Julius Caesar © 2015 American Shakespeare Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar ______

THE TRAGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR ___________________________ by Dan Gurskis based on the play by William Shakespeare THE TRAGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR FADE IN: A STATUE OF JULIUS CAESAR in a modern military dress uniform. Then, after a moment, it begins. First, a trickle. Then, a stream. Then, a rush. The statue is bleeding from the chest, the neck, the arms, the abdomen, the hands — dozens of wounds. DISSOLVE TO: EXT. HILLY COUNTRYSIDE — DAY Late winter. The ground is mottled with patches of snow and ice. BURNED IN are the words: "Kosovo, soon after the unrest." Somewhere in the distance, an open-topped Jeep bounces along a rutted, twisting road. INT. OPEN-TOPPED JEEP — MOVING FLAVIUS and MARULLUS, two military officers in uniform, occupy the front passenger's seat and the rear seat, respectively. An ENLISTED MAN is behind the wheel. The three ride in silence for a moment, huddled against the cold, wind whipping through their hair. There is a casual almost careless air to the men. If they do not feel invincible, they feel at the very least unconcerned. Even the machine gun mounted on the rear of the Jeep goes unattended. Just then, automatic sniperfire RINGS OUT of the surrounding woods. The windshield SHATTERS. The driver's forehead explodes in a spray of blood and bone. He slumps over the steering wheel, pulling it hard to the side. ANGLE ON THE JEEP swerving off the road, flipping down an embankment. All three men are thrown from the Jeep, which comes to rest on its side. The driver, clearly dead, lies wide-eyed in a ditch. -

12 AUGUST 2017 “For There Is Nothing Either Good Or Bad, but Thinking Makes It So.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2

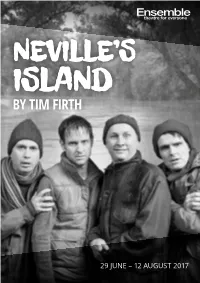

29 JUNE – 12 AUGUST 2017 “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2. Ramsey Island, Dargonwater. Friday. June. DIRECTOR ASSISTANT DIRECTOR MARK KILMURRY SHAUN RENNIE CAST CREW ROY DESIGNER ANDREW HANSEN HUGH O’CONNOR NEVILLE LIGHTING DESIGNER DAVID LYNCH BENJAMIN BROCKMAN ANGUS SOUND DESIGNER DARYL WALLIS CRAIG REUCASSEL DRAMATURGY GORDON JANE FITZGERALD CHRIS TAYLOR STAGE MANAGER STEPHANIE LINDWALL WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO: ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER SLADE BLANCH / DANI IRONSIDE Jacqui Dark as Denise, WARDROBE COORDINATOR Shaun Rennie as DJ Kirk, ALANA CANCERI Vocal Coach Natasha McNamara, MAKEUP Kanen Breen & Kyle Rowling PEGGY CARTER First performed by Stephen Joseph Theatre, Scarborough in May 1992. NEVILLE’S ISLAND @Tim Firth Copyright agent: Alan Brodie Representation Ltd. www.alanbrodie.com RUNNING TIME APPROX 2 HOURS 10 MINUTES INCLUDING INTERVAL 02 9929 0644 • ensemble.com.au TIM FIRTH – PLAYWRIGHT Tim’s recent theatre credits include the musicals: THE GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination), THIS IS MY FAMILY (UK Theatre Award Best Musical), OUR HOUSE (West End, Olivier Award Best Musical) and THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY. His plays include NEVILLE’S ISLAND (West End, Olivier Nomination), CALENDAR GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination) SIGN OF THE TIMES (West End) and THE SAFARI PARTY. Tim’s film credits include CALENDAR GIRLS, BLACKBALL, KINKY BOOTS and THE WEDDING VIDEO. His work for television includes MONEY FOR NOTHING (Writer’s Guild Award), THE ROTTENTROLLS (BAFTA Award), CRUISE OF THE GODS, THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY and PRESTON FRONT (Writer’s Guild “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Award; British Comedy Award, RTS Award, BAFTA nomination). -

