Identity and Women Poets of the Black Atlantic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laura Chrisman - 9781526137579 Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 10/02/2021 01:51:05PM Via Free Access Prelims 21/12/04 9:25 Am Page I

Laura Chrisman - 9781526137579 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 10/02/2021 01:51:05PM via free access prelims 21/12/04 9:25 am Page i Postcolonial contraventions Laura Chrisman - 9781526137579 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 10/02/2021 01:51:05PM via free access prelims 21/12/04 9:25 am Page ii For my parents, Gale and Robert Chrisman Laura Chrisman - 9781526137579 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 10/02/2021 01:51:05PM via free access prelims 21/12/04 9:25 am Page iii Postcolonial contraventions Cultural readings of race, imperialism and transnationalism LAURA CHRISMAN Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Laura Chrisman - 9781526137579 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 10/02/2021 01:51:05PM via free access prelims 21/12/04 9:25 am Page iv Copyright © Laura Chrisman 2003 The right of Laura Chrisman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication -

Urging All of Us to Open Our Minds and Hearts So That We Can Know Beyond

CHAPTER 1 HOLISTIC READING We have left the land and embarked. We have burned our bridges behind us- indeed we have gone farther and destroyed the land behind us. Now, little ship, look out! Beside you is the ocean: to be sure, it does not always roar, and at times it lies spread out like silk and gold and reveries of graciousness. But hours will come when you realize that it is infinite and that there is nothing more awesome than infinity... Oh, the poor bird that felt free now strikes the walls of this cage! Woe, when you feel homesick for the land as if it had offered more freedom- and there is no longer any ―land.‖ - Nietzsche Each man‘s life represents a road toward himself, an attempt at such a road, the intimation of a path. No man has ever been entirely and completely himself. Yet each one strives to become that- one in an awkward, the other in a more intelligent way, each as best he can. Each man carries the vestiges of his birth- the slime and eggshells of his primeval past-… to the end of his days... Each represents a gamble on the part of nature in creation of the human. We all share the same origin, our mothers; all of us come in at the same door. But each of us- experiments of the depths- strives toward his own destiny. We can understand one another; but each is able to interpret himself alone. – Herman Hesse 1 In this chapter I suggest a new method of reading, which I call “holistic reading.” Building on the spiritual model of the Self offered by Jiddu Krishnamurti and the psychological model of “self” offered by Dr. -

The Rhetoric of Recovery in Africarribbean Women's Poetry

APOCRYPHA OF NANNY'S SECRETS APOCRYPHA OF NANNY'S SECRETS: THE RHETORIC OF RECOVERY IN AFRICARIBBEAN WOMEN'S POETRY. By DANNABANG KUWABONG A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy MCMASTER UNIVERSITY ~ Copyright by Dannabang Kuwabong September 1997. DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (1997) MCMASTER UNIVERSITY (ENGLISH) HAMILTON, ONTARIO TITLE: APOCRYPHA OF NANNY'S SECRETS: THE RHETORIC OF RECOVERY IN AFRICARIBBEAN WOMEN'S POETRY. AUTHOR: DANNABANG KUWABONG, B.A. (GHANA) M.LITT (STIRLING) SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR LORRAINE YORK NUMBER OF PAGES: viii, 295. ii AMISE€R€/(DEDICATION) N boarang na de a gban nga N nang di dogee segi baare ko Ng poga Hawa, aning te biiri: Mwinidiayeh, Angtuonq.mwini, Delemwini, aning ba nabaale nang ba la kyebe--Matiesi Kuwabong. Ka ba anang da ba are N puoreng a puoro kpiangaa yaga kora ma, N ba teere ka N danaang tuong baare a toma nga. Le zuing, N de la a tiizis nga puore ning ba bareka. (I wish to dedicate this work to my wife, Hawa, and our children: Mwinidiayeh, Angtuongmwini, and Delemwini, and their grandfather who is no longer alive--Matthais Kuwabong. If they had not stood solidly by me, and constantly prayed for me, I would not have been able to complete this thesis. On account of that, I offer the thesis to them). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Hau do I talk when there are no words say it again spicy words ride on spicy sounds say it again and there are times for such feasts but not today for now I surrender to what I have done but so have we this thesis treats unsalted words boiled on stones of herstory given on the day of sound starvation amidst drums of power this thesis feeds on bleeding words of sisters of the sun without whose pain i have no re-membering negations to them I offer thanksgiving for lending me their sighs but una mot bear wit mi. -

