Japanese Traditional Miso and Koji Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,395,889 B1 Robison (45) Date of Patent: May 28, 2002

USOO6395889B1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,395,889 B1 Robison (45) Date of Patent: May 28, 2002 (54) NUCLEIC ACID MOLECULES ENCODING WO WO-98/56804 A1 * 12/1998 ........... CO7H/21/02 HUMAN PROTEASE HOMOLOGS WO WO-99/0785.0 A1 * 2/1999 ... C12N/15/12 WO WO-99/37660 A1 * 7/1999 ........... CO7H/21/04 (75) Inventor: fish E. Robison, Wilmington, MA OTHER PUBLICATIONS Vazquez, F., et al., 1999, “METH-1, a human ortholog of (73) Assignee: Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., ADAMTS-1, and METH-2 are members of a new family of Cambridge, MA (US) proteins with angio-inhibitory activity', The Journal of c: - 0 Biological Chemistry, vol. 274, No. 33, pp. 23349–23357.* (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this Descriptors of Protease Classes in Prosite and Pfam Data patent is extended or adjusted under 35 bases. U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. * cited by examiner (21) Appl. No.: 09/392, 184 Primary Examiner Ponnathapu Achutamurthy (22) Filed: Sep. 9, 1999 ASSistant Examiner William W. Moore (51) Int. Cl." C12N 15/57; C12N 15/12; (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Alston & Bird LLP C12N 9/64; C12N 15/79 (57) ABSTRACT (52) U.S. Cl. .................... 536/23.2; 536/23.5; 435/69.1; 435/252.3; 435/320.1 The invention relates to polynucleotides encoding newly (58) Field of Search ............................... 536,232,235. identified protease homologs. The invention also relates to 435/6, 226, 69.1, 252.3 the proteases. The invention further relates to methods using s s s/ - - -us the protease polypeptides and polynucleotides as a target for (56) References Cited diagnosis and treatment in protease-mediated disorders. -

Plant Protease Inhibitors: a Defense Strategy in Plants

Biotechnology and Molecular Biology Review Vol. 2 (3), pp. 068-085, August 2007 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/BMBR ISSN 1538-2273 © 2007 Academic Journals Standard Review Plant protease inhibitors: a defense strategy in plants Huma Habib and Khalid Majid Fazili* Department of Biotechnology, The University of Kashmir, P/O Naseembagh, Hazratbal, Srinagar -190006, Jammu and Kashmir, India. Accepted 7 July, 2007 Proteases, though essentially indispensable to the maintenance and survival of their host organisms, can be potentially damaging when overexpressed or present in higher concentrations, and their activities need to be correctly regulated. An important means of regulation involves modulation of their activities through interaction with substances, mostly proteins, called protease inhibitors. Some insects and many of the phytopathogenic microorganisms secrete extracellular enzymes and, in particular, enzymes causing proteolytic digestion of proteins, which play important roles in pathogenesis. Plants, however, have also developed mechanisms to fight these pathogenic organisms. One important line of defense that plants have to fight these pathogens is through various inhibitors that act against these proteolytic enzymes. These inhibitors are thus active in endogenous as well as exogenous defense systems. Protease inhibitors active against different mechanistic classes of proteases have been classified into different families on the basis of significant sequence similarities and structural relationships. Specific protease inhibitors are currently being overexpressed in certain transgenic plants to protect them against invaders. The current knowledge about plant protease inhibitors, their structure and their role in plant defense is briefly reviewed. Key words: Proteases, enzymes, protease inhibitors, serpins, cystatins, pathogens, defense. Table of content 1. -