Teacher Resource Pack I, Malvolio

TEACHER RESOURCE PACK I, MALVOLIO WRITTEN & PERFORMED BY TIM CROUCH RESOURCES WRITTEN BY TIM CROUCH unicorntheatre.com timcrouchtheatre.co.uk I, MALVOLIO TEACHER RESOURCES INTRODUCTION Introduction by Tim Crouch I played the part of Malvolio in a production of Twelfth Night many years ago. Even though the audience laughed, for me, it didn’t feel like a comedy. He is a desperately unhappy man – a fortune spent on therapy would only scratch the surface of his troubles. He can’t smile, he can’t express his feelings; he is angry and repressed and deluded and intolerant, driven by hate and a warped sense of self-importance. His psychiatric problems seem curiously modern. Freud would have had a field day with him. So this troubled man is placed in a comedy of love and mistaken identity. Of course, his role in Twelfth Night would have meant something very different to an Elizabethan audience, but this is now – and his meaning has become complicated by our modern understanding of mental illness and madness. On stage in Twelfth Night, I found the audience’s laughter difficult to take. Malvolio suffers the thing we most dread – to be ridiculed when he is at his most vulnerable. He has no resolution, no happy ending, no sense of justice. His last words are about revenge and then he is gone. This, then, felt like the perfect place to start with his story. My play begins where Shakespeare’s play ends. We see Malvolio how he is at the end of Twelfth Night and, in the course of I, Malvolio, he repairs himself to the state we might have seen him in at the beginning. -

Cato, Roman Stoicism, and the American 'Revolution'

Cato, Roman Stoicism, and the American ‘Revolution’ Katherine Harper A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Arts Faculty, University of Sydney. March 27, 2014 For My Parents, To Whom I Owe Everything Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... i Abstract.......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One - ‘Classical Conditioning’: The Classical Tradition in Colonial America ..................... 23 The Usefulness of Knowledge ................................................................................... 24 Grammar Schools and Colleges ................................................................................ 26 General Populace ...................................................................................................... 38 Conclusions ............................................................................................................... 45 Chapter Two - Cato in the Colonies: Joseph Addison’s Cato: A Tragedy .......................................... 47 Joseph Addison’s Cato: A Tragedy .......................................................................... 49 The Universal Appeal of Virtue ........................................................................... -

Grade 10 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene Ii

Grade 10 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene ii by William Shakespeare This grade 10 mini-assessment is based on an excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene ii by William Shakespeare and a video of the scene. This text is considered to be worthy of students’ time to read and also meets the expectations for text complexity at grade 10. Assessments aligned to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) will employ quality, complex texts such as this one. Questions aligned to the CCSS should be worthy of students’ time to answer and therefore do not focus on minor points of the text. Questions also may address several standards within the same question because complex texts tend to yield rich assessment questions that call for deep analysis. In this mini- assessment there are seven selected-response questions and one paper/pencil equivalent of technology enhanced items that address the Reading Standards listed below. Additionally, there is an optional writing prompt, which is aligned to both the Reading Standards for Literature and the Writing Standards. We encourage educators to give students the time that they need to read closely and write to the source. While we know that it is helpful to have students complete the mini-assessment in one class period, we encourage educators to allow additional time as necessary. Note for teachers of English Language Learners (ELLs): This assessment is designed to measure students’ ability to read and write in English. Therefore, educators will not see the level of scaffolding typically used in instructional materials to support ELLs—these would interfere with the ability to understand their mastery of these skills. -

Lamctott Liu/ Which Was Regarded As the Chief Point of Interest, Not Only of This Day’S Excursion, but of the Whole Meeting

38 Thirty-eighth Annual Meeting, Upon the motion of the President, a vote of thanks was offered to Mr. Green, for the diligence with which he had collected his materials, and the manner in which he had thrown light upon the subject of his paper. Mr. Green then read a paper hy Mr. Kerslake, on Gifla,^’ which is printed in Part II. p. 16. Mr. Green expressed his opinion that the derivation of the name was not from the river Yeo, which was a modern name. The meeting then terminated. The morning was delightfully fine, and at 9.30, the carriages being in readiness, a goodly number of Members left Yeovil for lamctott liU/ which was regarded as the chief point of interest, not only of this day’s excursion, but of the whole meeting. After a pleasant drive, passing by Odcombe, the birth-place of Tom Coryate,^ the cortege entered the camp by “ Bedmore Barn,’^ the site of the discovery of the large hoard of Roman coins in 1882, and drew up at (1) belonging to Mr. Charles Trask. The party having assembled on the edge of one of the deep excavations, at the bottom of (2) which the workmen were engaged in quarrying the celebrated Ham-stone,” Mr. Trask was asked to say a few words about the quarries. He said that the marl stone of the upper Lias was found plentifully along the level land within half a mile of the foot of the hill, on the western side. Above this were the Oolitic — : is . Leland says “ Hamden hill a specula, ther to view a greate piece of the country therabout The notable quarre of stone is even therby at Hamden out of the which hath been taken stones for al the goodly buildings therabout in al quarters.” paper, part ii. -

