Barbarian Masquerade a Reading of the Poetry of Tony Harrison And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carol Ann Duffy

NCTE Verse - Carol Ann Duffy mail.google.com/mail/u/1 Poet of the Day: Carol Ann Duffy 1/5 Carol Ann Duffy, born in 1955, became the first female poet laureate of Britain in 2009. She often explores the perspectives of the voiceless women of history, mythology, and fairy tales as well as those on the fringes of society in her dramatic monologues. Duffy is most well-known for her collections Standing Female Nude (1985) and The World’s Wife (1999). She has also written plays and poetry for children. CC image “Carol Ann Duffy 8 Nov 2013 5” courtesy of Steel Wool on Flickr under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license. This poet belongs in our classrooms because… she explores the voices of those who have traditionally been silenced. Her poetry uses humor and emotion with simple language that hits us in the gut with its truth. It’s poetry that students can understand quickly but can also explore at length, uncovering its layers and relating to the speakers and their experiences. A Poem by Carol Ann Duffy Warming Her Pearls for Judith Radstone Next to my own skin, her pearls. My mistress bids me wear them, warm them, until evening when I'll brush her hair. At six, I place them round her cool, white throat. All day I think of her, 2/5 resting in the Yellow Room, contemplating silk or taffeta, which gown tonight? She fans herself whilst I work willingly, my slow heat entering each pearl. Slack on my neck, her rope. -

Full Bibliography (PDF)

SOMHAIRLE MACGILL-EAIN BIBLIOGRAPHY POETICAL WORKS 1940 MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. 17 Poems for 6d. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. MacLean, S. and Garioch, Robert. Seventeen Poems for Sixpence [second issue with corrections]. Edinburgh: Chalmers Press, 1940. 1943 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir agus Dàin Eile. Glasgow: William MacLellan, 1943. 1971 MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. London: Victor Gollancz, 1971. MacLean, S. Poems to Eimhir, translated from the Gaelic by Iain Crichton Smith. (Northern House Pamphlet Poets, 15). Newcastle upon Tyne: Northern House, 1971. 1977 MacLean, S. Reothairt is Contraigh: Taghadh de Dhàin 1932-72 /Spring tide and Neap tide: Selected Poems 1932-72. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1977. 1987 MacLean, S. Poems 1932-82. Philadelphia: Iona Foundation, 1987. 1989 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh / From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. Manchester: Carcanet, 1989. 1991 MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/ From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and English. London: Vintage, 1991. 1999 MacLean, S. Eimhir. Stornoway: Acair, 1999. MacLean, S. O Choille gu Bearradh/From Wood to Ridge: Collected Poems in Gaelic and in English translation. Manchester and Edinburgh: Carcanet/Birlinn, 1999. 2002 MacLean, S. Dàin do Eimhir/Poems to Eimhir, ed. Christopher Whyte. Glasgow: Association of Scottish Literary Studies, 2002. MacLean, S. Hallaig, translated by Seamus Heaney. Sleat: Urras Shomhairle, 2002. PROSE WRITINGS 1 1945 MacLean, S. ‘Bliain Shearlais – 1745’, Comar (Nollaig 1945). 1947 MacLean, S. ‘Aspects of Gaelic Poetry’ in Scottish Art and Letters, No. 3 (1947), 37. 1953 MacLean, S. ‘Am misgear agus an cluaran: A Drunk Man looks at the Thistle, by Hugh MacDiarmid’ in Gairm 6 (Winter 1953), 148. -

Shakespeare Merchant of Venice Unit 3: Detective Fiction Unit 4

Year 7 UNIT 1: Origins of Literature Unit 2: Shakespeare Unit 3: Detective Fiction Unit 4: The Effects of war and Conflict Unit 5: Novel Merchant of Venice OVERVIEW An introduction to, and exploration Students will begin to explore the effects of Students will consider how writers present the effects of TBC—Not of, a range of Greek Myths. Students are introduced to language and structure across a range of texts, war and conflict across poetry, fiction and non-fiction. being taught Students are introduced to the Shakespeare and read the whole considering the purpose and effects of writers’ They will be introduced to poetic form and methods in 2020-2021 structure and features of myths, text as a class. methods: used, develop analytical skills and then compare the in response to consider the plot and structure effects of war in two poems. Covid. and then write their own. Throughout the unit, students will: Adventures of Sherlock Holmes Develop their understanding of The Speckled Band short story AN exploration of Aim of unit Shakespeare’s language/grammar The Red Headed League Fiction: will be to: Orpheus and Eurydice patterns. The Final Problem Private Peaceful- Michael Morpurgo Explore Demeter and Persephone Explore characterisation. The Bone Sparrow characters, Theseus and the Minotaur Discuss and develop Other extracts Non-Fiction: ideas and Cyclops and Odysseus understanding of themes, ideas The Cuckoo’s Calling Major Gerald Ritchie 8th (Yorkshire) parachute regiment, themes in Prometheus and structural devices. A Murder is Announced letter to his sister (WW2) texts. Pandora’s Box Practice and develop their skills in Siegfried Sassoon: Letter of Defiance Analyse Hercules annotation and analysis. -