Death and Dying in 20Th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2013 Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Stoneberg-Cooper, C. A.(2013). Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2440 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOING HARD, GOING EASY, GOING HOME: DEATH AND DYING IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AFRICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper Bachelor of Arts University of Oregon, 2001 Master of Arts University of California, San Diego, 2003 Master of Arts New York University, 2005 Master of Social Work University of South Carolina, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2013 Accepted by: Qiana Whitted, Major Professor Kwame Dawes, Committee Member Folashade Alao, Committee Member Bobby Donaldson, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper, 2013 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my family and friends, often one and the same, both living and dead, whose successes and struggles have made the completion of this work possible. -

CWC Newsletter Summer (July:Aug) 2020

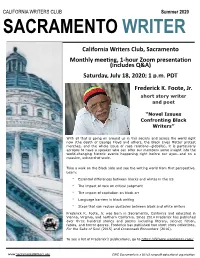

CALIFORNIA WRITERS CLUB Summer 2020 SACRAMENTO WRITER California Writers Club, Sacramento Monthly mee7ng, 1-hour Zoom presenta7on (includes Q&A) Saturday, July 18, 2020; 1 p.m. PDT Frederick K. Foote, Jr. short story writer and poet “Novel Issues Confronting Black Writers” With all that is going on around us in this society and across the world right now (the death of George Floyd and others, the Black Lives Matter protest marches, and the whole issue of race relations--globally), it is particularly apropos to have a speaker who can offer our members some insight into the world-changing historic events happening right before our eyes--and on a massive, unheard-of scale. Take a walk on the Black side and see the writing world from that perspective. Learn: • Essential differences between blacks and whites in the US • The impact of race on critical judgment • The impact of capitalism on black art • Language barriers in black writing • Steps that can reduce obstacles between black and white writers Frederick K. Foote, Jr. was born in Sacramento, California and educated in Vienna, Virginia, and northern California. Since 2014 Frederick has published over three hundred stories and poems including literary, science fiction, fables, and horror genres. Frederick has published two short story collections, For the Sake of Soul (2015) and Crossroads Encounters (2016). To see a list of Frederick’s publications, go to https://fkfoote.wordpress.com/ www.SacramentoWriters.org CWC Sacramento is a 501c3 nonprofit educational organization First Friday Networking Zoom July 3, 2020 at 10 a.m. Mini-Crowdsource Opportunity The CWC First Friday Zoom network meeting will be an opportunity to bring your most intractable, gruesome, horrendous, writing challenge to our forum of compassionate writers for solution. -

Copyright by Letitia Hopkins 2014

Copyright by Letitia Hopkins 2014 The Thesis committee for Letitia Hopkins Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: For My People ~ Margaret Walker ~ Lithographs by Elizabeth Catlett: A Consideration APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: ________________________________________________________________ Edward Chambers ________________________________________________________________ Cherise Smith For My People ~ Margaret Walker ~ Lithographs by Elizabeth Catlett: A Consideration by Letitia Hopkins, B.S.; M.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2014 Abstract For My People ~ Margaret Walker ~ Lithographs by Elizabeth Catlett: A Consideration Letitia Hopkins, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2014 Supervisor: Edward Chambers This thesis examines the 1992 Limited Edition Collection prints artist Elizabeth Catlett (American, 1915 – 2012) created to illustrate Margaret Walker's poem, For My People. The author analyzes Catlett’s images in terms of the ways in which they both document as well as reflect on the Black experience, and the ways in which her practice both anticipated and chimed with, the Black Arts Movement. Alongside a consideration of Catlett and her work, the author discusses the related significance of Margaret Walker (American, 1915 – 1998) and her poem, For My People, and the ways in which it was in so many ways the -