Study Guide 2016-2017

Study Guide 2016-2017 by William Shakespeare Standards Theatre English Language Arts Social Studies TH.68.C.2.4: Defend personal responses. LAFS.68.RH.1.2: Determine central ideas. SS.912.H.1.5: Examine social issues. TH.68.C.3.1: Discuss design elements. LAFS.910.L.3.4: Determine unknown words. TH.68.H.1.5: Describe personal responses. LAFS.910.L.3.5: Demonstrate figurative language. TH.912.S.1.8: Use research to extract clues. LAFS.1112.SL.1.1: Initiate collaborative discussions. TH.912.S.2.9: Research artistic choices. TH.912.H.1.4: Interpret through historical lenses. Content Advisory: Antony and Cleopatra is a political drama fueled by intimate relationships. There are battle scenes. If it were a movie, Antony and Cleopatra would be rated “PG-13.” !1 Antony and Cleopatra Table of Contents Introduction p. 3 Enjoying Live Theater p. 3 About the Play p. 6 Plot Summary p. 6 Meet the Characters p. 7 Meet the Playwright p. 8 Historical Context p. 11 Elizabethan Theater p. 11 Activities p. 12 Themes and Discussion p. 17 Bibliography p. 17 !2 Antony and Cleopatra An Introduction Educators: Thank you for taking the time out of your very busy schedule to bring the joy of theatre arts to your classroom. We at Orlando Shakes are well aware of the demands on your time and it is our goal to offer you supplemental information to compliment your curriculum with ease and expediency. What’s New? Lots! First, let me take a moment to introduce our new Children’s Series Coordinator, Brandon Yagel. -

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis Romanische Literaturen der Welt Herausgegeben von Ottmar Ette Band 61 Petrarch and Boccaccio The Unity of Knowledge in the Pre-modern World Edited by Igor Candido An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. The Open Access book is available at www.degruyter.com. ISBN 978-3-11-042514-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041930-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041958-0 ISSN 0178-7489 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 license. For more information, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Igor Candido, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Konvertus, Haarlem Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Dedicated to Ronald Witt (1932–2017) Contents Acknowledgments IX Igor Candido Introduction 1 H. Wayne Storey The -

Bacon-Shakespeare Timeline

Bacon-Shakespeare Timeline Chart of the dates of the Francis Bacon and William Shakespeare literary works together with key dates in Bacon’s life. Author: Peter Dawkins The following chart gives the dates of composition and publication of the Francis Bacon and William Shakespeare literary works together with key dates in Francis Bacon’s life. The dates are given as accurately as possible, although some of these (such as for the writing of the Shakespeare plays) can only be approximate. Key to the Chart: Bacon Ph = Philosophical & Literary Ph# = Great Instauration, # referring to which Part of the G.I. the writings belong. Po* = Poetic L = Legal O = Other Shakespeare Po† = Poetic underlined = publications during Bacon’s lifetime Blue text = other important events Dates of Francis Bacon’s Life and Works and the Shakespeare Works 22 Jan. 1561 Birth of Francis Bacon (FB) 25 Jan. 1561 Baptism of Francis Bacon 1572-4 Supernova in Cassiopeia April 1573-1575 FB student at Trinity College, Cambridge – left Dec 1575 July 1575 The Kenilworth Entertainment Aug. 1575 The Woodstock Tournament 27 June 1576 FB admitted de societate magistrorum at Gray’s Inn 25 Sept.1576 FB departs for Paris, France, as an attaché to Sir Amyas Paulet, the new English ambassador to the French Court – besides studying French culture, politics and law, works as an intelligencer Dec 1576 FB moves with the embassy and French Court to Blois March 1577 FB moves with the embassy and French Court to Tours, then Poitiers Aug 1577 FB moves with the embassy and French Court to Poitiers Aug-Sept 1577 FB travels to England to deliver a secret message to the Queen Oct. -