Appendix: More on Methodology

Appendix: More on Methodology Over the years my fi rst monograph, The Nature of Fascism (1991), has been charged by some academic colleagues with essentialism, reductionism, ‘revisionism’, a disinterest in praxis or material realities, and even a philosophical idealism which trivializes the human suffering caused by Hitler’s regime. It is thus worth offering the more methodologically self-aware readers, inveterately sceptical of the type of large-scale theorizing (‘metanarration’) that forms the bulk of Part One of this book, a few more paragraphs to substantiate my approach and give it some sort of intellectual pedigree. It can be thought of as deriving from three lines of methodological inquiry – and there are doubtless others that are complementary to them. One is the sophisticated (but inevitably contested) model of concept formation through ‘idealizing abstraction’1 which was elaborated piece-meal by Max Weber when wrestling with a number of the dilemmas which plagued the more epistemologically self-aware academics engaged in the late nineteenth-century ‘Methodenstreit’. This was a confl ict over methodology within the German human sciences that anticipated many themes of the late twentieth-century debate over how humanities disciplines should respond to postmodernism and the critical turn.2 The upshot of this line of thinking is that researchers must take it upon themselves to be as self-conscious as possible in the process of constructing the premises and ‘ideal types’ which shape the investigation of an area of external reality. Nor should they ever lose sight of the purely heuristic nature of their inquiry, and hence its inherently partial, incomplete nature. -

Chapter 15: Resources This Is by No Means an Exhaustive List. It's Just

Chapter 15: Resources This is by no means an exhaustive list. It's just meant to get you started. ORGANIZATIONS African Americans for Humanism Supports skeptics, doubters, humanists, and atheists in the African American community, provides forums for communication and education, and facilitates coordinated action to achieve shared objectives. <a href="http://aahumanism.net">aahumanism.net</a> American Atheists The premier organization laboring for the civil liberties of atheists and the total, absolute separation of government and religion. <a href="http://atheists.org">atheists.org</a> American Humanist Association Advocating progressive values and equality for humanists, atheists, and freethinkers. <a href="http://americanhumanist.org">americanhumanist.org</a> Americans United for Separation of Church and State A nonpartisan organization dedicated to preserving church-state separation to ensure religious freedom for all Americans. <a href="http://au.org">au.org</a> Atheist Alliance International A global federation of atheist and freethought groups and individuals, committed to educating its members and the public about atheism, secularism and related issues. <a href="http://atheistalliance.org">atheistalliance.org</a> Atheist Alliance of America The umbrella organization of atheist groups and individuals around the world committed to promoting and defending reason and the atheist worldview. <a href="http://atheistallianceamerica.org">atheistallianceamerica.org< /a> Atheist Ireland Building a rational, ethical and secular society free from superstition and supernaturalism. <a href="http://atheist.ie">atheist.ie</a> Black Atheists of America Dedicated to bridging the gap between atheism and the black community. <a href="http://blackatheistsofamerica.org">blackatheistsofamerica.org </a> The Brights' Net A bright is a person who has a naturalistic worldview. -

The Elements of Poet :Y

CHAPTER 3 The Elements of Poet :y A Poetry Review Types of Poems 1, Lyric: subjective, reflective poetry with regular rhyme scheme and meter which reveals the poet’s thoughts and feelings to create a single, unique impres- sion. Matthew Arnold, "Dover Beach" William Blake, "The Lamb," "The Tiger" Emily Dickinson, "Because I Could Not Stop for Death" Langston Hughes, "Dream Deferred" Andrew Marvell, "To His Coy Mistress" Walt Whitman, "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking" 2. Narrative: nondramatic, objective verse with regular rhyme scheme and meter which relates a story or narrative. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, "Kubla Khan" T. S. Eliot, "Journey of the Magi" Gerard Manley Hopkins, "The Wreck of the Deutschland" Alfred, Lord Tennyson, "Ulysses" 3. Sonnet: a rigid 14-line verse form, with variable structure and rhyme scheme according to type: a. Shakespearean (English)--three quatrains and concluding couplet in iambic pentameter, rhyming abab cdcd efe___~f gg or abba cddc effe gg. The Spenserian sonnet is a specialized form with linking rhyme abab bcbc cdcd ee. R-~bert Lowell, "Salem" William Shakespeare, "Shall I Compare Thee?" b. Italian (Petrarchan)--an octave and sestet, between which a break in thought occurs. The traditional rhyme scheme is abba abba cde cde (or, in the sestet, any variation of c, d, e). Elizabeth Barrett Browning, "How Do I Love Thee?" John Milton, "On His Blindness" John Donne, "Death, Be Not Proud" 4. Ode: elaborate lyric verse which deals seriously with a dignified theme. John Keats, "Ode on a Grecian Urn" Percy Bysshe Shelley, "Ode to the West Wind" William Wordsworth, "Ode: Intimations of Immortality" Blank Verse: unrhymed lines of iambic pentameter. -

