AQA Poetry Anthology Power and Conflict Poem Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Elements of Poet :Y

CHAPTER 3 The Elements of Poet :y A Poetry Review Types of Poems 1, Lyric: subjective, reflective poetry with regular rhyme scheme and meter which reveals the poet’s thoughts and feelings to create a single, unique impres- sion. Matthew Arnold, "Dover Beach" William Blake, "The Lamb," "The Tiger" Emily Dickinson, "Because I Could Not Stop for Death" Langston Hughes, "Dream Deferred" Andrew Marvell, "To His Coy Mistress" Walt Whitman, "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking" 2. Narrative: nondramatic, objective verse with regular rhyme scheme and meter which relates a story or narrative. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, "Kubla Khan" T. S. Eliot, "Journey of the Magi" Gerard Manley Hopkins, "The Wreck of the Deutschland" Alfred, Lord Tennyson, "Ulysses" 3. Sonnet: a rigid 14-line verse form, with variable structure and rhyme scheme according to type: a. Shakespearean (English)--three quatrains and concluding couplet in iambic pentameter, rhyming abab cdcd efe___~f gg or abba cddc effe gg. The Spenserian sonnet is a specialized form with linking rhyme abab bcbc cdcd ee. R-~bert Lowell, "Salem" William Shakespeare, "Shall I Compare Thee?" b. Italian (Petrarchan)--an octave and sestet, between which a break in thought occurs. The traditional rhyme scheme is abba abba cde cde (or, in the sestet, any variation of c, d, e). Elizabeth Barrett Browning, "How Do I Love Thee?" John Milton, "On His Blindness" John Donne, "Death, Be Not Proud" 4. Ode: elaborate lyric verse which deals seriously with a dignified theme. John Keats, "Ode on a Grecian Urn" Percy Bysshe Shelley, "Ode to the West Wind" William Wordsworth, "Ode: Intimations of Immortality" Blank Verse: unrhymed lines of iambic pentameter. -

Gcse English Literature (8702)

GCSE ENGLISH LITERATURE (8702) Past and present: poetry anthology For exams from 2017 Version 1.0 June 2015 AQA_EngLit_GCSE_v08.indd 1 31/07/2015 22:14 AQA GCSE English Literature Past and present: poetry anthology All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing on any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the publisher, except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of the licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Notice to teachers: It is illegal to reproduce any part of this work in material form (including photocopying and electronic storage) except under the following circumstances: i) where you are abiding by a licence granted to your school or institution by the Copyright Licensing Agency; ii) where no such licence exists, or where you wish to exceed the terms of a licence, and you have gained the written permission of The Publishers Licensing Society; iii) where you are allowed to reproduce without permission under the provisions of Chapter 3 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Photo permissions 5 kieferpix / Getty Images, 6 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 8 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 9 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 11 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 12 Photos.com/Thinkstock, 13 Stuart Clarke/REX, 16 culture-images/Lebrecht, 16,© Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy, 17 Topfoto.co.uk, 18 Schiffer-Fuchs/ullstein -

Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning Was a Romantic Poet in Great Effect When Disclosing a Macabre Or Every Sense of the Word

THE GREAT Robert POETS Browning POETRY Read by David Timson and Patience Tomlinson NA192212D 1 How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix 3:49 2 Life in a Love 1:11 3 A Light Woman 3:42 4 The Statue and the Bust 15:16 5 My Last Duchess 3:53 6 The Confessional 4:59 7 A Grammarian’s Funeral 8:09 8 The Pied Piper of Hamelin 7:24 9 ‘You should have heard the Hamelin people…’ 8:22 10 The Lost Leader 2:24 11 Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister 3:55 12 The Laboratory 3:40 13 Porphyria’s Lover 3:47 14 Evelyn Hope 3:49 15 Home Thoughts from Abroad 1:19 16 Pippa’s Song 0:32 Total time: 76:20 = David Timson = Patience Tomlinson 2 Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning was a romantic poet in great effect when disclosing a macabre or every sense of the word. He was an ardent evil narrative, as in The Laboratory, or The lover who wooed the poet Elizabeth Confessional or Porphyria’s Lover. Barrett despite fierce opposition from Sometimes Browning uses this matter- her tyrannical father, while as a poet – of-fact approach to reduce a momentous inheriting the mantle of Wordsworth, occasion to the colloquial – in The Keats and Shelley – he sought to show, Grammarian’s Funeral, for instance, in in the Romantic tradition, man’s struggle which a scholar has spent his life pursuing with his own nature and the will of God. knowledge at the expense of actually But Browning was no mere imitator of enjoying life itself. -

