"To Make a Poet Black Then Bid Him Sing"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Death and Dying in 20Th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2013 Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature Chayah Amayala Stoneberg-Cooper University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Stoneberg-Cooper, C. A.(2013). Going Hard, Going Easy, Going Home: Death and Dying in 20th Century African American Literature. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2440 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOING HARD, GOING EASY, GOING HOME: DEATH AND DYING IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AFRICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper Bachelor of Arts University of Oregon, 2001 Master of Arts University of California, San Diego, 2003 Master of Arts New York University, 2005 Master of Social Work University of South Carolina, 2011 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2013 Accepted by: Qiana Whitted, Major Professor Kwame Dawes, Committee Member Folashade Alao, Committee Member Bobby Donaldson, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Chayah Stoneberg-Cooper, 2013 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my family and friends, often one and the same, both living and dead, whose successes and struggles have made the completion of this work possible. -

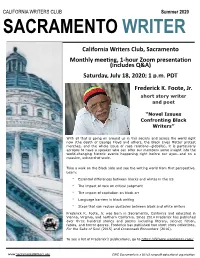

CWC Newsletter Summer (July:Aug) 2020

CALIFORNIA WRITERS CLUB Summer 2020 SACRAMENTO WRITER California Writers Club, Sacramento Monthly mee7ng, 1-hour Zoom presenta7on (includes Q&A) Saturday, July 18, 2020; 1 p.m. PDT Frederick K. Foote, Jr. short story writer and poet “Novel Issues Confronting Black Writers” With all that is going on around us in this society and across the world right now (the death of George Floyd and others, the Black Lives Matter protest marches, and the whole issue of race relations--globally), it is particularly apropos to have a speaker who can offer our members some insight into the world-changing historic events happening right before our eyes--and on a massive, unheard-of scale. Take a walk on the Black side and see the writing world from that perspective. Learn: • Essential differences between blacks and whites in the US • The impact of race on critical judgment • The impact of capitalism on black art • Language barriers in black writing • Steps that can reduce obstacles between black and white writers Frederick K. Foote, Jr. was born in Sacramento, California and educated in Vienna, Virginia, and northern California. Since 2014 Frederick has published over three hundred stories and poems including literary, science fiction, fables, and horror genres. Frederick has published two short story collections, For the Sake of Soul (2015) and Crossroads Encounters (2016). To see a list of Frederick’s publications, go to https://fkfoote.wordpress.com/ www.SacramentoWriters.org CWC Sacramento is a 501c3 nonprofit educational organization First Friday Networking Zoom July 3, 2020 at 10 a.m. Mini-Crowdsource Opportunity The CWC First Friday Zoom network meeting will be an opportunity to bring your most intractable, gruesome, horrendous, writing challenge to our forum of compassionate writers for solution. -

The Poetry of Rita Dove

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1999 Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove Carol Keyes University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Keyes, Carol, "Language's "bliss of unfolding" in and through history, autobiography and myth: The poetry of Rita Dove" (1999). Doctoral Dissertations. 2107. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2107 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMi films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Nikki Giovanni

Nikki Giovanni and if ever I touched a life I hope that life knows that I know that touching was and still is and will always be the true revolution “ — “When I Die” from My House (1972) Biography Quick Facts Nikki Giovanni was born on June 7, 1943 in Knoxville, Tennessee under * Born in 1943 her birth name, Yolande Cornelia Giovanni, Jr. She was raised in Cincin- nati, Ohio where she left high school as a junior in order to attend Fisk * Black” Rights University, a historically black institution. As an undergraduate, she poet, activist, became increasingly involved in politics surrounding race as well as art. and educator She involved herself with the Black Arts Movement and in 1964 led the * First published organizing of the influential civil rights organization, the Student Non- book of poetry violent Coordinating Committee (Reid 46). As she became more active was Black in the struggle surrounding race in the sixties she edited a student literary Judgment journal. During this time, Giovanni began to emerge as a revolutionary Black Rights poet. Giovanni’s poetry spans over thirty years, from her first book in 1968 to her most recent collection Blues For All the Changes (1998). In her most comprehensive work of poetry, The Selected Poems of Nikki Giovanni (1996), the reader experiences vast changes in a poet’s early contentious poetry and later, more personal poetry. This page was researched and submitted by Ryan Wahlberg and Bianca Ward on 5/23/01. 1 © 2009 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. The University of Minnesota is an equal opportunity educator and employer. -

