Corporate Social Irresponsibility: Humans Vs Artificial Intelligence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLONES, BONES and TWILIGHT ZONES: PROTECTING the DIGITAL PERSONA of the QUICK, the DEAD and the IMAGINARY by Josephj

CLONES, BONES AND TWILIGHT ZONES: PROTECTING THE DIGITAL PERSONA OF THE QUICK, THE DEAD AND THE IMAGINARY By JosephJ. Beard' ABSTRACT This article explores a developing technology-the creation of digi- tal replicas of individuals, both living and dead, as well as the creation of totally imaginary humans. The article examines the various laws, includ- ing copyright, sui generis, right of publicity and trademark, that may be employed to prevent the creation, duplication and exploitation of digital replicas of individuals as well as to prevent unauthorized alteration of ex- isting images of a person. With respect to totally imaginary digital hu- mans, the article addresses the issue of whether such virtual humans should be treated like real humans or simply as highly sophisticated forms of animated cartoon characters. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN TR O DU C T IO N ................................................................................................ 1166 II. CLONES: DIGITAL REPLICAS OF LIVING INDIVIDUALS ........................ 1171 A. Preventing the Unauthorized Creation or Duplication of a Digital Clone ...1171 1. PhysicalAppearance ............................................................................ 1172 a) The D irect A pproach ...................................................................... 1172 i) The T echnology ....................................................................... 1172 ii) Copyright ................................................................................. 1176 iii) Sui generis Protection -

Humana.Mente Complete Issue 26.Pdf

EDITORIAL MANAGER: DUCCIO MANETTI - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE Editorial EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: SILVANO ZIPOLI CAIANI - UNIVERSITY OF MILAN VICE DIRECTOR: MARCO FENICI - UNIVERSITY OF SIENA Board INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL BOARD JOHN BELL - UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO GIOVANNI BONIOLO - INSTITUTE OF MOLECULAR ONCOLOGY FOUNDATION MARIA LUISA DALLA CHIARA - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE DIMITRI D'ANDREA - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE BERNARDINO FANTINI - UNIVERSITÉ DE GENÈVE LUCIANO FLORIDI - UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD MASSIMO INGUSCIO - EUROPEAN LABORATORY FOR NON-LINEAR SPECTROSCOPY GEORGE LAKOFF - UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY PAOLO PARRINI - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE ALBERTO PERUZZI - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE JEAN PETITOT - CREA, CENTRE DE RECHERCHE EN ÉPISTÉMOLOGIE APPLIQUÉE CORRADO SINIGAGLIA - UNIVERSITY OF MILAN BAS C. VAN FRAASSEN - SAN FRANCISCO STATE UNIVERSITY CONSULTING EDITORS CARLO GABBANI - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE ROBERTA LANFREDINI - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE MARCO SALUCCI - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE ELENA ACUTI - UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE MATTEO BORRI - UNIVERSITÉ DE GENÈVE ROBERTO CIUNI - UNIVERSITY OF DELFT Editorial SCILLA BELLUCCI, LAURA BERITELLI, RICCARDO FURI, ALICE GIULIANI, STEFANO LICCIOLI, UMBERTO MAIONCHI Staff HUMANA.MENTE - QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Fiorella Battaglia, Antonio Carnevale Epistemological and Moral Problems with Human Enhancement III PAPERS Volker Gerhardt Technology as a Medium of Ethics and Culture 1 Nikil Mukerji, Julian Nida-Rümelin Towards a Moderate Stance on Human Enhancement 17 Christopher -