My Last Duchess Porphyria's Lover Robert Browning 1812–1889

The Influence of Romanticism My Last Duchess RL 1 Cite strong and thorough Porphyria’s Lover textual evidence to support inferences drawn from the Poetry by Robert Browning text. RL 5 Analyze how an author’s choices concerning how to structure specific parts KEYWORD: HML12-944A of a text contribute to its overall VIDEO TRAILER structure and meaning as well as its aesthetic impact. RL 10 Read and comprehend literature, Meet the Author including poems. SL 1 Initiate and participate effectively in a range of collaborative discussions. Robert Browning 1812–1889 “A minute’s success,” remarked the poet character in an emotionally charged situation. Robert Browning, “pays for the failure of While critics attacked his early dramatic years.” Browning spoke from experience: poems, finding them difficult to understand, did you know? for years, critics either ignored or belittled Browning did not allow the reviews to keep his poetry. Then, when he was nearly 60, him from continuing to develop this form. Robert Browning . he became an object of near-worship. • became an ardent Secret Love In 1845, Browning met the admirer of Percy Bysshe Precocious Child An exceptionally bright poet Elizabeth Barrett and began a famous Shelley at age 12. child, Browning learned to read and write romance that has been memorialized in both • achieved fluency in by the time he was 5 and composed his film and literature. Against the wishes of Latin, Greek, Italian, and first, unpublished volume of poetry at Barrett’s overbearing father, the two poets French by age 14. 12. At the age of 21 he published his first married in secret in 1846 and eloped to • wrote the children’s book, Pauline (1833), to negative reviews. -

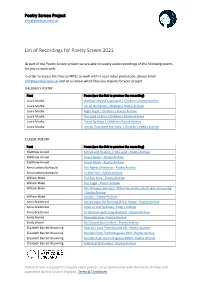

List of Recordings for Poetry Screen 2021

Poetry Screen Project [email protected] List of Recordings for Poetry Screen 2021 As part of the Poetry Screen project we are able to supply audio recordings of the following poems for you to work with. In order to access this files as MP3s to work with in your video production, please email [email protected] and let us know which files you require for your project. CHILDREN’S POETRY Poet Poem (use the link to preview the recording) Laura Mucha Wanted: Wizard's Assistant | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha I'm an Orchestra | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha Night Flight | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha The Land of Blue | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha Travel By Book | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha Words That Make Me Smile | Children's Poetry Archive CLASSIC POETRY Poet Poem (use the link to preview the recording) Matthew Arnold Sohrab and Rustum, ll. 857–end - Poetry Archive Matthew Arnold Dover Beach - Poetry Archive Matthew Arnold Dover Beach - Poetry Archive Anna Laetitia Barbauld The Rights of Woman - Poetry Archive Anna Laetitia Barbauld To the Poor - Poetry Archive William Blake The Sick Rose - Poetry Archive William Blake The Tyger - Poetry Archive William Blake The Chimney Sweeper: 'When my mother died I was very young' - Poetry Archive William Blake London - Poetry Archive Anne Bradstreet Verses Upon the Burning of Our House - Poetry Archive Anne Bradstreet Upon a Fit of Sickness - Poetry Archive Anne Bradstreet To My Dear and Living Husband - Poetry Archive Emily Bronté Remembrance - Poetry Archive Emily Bronté No Coward Soul Is Mine - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning How do I Love Thee (Sonnet 43) - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning Sonnets From The Portuguese XXIV - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning Sonnets from the Portuguese XXXVI - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning A Musical Instrument - Poetry Archive Poetry Screen is a project to inspire video poetry, run in partnership with the Poetry Archive and supported by Arts Council England. -

Ad Alta: the Birmingham Journal of Literature Volume Ix, 2017

Ad Alta: The Birmingham Journal of Literature Volume IX, 2017 AD ALTA: THE BIRMINGHAM JOURNAL OF LITERATURE VOLUME IX 2017 Cover image taken from ‘Axiom’ by WILLIAM BATEMAN Printed by Central Print, The University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK This issue is available online at: www.birmingham.ac.uk/adalta Ad Alta: the Birmingham Journal of Literature (Print) ISSN 2517-6951 Ad Alta: the Birmingham Journal of Literature (Online) ISSN 2517-696X © Ad Alta: the Birmingham Journal of Literature Questions and Submissions: Joshua Allsop and Jessica Pirie ([email protected]) GENERAL EDITORS Joshua Allsop & Jessica Pirie EDITORIAL BOARD Tom White REVIEW PANEL Emily Buffey Maryam Asiad Ruth Caddick POETRY AND ARTS EDITORS Hannah Comer Katherine Hughes Polly Duxfield Slava Rudin Brianna Grantham Charles Green NOTES EDITOR Christian Kusi-Obodum Yasmine Baker Paula Lameau James McCrink BOOK REVIEWS EDITOR Aurora Faye Martinez Geoff Mills Antonia Wimbush PROOFS EDITOR Jack Queenan Ad Alta: the Birmingham Journal of Literature wishes to acknowledge the hard work and generosity of a number of individuals, without whom this journal would never have made its way into your hands, or onto your computer screen. First, our editorial board Tom White and Emily Buffey should be thanked. Tom White, with tireless patience, was always available with invaluable advice and support throughout the entire process. Emily Buffey provided excellent feedback and commentary, sometimes at very short notice. Will Cooper of Central Print should also be thanked, without whose experience and expertise the publication of this journal would not have been possible. Also, our contributors, who dedicated so much precious time to writing and redrafting their submissions, and the section editors who guided and worked with them through that process. -

