The Poetry of Rita Dove

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor RESEARCH IN MEDIEVAL CULTURE Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Medieval Institute Publications is a program of The Medieval Institute, College of Arts and Sciences Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor MEDIEVAL INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS Western Michigan University Kalamazoo Copyright © 2015 by the Board of Trustees of Western Michigan University All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Taylor, Robert A. (Robert Allen), 1937- Bibliographical guide to the study of the troubadours and old Occitan literature / Robert A. Taylor. pages cm Includes index. Summary: "This volume provides offers an annotated listing of over two thousand recent books and articles that treat all categories of Occitan literature from the earli- est enigmatic texts to the works of Jordi de Sant Jordi, an Occitano-Catalan poet who died young in 1424. The works chosen for inclusion are intended to provide a rational introduction to the many thousands of studies that have appeared over the last thirty-five years. The listings provide descriptive comments about each contri- bution, with occasional remarks on striking or controversial content and numerous cross-references to identify complementary studies or differing opinions" -- Pro- vided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-58044-207-7 (Paperback : alk. paper) 1. Provençal literature--Bibliography. 2. Occitan literature--Bibliography. 3. Troubadours--Bibliography. 4. Civilization, Medieval, in literature--Bibliography. -

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

Letters Mingle Soules

Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991) Volume 8 Issue 1 Syracuse Scholar Spring 1987 Article 2 5-15-1987 Letters Mingle Soules Ben Howard Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/suscholar Recommended Citation Howard, Ben (1987) "Letters Mingle Soules," Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991): Vol. 8 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://surface.syr.edu/suscholar/vol8/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse Scholar (1979-1991) by an authorized editor of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Howard: Letters Mingle Soules Letters Mingle Soules Si1; mure than kisses) letters mingle Soules; Fm; thus friends absent speake. -Donne, "To Sir Henry Wotton" BEN HOWARD EW LITERARY FORMS are more inviting than the familiar IF letter. And few can claim a more enduring appeal than that imi tation of personal correspondence, the letter in verse. Over the centu ries, whether its author has been Horace or Ovid, Dryden or Pope, Auden or Richard Howard, the verse letter has offered a rare mixture of dignity and familiarity, uniting graceful talk with intimate revela tion. The arresting immediacy of the classic verse epistles-Pope's to Arbuthnot, Jonson's to Sackville, Donne's to Watton-derives in part from their authors' distinctive voices. But it is also a quality intrinsic to the genre. More than other modes, the verse letter can readily com bine the polished phrase and the improvised excursus, the studied speech and the wayward meditation. The richness of the epistolary tradition has not been lost on con temporary poets. -

Death and Dying in 20Th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2013 Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Stoneberg-Cooper, C. A.(2013). Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2440 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOING HARD, GOING EASY, GOING HOME: DEATH AND DYING IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AFRICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper Bachelor of Arts University of Oregon, 2001 Master of Arts University of California, San Diego, 2003 Master of Arts New York University, 2005 Master of Social Work University of South Carolina, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2013 Accepted by: Qiana Whitted, Major Professor Kwame Dawes, Committee Member Folashade Alao, Committee Member Bobby Donaldson, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper, 2013 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my family and friends, often one and the same, both living and dead, whose successes and struggles have made the completion of this work possible. -

Donald Hall – America’S New Poet Laureate the Library of Congress Has Named Donald Hall As the Nation's Fourteenth Poet Laureate

CALENDAR OF EVENTS THROUGH AUGUST 11 SEPTEMBER 30 MARCH 21 – 23, 2007 Catherine Borg, diazo prints on paper 27th Annual GAA Nomination 27th Annual Governor’s Arts Awards & OXS exhibit, NAC, Carson City Packets deadline OASIS Conference, Reno Locations & Time, TBA AUGUST 15 NOVEMBER 15 ARTS NEWS Jackpot Grants postmark deadline Letter of Intent for FY08 Challenge MAY 21 – 24, 2007 (for projects October 1 – December 31, Grants postmark deadline FY08 Grants and Folklife 2006) Apprenticeship Panel Meetings Jackpot Grants postmark deadline Locations & Time, TBA AIE BETA Grants (formerly Professional (for projects January 1 – March 30, Development Grants) postmark deadline 2007) JUNE 2 – 4, 2007 (for projects October 1 – December 31, Americans for the Arts 2006) AIE BETA Grants postmark deadline 2007 Annual Convention (for projects January 1 – March 30, Flamingo Las Vegas, Las Vegas SEPTEMBER 11 2007) GAA Visual Arts Commission deadline Please check the NAC website for calendar, agency and news updates at www.NevadaCulture.org. Donald Hall – America’s New Poet Laureate _________________________________________________________________________________________ The Library of Congress has named Donald Hall as the nation's fourteenth Poet Laureate. A resident of Danbury, NH, Hall has published numerous books of poetry, including Without: Poems, released in 1998 on the third anniversary of his wife and fellow poet Jane Kenyon’s death from leukemia. Hall has written children’s books, books on baseball, autobiographical works, short stories and plays. Poetry editor of The Paris Review during its early years, Hall’s list of anthologies and awards is extensive. The Library of Congress deliberately avoids attaching specific duties to the post of Poet Laureate. -