M.A. Maciver's Dissertation

The computational neuroethology of weakly electric fish body modeling, motion analysis, and sensory signal estimation R s R s C R s i C s 1 Z = + X prey + + s 1/ Rp 1/ Xp 1/ Zs −ρ ρ E ⋅r 1 p / w δφ(r) = fish a3 3 + ρ ρ r 1 2 p / w − t − t = 1/ v + + − 1/ v + vt vt−1e g(1 mt )(1 e ) nt − t = 1/ w wt wt−1e = − st H(vt wt ) = + ∆ ⋅ wt wt w st Malcolm Angus MacIver THE COMPUTATIONAL NEUROETHOLOGY OF WEAKLY ELECTRIC FISH: BODY MODELING, MOTION ANALYSIS, AND SENSORY SIGNAL ESTIMATION BY MALCOLM ANGUS MACIVER B.Sc., University of Toronto, 1991 M.A., University of Toronto, 1992 THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Neuroscience in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2001 Urbana, Illinois c Copyright by Malcolm Angus MacIver, 2001 ABSTRACT Animals actively influence the content and quality of sensory information they acquire through the positioning of peripheral sensory surfaces. Investigation of how the body and brain work together for sensory acquisition is hindered by 1) the limited number of techniques for tracking sensory surfaces, few of which provide data on the position of the entire body surface, and by 2) our inability to measure the thousands of sensory afferents stimulated during behav- ior. I present research on sensory acquisition in weakly electric fish of the genus Apteronotus, where I overcame the first barrier by developing a markerless tracking system and have de- ployed a computational approach toward overcoming the second barrier. -

CYBORGIZATION and VIRTUAL WORLDS: Portals to Altered Reality

Sample file CYBORGIZATION AND VIRTUAL WORLDS: A character’s body is the means by which she perceives Portals to Altered Reality and interacts with her environment. When a character ex- tends her body by grafting robotic components onto it – or Volume 02 in the replaces some of its key components with biosynthetic sub- Posthuman Cyberware Sourcebook series stitutes – it inevitably alters the way in which she experi- ences the world. Written and edited by: Matthew E. Gladden The nature of a character’s forays into virtual reality is just one part of her life that’s transformed by the process of Special thanks to cyborgization. After all, it’s easy to know when you enter All those who offered feedback regarding the research and ma- a virtual environment if the tools you’re using are a VR terials that eventually found their way into this volume, as well headset and haptic feedback gloves. If the virtual experi- as those whose work as game designers, gamers, scholars, and ence is too much for you, you can always just rip off the authors provided inspiration for this project, including: headset: the digital illusions instantly vanish, and you know that you’re back in the ‘real’ world. But what if the Magdalena Szczepocka Sven Dwulecki VR gear that you’re employing consists of cranial neural Bartosz Kłoda-Staniecko Mateusz Zimnoch implants that directly stimulate your brain to create artifi- Paweł Gąska Nicole Cunningham cial sensory experiences? Or what if you’re toting dual-pur- Krzysztof Maj Ted Snider pose artificial eyes and robotic prosthetic limbs that can ei- Ksenia Olkusz Ken Spencer ther supply you with authentic sense data from the external Michał Kłosiński Nathan Fouts environment or switch into iso mode, cut off all the sensa- tions from the real world, and pipe fabricated sense data into your brain? What signs could you look for to help you Copyright © 2017 Matthew E. -

A History of Laser Scanning, Part 2: the Later Phase of Industrial and Heritage Applications

A History of Laser Scanning, Part 2: The Later Phase of Industrial and Heritage Applications Adam P. Spring Abstract point clouds of 3D information thus generated (Takase et al. The second part of this article examines the transition of 2003). Software packages can be proprietary in nature—such as midrange terrestrial laser scanning (TLS)–from applied Leica Geosystems’ Cyclone, Riegl’s RiScan, Trimble’s Real- research to applied markets. It looks at the crossover of Works, Zoller + Fröhlich’s LaserControl, and Autodesk’s ReCap technologies; their connection to broader developments in (“Leica Cyclone” 2020; “ReCap” n.d.; “RiScan Pro 2.0” n.d.; computing and microelectronics; and changes made based “Trimble RealWorks” n.d.; “Z+F LaserControl” n.d.)—or open on application. The shift from initial uses in on-board guid- source, like CloudCompare (Girardeau-Montaut n.d.). There are ance systems and terrain mapping to tripod-based survey for even plug-ins for preexisting computer-aided design (CAD) soft- as-built documentation is a main focus. Origins of terms like ware packages. For example, CloudWorx enables AutoCAD users digital twin are identified and, for the first time, the earliest to work with point-cloud information (“Leica CloudWorx” examples of cultural heritage (CH) based midrange TLS scans 2020; “Leica Cyclone” 2020). Like many services and solutions, are shown and explained. Part two of this history of laser AutoCAD predates the incorporation of 3D point clouds into scanning is a comprehensive analysis upto the year 2020. design-based workflows (Clayton 2005). Enabling the user base of pre-existing software to work with point-cloud data in this way–in packages they are already educated in–is a gateway to Introduction increased adoption of midrange TLS. -

