Nikki Giovanni

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Death and Dying in 20Th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2013 Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Stoneberg-Cooper, C. A.(2013). Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2440 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOING HARD, GOING EASY, GOING HOME: DEATH AND DYING IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AFRICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper Bachelor of Arts University of Oregon, 2001 Master of Arts University of California, San Diego, 2003 Master of Arts New York University, 2005 Master of Social Work University of South Carolina, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2013 Accepted by: Qiana Whitted, Major Professor Kwame Dawes, Committee Member Folashade Alao, Committee Member Bobby Donaldson, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper, 2013 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my family and friends, often one and the same, both living and dead, whose successes and struggles have made the completion of this work possible. -

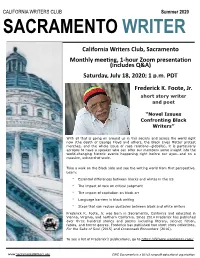

CWC Newsletter Summer (July:Aug) 2020

CALIFORNIA WRITERS CLUB Summer 2020 SACRAMENTO WRITER California Writers Club, Sacramento Monthly mee7ng, 1-hour Zoom presenta7on (includes Q&A) Saturday, July 18, 2020; 1 p.m. PDT Frederick K. Foote, Jr. short story writer and poet “Novel Issues Confronting Black Writers” With all that is going on around us in this society and across the world right now (the death of George Floyd and others, the Black Lives Matter protest marches, and the whole issue of race relations--globally), it is particularly apropos to have a speaker who can offer our members some insight into the world-changing historic events happening right before our eyes--and on a massive, unheard-of scale. Take a walk on the Black side and see the writing world from that perspective. Learn: • Essential differences between blacks and whites in the US • The impact of race on critical judgment • The impact of capitalism on black art • Language barriers in black writing • Steps that can reduce obstacles between black and white writers Frederick K. Foote, Jr. was born in Sacramento, California and educated in Vienna, Virginia, and northern California. Since 2014 Frederick has published over three hundred stories and poems including literary, science fiction, fables, and horror genres. Frederick has published two short story collections, For the Sake of Soul (2015) and Crossroads Encounters (2016). To see a list of Frederick’s publications, go to https://fkfoote.wordpress.com/ www.SacramentoWriters.org CWC Sacramento is a 501c3 nonprofit educational organization First Friday Networking Zoom July 3, 2020 at 10 a.m. Mini-Crowdsource Opportunity The CWC First Friday Zoom network meeting will be an opportunity to bring your most intractable, gruesome, horrendous, writing challenge to our forum of compassionate writers for solution. -

The Poetry of Rita Dove

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1999 Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove Carol Keyes University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Keyes, Carol, "Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove" (1999). Doctoral Dissertations. 2107. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMi films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Identity and Women Poets of the Black Atlantic

IDENTITY AND WOMEN POETS OF THE BLACK ATLANTIC: MUSICALITY, HISTORY, AND HOME KAREN ELIZABETH CONCANNON SUBMITTED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR IN PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS SCHOOL OF ENGLISH SEPTEMBER 2014 i The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Karen E. Concannon to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. © 2014 The University of Leeds and K. E. Concannon ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful for the wisdom and assistance of Dr Andrew Warnes and Dr John Whale. They saw a potential in me from the start, and it has been with their patience, guidance, and eye-opening suggestions that this project has come to fruition. I thank Dr John McLeod and Dr Sharon Monteith for their close reading and constructive insights into the direction of my research. I am more than appreciative of Jackie Kay, whose generosity of time and spirit transcends the page to interpersonal connection. With this work, I honour Dr Harold Fein, who has always been a champion of my education. I am indebted to Laura Faile, whose loving friendship and joy in the literary arts have been for me a lifelong cornerstone. To Robert, Paula, and David Ohler, in each of my endeavours, I carry the love of our family with me like a ladder, bringing all things into reach. -