Identity and Women Poets of the Black Atlantic

IDENTITY AND WOMEN POETS OF THE BLACK ATLANTIC: MUSICALITY, HISTORY, AND HOME KAREN ELIZABETH CONCANNON SUBMITTED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR IN PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS SCHOOL OF ENGLISH SEPTEMBER 2014 i The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Karen E. Concannon to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. © 2014 The University of Leeds and K. E. Concannon ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful for the wisdom and assistance of Dr Andrew Warnes and Dr John Whale. They saw a potential in me from the start, and it has been with their patience, guidance, and eye-opening suggestions that this project has come to fruition. I thank Dr John McLeod and Dr Sharon Monteith for their close reading and constructive insights into the direction of my research. I am more than appreciative of Jackie Kay, whose generosity of time and spirit transcends the page to interpersonal connection. With this work, I honour Dr Harold Fein, who has always been a champion of my education. I am indebted to Laura Faile, whose loving friendship and joy in the literary arts have been for me a lifelong cornerstone. To Robert, Paula, and David Ohler, in each of my endeavours, I carry the love of our family with me like a ladder, bringing all things into reach. -

Empowering Strategies at Home in the Works of Nikki Giovanni and Rita Dove

Empowering Strategies at Home in the Works of Nikki Giovanni and Rita Dove Maria Proitsaki Faculty of Human Sciences Thesis for Doctoral degree in English Mid Sweden University Sundsvall, 2017-09-28 Akademisk avhandling som med tillstånd av Mittuniversitetet i Sundsvall framläggs till offentlig granskning för avläggande av filosofie doktors torsdagen, den 28 september 2017, klockan 13.00, room M 102, Mittuniversitetet, campus Sundsvall. Seminariet kommer att hållas på engelska. Empowering Strategies at Home in the Works of Nikki Giovanni and Rita Dove © Maria Proitsaki, 2017-09-28 Printed by Mid Sweden University, Sundsvall ISSN: 1652-893X ISBN: 978-91-88527-27-1 Faculty of Human Sciences Mid Sweden University, 85170 Sundsvall Phone: +46 (0)10 142 80 00 Mid Sweden University Doctoral Thesis 270, 2017 For Iris, Martin, and Thomas The stars on my twig Acknowledgements My thesis project has been a bold endeavor and an adventurous journey that lasted far longer than I originally anticipated, so I am really pleased to have completed it. I am glad that, though life intervened on numerous occasions and my circumstances were often foreboding, I continued writing. I am sure I learned a lot about the world and myself that I would not have otherwise. Over time, many people contributed in different ways to my work and I am happy I have encountered them all. Back in school, via the poems of Kavafis, Karyotakis, Seferis, Elytis, and the ancient lyrics, my Greek teacher Christos Foundos showed me the way to the pleasures of poetry. At Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Prof. Ekaterini Georgoudaki handed me the seeds to this thesis on a pink post-it note, empowering me to believe that I could achieve beyond my gender and class limitations. -