Setagaya City Walking

Compilation of Ken PULS B walking Bo alanced die ko 5 recommended areacourses Introduction to this map efore you start dy shaping with a b t "Even though I am interested in getting healthy, I just can't seem to start." For people Before you walk Make wise food combination choices and who find themselves saying this, why not first try walking one of the courses you find enjoy your delicious food most interesting from "Sangen-jaya," "Shimo-Kitazawa," Todoroki," Bend and stretch knees Main dish "Chitose-Funabashi," and "Chitose-Karasuyama"? Meat, fish, eggs, Walking Map soy products, etc. 3 Setagaya/Kinuta- Side dishes Setagaya City Karasuyama Area Course vegetables, seaweed, 1 Kitazawa Area Course tubers, etc. Chitose-karasuyama Sta. ~ Sangen-jaya Sta. Stretch Stretch Higashi-matsubara Sta. ~ Shimo-kitazawa Sta. calves thighs Staples Soups Rice, bread, Soup, drinks, Kita-Karasuyama Karasuyama Sogo Shisho Keio Line Walking fashion style Shoe choice is key noodles desserts, etc. (District Administration Office) Koshu-Kaido highway Odakyu Minami- Ohara Odawara Line Kami- Hard to take off Kyuden Karasuyama Kitazawa Kitazawa Hanegi Kitazawa Sogo Shisho Cap * Loosen the laces Hachiman- Kasuya Matsubara (District Administration Office) around your toes. yama Sakura- Health insurance card The relationship between exercise and food can be compared to josui Aka- Daita Keio Tightly fasten Kami- zutsumi Soshigaya Inokashira the part nearest you. diet = the intake of energy and exercise and lifestyle = energy Line Funabashi Daizawa Chitosedai Umegaoka consumption. Maintain a good balance of food intake and exercise Kyodo T G e o Miya- m t p o City Hall l k Mishuku amounts (activity levels) which best suits you and maintain an e u Taishido Pedometer Adjust the fit of the width and nosaka j Soshigaya i Waka- Seijo bayashi Ikejiri height of your feet and appropriate weight. -

Serine Proteases with Altered Sensitivity to Activity-Modulating

(19) & (11) EP 2 045 321 A2 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 08.04.2009 Bulletin 2009/15 C12N 9/00 (2006.01) C12N 15/00 (2006.01) C12Q 1/37 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 09150549.5 (22) Date of filing: 26.05.2006 (84) Designated Contracting States: • Haupts, Ulrich AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR 51519 Odenthal (DE) HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC NL PL PT RO SE SI • Coco, Wayne SK TR 50737 Köln (DE) •Tebbe, Jan (30) Priority: 27.05.2005 EP 05104543 50733 Köln (DE) • Votsmeier, Christian (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in 50259 Pulheim (DE) accordance with Art. 76 EPC: • Scheidig, Andreas 06763303.2 / 1 883 696 50823 Köln (DE) (71) Applicant: Direvo Biotech AG (74) Representative: von Kreisler Selting Werner 50829 Köln (DE) Patentanwälte P.O. Box 10 22 41 (72) Inventors: 50462 Köln (DE) • Koltermann, André 82057 Icking (DE) Remarks: • Kettling, Ulrich This application was filed on 14-01-2009 as a 81477 München (DE) divisional application to the application mentioned under INID code 62. (54) Serine proteases with altered sensitivity to activity-modulating substances (57) The present invention provides variants of ser- screening of the library in the presence of one or several ine proteases of the S1 class with altered sensitivity to activity-modulating substances, selection of variants with one or more activity-modulating substances. A method altered sensitivity to one or several activity-modulating for the generation of such proteases is disclosed, com- substances and isolation of those polynucleotide se- prising the provision of a protease library encoding poly- quences that encode for the selected variants. -

JASON MARC GOLDSTEIN the Isolation, Characterization

JASON MARC GOLDSTEIN The Isolation, Characterization and Cloning of Three Novel Peptidases From Streptoccocus gordonii: Their Potential Roles in Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis (Under the Direction of JAMES TRAVIS) Streptococcus gordonii is generally considered a benign inhabitant of the oral microflora yet is a primary etiological agent in the development of subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE), an inflammatory state that propagates thrombus formation and tissue damage on the surface of heart valves. Colonization and adherence mechanisms have been identified, yet factors necessary to sustain growth remain unidentified. Strain FSS2 produced three extracellular aminopeptidase activities during growth in neutral pH- controlled batch cultures. The first included a serine-class dipeptidyl-aminopeptidase, an x-Pro DPP (Sg-xPDPP) found as an 85 kDa monomer by SDS-PAGE while appearing as a homodimer under native conditions. Kinetic studies indicated a unique and stringent x- Pro specificity comparable to the DPPIV/CD26 and lactococcal x-Pro DPP families. Isolation of the full-length gene uncovered a 759-amino acid polypeptide with a mass of 87,115 Da and theoretical pI of 5.6. Significant homology was found with PepX gene family members from Lactobacillus ssp. and Lactococcus ssp., and putative streptococcal x-Pro DPPs. The second activity was a putative serine-class arginine aminopeptidase (Sg- RAP) with some cysteine-class characteristics. It was found as a protein monomer of 70 kDa under denaturing conditions. Nested PCR cloning enabled the isolation of a 324 bp- long DNA fragment encoding the protein’s 108 amino acid N-terminus. Culture activity profiles and N-terminal sequence analysis indicated the release of this protein from the cell surface. -