Empowering Strategies at Home in the Works of Nikki Giovanni and Rita Dove

Empowering Strategies at Home in the Works of Nikki Giovanni and Rita Dove Maria Proitsaki Faculty of Human Sciences Thesis for Doctoral degree in English Mid Sweden University Sundsvall, 2017-09-28 Akademisk avhandling som med tillstånd av Mittuniversitetet i Sundsvall framläggs till offentlig granskning för avläggande av filosofie doktors torsdagen, den 28 september 2017, klockan 13.00, room M 102, Mittuniversitetet, campus Sundsvall. Seminariet kommer att hållas på engelska. Empowering Strategies at Home in the Works of Nikki Giovanni and Rita Dove © Maria Proitsaki, 2017-09-28 Printed by Mid Sweden University, Sundsvall ISSN: 1652-893X ISBN: 978-91-88527-27-1 Faculty of Human Sciences Mid Sweden University, 85170 Sundsvall Phone: +46 (0)10 142 80 00 Mid Sweden University Doctoral Thesis 270, 2017 For Iris, Martin, and Thomas The stars on my twig Acknowledgements My thesis project has been a bold endeavor and an adventurous journey that lasted far longer than I originally anticipated, so I am really pleased to have completed it. I am glad that, though life intervened on numerous occasions and my circumstances were often foreboding, I continued writing. I am sure I learned a lot about the world and myself that I would not have otherwise. Over time, many people contributed in different ways to my work and I am happy I have encountered them all. Back in school, via the poems of Kavafis, Karyotakis, Seferis, Elytis, and the ancient lyrics, my Greek teacher Christos Foundos showed me the way to the pleasures of poetry. At Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Prof. Ekaterini Georgoudaki handed me the seeds to this thesis on a pink post-it note, empowering me to believe that I could achieve beyond my gender and class limitations. -

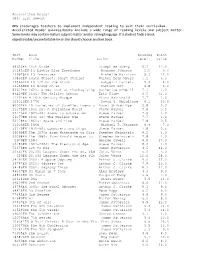

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Test List Report OHS encourages teachers to implement independent reading to suit their curriculum. Accelerated Reader quizzes/books include a wide range of reading levels and subject matter. Some books may contain mature subject matter and/or strong language. If a student finds a book objectionable/uncomfortable he or she should choose another book. Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 68630EN 10th Grade Joseph Weisberg 5.7 11.0 101453EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Maureen Johnson 5.0 9.0 136675EN 13 Treasures Michelle Harrison 5.3 11.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 135667EN 16 1/2 On the Block Babygirl Daniels 5.3 4.0 135668EN 16 Going on 21 Darrien Lee 4.8 6.0 53617EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 86429EN 1634: The Galileo Affair Eric Flint 6.5 31.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 7.7 1.0 104010EN 1776 David G. McCulloug 9.1 20.0 80002EN 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems o Naomi Shihab Nye 5.8 2.0 53175EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 53176EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Steve Parker 7.9 1.0 53177EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Steve Parker 7.7 1.0 53178EN 1960s: Space and Time Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 130068EN 1968 Michael T. Kaufman 9.9 7.0 53179EN 1970-90: Computers and Chips Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 36099EN The 1970s from Watergate to Disc Stephen Feinstein 8.2 1.0 36098EN The 1980s from Ronald Reagan to Stephen Feinstein 7.8 1.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Ad Jules Verne 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

Selected Poetry of Nikki Giovanni

SELECTED POETRY OF NIKKI GIOVANNI: A BURKEIAN ANALYSIS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas Estate University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS 37 Carolyn Tobola, B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1973 Tobola, Carolyn, Selected Poetry of Nikki Giovanni; A Burkeian Analysis. Master of Arts (Speech and Drama), August, 1973> 96 pp., bibliography, b-7 titles. In this study, Kenneth Burke's methods of dramatistic analysis is applied to the selected poetry of Nikki Giovanni, a Black contemporary female poet. The procedure, analysis of poetry for symbolic action, is a functional approach which focuses on the poetic language, Agency. The thesis, divided into four chapters, concentrates on discovery of the Purpose, a Black female motive, for the Act, Giovanni's poetry, in the Scene, contemporary Black America. Chapter I is an overview of Kenneth Burke and his drama- tistic method of analysis. The chapter includes an explana- tion of Burkeian terms pertinent to this study and a list of the nine poems which were categorically selected for this study. Also included in the chapter is a discussion of six procedural steps for poetic analysis. The final three steps are the most important in the procedure: "pun analysis," "rhetoric of rebirth," and "archytypal structure." Chapter II describes the Scene encompassing the Act. The circum- ference of the Scene is narrowed to include the following three areas: political and social, artistic, and familial and personal in order to determine the factors influencing Giovanni's Act. A historical account of the Civil Rights Movement describes "the social and political scene. -

