Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orazio Costa Regista. Dalla Compagnia Dell’Accademia Al Piccolo Di Roma (1939- 1954)

Orazio Costa regista. Dalla Compagnia dell’Accademia al Piccolo di Roma (1939- 1954). Fonti e documenti dal suo archivio Dipartimento di Storia Antropologia Religioni Arte Spettacolo Dottorato di Ricerca in Musica e Spettacolo XXXII ciclo – Studi di Teatro Massimo Giardino Tutor Co-tutor Roberto Ciancarelli Stefano Geraci Orazio Costa regista. Dalla Compagnia dell’Accademia al Piccolo di Roma (1939- 1954). Fonti e documenti dal suo archivio Dipartimento di Storia Antropologia Religioni Arte Spettacolo Dottorato di Ricerca in Musica e Spettacolo XXXII ciclo – Studi di Teatro Massimo Giardino Matricola 1740690 Tutor Co-tutor Roberto Ciancarelli Stefano Geraci A.A. 2018-2019 INDICE PRESENTAZIONE 4 RICOGNIZIONE DEGLI STUDI E DELLE RICERCHE SU ORAZIO COSTA 10 CAPITOLO PRIMO. UN REGISTA PRIMA DELLA REGIA 1.1. Un’“innata” vocazione teatrale 12 1.2. La Scuola di Recitazione “Eleonora Duse” 15 1.3. L’educazione per un teatro possibile 21 1.4. Tra una scuola e l’altra 32 CAPITOLO SECONDO. LE PRIME REGIE COSTIANE 2.1. L’Accademia d’Arte Drammatica 36 2.2. Le assistenze alla regia 40 2.3. L’apprendistato con Copeau 47 2.4. La Compagnia dell’Accademia 54 CAPITOLO TERZO. REGISTA DI COMPAGNIA 3.1. La prima regia senza D’Amico 70 3.2. La seconda Compagnia dell’Accademia 73 3.3. Le regie ibseniane 77 3.4. I semi del metodo mimico 81 3.5. La collaborazione con la Compagnia Pagnani-Ninchi 84 3.6. Le ultime collaborazioni come regista di compagnia 85 CAPITOLO QUARTO. LA COMPAGNIA DEL TEATRO QUIRINO 4.1. La formazione della Compagnia 93 4.2. -

Diego De Moxena, El Liber Sine Nomine De Petrarca Y El Concilio De Constanza

Quaderns d’Italià 20, 2015 59-87 Diego de Moxena, el Liber sine nomine de Petrarca y el concilio de Constanza Íñigo Ruiz Arzalluz Universidad del País Vasco / Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea [email protected] Resumen Diego de Moxena, franciscano probablemente castellano activo en el concilio de Cons- tanza, escribe el 9 de julio de 1415 a Fernando I de Aragón una carta en la que le insta a sumarse al concilio y reconsiderar su apoyo a Benedicto XIII. El escrito de Moxena revela un uso del Liber sine nomine de Petrarca —advertido ya por Isaac Vázquez Janeiro— que resulta especialmente llamativo: además de tratarse de un testimonio muy temprano en la historia del petrarquismo hispano, el conjunto formado por el prefacio y las dos primeras epístolas del Liber sine nomine no viene utilizado como un simple repertorio de sentencias, sino que constituye el modelo sobre el que se construye la carta en la que, por lo demás y extraordinariamente, en ningún momento se menciona el nombre de Petrarca. De otro lado, se ponen en cuestión algunas de las fuentes postuladas por Vázquez Janeiro y se ofrece una nueva edición de la carta de fray Diego. Palabras clave: Diego de Moxena; Petrarca; Liber sine nomine; concilio de Constanza; petrarquismo hispano; Dietrich von Münster. Abstract. Diego de Moxena, the Liber sine nomine and the Council of Constance On the 9th of July in 1415, Diego de Moxena, very likely a Castilian Franciscan active in the Council of Constance, wrote a letter to Ferdinand I of Aragon in which he urged him to attend the Council and to reconsider his support to Benedict XIII. -