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Introduction Writer Biographies for B&N Classics A. Michael Matin Is a Professor in the English Department of Warren Wilson

Introduction Writer Biographies for B&N Classics A. Michael Matin is a professor in the English Department of Warren Wilson College, where he teaches late-nineteenth-century and twentieth-century British and Anglophone postcolonial literature. His essays have appeared in Studies in the Novel, The Journal of Modern Literature, Scribners’ British Writers, Scribners’ World Poets, and the Norton Critical Edition of Kipling’s Kim. Matin wrote Introductions and Notes for Conrad’s Lord Jim and Heart of Darkness and Selected Short Fiction. Alfred Mac Adam, Professor at Barnard College–Columbia University, teaches Latin American and comparative literature. He is a translator of Latin American fiction and writes extensively on art. He has written an Introductions and Notes for H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine and The Invisible Man and The War of the Worlds, Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ Les Liasons Dangereuses, and Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. Amanda Claybaugh is Associate Professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University. She is currently at work on a project that considers the relation between social reform and the literary marketplace in the nineteenth-century British and American novel. She has written an Introductions and Notes for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. Amy Billone is Assistant Professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville where her specialty is 19th Century British literature. She is the author of Little Songs: Women, Silence and the Nineteenth-Century Sonnet and has published articles on both children’s literature and poetry in numerous places. She wrote the Introduction and Notes for Peter Pan by J. -

Women's History Is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating in Communities

Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook Prepared by The President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History “Just think of the ideas, the inventions, the social movements that have so dramatically altered our society. Now, many of those movements and ideas we can trace to our own founding, our founding documents: the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. And we can then follow those ideas as they move toward Seneca Falls, where 150 years ago, women struggled to articulate what their rights should be. From women’s struggle to gain the right to vote to gaining the access that we needed in the halls of academia, to pursuing the jobs and business opportunities we were qualified for, to competing on the field of sports, we have seen many breathtaking changes. Whether we know the names of the women who have done these acts because they stand in history, or we see them in the television or the newspaper coverage, we know that for everyone whose name we know there are countless women who are engaged every day in the ordinary, but remarkable, acts of citizenship.” —- Hillary Rodham Clinton, March 15, 1999 Women’s History is Everywhere: 10 Ideas for Celebrating In Communities A How-To Community Handbook prepared by the President’s Commission on the Celebration of Women in American History Commission Co-Chairs: Ann Lewis and Beth Newburger Commission Members: Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole, J. Michael Cook, Dr. Barbara Goldsmith, LaDonna Harris, Gloria Johnson, Dr. Elaine Kim, Dr. -

Protective Pastoral: Innocence and Female Experience in William Blake's Songs and Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market June Sturrock

Colby Quarterly Volume 30 Article 4 Issue 2 June June 1994 Protective Pastoral: Innocence and Female Experience in William Blake's Songs and Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market June Sturrock Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 30, no.2, June 1994, p.98-108 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sturrock: Protective Pastoral: Innocence and Female Experience in William B Protective Pastoral: Innocence and Female Experience in William Blake's Songs and Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market by JlTNE STURROCK IIyEA, THOUGH I walk through the valley ofthe shadow ofdeath, I shall fear no evil, for thou art with me, thy rod and thy staffthey comfort me." The twenty-third psalm has been offered as comfort to the sick and the grieving for thousands ofyears now, with its image ofGod as the good shepherd and the soul beloved ofGod as the protected sheep. This psalm, and such equally well-known passages as Isaiah's "He shall feed his flock as a shepherd: he shall gather the lambs in his arms" (40. 11), together with the specifically Christian version: "I am the good shepherd" (John 10. 11, 14), have obviously affected the whole pastoral tradition in European literature. Among othereffects the conceptofGod as shepherd has allowed for development of the protective implications of classical pastoral. The pastoral idyll-as opposed to the pastoral elegy suggests a safe, rural world in that corruption, confusion and danger are placed elsewhere-in the city. -