Appalachian Studies Bibliography Cumulation 2013-June 2016 ______

Appalachian Studies Bibliography Cumulation 2013-June 2016 _____________________ CONTENTS Agriculture and Land Use ................................................................................................................3 Appalachian Studies.........................................................................................................................8 Archaeology and Physical Anthropology ......................................................................................14 Architecture, Historic Buildings, Historic Sites ............................................................................18 Arts and Crafts ..............................................................................................................................21 Biography .......................................................................................................................................27 Civil War, Military.........................................................................................................................29 Coal, Industry, Labor, Railroads, Transportation ..........................................................................37 Description and Travel, Recreation and Sports .............................................................................63 Economic Conditions, Economic Development, Economic Policy, Poverty ................................71 Education .......................................................................................................................................82 -

Literature for Composition Reading and Writing Arguments About Essays, Stories, Poems, and Plays

BARN.2138.bkfm.i-xxvi_BARN.2138.bkfm.i-xxvi 2/27/13 1:27 PM Page i INSTRUCTOR’S HANDBOOK TO ACCOMPANY Literature for Composition Reading and Writing Arguments About Essays, Stories, Poems, and Plays TENTH EDITION Edited by Sylvan Barnet Tufts University William Burto University of Massachusetts at Lowell William E. Cain Wellesley College Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York San Francisco Upper Saddle River Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid Milan Munich Paris Montreal Toronto Delhi Mexico City São Paulo Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo BARN.2138.bkfm.i-xxvi_BARN.2138.bkfm.i-xxvi 2/27/13 1:27 PM Page ii Vice President and Editor in Chief: Joseph P. Terry Senior Supplements Editor: Donna Campion Electronic Page Makeup: Grapevine Publishing Services, Inc. Instructor’s Handbook to Accompany Literature for Composition: Essays, Stories, Poems, and Plays, Tenth Edition, by Sylvan Barnet, William Burto, and William E. Cain. Copyright © 2014, 2011, 2007 Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Instructors may re- produce portions of this book for classroom use only. All other reproductions are strictly prohibited without prior permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10–online–15 14 13 12 ISBN 10: 0-321-84213-8 www.pearsonhighered.com ISBN 13: 978-0-321-84213-8 BARN.2138.bkfm.i-xxvi_BARN.2138.bkfm.i-xxvi 2/27/13 1:27 PM Page iii Contents Preface xv Using the “Short Views” and the “Overviews” xvii Guide to MyLiteratureLabTM xix The First Day 1 PART I Getting Started: From Response to Argument CHAPTER 1 How to Write an Effective Essay: A Crash Course 4 CHAPTER 2 The Writer as Reader 5 KATE CHOPIN Ripe Figs 5 LYDIA DAVIS City People 6 RAY BRADBURY August 2026: There Will Come Soft Rains 7 MICHELE SERROS Senior Picture Day 8 GUY DE MAUPASSANT The Necklace 9 GUY DE MAUPASSANT Hautot and Son 13 T. -