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar ______

THE TRAGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR ___________________________ by Dan Gurskis based on the play by William Shakespeare THE TRAGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR FADE IN: A STATUE OF JULIUS CAESAR in a modern military dress uniform. Then, after a moment, it begins. First, a trickle. Then, a stream. Then, a rush. The statue is bleeding from the chest, the neck, the arms, the abdomen, the hands — dozens of wounds. DISSOLVE TO: EXT. HILLY COUNTRYSIDE — DAY Late winter. The ground is mottled with patches of snow and ice. BURNED IN are the words: "Kosovo, soon after the unrest." Somewhere in the distance, an open-topped Jeep bounces along a rutted, twisting road. INT. OPEN-TOPPED JEEP — MOVING FLAVIUS and MARULLUS, two military officers in uniform, occupy the front passenger's seat and the rear seat, respectively. An ENLISTED MAN is behind the wheel. The three ride in silence for a moment, huddled against the cold, wind whipping through their hair. There is a casual almost careless air to the men. If they do not feel invincible, they feel at the very least unconcerned. Even the machine gun mounted on the rear of the Jeep goes unattended. Just then, automatic sniperfire RINGS OUT of the surrounding woods. The windshield SHATTERS. The driver's forehead explodes in a spray of blood and bone. He slumps over the steering wheel, pulling it hard to the side. ANGLE ON THE JEEP swerving off the road, flipping down an embankment. All three men are thrown from the Jeep, which comes to rest on its side. The driver, clearly dead, lies wide-eyed in a ditch. -

External Projection of a “Minority Language”: Comparing Basque and Catalan with Spanish

東京外国語大学論集 第 100 号(2020) TOKYO UNIVERSITY OF FOREIGN STUDIES, AREA AND CULTURE STUDIES 100 (2020) 43 External Projection of a “Minority Language”: Comparing Basque and Catalan with Spanish 「少数言語」の対外普及 ̶̶ バスク語とカタルーニャ語 の事例をスペイン語の事例と比較しつつ HAGIO Sho W o r l d L a n g u a g e a n d S o c i e t y E d u c a t i o n C e n t r e , T o k y o U n i v e r s i t y o f F o r e i g n S t u d i e s 萩尾 生 東京外国語大学 世界言語社会教育センター 1. The Historical Background of Language Dissemina on Overseas 2. Theore cal Frameworks 2.1. Implemen ng the Basis of External Diff usion 2.2. Demarca on of “Internal” and “External” 2.3. The Mo ves and Aims of External Projec on of a Language 3. The Case of Spain 3.1. The Overall View of Language Policy in Spain 3.2. The Cervantes Ins tute 3.3. The Ramon Llull Ins tute 3.4. The Etxepare Basque Ins tute 4. Transforma on of Discourse 4.1. The Ra onale for External Projec on and Added Value 4.2. Toward Deterritorializa on and Individualiza on? 5. Hypothe cal Conclusion Keywords: Language spread, language dissemination abroad, minority language, Basque, Catalan, Spanish, linguistic value, linguistic market キーワード:言語普及、言語の対外普及、少数言語、バスク語、カタルーニャ語、スペイン語、言語価値、 言語市場 ᮏ✏䛾ⴭసᶒ䛿ⴭ⪅䛜ᡤᣢ䛧䚸 䜽䝸䜶䜲䝔䜱䝤䞉 䝁䝰䞁䝈⾲♧㻠㻚㻜ᅜ㝿䝷䜲䝉䞁䝇䠄㻯㻯㻙㻮㼅㻕ୗ䛻ᥦ౪䛧䜎䛩䚹 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ja 萩尾 生 Hagio Sho External Projection of a “Minority Language”: Comparing Basque and Catalan with Spanish 「少数言語」 の対外普及 —— バスク語とカタルーニャ語 の 事 例をスペイン語の事例と比較しつつ 44 Abstract This paper explores the value of the external projection of a minority language overseas, taking into account the cases of Basque and Catalan in comparison with Spanish. -

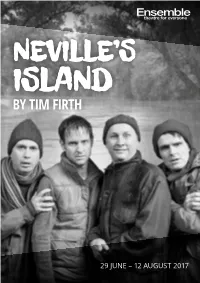

12 AUGUST 2017 “For There Is Nothing Either Good Or Bad, but Thinking Makes It So.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2