Gcse English and English Literature

GCSE ENGLISH AND ENGLISH LITERATURE INFORMATION AND PERSONAL PROFILE FOR STUDENTS AT ASHTON COMMUNITY SCIENCE COLLEGE NAME: ………………………………………….. TEACHER: ……………………………………. 1 THE COURSE(S) You will be following the AQA, Specification A syllabus for English . As an additional GCSE, many of you will be following the AQA, Specification A syllabus for English Literature . (www.aqa.org.uk) There are two methods of assessment within each course: 1. Coursework 2. Examination The following tables give you a breakdown of the elements that need to be studied and the work that needs to be completed in each area. The percentage weighting of each element in relation to your overall grade is also included: Coursework Written If you are entered for English and English Literature you will complete five written assignments. If you are entered for English only you will complete four written assignments: ASSIGNMENT EXAMPLE TASKS % OF OVERALL GCSE Original Writing A short story or an 5 % of the English GCSE (Writing assessment for autobiographical piece of English only) writing. Media A close analysis of an 5% of the English GCSE (Writing assessment for advertising campaign or of the English only) marketing for a film. Shakespeare A close analysis of the impact 5% of the English GCSE plus (Reading assessment for created by the first 95 lines in 10% of the English Literature English and English Lit.) Romeo and Juliet. GCSE Pre-Twentieth Century Prose A comparison between two 5% of the English GCSE plus Study chapters in Great Expectations 10% of the English Literature (Reading assessment for by Charles Dickens. GCSE English and English Lit.) Twentieth Century Play A close analysis of the role 10% of the English Literature (Assessment for English played by the narrator in Blood GCSE Literature only) Brothers by Willy Russell Spoken 2 In addition to written coursework there is also a spoken coursework element for English GCSE. -

Poetry – Year 8

Poetry – Year 8 % I can … Prove it! Students are beginning to explore: 1) What 3 things does Simon Armitage want us to realise about the narrator in Hitcher? You must explore how the tone and rhythm of the language reveal his personality. Write a 5 paragraph How rhythm can create tone essay. You should aim to include the words: mundane, familiar, un-poetic, contrasting, emotionless, nouns, cliché, turning point and stress. How an awareness of context develops a deeper exploration 2) What 3 key ideas about the theme of love does Shakespeare develop in Sonnet 130? You must of the poem. explore how the context of traditional love poetry and the format of the Sonnet can help you to explain Shakepseare’s motivations. Write a 5 paragraph essay. You should aim to include the 80%+ words: form, volta, stereotype, superficial, imagery, extended metaphor, 1590s, Elizabethean ideas of beauty, turning point, humour, truth, couplet & climax. 3) Out of the Blue – Choose 1-3 sections from Out of the Blue and explore how Simon Armitage uses techniques to reveal his thoughts and feelings about 9/11. What is the most important idea he wants readers to understand? Which line do you consider most powerful or effective and why? How does the form of the poem represent the title “out of the blue”? Students are beginning to explore: 1) How does the narrator speak? Bitterly, violently, confidently or in a fragile way. Does it depend? Explore how Duffy uses other poetic techniques to create Havisham’s tone of voice. Write a 5 How Extended Metaphors can paragraph essay. -

Theodora Michaeliodu Laura Pence Jonathan Tweedy John Walsh

Look, the world tempts our eye, And we would know it all! Setting is a basic characteristic of literature. Novels, short stories, classical Greece and medieval Europe and the literary traditions the temporal and spatial settings of individual literary works, one can dramas, film, and much poetry—especially narrative poetry—typically inspired by those periods. Major Victorian poets, including Tennyson, map and visualize the distribution of literary settings across historical We map the starry sky, have an identifiable setting in both time and space. Victorian poet the Brownings, Arnold, Rossetti, and Swinburne, provide a rich variety periods and geographic space; compare these data to other information, We mine this earthen ball, Matthew Arnold’s “Empedocles on Etna,” for instance, is set in Greek of representations of classical and medieval worlds. But what does the such as year of publication or composition; and visualize networks of We measure the sea-tides, we number the sea-sands; Sicily in the fifth century B.C. “Empedocles” was published in 1852. quantifiable literary data reveal about these phenomena? Of the total authors and works sharing common settings. The data set is a growing Swinburne’s Tristram of Lyonesse (1882) is set in Ireland, Cornwall, number of published works or lines of verse from any given period, collection of work titles, dates, date ranges, and geographic identifiers We scrutinise the dates and Brittany, but in an uncertain legendary medieval chronology. or among a defined set of authors or texts, how many texts have and coordinates. Challenges include settings of imprecise, legendary, Of long-past human things, In the absence of a narrative setting, many poems are situated classical, medieval, biblical, or contemporary settings? How many texts and fictional time and place. -