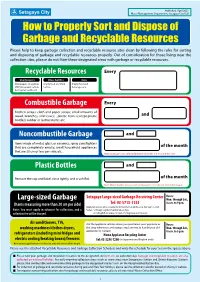

How to Properly Sort and Dispose of Garbage and Recyclable Resources

Published: April 2021 Setagaya City Waste Management Department, Setagaya City Hall How to Properly Sort and Dispose of Garbage and Recyclable Resources Please help to keep garbage collection and recyclable resource sites clean by following the rules for sorting and disposing of garbage and recyclable resources properly. Out of consideration for those living near the collection sites, please do not litter these designated areas with garbage or recyclable resources. Recyclable Resources Every Used papers Glass bottles Cans Newspapers, magazines Empty food and drink Empty food and Milk/juice paper cartons bottles beverage cans Corrugated cardboard Combustible Garbage Every Kitchen scraps; cloth and paper scraps; small amounts of wood, branches, and leaves; , plastic items (except plastic and bottles); rubber or leather items; etc. Noncombustible Garbage and Items made of metal, glass, or ceramics; spray cans/lighters that are completely empty; small household appliances of the month that are 30 cm or less per side; etc. Note: Garbage is not collected between the 29th and 31st of the month. Plastic Bottles and Remove the cap and label, rinse lightly, and crush flat. of the month Note: Plastic bottles are not collected between the 29th and 31st of the month. Setagaya Large-sized Garbage Receiving Center Hours: Large-sized Garbage Mon. through Sat., (Items measuring more than 30 cm per side) Tel: 03-5715-1133 8 a.m. to 9 p.m. Applications are also accepted via the Internet 24 hours a day year-round. Note: You must apply in advance for collection, and a Notes: 1. Except regular maintenance days. collection fee will be charged. -

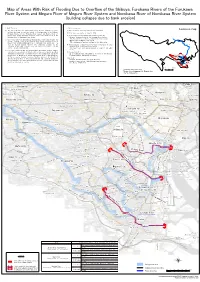

Map of Areas with Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Shibuya

Map of Areas With Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System (building collapse due to bank erosion) 1. About this map 2. Basic information Location map (1) This map shows the areas where there may be flooding powerful enough to (1) Map created by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government collapse buildings for sections subject to flood warnings of the Shibuya, (2) Risk areas designated on June 27, 2019 Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of Meguro River System and those subject to water-level notification of the (3) River subject to flood warnings covered by this map Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System. Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System (The flood warning section is shown in the table below.) (2) This river flood risk map shows estimated width of bank erosion along the Meguro River of Meguro River System Shibuya, Furukawa rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of (The flood warning section is shown in the table below.) Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System resulting from the maximum assumed rainfall. The simulation is based on the (4) Rivers subject to water-level notification covered by this map Sumida River situation of the river channels and flood control facilities as of the Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System time of the map's publication. (The water-level notification section is shown in the table below.) (3) This river flood risk map (building collapse due to bank erosion) roughly indicates the areas where buildings could collapse or be washed away when (5) Assumed rainfall the banks of the Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Up to 153mm per hour and 690mm in 24 hours in the Shibuya, Meguro River of Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River Furukawa, Meguro, Nomikawa Rivers basin Shibuya River,Furukawa River System are eroded. -

High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry-Based Approaches for the Detection and Quantification of Peptidase Activity in Plasma