CWC Newsletter Summer (July:Aug) 2020

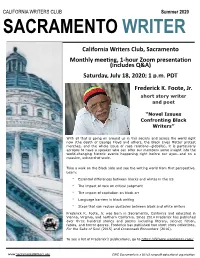

CALIFORNIA WRITERS CLUB Summer 2020 SACRAMENTO WRITER California Writers Club, Sacramento Monthly mee7ng, 1-hour Zoom presenta7on (includes Q&A) Saturday, July 18, 2020; 1 p.m. PDT Frederick K. Foote, Jr. short story writer and poet “Novel Issues Confronting Black Writers” With all that is going on around us in this society and across the world right now (the death of George Floyd and others, the Black Lives Matter protest marches, and the whole issue of race relations--globally), it is particularly apropos to have a speaker who can offer our members some insight into the world-changing historic events happening right before our eyes--and on a massive, unheard-of scale. Take a walk on the Black side and see the writing world from that perspective. Learn: • Essential differences between blacks and whites in the US • The impact of race on critical judgment • The impact of capitalism on black art • Language barriers in black writing • Steps that can reduce obstacles between black and white writers Frederick K. Foote, Jr. was born in Sacramento, California and educated in Vienna, Virginia, and northern California. Since 2014 Frederick has published over three hundred stories and poems including literary, science fiction, fables, and horror genres. Frederick has published two short story collections, For the Sake of Soul (2015) and Crossroads Encounters (2016). To see a list of Frederick’s publications, go to https://fkfoote.wordpress.com/ www.SacramentoWriters.org CWC Sacramento is a 501c3 nonprofit educational organization First Friday Networking Zoom July 3, 2020 at 10 a.m. Mini-Crowdsource Opportunity The CWC First Friday Zoom network meeting will be an opportunity to bring your most intractable, gruesome, horrendous, writing challenge to our forum of compassionate writers for solution. -

The Visionary Company

WILLIAM BLAKE 49 rible world offering no compensations for such denial, The] can bear reality no longer and with a shriek flees back "unhinder' d" into her paradise. It will turn in time into a dungeon of Ulro for her, by the law of Blake's dialectic, for "where man is not, nature is barren"and The] has refused to become man. The pleasures of reading The Book of Thel, once the poem is understood, are very nearly unique among the pleasures of litera ture. Though the poem ends in voluntary negation, its tone until the vehement last section is a technical triumph over the problem of depicting a Beulah world in which all contraries are equally true. Thel's world is precariously beautiful; one false phrase and its looking-glass reality would be shattered, yet Blake's diction re mains firm even as he sets forth a vision of fragility. Had Thel been able to maintain herself in Experience, she might have re covered Innocence within it. The poem's last plate shows a serpent guided by three children who ride upon him, as a final emblem of sexual Generation tamed by the Innocent vision. The mood of the poem culminates in regret, which the poem's earlier tone prophe sied. VISIONS OF THE DAUGHTERS OF ALBION The heroine of Visions of the Daughters of Albion ( 1793), Oothoon, is the redemption of the timid virgin Thel. Thel's final griefwas only pathetic, and her failure of will a doom to vegetative self-absorption. Oothoon's fate has the dignity of the tragic. -

With Jane and Without: an Interview with Donald Hall, Non-Fiction By

With Jane and Without: An Interview with Donald Hall By Jeffrey S. Cramer ANYONE KENYON ACQUAINTED cannot help but stand WITH in awe THE of the STORY irony which, OF if DONALD it HALL AND JANE appeared in fiction, would appall by its tear-jerking manipulation. The reality, as I stand before Jane Kenyon's grave, leaves me sad dened and numb. The lines on their shared stone are from Kenyon's poem, "After noon at MacDowell. " Although she wrote it with Hall in mind when he, as he has said, was ''supposed to die," they now stand in testimony to Kenyon, and look, mistakenly, like words he must have written for her: I BELIEVE IN THE MIRACLES OF ART BUT WHAT PRODIGY WILL KEEP YOU SAFE BESIDE ME Four miles North of the Proctor cemetery on Route 4, just past Eagle Pond Road, in the shadow of Ragged Mountain, is Eagle Pond Farm. There is no sign, no name on the mailbox, but the satellite dish over whelming the North side yard announces the home of a man who cannot live unconnected to his beloved baseball games. The living room seems truly a living room, a room lived in, infor mal. It is surrounded, as would be expected, by books; an open book of pictures of sculpture by Henry Moore lays on the coffee table in front of the couch on which I sit. By the window Hall's chair faces the T.V. and VCR which must have received, recorded and replayed thousands of ballgames. The Glenwood stands nearby.