Passion’) 100–1 Avon Science Fiction Reader (magazine) 104 Ai no korida (In the Realm of the Senses) 1, 4, Avon Theater, New York 78 7, 89–101 Aihara, Kyoko 100 ‘Baby Did A Bad Bad Thing’ 181–2 Algar, James 20 Bacchus, John 120, 128, 137 Alice in Wonderland (Lewis Carroll) 5, 70, 71, Bach, Johann Sebastian 62 74, 76, 84, 116 Bachelet, Pierre 68, 71, 72, 74 Alien 102 Bacon, Francis 54 Alien Probe 129 Bailey, Fenton 122, 136 Alien Probe II 129 Baker, Jack 143, 150 Alpha Blue 117–19, 120 Baker, Rick 114 Also sprach Zarathustra (Richard Strauss) 46, 112, Ballard, Hank, and the Midnighters 164 113 Band, Charles 126 Altman, Rick 2, 9, 194, 199 Bangs, Lester 141 Amateur Porn Star Killer 231 banjo 47 Amazing Stories (magazine) 103, 104 Barbano, Nicolas 35, 36 Amelie 86 Barbarella 5, 107–11, 113, 115, 119, 120, American National Parent/Teacher Association 147 122, 127, 134, 135, 136 Ampeauty (album) 233 Barbato, Randy 122, 136 Anal Cunt 219 Barbieri, Gato 54, 55, 57 … And God Created Woman, see Et Dieu créa Bardot, Brigitte 68, 107–8 la femme Barker, Raphael 204 Andersen, Gotha 32 Baron, Red 79 Anderson, Paul Thomas 153, 158 Barr, M. -

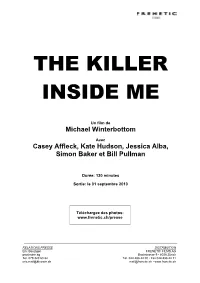

The Killer Inside Me

THE KILLER INSIDE ME Un film de Michael Winterbottom Avec Casey Affleck, Kate Hudson, Jessica Alba, Simon Baker et Bill Pullman Durée: 120 minutes Sortie: le 01 septembre 2010 Téléchargez des photos: www.frenetic.ch/presse RELATIONS PRESSE DISTRIBUTION Eric Bouzigon FRENETIC FILMS AG prochaine ag Bachstrasse 9 • 8038 Zürich Tél. 079 320 63 82 Tél. 044 488 44 00 • Fax 044 488 44 11 [email protected] [email protected] • www.frenetic.ch SYNOPSIS Based on the novel by legendary pulp writer Jim Thompson, Michael Winterbottom’s THE KILLER INSIDE ME tells the story of handsome, charming, unassuming small town sheriff’s deputy Lou Ford. Lou has a bunch of problems. Woman problems. Law enforcement problems. An ever-growing pile of murder victims in his west Texas jurisdiction. And the fact he’s a sadist, a psychopath, a killer. Suspicion begins to fall on Lou, and it’s only a matter of time before he runs out of alibis. But in Thompson’s savage, bleak, blacker than noir universe nothing is ever what it seems, and it turns out that the investigators pursuing him might have a secret of their own. CAST Lou Ford.........................................................................................................................................CASEY AFFLECK Joyce Lakeland ..................................................................................................................................JESSICA ALBA Amy Stanton..................................................................................................................................... -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

Metropolis Filmelméleti És Filmtörténeti Folyóirat 20. Évf. 3. Sz. (2016/3.)