molecules Article High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry-Based Approaches for the Detection and Quantification of Peptidase Activity in Plasma Elisa Maffioli 1,2 , Zhenze Jiang 3, Simona Nonnis 1,2 , Armando Negri 1,2, Valentina Romeo 1, Christopher B. Lietz 3, Vivian Hook 3,4, Giuseppe Ristagno 5, Giuseppe Baselli 6, Erik B. Kistler 7,8 , Federico Aletti 9, Anthony J. O’Donoghue 3,* and Gabriella Tedeschi 1,2,* 1 Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Milano, 20133 Milano, Italy; elisa.maffi[email protected] (E.M.); [email protected] (S.N.); [email protected] (A.N.); [email protected] (V.R.) 2 Centre for Nanostructured Materials and Interfaces (CIMAINA), University of Milano, 20133 Milano, Italy 3 Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA; [email protected] (Z.J.); [email protected] (C.B.L.); [email protected] (V.H.) 4 Department of Neurosciences, School of Medicine, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA 5 Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, University of Milan, 20133 Milan, Italy; [email protected] 6 Dipartimento di Elettronica, Informazione e Bioingegneria, Politecnico di Milano, 20133 Milan, Italy; [email protected] 7 Department of Anesthesiology & Critical Care, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA; [email protected] 8 Department of Anesthesiology & Critical Care, VA San Diego HealthCare System, San Diego, CA 92161, USA 9 Department of Bioengineering, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.J.O.); [email protected] (G.T.); Tel.: +1-8585345360 (A.J.O.); +39-02-50318127 (G.T.) Academic Editor: Paolo Iadarola Received: 28 July 2020; Accepted: 4 September 2020; Published: 6 September 2020 Abstract: Proteomic technologies have identified 234 peptidases in plasma but little quantitative information about the proteolytic activity has been uncovered. -

Loss of Protease Activity of ADAM15 Abolishes Protective Effects on Plaque Progression in Atherosclerosis

382 Letters to the Editor Loss of protease activity of ADAM15 abolishes protective effects on plaque progression in atherosclerosis Andreas Bültmann, Zhongmin Li, Silvia Wagner, Meinrad Gawaz, Martin Ungerer, Harald Langer, Andreas E. May ⁎⁎, Götz Münch ⁎ Corimmun, Fraunhofer Str. 17, D-82152 Martinsried, Germany Medizinische Klinik III, Eberhard-Karls Universität Tübingen, D-72076 Tübingen, Germany article info For the induction of atherosclerosis, rabbits were fed with Western Article history: type high cholesterol (0.25%) diet for 8 weeks and vascular gene Received 8 August 2011 transfer to the carotid artery was performed as previously described Accepted 13 August 2011 [7]. Available online 9 September 2011 Animals were sacrificed 4 weeks after the adenovirus delivery. Keywords: The left common carotid arteries, aorta and iliac arteries were Atherosclerosis macroscopically prepared for “en face” evaluation of plaque ADAM15 extension and stained with Sudan III. Serial 6-μm-thick cryosections Sheddase were cut and histological assessment of atherosclerosis after Metalloproteinase hematoxylin eosin (HE) and van Gieson (VG)-elastica staining and GFP expression were performed. Immunohistochemical analysis, with anti rabbit RAM 11 antibody (DAKO, Hamburg, Germany) was The A Disintegrin And Metallporteinases (ADAMs) contain a used for macrophages as previously described [12]. metalloprotease-like and a disintegrin-like domain. Currently 40 After vascular gene transfer into the carotid artery, GFP expression different types of ADAM proteins have been identified. ADAM15 is could be detected with AdGFP and also with Ad-ADAM15 and Ad- found in the myocardium [1,2], endothelial cells and in vascular ADAM15 prot neg, which both co-expressed GFP (Fig. 1). Relative atherosclerotic lesions [3]. -

Dipeptidyl Peptidase 4 Is a Functional Receptor for the Emerging Human Coronavirus-EMC

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature12005 Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC V. Stalin Raj1*, Huihui Mou2*, Saskia L. Smits1,3, Dick H. W. Dekkers4, Marcel A. Mu¨ller5, Ronald Dijkman6, Doreen Muth5, Jeroen A. A. Demmers4, Ali Zaki7, Ron A. M. Fouchier1, Volker Thiel6,8, Christian Drosten5, Peter J. M. Rottier2, Albert D. M. E. Osterhaus1, Berend Jan Bosch2 & Bart L. Haagmans1 Most human coronaviruses cause mild upper respiratory tract dis- antigen-related cell adhesion molecules (CEACAM)10 to enter cells, ease but may be associated with more severe pulmonary disease in whereas for several Alpha- and Betacoronaviruses, two peptidases immunocompromised individuals1. However, SARS coronavirus have been identified as receptors (aminopeptidase N (APN, CD13) caused severe lower respiratory disease with nearly 10% mortality for hCoV-229E and several animal coronaviruses11,12, and angiotensin and evidence of systemic spread2. Recently, another coronavirus (human coronavirus-Erasmus Medical Center (hCoV-EMC)) was a identified in patients with severe and sometimes lethal lower res- )] Vero –1 piratory tract infection3,4. Viral genome analysis revealed close 9 ml 8 5 50 relatedness to coronaviruses found in bats . Here we identify 7 dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4; also known as CD26) as a functional 6 5 receptor for hCoV-EMC. DPP4 specifically co-purified with the 4 receptor-binding S1 domain of the hCoV-EMC spike protein from 3 Relative cell number log[GE (TCID 0 20 40 lysates of susceptible Huh-7 cells. Antibodies directed against 0 101 102 103 104 DPP4 inhibited hCoV-EMC infection of primary human bronchial b )] COS-7 –1 epithelial cells and Huh-7 cells. -