Posthuman Cyberware

POSTHUMAN CYBERWARE: The idea of an implantable memory chip that lets you instantly Blurring the Boundaries of Mind, download new skills sounds great, but could such a device actually Body, and Computer work? Given the different formats that their brains use for storing semantic content, would you need, say, one version of the implant for English speakers and another for Japanese speakers? And which Volume 01 in the of your cognitive functions could a hacker access by compromising Posthuman Cyberware Sourcebook series such a device? Could a human mind figure out how to operate a cy- borg body that has wheels or dozens of robotic tentacles? If relatively small changes in brain temperature can cause behavioral impacts (or Written and edited by: Matthew E. Gladden even brain damage), is it really advisable to implant a heat-spewing miniaturized supercomputer in someone’s cranium? If you’ve ever Special thanks to thought about any of these questions when designing or running an All those who offered feedback regarding the research and ma- adventure, then this is the book – and series – for you. terials that eventually found their way into this volume, as well There are many remarkable and pioneering games (like Cyber- as those whose work as game designers, gamers, scholars, and punk 2020, Shadowrun, Cyberspace, GURPS Cyberpunk, Kazei-5, Trans- authors provided inspiration for this project, including: human Space, Ex Machina, Eclipse Phase, and Interface Zero 2.0) that in- Magdalena Szczepocka Sven Dwulecki corporate futuristic neuroprosthetic hardware and cybernetic aug- mentation as significant elements of their game-worlds, character Bartosz Kłoda-Staniecko Mateusz Zimnoch design, and adventure plots. -

Kazei 5 Preview

Part One o Introduction & Campaign Basics 5 Campaign Basics At one point the Kazei 5 is laid out as twenty-first century was “I firmly believe that before many centuries more, sci- follows: NOTE FROM predicted to be a tech- ence will be the master of man. The engines he will have Part 1: Intro- THE AUTHOR nological paradise, with invented will be beyond his strength to control. Some day duction And Cam- Some of you may flying cars, vacations on science shall have the existence of mankind in its power, paign Basics — The recall (and even the moon, and robotic and the human race shall commit suicide by blowing up section you are reading own) the earlier, servants performing most the world.” right now, which includes household chores. Food Hero Games edition — Henry Adams, 1862 a brief discussion of the of Kazei 5 and may would come in small pills, cyberpunk genre, as well crippling diseases would wonder what this as anime and manga, and how the two relate to volume will offer be a thing of the past, automation would mean more Kazei 5. leisure time for everyone, and atomic power would hold that the previous Part 2: Cybertech, Cyberspace, and Cy- the answers to all of man’s energy needs. book didn’t. My berarmor: The Animepunk Sourcebook intent when writing If only it were so simple. — This section is broken into a series of chapters, Kazei 5 Second Edi- The world of 2030 is a far cry from the one imagined each of which examines a different facet of the tion was to update during the highly optimistic 1950s. -