29 JUNE – 12 AUGUST 2017 “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2. Ramsey Island, Dargonwater. Friday. June. DIRECTOR ASSISTANT DIRECTOR MARK KILMURRY SHAUN RENNIE CAST CREW ROY DESIGNER ANDREW HANSEN HUGH O’CONNOR NEVILLE LIGHTING DESIGNER DAVID LYNCH BENJAMIN BROCKMAN ANGUS SOUND DESIGNER DARYL WALLIS CRAIG REUCASSEL DRAMATURGY GORDON JANE FITZGERALD CHRIS TAYLOR STAGE MANAGER STEPHANIE LINDWALL WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO: ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER SLADE BLANCH / DANI IRONSIDE Jacqui Dark as Denise, WARDROBE COORDINATOR Shaun Rennie as DJ Kirk, ALANA CANCERI Vocal Coach Natasha McNamara, MAKEUP Kanen Breen & Kyle Rowling PEGGY CARTER First performed by Stephen Joseph Theatre, Scarborough in May 1992. NEVILLE’S ISLAND @Tim Firth Copyright agent: Alan Brodie Representation Ltd. www.alanbrodie.com RUNNING TIME APPROX 2 HOURS 10 MINUTES INCLUDING INTERVAL 02 9929 0644 • ensemble.com.au TIM FIRTH – PLAYWRIGHT Tim’s recent theatre credits include the musicals: THE GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination), THIS IS MY FAMILY (UK Theatre Award Best Musical), OUR HOUSE (West End, Olivier Award Best Musical) and THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY. His plays include NEVILLE’S ISLAND (West End, Olivier Nomination), CALENDAR GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination) SIGN OF THE TIMES (West End) and THE SAFARI PARTY. Tim’s film credits include CALENDAR GIRLS, BLACKBALL, KINKY BOOTS and THE WEDDING VIDEO. His work for television includes MONEY FOR NOTHING (Writer’s Guild Award), THE ROTTENTROLLS (BAFTA Award), CRUISE OF THE GODS, THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY and PRESTON FRONT (Writer’s Guild “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Award; British Comedy Award, RTS Award, BAFTA nomination). -

The Long Take

ADVANCE INFORMATION LONGLISTED FOR MAN BOOKER PRIZE 2018 THE LONG TAKE Robin Robertson 9781509846887 POETRY Picador ǀ Rs 699 ǀ 256pp ǀ Hardback ǀ S Format Feb 22, 2018 A powerful work from award-winning poet Robin Robertson which follows a D-Day veteran as he goes in search of freedom and repair in post-war America. Winner of The Roehampton Poetry Prize 2018 A noir narrative written with the intensity and power of poetry, The Long Take is one of the most remarkable - and unclassifiable - books of recent years. Walker is a D-Day veteran with post-traumatic stress disorder; he can't return home to rural Nova Scotia, and looks instead to the city for freedom, anonymity and repair. As he moves from New York to Los Angeles and San Francisco we witness a crucial period of fracture in American history, one that also allowed film noir to flourish. The Dream had gone sour but - as those dark, classic movies made clear - the country needed outsiders to study and dramatise its new anxieties. While Walker tries to piece his life together, America is beginning to come apart: deeply paranoid, doubting its own certainties, riven by social and racial division, spiralling corruption and the collapse of the inner cities. The Long Take is about a good man, brutalised by war, haunted by violence and apparently doomed to return to it - yet resolved to find kindness again, in the world and in himself. Watching beauty and disintegration through the lens of the film camera and the eye of the poet, Robin Robertson's The Long Take is a work of thrilling originality. -

Grade 10 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene Ii

Grade 10 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene ii by William Shakespeare This grade 10 mini-assessment is based on an excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene ii by William Shakespeare and a video of the scene. This text is considered to be worthy of students’ time to read and also meets the expectations for text complexity at grade 10. Assessments aligned to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) will employ quality, complex texts such as this one. Questions aligned to the CCSS should be worthy of students’ time to answer and therefore do not focus on minor points of the text. Questions also may address several standards within the same question because complex texts tend to yield rich assessment questions that call for deep analysis. In this mini- assessment there are seven selected-response questions and one paper/pencil equivalent of technology enhanced items that address the Reading Standards listed below. Additionally, there is an optional writing prompt, which is aligned to both the Reading Standards for Literature and the Writing Standards. We encourage educators to give students the time that they need to read closely and write to the source. While we know that it is helpful to have students complete the mini-assessment in one class period, we encourage educators to allow additional time as necessary. Note for teachers of English Language Learners (ELLs): This assessment is designed to measure students’ ability to read and write in English. Therefore, educators will not see the level of scaffolding typically used in instructional materials to support ELLs—these would interfere with the ability to understand their mastery of these skills. -