Adachi-Ku Nerima-Ku Setagaya-Ku Suginami-Ku Itabashi-City Minato

2. 基本 的事 項等 Mapof Areas With Risk of Flooding Due to Ove rflowof (1) 作成(1) 主体 東 京 都 (2) 指(2) 定年 月日 令 和 元 年 5月23日 theShakujii Rive of r the Arakawa Rive System r (3) 告示番号(3) 東 京 都告示第55号 (4) 指(4) 定の 根 拠 法令 水 防法(昭和 24年法律 第193号)第14条第2項 (inundation duration) (5) 対象とな(5) る 水 位 周知河 川 ・荒川 水 系石神井 川 (実施 区間:下 表に示す通り) (6) 指(6) 定の 前提 とな る 降雨 石神井 川 流 域 の 1時間最 大雨量153mm 1. About this map 2. Basic information 24時間総雨量690mm Locationmap (1) Pursuant to the provisions of the Flood Control Act, this map shows the duration of inundation for the maximum assumed (1) Map created by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government 【問い合わせ先 】 rainfall for sections those subject to water-level notification of the Shakujii River of the Arakawa River System. (2) Map created on May 23, 2019 東 京 都建 設局 河 川 部防災課 03-5321-1111(代) (2) This river flood risk map shows the estimated duration of 50cm or deeper inundation that occurs due to overflow of the (3) Released as TMG announcement No.55 Shakujii River of the Arakawa River System resulting from the maximum assumed rainfall. The simulation is based on the situation of the river channels and flood control facilities as of the time of the map's publication. (4) Designation made based on Article 14, paragraph 2 of the Flood Control Act SumidaRive r (Act No. 193 of 1949) (3) Because the simulation does not take into account flooding of tributaries or flooding caused by rainfall greater than ShakujiiRive r the assumed level, by a storm surge, or by runoff of rainwater, the actual duration of inundation may differ from the (5) River subject to flood warnings covered by this map Shakujii River of the Arakawa River System estimates and inundation may also occur in areas not indicated on this map. -

And Exopeptidases in a Processing Enzyme System: Activation

Proc. Nail. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 85, pp. 5468-5472, August 1988 Biochemistry Relationship between endo- and exopeptidases in a processing enzyme system: Activation of an endoprotease by the aminopeptidase B-like activity in somatostatin-28 convertase (brain cortex/basic amino acid pairs/peptide substrates/protease inhibitors/prohormone maturation) SOPHIE GOMEZ, PABLO GLUSCHANKOF, AGNES LEPAGE, AND PAUL COHEN Groupe de Neurobiochimie Cellulaire et Moldculaire, Universitd Pierre et Marie Curie, Unitd Associde 554 au Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 96 boulevard Raspail, 75006 Paris, France Communicated by I. Robert Lehman, April 8, 1988 (receivedfor review December 15, 1987) ABSTRACT The somatostatin-28 convertase activity in- somatostatin-14 and the amino-terminal dodecapeptide so- volved in vitro in the processing of somatostatin-28 into the matostatin-28-(1-12) (16). neuropeptides somatostatin-28-(1-12) and somatostatin-14 is We have described an endoprotease that cleaves the composed of an endoprotease and a basic aminopeptidase. We peptide bond on the amino side ofthe Arg-Lys doublet in the report herein on the purification to apparent homogeneity of somatostatin-28 sequence (17, 18), releasing the somato- these two constituents and on their functional interrelationship. statin-28-(1-12) fragment and [Arg-2,Lys-1]somatostatin-14. In particular we observed that after various physicochemical The released [Arg-2,Lys-']somatostatin-14 is further proc- treatments, the 90-kDa endoprotease activity was recovered essed by an aminopeptidase B-like activity (18, 19) that is also both at this molecular mass and as a 45-kDa entity. Moreover, present in the preparation. We report herein the purification the production of [Arg2,LysJllsomatostatin-14 from somato- to apparent homogeneity ofthese two activities.