900 Ft 2016 03 Filmfesztiválok filmelméleti és filmtörténeti folyóirat 2016 3. szám Filmfesztiválok Fahlenbrach8_Layout 1 2016.05.08. 4:13 Page 26 c[jhefeb_i <_bc[bcb[j_ i \_bcjhjd[j_ \ebo_hWj t a r t a l o m XX. évfolyam 3. szám A szerkesztõbizottság Filmfesztiválok tagjai: Bíró Yvette 6 Fábics Natália: Bevezetõ a Filmfesztiválok összeállításhoz Gelencsér Gábor Hirsch Tibor 8 Thomas Elsaesser: A filmfesztiválok hálózata Király Jenõ A filmmûvészet új európai topográfiája Kovács András Bálint Fábics Natália fordítása A szerkesztôség tagjai: 28 Dorota Ostrowska: A cannes-i filmfesztivál filmtörténeti szerepe Vajdovich Györgyi Fábics Natália fordítása Varga Balázs Vincze Teréz 40 Varga Balázs: Presztízspiacok Filmek, szerzõk és nemzeti filmkultúrák a nemzetközi A szám szerkesztõi: fesztiválok kortárs hálózatában Fábics Natália Varga Balázs 52 Fábics Natália: Vér és erõszak nélkül a vörös szõnyegen Takashi Miike, az ázsiai mozi rosszfiújának átmeneti Szerkesztõségi munkatárs: domesztikálódása Jordán Helén 60 Orosz Anna Ida: Az animációsfilm-mûvészet védõbástyái Korrektor: Jagicza Éva 67 Filmfesztiválok — Válogatott bibliográfia Szerkesztõség: 1082 Bp., Horváth Mihály tér 16. K r i t i k a Tel.: 06-20-483-2523 (Jordán Helén) 72 Árva Márton: Paul A. Schroeder Rodríguez: Latin American E-mail: [email protected] Cinema — A Comparative History Felelõs szerkesztõ: 75 Szerzõink Vajdovich Györgyi ISSN 1416-8154 Kiadja: Számunk megjelenéséhez segítséget nyújtott Kosztolányi Dezsõ Kávéház a Nemzeti Kulturális Alap. Kulturális Alapítvány Felelõs kiadó: Varga Balázs Terjesztõ: Holczer Miklós [email protected] 36-30-932-8899 Arculatterv: Szász Regina és Szabó Hevér András Tördelõszerkesztõ: Zrinyifalvi Gábor Borítóterv és KÖVETKEZÕ SZÁMUNK TÉMÁJA: nyomdai elõkészítés: Atelier Kft. FÉRFI ÉS NÕI SZEREPEK A MAGYAR FILMBEN Nyomja: X-Site.hu Kft. -

9 SONGS-B+W-TOR

9 SONGS AFILMBYMICHAEL WINTERBOTTOM One summer, two people, eight bands, 9 Songs. Featuring exclusive live footage of Black Rebel Motorcycle Club The Von Bondies Elbow Primal Scream The Dandy Warhols Super Furry Animals Franz Ferdinand Michael Nyman “9 Songs” takes place in London in the autumn of 2003. Lisa, an American student in London for a year, meets Matt at a Black Rebel Motorcycle Club concert in Brixton. They fall in love. Explicit and intimate, 9 SONGS follows the course of their intense, passionate, highly sexual affair, as they make love, talk, go to concerts. And then part forever, when Lisa leaves to return to America. CAST Margo STILLEY AS LISA Kieran O’BRIEN AS MATT CREW DIRECTOR Michael WINTERBOTTOM DP Marcel ZYSKIND SOUND Stuart WILSON EDITORS Mat WHITECROSS / Michael WINTERBOTTOM SOUND EDITOR Joakim SUNDSTROM PRODUCERS Andrew EATON / Michael WINTERBOTTOM EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Andrew EATON ASSOCIATE PRODUCER Melissa PARMENTER PRODUCTION REVOLUTION FILMS ABOUT THE PRODUCTION IDEAS AND INSPIRATION Michael Winterbottom was initially inspired by acclaimed and controversial French author Michel Houellebecq’s sexually explicit novel “Platform” – “It’s a great book, full of explicit sex, and again I was thinking, how come books can do this but film, which is far better disposed to it, can’t?” The film is told in flashback. Matt, who is fascinated by Antarctica, is visiting the white continent and recalling his love affair with Lisa. In voice-over, he compares being in Antarctica to being ‘two people in a bed - claustrophobia and agoraphobia in the same place’. Images of ice and the never-ending Antarctic landscape are effectively cut in to shots of the crowded concerts. -

Reality Is Broken a Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World E JANE Mcgonigal