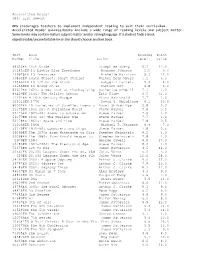

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Test List Report OHS encourages teachers to implement independent reading to suit their curriculum. Accelerated Reader quizzes/books include a wide range of reading levels and subject matter. Some books may contain mature subject matter and/or strong language. If a student finds a book objectionable/uncomfortable he or she should choose another book. Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 68630EN 10th Grade Joseph Weisberg 5.7 11.0 101453EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Maureen Johnson 5.0 9.0 136675EN 13 Treasures Michelle Harrison 5.3 11.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 135667EN 16 1/2 On the Block Babygirl Daniels 5.3 4.0 135668EN 16 Going on 21 Darrien Lee 4.8 6.0 53617EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 86429EN 1634: The Galileo Affair Eric Flint 6.5 31.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 7.7 1.0 104010EN 1776 David G. McCulloug 9.1 20.0 80002EN 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems o Naomi Shihab Nye 5.8 2.0 53175EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 53176EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Steve Parker 7.9 1.0 53177EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Steve Parker 7.7 1.0 53178EN 1960s: Space and Time Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 130068EN 1968 Michael T. Kaufman 9.9 7.0 53179EN 1970-90: Computers and Chips Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 36099EN The 1970s from Watergate to Disc Stephen Feinstein 8.2 1.0 36098EN The 1980s from Ronald Reagan to Stephen Feinstein 7.8 1.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Ad Jules Verne 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

Selected Poetry of Nikki Giovanni

SELECTED POETRY OF NIKKI GIOVANNI: A BURKEIAN ANALYSIS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas Estate University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS 37 Carolyn Tobola, B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1973 Tobola, Carolyn, Selected Poetry of Nikki Giovanni; A Burkeian Analysis. Master of Arts (Speech and Drama), August, 1973> 96 pp., bibliography, b-7 titles. In this study, Kenneth Burke's methods of dramatistic analysis is applied to the selected poetry of Nikki Giovanni, a Black contemporary female poet. The procedure, analysis of poetry for symbolic action, is a functional approach which focuses on the poetic language, Agency. The thesis, divided into four chapters, concentrates on discovery of the Purpose, a Black female motive, for the Act, Giovanni's poetry, in the Scene, contemporary Black America. Chapter I is an overview of Kenneth Burke and his drama- tistic method of analysis. The chapter includes an explana- tion of Burkeian terms pertinent to this study and a list of the nine poems which were categorically selected for this study. Also included in the chapter is a discussion of six procedural steps for poetic analysis. The final three steps are the most important in the procedure: "pun analysis," "rhetoric of rebirth," and "archytypal structure." Chapter II describes the Scene encompassing the Act. The circum- ference of the Scene is narrowed to include the following three areas: political and social, artistic, and familial and personal in order to determine the factors influencing Giovanni's Act. A historical account of the Civil Rights Movement describes "the social and political scene. -

1 JAMES OTTO Just Got Started Lovin' You 2 TRACE

TOP100 OF 2008 1 JAMES OTTO Just Got Started Lovin' You (Warner Bros.) 51 GEORGE STRAIT How 'Bout Them Cowgirls (MCA) 2 TRACE ADKINS You're Gonna Miss This (Capitol) 52 BROOKS & DUNN God Must Be Busy (Arista) 3 RODNEY ATKINS Cleaning This Gun (Come...) (Curb) 53 BUCKY COVINGTON It's Good To Be Us (Lyric Street) 4 CHRIS CAGLE What Kinda Gone (Capitol) 54 CLAY WALKER Fall (Curb) 5 GEORGE STRAIT I Saw God Today (MCA) 55 HEIDI NEWFIELD Johnny And June (Curb) 6 ALAN JACKSON Small Town Southern Man (Arista) 56 JOSH TURNER f/ T . Y E A R W O O D Another Try (MCA) 7 BRAD PAISLEY Letter To Me (Arista) 57 JASON MICHAEL CARROLL Livin' Our Love Song (Arista) 8 BLAKE SHELTON Home (Warner Bros.) 58 CARRIE UNDERWOOD So Small (19/Arista) 9 BRAD PAISLEY I'm Still A Guy (Arista) 59 CHUCK WICKS All I Ever Wanted (RCA) 10 PHIL VASSAR Love Is A Beautiful Thing (Universal South) 60 GARTH BROOKS More Than A Memory (Pearl/Big Machine) 11 GARY ALLAN Watching Airplanes (MCA) 61 TIM MCGRAW Let It Go (Curb) 12 TAYLOR SWIFT Our Song (Big Machine) 62 BUCKY COVINGTON I'll Walk (Lyric Street) 13 LADY ANTEBELLUM Love Don't Live Here (Capitol) 63 CRAIG MORGAN Love Remembers (BNA) 14 KEITH ANDERSON I Still Miss You (Columbia) 64 JAKE OWEN Something About A Woman (RCA) 15 KENNY CHESNEY Don't Blink (BNA) 65 GARY ALLAN Learning How To Bend (MCA) 16 CARRIE UNDERWOOD All-American Girl (19/Arista) 66 JEWEL Stronger Woman (Valory) 17 ALAN JACKSON Good Time (Arista) 67 ZAC BROWN BAND Chicken Fried (Atlantic/Home Grown/BPP) 18 MONTGOMERY GENTRY Back When I Knew It All (Columbia) 68 JAMEY JOHNSON In Color (Mercury) 19 RASCAL FLATTS Winner At A Losing Game (Lyric Street) 69 MONTGOMERY GENTRY Roll With Me (Columbia) 20 JIMMY WAYNE Do You Believe Me Now (Valory) 70 TOBY KEITH Get My Drink On (Show Dog) 21 DARIUS RUCKER Don't Think I Don't Think.. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Appalachian Studies Bibliography Cumulation 2013-June 2016 ______