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 Through 2009

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 through 2009 COMPILED BY MOLLY BLA C K VERENE TABLE OF CON T EN T S PART I. Books A. Monographs . .84 B. Collected Volumes . 98 C. Dissertations and Theses . 111 D. Journals......................................116 PART II. Essays A. Articles, Chapters, et cetera . 120 B. Entries in Reference Works . 177 C. Reviews and Abstracts of Works in Other Languages ..180 PART III. Translations A. English Translations ............................186 B. Reviews of Translations in Other Languages.........192 PART IV. Citations...................................195 APPENDIX. Bibliographies . .302 83 84 NEW VICO STUDIE S 27 (2009) PART I. BOOKS A. Monographs Adams, Henry Packwood. The Life and Writings of Giambattista Vico. London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reprinted New York: Russell and Russell, 1970. REV I EWS : Gianturco, Elio. Italica 13 (1936): 132. Jessop, T. E. Philosophy 11 (1936): 216–18. Albano, Maeve Edith. Vico and Providence. Emory Vico Studies no. 1. Series ed. D. P. Verene. New York: Peter Lang, 1986. REV I EWS : Daniel, Stephen H. The Eighteenth Century: A Current Bibliography, n.s. 12 (1986): 148–49. Munzel, G. F. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 173–75. Simon, L. Canadian Philosophical Reviews 8 (1988): 335–37. Avis, Paul. The Foundations of Modern Historical Thought: From Machiavelli to Vico. Beckenham (London): Croom Helm, 1986. REV I EWS : Goldie, M. History 72 (1987): 84–85. Haddock, Bruce A. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 185–86. Bedani, Gino L. C. Vico Revisited: Orthodoxy, Naturalism and Science in the ‘Scienza nuova.’ Oxford: Berg, 1989. REV I EWS : Costa, Gustavo. New Vico Studies 8 (1990): 90–92. -

E R a S M U S Boekh An

75 Y E A R S ERASMUS BOEKHANDEL PARIS AMSTERDAM 75 75 years E R A S M U S S BOEKHANDEL AMSTERDAM- 75 PARIS years ERASMUS BOEKHANDEL PARIS AMSTERDAM 75 YEARS ERASMUS BOEKHANDEL AMSTERDAM-PARIS Sytze van der Veen 2009 2 1 Table of contents 5 Preface 7 Early history 8 The art of the book and art books 10 The Book of Books 13 Night train to Amsterdam 14 Taking risks 15 Book paradise 17 Tricks of the trade 19 Erasmus under the occupation 25 The other side of the mountains 26 Resurrection 28 A man with vision 31 Widening the horizon 32 Of bartering and friendly turns 37 A passion for collecting 39 Steady growth 42 Bookshop and antiquarian department 47 Twilight of the patriarch 52 New blood 54 Changing times 57 Renewal 61 Erasmus and Hermes 65 Books in transit 69 Librairie Erasmus in Paris 73 Erasmus at present 75 Modern business management 78 Tenders, shelf-ready delivery and e-books 80 New Title Service 81 Standing Order Department 83 Approval Plans 86 www.erasmusbooks.nl and www.erasmus.fr 90 Festina lente 92 Afterword 96 List of abbreviations used for illustrations 96 Colophon 2 3 Preface This book is offered to you by Erasmus Boekhandel to mark its 75th anniversary. It outlines the history of our company and shows how present trends are based on past achievements. On the occasion of this jubilee we wish to thank our library clients and business partners in the publishing world for their continued support and the excellent relations we have maintained with them over the years. -

Become a Member

Dante Alighieri Society of Pueblo New and Renewal Application for Calendar Year 2021 The Dante Alighieri Society was formed in Italy in July 1889 to “promote the study of the Italian language and culture throughout the world…independent of political ideologies, national, or ethnic origin or religious beliefs. The Society is the free association of people -not just Italians- but all people everywhere who are united by their love for the Italian language and culture and the spirit of universal humanism that these represent.” The Society was named after Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), a pre-Renaissance poet from Florence, Italy. Dante, the author of The Divine Comedy, is considered the father of the Italian language. The Dante Alighieri Society of Pueblo, Colorado was founded by Father Christopher Tomatis on October 24, 1977 and ratified by the Dante Alighieri Society in Rome, Italy on December 3, 1977. Mission Statement The mission of the Dante Alighieri Society of Pueblo, Colorado is to promote and preserve the Italian language, culture, and customs in Pueblo and the Southern Colorado Region. ° Scholarships will be awarded to selected senior high students who have completed two or more years of Italian language classes in the Pueblo area high schools. ° Cultural and social activities will be sponsored to enhance the Italian-American community. Activities of the Society Cultural Dinner Meetings Regional Italian Dinner (November) Carnevale Dinner Dance (February) Annual Christmas Party (December) Scholarship Awards (May) Artistic Performances and Speakers Dante Summer Festa (August) Sister City Festival Participation Italian Conversation Classes Italian Language Scholarships To join the Dante Alighieri Society of Pueblo or to renew your membership, please detach and mail with your check. -