Transhumanism

T ranshumanism - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=T ranshum... Transhumanism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia See also: Outline of transhumanism Transhumanism is an international Part of Ideology series on intellectual and cultural movement supporting Transhumanism the use of science and technology to improve human mental and physical characteristics Ideologies and capacities. The movement regards aspects Abolitionism of the human condition, such as disability, Democratic transhumanism suffering, disease, aging, and involuntary Extropianism death as unnecessary and undesirable. Immortalism Transhumanists look to biotechnologies and Libertarian transhumanism other emerging technologies for these Postgenderism purposes. Dangers, as well as benefits, are Singularitarianism also of concern to the transhumanist Technogaianism [1] movement. Related articles The term "transhumanism" is symbolized by Transhumanism in fiction H+ or h+ and is often used as a synonym for Transhumanist art "human enhancement".[2] Although the first known use of the term dates from 1957, the Organizations contemporary meaning is a product of the 1980s when futurists in the United States Applied Foresight Network Alcor Life Extension Foundation began to organize what has since grown into American Cryonics Society the transhumanist movement. Transhumanist Cryonics Institute thinkers predict that human beings may Foresight Institute eventually be able to transform themselves Humanity+ into beings with such greatly expanded Immortality Institute abilities as to merit the label "posthuman".[1] Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence Transhumanism is therefore sometimes Transhumanism Portal · referred to as "posthumanism" or a form of transformational activism influenced by posthumanist ideals.[3] The transhumanist vision of a transformed future humanity has attracted many supporters and detractors from a wide range of perspectives. -

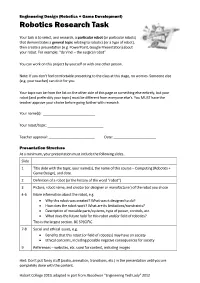

Robotics Research Task

Engineering Design (Robotics + Game Development) Robotics Research Task Your task is to select, and research, a particular robot (or particular robots) that demonstrates a general topic relating to robotics (or a type of robot), then create a presentation (e.g. PowerPoint, Google Presentation) about your robot. For example: “da Vinci – the surgical robot” You can work on this project by yourself or with one other person. Note: If you don’t feel comfortable presenting to the class at this stage, no worries. Someone else (e.g. your teacher) can do it for you. Your topic can be from the list on the other side of this page or something else entirely, but your robot (and preferably your topic) must be different from everyone else’s. You MUST have the teacher approve your choice before going further with research. Your name(s): ___________________________ Your robot/topic: _____________________________ Teacher approval: ________________________ Date: ______________________ Presentation Structure At a minimum, your presentation must include the following slides… Slide 1 Title slide with the topic, your name(s), the name of this course – Computing (Robotics + Game Design), and date. 2 Definition of a robot (or the history of the word “robot”) 3 Picture, robot name, and creator (or designer or manufacturer) of the robot you chose 4-6 More information about the robot, e.g. • Why this robot was created? What was it designed to do? • How does the robot work? What are its limitations/constraints? • Description of movable parts/systems, type of power, controls, etc. • What does the future hold for this robot and/or field of robotics? This is the largest section. -

The Videoludic Cyborg : Queer/Feminist Reappropriations and Hybridity

The Philosophy of Computer Games Conference, Copenhagen 2018 The Videoludic Cyborg : Queer/Feminist Reappropriations and Hybridity Roxanne Chartrand and Pascale Thériault Introduction Video game culture is heavily tainted with militarized masculinity and has therefore often been described as toxic (Consalvo 2012). The state of this world, which is vastly harmful to women, people of color and marginalized people, could be explained by the military-industrial origins of video games. Indeed, "interactive game designers and marketers, starting from an intensely militarized institutional incubator, forged a deep connexion with their youthful core male gaming aficionados, but failed or ignored other audiences and gaming options" (Kline et al. 2003: 265). What Kline et al. called militarized masculinity is in fact a hegemonic discourse, or a dominant theme, of a "shared semiotic nexus revolving around issues of war, conquest and combat", or "militarist subtexts of conquest and imperialism" (Kline et al. 2003: 255), which ultimately resulted in evacuating marginalized people and diversity in video games to the benefit of similar content, primarily addressing a white cishet men audience. There are many incidents of harassment, violence, racism, sexism in video game content, and in many video game communities. As Consalvo said, Each event taken in isolation is troubling enough, but chaining them together into a timeline demonstrates how the individual links are not actually isolated incidents at all but illustrate a pattern of a misogynistic gamer culture and patriarchal privilege attempting to (re)assert its position. (Consalvo 2012) However, there is an increasing feminist and queer resistance in both video game creation and gaming practices. -