Poetic Reformulations of Dwelling in Jo Shapcott, Alice Oswald, and Lavinia Greenlaw

Homecomings: Poetic reformulations of dwelling in Jo Shapcott, Alice Oswald, and Lavinia Greenlaw Janne Stigen Drangsholt, University of Stavanger Abstract In the study The Last of England?, Randall Stevenson refers to the idea of landscape as “the mainstay of poetic imagination” (Stevenson 2004:3). With the rise of the postmodern idiom, our relationship to the “scapes” that surround us has become increasingly problematic and the idea of place is also increasingly deferred and dis- placed. This article examines the relationship between self and “scapes” in the poetries of Jo Shapcott, Alice Oswald and Lavinia Greenlaw, who are all concerned with various “scapes” and who present different, yet connected, strategies for negotiating our relationships to them. Keywords: shifting territories; place; contemporary poetry; postmodernity In The Last of England?, Randall Stevenson points to how the mid- century renunciation of empire was followed by changes that need to be understood primarily in terms of loss. Each of these losses are conceived as marking the last of a certain kind of England, he says, and while another England gradually emerged, this was an England less unified by tradition and more open in outlook, lifestyle, and culture, in short, a place characterised by factors that render it more difficult to define (cf. Stevenson 2004: 1-10). Along with these losses in terms of national character, Stevenson holds, the English landscape also seemed to be increasingly imperilled. While this landscape had traditionally been “the mainstay of poetic imagination” it now seemed in danger of disappearing, as signalled in Philip Larkin’s poem “Going, Going”, where he laments an “England gone, / The shadows, the meadows, the lanes” (Stevenson 2004: 3). -

Identity and Women Poets of the Black Atlantic

IDENTITY AND WOMEN POETS OF THE BLACK ATLANTIC: MUSICALITY, HISTORY, AND HOME KAREN ELIZABETH CONCANNON SUBMITTED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR IN PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS SCHOOL OF ENGLISH SEPTEMBER 2014 i The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Karen E. Concannon to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. © 2014 The University of Leeds and K. E. Concannon ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful for the wisdom and assistance of Dr Andrew Warnes and Dr John Whale. They saw a potential in me from the start, and it has been with their patience, guidance, and eye-opening suggestions that this project has come to fruition. I thank Dr John McLeod and Dr Sharon Monteith for their close reading and constructive insights into the direction of my research. I am more than appreciative of Jackie Kay, whose generosity of time and spirit transcends the page to interpersonal connection. With this work, I honour Dr Harold Fein, who has always been a champion of my education. I am indebted to Laura Faile, whose loving friendship and joy in the literary arts have been for me a lifelong cornerstone. To Robert, Paula, and David Ohler, in each of my endeavours, I carry the love of our family with me like a ladder, bringing all things into reach. -

Gcse English Literature (8702)

GCSE ENGLISH LITERATURE (8702) Past and present: poetry anthology For exams from 2017 Version 1.0 June 2015 AQA_EngLit_GCSE_v08.indd 1 31/07/2015 22:14 AQA GCSE English Literature Past and present: poetry anthology All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing on any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the publisher, except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of the licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Notice to teachers: It is illegal to reproduce any part of this work in material form (including photocopying and electronic storage) except under the following circumstances: i) where you are abiding by a licence granted to your school or institution by the Copyright Licensing Agency; ii) where no such licence exists, or where you wish to exceed the terms of a licence, and you have gained the written permission of The Publishers Licensing Society; iii) where you are allowed to reproduce without permission under the provisions of Chapter 3 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Photo permissions 5 kieferpix / Getty Images, 6 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 8 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 9 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 11 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 12 Photos.com/Thinkstock, 13 Stuart Clarke/REX, 16 culture-images/Lebrecht, 16,© Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy, 17 Topfoto.co.uk, 18 Schiffer-Fuchs/ullstein -

Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning Was a Romantic Poet in Great Effect When Disclosing a Macabre Or Every Sense of the Word