The Poetry of Rita Dove

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1999 Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove Carol Keyes University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Keyes, Carol, "Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove" (1999). Doctoral Dissertations. 2107. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMi films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICAL EXILE in the UNITED KINGDOM Al50by Mark Israel

SOUTH AFRICAN POLITICAL EXILE IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Al50by Mark Israel INTERNATIONAL VICTIMOLOGY (co-editor) South African Political Exile in the United Kingdom Mark Israel SeniorLecturer School of Law TheFlinders University ofSouth Australia First published in Great Britain 1999 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-1-349-14925-4 ISBN 978-1-349-14923-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-14923-0 First published in the United States of Ameri ca 1999 by ST. MARTIN'S PRESS, INC., Scholarly and Reference Division. 175 Fifth Avenue. New York. N.Y. 10010 ISBN 978-0-312-22025-9 Library of Congre ss Cataloging-in-Publication Data Israel. Mark. 1965- South African political exile in the United Kingdom / Mark Israel. p. cm. Include s bibliographical references and index . ISBN 978-0-312-22025-9 (cloth) I. Political refugees-Great Britain-History-20th century. 2. Great Britain-Exiles-History-20th century. 3. South Africans -Great Britain-History-20th century. I. Title . HV640.5.S6I87 1999 362.87'0941-dc21 98-32038 CIP © Mark Israel 1999 Softcover reprint of the hardcover Ist edition 1999 All rights reserved . No reprodu ction. copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publicat ion may be reproduced. copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provision s of the Copyright. Design s and Patents Act 1988. or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency . -

Steve Kuhn Trance Mp3, Flac, Wma

Steve Kuhn Trance mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Trance Country: Japan Released: 1975 Style: Space-Age, Modal MP3 version RAR size: 1269 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1491 mb WMA version RAR size: 1348 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 101 Other Formats: MP1 AAC XM AC3 APE VQF VOC Tracklist A1 Trance 5:54 A2 A Change Of Face 4:56 A3 Squirt 3:00 A4 The Sandhouse 3:45 B1 Something Everywhere 7:47 B2 Silver 2:54 B3 The Young Blade 6:15 B4 Life's Backward Glance 3:08 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – ECM Records GmbH Recorded At – Generation Sound Studios Credits Cover, Design – Frieder Grindler Drums – Jack DeJohnette Electric Bass – Steve Swallow Mixed By – Jan Erik Kongshaug Percussion – Sue Evans Photography By – Odd Geirr Saether* Piano, Electric Piano, Composed By – Steve Kuhn Producer – Manfred Eicher Recorded By – Tony May Notes Recorded November 11 and 12, 1974 at Generation Sound Studios, New York City Jack DeJohnette courtesy of Prestige Records An ECM Production P 1975 ECM Records GmbH Printed in W. Germany Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Steve Trance (LP, ECM 1052 ST ECM Records ECM 1052 ST Germany 1975 Kuhn Album) Steve Trance (CD, UCCU-5248 ECM Records UCCU-5248 Japan 2004 Kuhn Album, RE, RM) Steve Trance (LP, 25MJ 3347 ECM Records 25MJ 3347 Japan 1975 Kuhn Album) ECM 1052, 987 Steve Trance (CD, ECM Records, ECM 1052, 987 Germany Unknown 1774 Kuhn Album, RE) ECM Records 1774 Trance (CD, Steve UCCU-5750 Album, Ltd, RE, ECM Records UCCU-5750 Japan 2016 Kuhn SHM) Related Music albums to Trance by Steve Kuhn Miroslav Vitous - Universal Syncopations Jack DeJohnette's Special Edition - Inflation Blues John Surman - Free And Equal Gary Burton & Friends - Six Pack Jack DeJohnette - New Directions Steve Kuhn / Sheila Jordan Band - Playground John Abercrombie / Dave Holland / Jack DeJohnette - Gateway 2 Terje Rypdal / Miroslav Vitous / Jack DeJohnette - Terje Rypdal / Miroslav Vitous / Jack DeJohnette. -