Appalachian Studies Bibliography Cumulation 2013-June 2016 _____________________ CONTENTS Agriculture and Land Use ................................................................................................................3 Appalachian Studies.........................................................................................................................8 Archaeology and Physical Anthropology ......................................................................................14 Architecture, Historic Buildings, Historic Sites ............................................................................18 Arts and Crafts ..............................................................................................................................21 Biography .......................................................................................................................................27 Civil War, Military.........................................................................................................................29 Coal, Industry, Labor, Railroads, Transportation ..........................................................................37 Description and Travel, Recreation and Sports .............................................................................63 Economic Conditions, Economic Development, Economic Policy, Poverty ................................71 Education .......................................................................................................................................82 -

Country 2020 to 2006

Mediabase Charts Country 2020 Published (U.S.) ‐‐ Currents & Recurrents January 2020 through December, 2020 Rank Artist Title 1 MORGAN WALLEN Chasin' You 2 GABBY BARRETT I Hope f/Charlie Puth 3 BLAKE SHELTON Nobody But You w/Gwen Stefani 4 MAREN MORRIS The Bones 5 TRAVIS DENNING After A Few 6 LUKE COMBS Does To Me f/Eric Church 7 MADDIE & TAE Die From A Broken Heart 8 SAM HUNT Kinfolks 9 THOMAS RHETT Beer Can't Fix f/Jon Pardi 10 JAKE OWEN Homemade 11 SAM HUNT Hard To Forget 12 LUKE BRYAN One Margarita 13 CARLY PEARCE & LEE BRICE I Hope You're Happy Now 14 CHRIS JANSON Done 15 LEE BRICE One Of Them Girls 16 JUSTIN MOORE Why We Drink 17 JAMESON RODGERS Some Girls 18 LUKE COMBS Even Though I'm Leaving 19 MIRANDA LAMBERT Bluebird 20 JASON ALDEAN Got What I Got 21 OLD DOMINION One Man Band 22 BRETT YOUNG Catch 23 LOCASH One Big Country Song 24 MATT STELL Everywhere But On 25 LUKE COMBS Lovin' On You 26 DUSTIN LYNCH Ridin' Roads 27 SCOTTY MCCREERY In Between 28 HARDY One Beer f/L. Alaina/D. Dawson 29 KANE BROWN Homesick 30 INGRID ANDRESS More Hearts Than Mine 31 KEITH URBAN God Whispered Your Name 32 KANE BROWN Cool Again 33 JORDAN DAVIS Slow Dance In A Parking Lot 34 FLORIDA GEORGIA LINE I Love My Country 35 KENNY CHESNEY Here And Now 36 DAN + SHAY & JUSTIN BIEBER 10,000 Hours 37 THOMAS RHETT Be A Light f/McEntire, Scott.. 38 RUSSELL DICKERSON Love You Like I Used To 39 PARKER MCCOLLUM Pretty Heart 40 JON PARDI Heartache Medication 41 MORGAN WALLEN Whiskey Glasses 42 LUKE BRYAN What She Wants Tonight 43 CHASE RICE Lonely If You Are 44 JIMMIE