Reality Is Broken a Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World E JANE McGONIGAL THE PENGUIN PRESS New York 2011 ADVANCE PRAISE FOR Reality Is Broken “Forget everything you know, or think you know, about online gaming. Like a blast of fresh air, Reality Is Broken blows away the tired stereotypes and reminds us that the human instinct to play can be harnessed for the greater good. With a stirring blend of energy, wisdom, and idealism, Jane McGonigal shows us how to start saving the world one game at a time.” —Carl Honoré, author of In Praise of Slowness and Under Pressure “Reality Is Broken is the most eye-opening book I read this year. With awe-inspiring ex pertise, clarity of thought, and engrossing writing style, Jane McGonigal cleanly exploded every misconception I’ve ever had about games and gaming. If you thought that games are for kids, that games are squandered time, or that games are dangerously isolating, addictive, unproductive, and escapist, you are in for a giant surprise!” —Sonja Lyubomirsky, Ph.D., professor of psychology at the University of California, Riverside, and author of The How of Happiness: A Scientific Approach to Getting the Life You Want “Reality Is Broken will both stimulate your brain and stir your soul. Once you read this remarkable book, you’ll never look at games—or yourself—quite the same way.” —Daniel H. Pink, author of Drive and A Whole New Mind “The path to becoming happier, improving your business, and saving the world might be one and the same: understanding how the world’s best games work. -

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why Is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving?

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving? A Thesis Submitted By Jacob Zvi for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Faculty of Health, Arts & Design, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne © Jacob Zvi 2019 Swinburne University of Technology All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. II Abstract In 2004, annual Australian viewership of Australian cinema, regularly averaging below 5%, reached an all-time low of 1.3%. Considering Australia ranks among the top nations in both screens and cinema attendance per capita, and that Australians’ biggest cultural consumption is screen products and multi-media equipment, suggests that Australians love cinema, but refrain from watching their own. Why? During its golden period, 1970-1988, Australian cinema was operating under combined private and government investment, and responsible for critical and commercial successes. However, over the past thirty years, 1988-2018, due to the detrimental role of government film agencies played in binding Australian cinema to government funding, Australian films are perceived as under-developed, low budget, and depressing. Out of hundreds of films produced, and investment of billions of dollars, only a dozen managed to recoup their budget. The thesis demonstrates how ‘Australian national cinema’ discourse helped funding bodies consolidate their power. Australian filmmaking is defined by three ongoing and unresolved frictions: one external and two internal. Friction I debates Australian cinema vs. Australian audience, rejecting Australian cinema’s output, resulting in Frictions II and III, which respectively debate two industry questions: what content is produced? arthouse vs. -

Negotiating the Non-Narrative, Aesthetic and Erotic in New Extreme Gore

NEGOTIATING THE NON-NARRATIVE, AESTHETIC AND EROTIC IN NEW EXTREME GORE. A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication, Culture, and Technology By Colva Weissenstein, B.A. Washington, DC April 18, 2011 Copyright 2011 by Colva Weissenstein All Rights Reserved ii NEGOTIATING THE NON-NARRATIVE, AESTHETIC AND EROTIC IN NEW EXTREME GORE. Colva O. Weissenstein, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Garrison LeMasters, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This thesis is about the economic and aesthetic elements of New Extreme Gore films produced in the 2000s. The thesis seeks to evaluate film in terms of its aesthetic project rather than a traditional reading of horror as a cathartic genre. The aesthetic project of these films manifests in terms of an erotic and visually constructed affective experience. It examines the films from a thick descriptive and scene analysis methodology in order to express the aesthetic over narrative elements of the films. The thesis is organized in terms of the economic location of the New Extreme Gore films in terms of the film industry at large. It then negotiates a move to define and analyze the aesthetic and stylistic elements of the images of bodily destruction and gore present in these productions. Finally, to consider the erotic manifestations of New Extreme Gore it explores the relationship between the real and the artificial in horror and hardcore pornography. New Extreme Gore operates in terms of a kind of aesthetic, gore-driven pornography. Further, the films in question are inherently tied to their economic circumstances as a result of the significant visual effects technology and the unstable financial success of hyper- violent films.