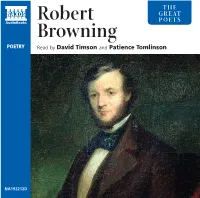

THE GREAT Robert POETS Browning POETRY Read by David Timson and Patience Tomlinson NA192212D 1 How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix 3:49 2 Life in a Love 1:11 3 A Light Woman 3:42 4 The Statue and the Bust 15:16 5 My Last Duchess 3:53 6 The Confessional 4:59 7 A Grammarian’s Funeral 8:09 8 The Pied Piper of Hamelin 7:24 9 ‘You should have heard the Hamelin people…’ 8:22 10 The Lost Leader 2:24 11 Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister 3:55 12 The Laboratory 3:40 13 Porphyria’s Lover 3:47 14 Evelyn Hope 3:49 15 Home Thoughts from Abroad 1:19 16 Pippa’s Song 0:32 Total time: 76:20 = David Timson = Patience Tomlinson 2 Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning was a romantic poet in great effect when disclosing a macabre or every sense of the word. He was an ardent evil narrative, as in The Laboratory, or The lover who wooed the poet Elizabeth Confessional or Porphyria’s Lover. Barrett despite fierce opposition from Sometimes Browning uses this matter- her tyrannical father, while as a poet – of-fact approach to reduce a momentous inheriting the mantle of Wordsworth, occasion to the colloquial – in The Keats and Shelley – he sought to show, Grammarian’s Funeral, for instance, in in the Romantic tradition, man’s struggle which a scholar has spent his life pursuing with his own nature and the will of God. knowledge at the expense of actually But Browning was no mere imitator of enjoying life itself. -

Archaeology, Classics and Contemporary Culture

7 ARCHAEOLOGY, CLASSICS AND CONTEMPORARY CULTURE But while all this troubles brewing what's the Prussian monarch doing? We read in his own writing, how, while all Europe geared for righting, England, Belgium, France, Russia but not of course his peaceful Prussia, what was Kaiser Wilhelm II up to? Excavating on Corfu, the scholar Kaiser on the scent of long lost temple pediment not filling trenches, excavating the trenches where the Gorgons waiting there in the trenches to supervise the unearthing of the Gorgons eyes. This isn't how warmongers are this professor in a panama stooping as the spades laid bare the first glimpses of' her snaky hair. The excavator with his find a new art treasure for mankind. (Tony Harrison, The Gaze of the Gorgon) At the turn of the century the German Kaiser bought a retreat on the island of Corfu which had belonged to Elizabeth, Empress of Austria prior to her assassination in 1899. She had brought with her a statue of Heinrich Heine, German Romantic poet and dissident Jew, rejected by his fatherland. The Kaiser evicted the statue again, not liking what it stood for (subversive radical democratic Jew) and, while Europe prepared for war, claimed he was excavating the pediment of a Greek temple (of the seventh century and dedicated to Artemis) which featured a giant Gorgon sculpted in stone. In the poem-film The Gaze of the Gorgon, Tony Harrison traces the fortunes of the statue of Heine transplanted through Europe, to its resting place in 169 CLASSICAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF GREECE Toulon, France. -

2021 PDF Catalogue

Spring & Summer CATALOGUE2021 Contents 3 Spring & Summer Selection 4 Featured Title When I Think of My Body as a Horse by Wendy Pratt 6 Featured Title Talking to Stanley on the Telephone by Michael Schmidt 9 The PB Bookshelf The AQI by David Tait 10 The North 11 New Poets List Ugly Bird by Lauren Hollingsworth-Smith Have a nice weekend I think you’re interesting by Lucy Holt Aunty Uncle Poems by Gboyega Odubanjo Takeaway by Georgie Woodhead 14 Forthcoming Titles 15 Subject Codes Pamphlet | 9781912196418 | £6 Black Mascara (Waterproof) eBook | 9781912196517 | £4.50 Published 1st Feb 2021 Rosalind Easton 34pp Black Mascara (Waterproof) is a glamorous and lively debut exploring Rosalind Easton grew up in Salisbury and relationships, popular culture, and the enduring power of teenage memories. now lives in South East London, where she works as an English teacher. After a first degree at Exeter University, she trained as Full of wicked invention. – Imtiaz Dharker a dance teacher and spent several years Love and the possibilities of love and intimacy are examined and celebrated teaching tap, modern and ballet before completing her PGCE at Bristol and MA at and quotidian adventures like bra fittings and running mascara are given the Goldsmiths. She has recently completed her power of myth. – Ian McMillan PhD thesis on Sarah Waters. Black Mascara (Waterproof) is her first collection. Witty, sexy poems that strut across the page – Natalie Whittaker Pamphlet | 9781912196425 | £6 In Your Absence eBook | 9781912196524 | £4.50 Published 1st Feb 2021 Jill Penny 36pp In Your Absence is a response to a year of bereavement, a murder and a trial, Jill Penny is from a touring theatre and estrangements, departures and insights.