Handbook of Robotics Chapter 22

Handbook of Robotics Chapter 22 - Range Sensors Robert B. Fisher Kurt Konolige School of Informatics Artificial Intelligence Center University of Edinburgh SRI International [email protected] [email protected] June 26, 2008 Contents 22.1 Range sensing basics . ......... 1 22.1.1 Rangeimagesandpointsets . .......... 1 22.1.2 Stereovision .................................... ......... 2 22.1.3 Laser-based Range Sensors . ....... 7 22.1.4 TimeofFlightRangeSensors. ........... 7 22.1.5 Modulation Range Sensors . ........ 8 22.1.6 Triangulation Range Sensors . .......... 9 22.1.7 ExampleSensors ................................... ........ 9 22.2Registration .................................... ............. 10 22.2.1 3D Feature Representations . ......... 10 22.2.2 3DFeatureExtraction. ........... 12 22.2.3 Model Matching and Multiple-View Registration . .......... 13 22.2.4 Maximum Likelihood Registration . ............. 15 22.2.5 Multiple Scan Registration . ........... 15 22.2.6 Relative Pose Estimation . .............. 15 22.2.7 3DApplications ................................... ........ 16 22.3 Navigation and Terrain Classification . ................. 17 22.3.1 Indoor Reconstruction . ........ 17 22.3.2 UrbanNavigation ............................... ........... 18 22.3.3 RoughTerrain ................................... ......... 19 22.4 Conclusions and Further Reading . ........ 20 i CONTENTS 1 Range sensors are devices that capture the 3D struc- ture of the world from the viewpoint of the sensor, usu- ally measuring the depth to the nearest surfaces. These measurements could be at a single point, across a scan- ning plane, or a full image with depth measurements at every point. The benefits of this range data is that a robot can be relatively certain where the real world is, relative to the sensor, thus allowing the robot to more reliably find navigable routes, avoid obstacles, grasp ob- jects, act on industrial parts, etc. -

A Survey of Teleceptive Sensing for Wearable Assistive Robotic Devices

sensors Review A Survey of Teleceptive Sensing for Wearable Assistive Robotic Devices Nili E. Krausz 1,2,* and Levi J. Hargrove 1,2,3 1 Neural Engineering for Prosthetics and Orthotics Lab, Center of Bionic Medicine, Shirley Ryan AbilityLab (Formerly Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago), Chicago, IL 60611, USA; [email protected] 2 Biomedical Engineering Department, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA 3 Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Department, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-312-238-1562 Received: 16 September 2019; Accepted: 21 November 2019; Published: 28 November 2019 Abstract: Teleception is defined as sensing that occurs remotely, with no physical contact with the object being sensed. To emulate innate control systems of the human body, a control system for a semi- or fully autonomous assistive device not only requires feedforward models of desired movement, but also the environmental or contextual awareness that could be provided by teleception. Several recent publications present teleception modalities integrated into control systems and provide preliminary results, for example, for performing hand grasp prediction or endpoint control of an arm assistive device; and gait segmentation, forward prediction of desired locomotion mode, and activity-specific control of a prosthetic leg or exoskeleton. Collectively, several different approaches to incorporating teleception have been used, including sensor fusion, geometric segmentation, and machine learning. In this paper, we summarize the recent and ongoing published work in this promising new area of research. Keywords: assistive robotics; rehabilitation robotics; teleceptive sensing; environment; computer vision; depth sensing; prostheses; exoskeletons 1. Introduction Over the last few decades, the field of physical medicine and rehabilitation has seen a proliferation of wearable robotic devices designed to improve mobility, function, and quality of life for individuals with physical impairments.