AFRICAN POETRY, VERNACULAR: ORAL. Ver• Tion to the Multiplicity of Local Classifications

A AFRICAN POETRY, VERNACULAR: ORAL. Ver tion to the multiplicity of local classifications . nacular poetry in Africa is mostly oral, and A basic distinction must be made between the greater part is still unrecorded. The con ritual and nonritual forms ; by far the most ventions of oral v.p. belong to the whole per important are the ritual forms associated, either formance and its occasion, and are therefore in origin or in present reality, with formal not exclusively literary. Internal classifications customary rites and activities. Modern public within the society have no referellce to the occasions may include traditional ritual forms Western categories of prose and poetry, and suitably adapted. Nonritual forms, of course, Afr. definitions of "literary" do not necessarily belong to informal occasions. In either general coincide with those of Eng .-Am. culture. For category the creative role of the performer(s) instance, Afr. proverbs and riddles are major, is important, for even within customary rites not minor, literary forms for which the term the evaluation is of the contemporary per "poetry," if it is applied, need not relate only formance. Ritual forms include panegyric and to the forms with rhyme. The evaluation even lyric, whereas nonritual forms include lyric of these identifiable genres can be made only and, possibly, narrative. by a complete understanding of the signifi Panegyric is one of the most developed and cance of any given member (e.g., a particular elaborate poetic genres in Africa. Its specialized praise song) of a genre (e.g., praise poetry) form is best exemplified in the court poetry of within the society at the time of utterance. -

Barbarian Masquerade a Reading of the Poetry of Tony Harrison And

1 Barbarian Masquerade A Reading of the Poetry of Tony Harrison and Simon Armitage Christian James Taylor Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of English August 2015 2 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation fro m the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement The right of Christian James Taylor to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. © 2015 The University of Leeds and Christian James Taylor 3 Acknowledgements The author hereby acknowledges the support and guidance of Dr Fiona Becket and Professor John Whale, without whose candour, humour and patience this thesis would not have been possible. This thesis is d edicat ed to my wife, Emma Louise, and to my child ren, James Byron and Amy Sophia . Additional thanks for a lifetime of love and encouragement go to my mother, Muriel – ‘ never indifferent ’. 4 Abstract This thesis investigates Simon Armitage ’ s claim that his poetry inherits from Tony Harrison ’ s work an interest in the politics o f form and language, and argues that both poets , although rarely compared, produce work which is conceptually and ideologically interrelated : principally by their adoption of a n ‘ un - poetic ’ , deli berately antagonistic language which is used to invade historically validated and culturally prestigious lyric forms as part of a critique of canons of taste and normative concepts of poetic register which I call barbarian masquerade . -

Chapter 3: EDWARD KAMAU BRATHWAITE: VISHWAKARMA ARRIVES

Chapter 3: EDWARD KAMAU BRATHWAITE: VISHWAKARMA ARRIVES 3 . 1 Introduct ion Edward Kamau Brathwaite is an unusual combination: he is a historian and poet. He is perhaps one of the most celebrated and one of the most discussed poets from the Caribbean Islands. Brathwaite is a classic example of an artist embodying the "homecoming' vision in his creative work. His 'journey home' has not been an easy one. Indeed it has been a long, tortuous journey at both physical and psychological levels, full of anguish which he underwent as much for himself as for his people. Brathwaite's development shows a familiar pattern: there is at first an awareness of carrying a stigmatized identity, followed by an attempt to erase it by running away from it. Then comes the awareness that the loss of self and a viable identity cannot be made up by running away from one's predicament and setting up a camp elsewhere to live in a sort of make- believe world. The dark night of the soul forces him to undertake a search to fathom his past. That is where the historian in Brathwaite takes over and transports him to Africa from where his people (not just ancestors as the term in such contexts usually implies but his felloM black men also) come. He fathoms the history of Africa before and after "the middle passage'. He is almost driven to despair when he realizes that Africa of today cannot give him an access to the "umbilical cord' of the black man tortured through slavery, but out of this very bleak realisation 101 Brathwaite creates a new world' for himself and roots himself there.