The Public and Private Life of Lord Chancellor Eldon

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com ThepublicandprivatelifeofLordChancellorEldon HoraceTwiss > JHEMPMEyER ,"Bequest of oAlice Meyer 'Buck, 1882-1979 Stanford University libraries > I I I Mk ••• ."jJ-Jf* y,j\X:L ij.T .".[.DDF ""> ». ; v -,- ut y ftlftP * ii Willi i)\l I; ^ • **.*> H«>>« FR'iM •• ••.!;.!' »f. - i-: r w i v ^ &P v ii:-:) l:. Ill I the PUBLIC AND PRIVATE LIFE or LORD CHANCELLOR ELDON, WITH SELECTIONS FROM HIS CORRESPONDENCE. HORACE TWISS, ESQ. one op hkr Majesty's counsel. IN THREE VOLUMES. VOL. III. Ingens ara fuit, juxtaquc veterrima laurus Incumbcns ane, atque umbra complexa Penates." ViRG. JEn. lib. ii. 513, 514. Hard by, an aged laurel stood, and stretch'd Its arms o'er the great altar, in its shade Sheltering the household gods." LONDON: JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET. 1844. w3 London : Printed by A. Spottiswoode, New- Street- Square. CONTENTS THE THIRD VOLUME CHAPTER L. 1827. Letter from Lord Eldon to Lady F. J. Bankes. — Mr. Brougham's Silk Gown. — Game Laws. — Unitarian Marriages. — Death and Character of Mr. Canning. — Formation of Lord Goderich's Ministry. — Duke of Wellington's Acceptance of the Command of the Army : Letters of the Duke, of Lord Goderich, of the King, and of Lord Eldon. — Letters of Lord Eldon to Lord Stowell and to Lady Eliza beth Repton. — Close of the Anecdote- Book : remaining Anec dotes ------- Page 1 CHAPTER LI. 1828. Dissolution of Lord Goderich's Ministry, and Formation of the Duke of Wellington's : Letters of Lord Eldon to Lady F. -

Arthur Annesley, Margaret Cavendish, and Neo-Latin History

The Review of English Studies, New Series, Vol. 69, No. 292, 855–873 doi: 10.1093/res/hgy069 Advance Access Publication Date: 22 August 2018 Arthur Annesley, Margaret Cavendish, and Neo-Latin History Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/res/article-abstract/69/292/855/5078044 by guest on 13 November 2018 Justin Begley ABSTRACT This article explores a hitherto unstudied copy of De vita [...] Guilielmi ducis Novo- Castrensis (1668)—a Latin translation of The Life of William Cavendish (1667) by Margaret Cavendish (1623?–1673)—that Arthur Annesley (1614–1686), the First Earl of Anglesey, has heavily annotated. While Annesley owned the largest private li- brary in seventeenth-century Britain, his copy of De vita is by far the most densely glossed of his identifiable books, with no fewer than sixty-one Latin and Greek annota- tions, not to mention numerous corrections and non-verbal markers. By studying Annesley’s careful treatment of De vita, this essay makes an intervention into the bur- geoning fields of reading and library history along with neo-Latin studies. I propose that Annesley filled the margins of De vita with quotations from Latin poets, scholars, philosophers, and historians—rather than his personal views—in a bid to form a polit- ically impartial outlook on the British Civil Wars that was attuned to broader historical or even mythological trends. I. INTRODUCTION On 18 March 1668, the renowned diarist, Samuel Pepys (1633–1703), recorded that he had stayed ‘home reading the ridiculous history of my Lord Newcastle wrote by his wife, which shows her to be a mad, conceited, ridiculous woman, and he an asse to suffer [her] to write what she writes to him and of him’.1 Pepys’s evaluation of Margaret Cavendish (1623?–1673) and her 1667 The Life of William Cavendishe—an account of the deeds of her husband, William Cavendish (1592–1676), in the British Civil Wars—has fuelled the view that contemporaries either scorned or neglected her books.2 Yet, in spite of Pepys’s assessment, Cavendish’s history went through nu- merous editions over the years. -

Julius+Caesar+Play+Critique.Pdf

"Julius Caesar." Shakespearean Criticism. Ed. Michael L. LaBlanc. Vol. 74. Detroit: Gale, 2003. Literature Resources from Gale. Gale. Cape Cod Regional Technical High School. 4 Jan. 2011 <http://go.galegroup.com/ps/start.do?p=LitRG&u=mlin_s_ccreg>. Title: Julius Caesar Source: Shakespearean Criticism. Ed. Michael L. LaBlanc. Vol. 74. Detroit: Gale, 2003. From Literature Resource Center. Document Type: Work overview, Critical essay Introduction Further Readings about the Topic Introduction Julius Caesar contains elements of both Shakespeare's histories and tragedies, and has been classified as a "problem play" by some scholars. Set in Rome in 44 b.c., the play describes a senatorial conspiracy to murder the emperor Caesar and the political turmoil that ensues in the aftermath of the assassination. The emperor's demise, however, is not the primary concern for critics of Julius Caesar; rather, most critics are interested in the events surrounding the act--the organization of the conspiracy against Caesar and the personal and political repercussions of the murder. Shakespeare's tragedies often feature the death of the titular character at the play's end. Many commentators have noted that Julius Caesar's unusual preempting of this significant event--Caesar is killed less than halfway through the play--diminishes the play's power early in the third act. Scholars are interested in the play's unconventional structure and its treatment of political conflict, as well as Shakespeare's depiction of Rome and the struggles the central characters face in balancing personal ambition, civic duty, and familial obligation. Modern critics also study the numerous social and religious affinities that Shakespeare's Rome shares with Elizabethan England.