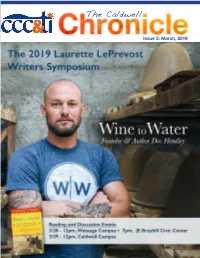

The Chronicle

The Caldwell Issue 3: March, 2019 March CCC&TI Hosts Author 6-8 Spring Break, Doc Hendley for Writers Symposium No Curriculum Classes 12 Caldwell Community College and Technical Institute will host Doc Hendley, author of NSLS Speaker Broadcast, Wine To Water: How One Man Saved Himself While Trying to Save the World, for the 2019 Diamond Dallas Page, 7 p.m.; E-120 and W372-101 Laurette LePrevost Writers Symposium. 13 Grab-N-Go Workshop, Alco- The college will host a reading and discussion session with Hendley on Thursday, March 28 hol Awareness, 11:30 a.m. at 12 p.m. on CCC&TI’s Watauga Campus and at 7 p.m. at the J.E. Broyhill Civic Center in to 1 p.m. (Drop In); Caldwell Campus LRC Lenoir. On Friday, March 29, the college will host a reading and discussion with Hendley at 12 p.m. in the gym on the Caldwell Campus in Hudson. All events are free and open to the Watauga TRIO Deli, 12 p.m.; Student Lounge public. 19 Performing Artist Series, Der- The Symposium also will include book clubs focusing on Hendley’s Wine To Water on both ek Gripper, 1 p.m.; Caldwell campuses for students, faculty, staff and the community. Campus Recital Hall, B-100 NSLS Speaker Rebroadcast, The Watauga Campus in Boone will host its book club on Wednesday, March 20 from 2 p.m. Dr. Shefali Tsabary, 3 p.m.; Caldwell Campus, E-120 to 3 p.m. in the Watauga Campus library (Building W371). The Caldwell Campus in Hudson will host its book club at 12 p.m. -

Women's History Month Literary Scavenger Hunt

Ann Beattie Alice Munro Agatha Christie Harper Lee Sylvia Plath Emily Dickinson Edith Wharton Solmaz Sharif Mónica de la Torre Alice Walker Edna St. Vincent Millay Use your library’s resources to find Ada Limón Joy Harjo Elizabeth Bishop Margaret Atwood Maya Angelou Joan Didion Sandra Cisneros Zora Neale Hurston Octavia Butler Robin Hobb answers to the questions below about Jane Austen Sarah Waters Amy Tan Naomi Shihab Nye Kate Chopin Jhumpa Lahiri Mary OliverToni Morrison Zadie Smith women writers and poets and their Cecilia Vicuña Anne Bradstreet Emily Brontë Louise Erdrich Willa Cather Isabel Allende Charlotte Brontë Rita Dove Judy Blume Nikki Giovanni well-known works, which continue to Elizabeth Barrett Browning Gillian Flynn Joyce Carol Oates Beverly Cleary Layli Long Soldier Jamaica Kincaid Denise Levertov Jana Prikryl Julia Alvarez Jenny Xie Flannery O’Connor Tishani Doshi Adrienne Rich Hannah Rothschild Edwidge Danticat shape the history of literature today. Shirley Jackson Murasaki Shikibu Virginia Woolf Louisa May Alcott Tracy K. Smith Gwendolyn Brooks This author is known for her works on women and their relationships and her focus on power, injustice, and poverty. Her memoir, “Brother, I’m Dying” was a 2007 finalist for the National Book Award. She is a 2009 MacArthur fellow, and she won the 2019 St. Louis Literary Award. Who is she? A. Gillian Flynn B. Amy Tan C. Edwidge Danticat D. Sarah Waters This author made history as the first African American recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1993. She also famously said,” If there is a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, you must be the one to write it.” Who is she? A. -

"To Make a Poet Black Then Bid Him Sing"

To the Graduate Council: I am submitting a thesis/dissertation written by George Conley, Jr. entitled “To Make a Poet Black Then Bid Him Sing.” I have examined the electronic copy of this thesis and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a major in English. Earl S. Braggs, M.F. A., Chairperson We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Richard P Jackson, Ph.D. Sybil Baker, M.A., M.F.A. Accepted for the Graduate Council: ___________________________________ Stephanie Bellar, Interim Dean of The Graduate School “To make a poet Black then bid him sing” A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee, Chattanooga George Conley, Jr. May 2010 Copyright © 2010 by George Conley, Jr. All Rights Reserved ii Dedication I would like to dedicate this work to my loving wife, Anita Polk-Conley, for her undying support and devotion. She stood by me throughout this project. Without her love and belief in me, I surely would not be here today. iii Acknowledgements I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge the tremendous impact classroom instruction and workshops have had in shaping, not only my writing but, my desire and passion for the art. My professors, namely, Earl Braggs, Rick Jackson, and Sybil Baker equally shared their intensity for writing poetry and fiction. They also shared tried and proven techniques that separate a good writer from an average one and a great writer from a good one. Jackson’s determination to teach the necessity of the arc found in all great poems will forever stay in the forefront of my mind when creating my own work.