The Black Women's Contribution to the Harlem Renaissance 1919-1940

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University Abd El Hamid Ibn Badis Faculty of Foreign Languages English Language The Black Women's Contribution to the Harlem Renaissance 1919-1940 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master in Literature and Interdisciplinary Approaches Presented By: Rahma ZIAT Board of Examiners: Chairperson: Dr. Belghoul Hadjer Supervisor: Djaafri Yasmina Examiner: Dr. Ghaermaoui Amel Academic Year: 2019-2020 i Dedication At the outset, I have to thank “Allah” who guided and gave me the patience and capacity for having conducted this research. I would like to dedicate this dissertation to my family and my friends. A very special feeling of gratitude to my loving father, and mother whose words of encouragement and push for tenacity ring in my ears. To my grand-mother, for her eternal love. Also, my sisters and brother, Khadidja, Bouchra and Ahmed who inspired me to be strong despite many obstacles in life. To a special person, my Moroccan friend Sami, whom I will always appreciate his support and his constant inspiration. To my best friend Fethia who was always there for me with her overwhelming love. Acknowledgments Foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Mrs.Djaafri for her continuous support in my research, for her patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge. Her guidance helped me in all the time of research and writing of this thesis. I could not have imagined having a better advisor and mentor for dissertation. I would like to deeply thank Mr. -

A Narrative of Augusta Baker's Early Life and Her Work As a Children's Librarian Within the New York Public Library System B

A NARRATIVE OF AUGUSTA BAKER’S EARLY LIFE AND HER WORK AS A CHILDREN’S LIBRARIAN WITHIN THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY SYSTEM BY REGINA SIERRA CARTER DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Policy Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor James Anderson, Chair Professor Anne Dyson Professor Violet Harris Associate Professor Yoon Pak ABSTRACT Augusta Braxston Baker (1911-1998) was a Black American librarian whose tenure within the New York Public Library (NYPL) system lasted for more than thirty years. This study seeks to shed light upon Baker’s educational trajectory, her career as a children’s librarian at NYPL’s 135th Street Branch, her work with Black children’s literature, and her enduring legacy. Baker’s narrative is constructed through the use of primary source materials, secondary source materials, and oral history interviews. The research questions which guide this study include: 1) How did Baker use what Yosso described as “community cultural wealth” throughout her educational trajectory and time within the NYPL system? 2) Why was Baker’s bibliography on Black children’s books significant? and 3) What is her lasting legacy? This study uses historical research to elucidate how Baker successfully navigated within the predominantly White world of librarianship and established criteria for identifying non-stereotypical children’s literature about Blacks and Black experiences. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Philippians 4:13 New Living Translation (NLT) ”For I can do everything through Christ,[a] who gives me strength.” I thank GOD who is my Everything. -

Latino American Literature in the Classroom

Latino American Literature in the Classroom Copyright 2002 by Delia Poey. This work is licensed under a modified Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. You are free to electronically copy, distribute, and transmit this work if you at- tribute authorship. However, all printing rights are reserved by the University Press of Florida (http://www.upf.com). Please contact UPF for information about how to ob- tain copies of the work for print distribution. You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the University Press of Florida. Nothing in this license impairs or restricts the author’s moral rights. Florida A&M University, Tallahassee Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton Florida Gulf Coast University, Ft. Myers Florida International University, Miami Florida State University, Tallahassee University of Central Florida, Orlando University of Florida, Gainesville University of North Florida, Jacksonville University of South Florida, Tampa University of West Florida, Pensacola This page intentionally left blank Latino American Literature in the Classroom The Politics of Transformation Delia Poey University Press of Florida Gainesville · Tallahassee · Tampa · Boca Raton Pensacola · Orlando · Miami · Jacksonville · Ft. Myers Copyright 2002 by Delia Poey Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper All rights reserved 07 06 05 04 03 02 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Poey, Delia.