A British Reflection: the Relationship Between Dante's Comedy and The

A British Reflection: the Relationship between Dante’s Comedy and the Italian Fascist Movement and Regime during the 1920s and 1930s with references to the Risorgimento. Keon Esky A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. University of Sydney 2016 KEON ESKY Fig. 1 Raffaello Sanzio, ‘La Disputa’ (detail) 1510-11, Fresco - Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican. KEON ESKY ii I dedicate this thesis to my late father who would have wanted me to embark on such a journey, and to my partner who with patience and love has never stopped believing that I could do it. KEON ESKY iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis owes a debt of gratitude to many people in many different countries, and indeed continents. They have all contributed in various measures to the completion of this endeavour. However, this study is deeply indebted first and foremost to my supervisor Dr. Francesco Borghesi. Without his assistance throughout these many years, this thesis would not have been possible. For his support, patience, motivation, and vast knowledge I shall be forever thankful. He truly was my Virgil. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the whole Department of Italian Studies at the University of Sydney, who have patiently worked with me and assisted me when I needed it. My sincere thanks go to Dr. Rubino and the rest of the committees that in the years have formed the panel for the Annual Reviews for their insightful comments and encouragement, but equally for their firm questioning, which helped me widening the scope of my research and accept other perspectives. -

«Vero Omnia Consonant». Ideologia E Politica Di Petrarca Nel Liber Sine Nomine

Paolo Viti «Vero omnia consonant». Ideologia e politica di Petrarca nel Liber sine nomine Parole chiave: Petrarca, 'Liber sine nomine', Cola di Rienzo, Curia avignonese, Denuncia Keywords: Petrarca, 'Liber sine nomine', Cola di Rienzo, Avignon Curia, Condemnation Contenuto in: Le carte e i discepoli. Studi in onore di Claudio Griggio Curatori: Fabiana di Brazzà, Ilvano Caliaro, Roberto Norbedo, Renzo Rabboni e Matteo Venier Editore: Forum Luogo di pubblicazione: Udine Anno di pubblicazione: 2016 Collana: Tracce. Itinerari di ricerca/Area umanistica e della formazione ISBN: 978-88-8420-917-7 ISBN: 978-88-3283-054-5 (versione digitale) Pagine: 67-98 DOI: 10.4424/978-88-8420-917-7-07 Per citare: Paolo Viti, ««Vero omnia consonant». Ideologia e politica di Petrarca nel Liber sine nomine», in Fabiana di Brazzà, Ilvano Caliaro, Roberto Norbedo, Renzo Rabboni e Matteo Venier (a cura di), Le carte e i discepoli. Studi in onore di Claudio Griggio, Udine, Forum, 2016, pp. 67-98 Url: http://forumeditrice.it/percorsi/lingua-e-letteratura/tracce/le-carte-e-i-discepoli/vero-omnia-consonant-ideologia-e- politica-di FARE srl con socio unico Università di Udine Forum Editrice Universitaria Udinese via Larga, 38 - 33100 Udine Tel. 0432 26001 / Fax 0432 296756 / forumeditrice.it «VERO OMNIA CONSONANT». IDEOLOGIA E POLITICA DI PETRARCA NEL LIBER SINE NOMINE Paolo Viti Pur non potendo isolare parti troppo limitate all’interno dell’intera produzione petrarchesca, mi sembra utile selezionare alcuni passi contenuti nel Liber sine nomine – collezione di lettere in stretta corrispondenza con le Familiares1 – so- prattutto in rapporto all’altezza cronologica in cui tali lettere furono composte, fra il 1342 e il 1359, ma con alcuni nuclei ben precisi: nel 1342 la I a Philippe de Cabassole, nel 1347 la II e la III a Cola di Rienzo, nel 1357 e nel 1358 le ultime tre (XVII-XIX) a Francesco Nelli.