Chapter 3: EDWARD KAMAU BRATHWAITE: VISHWAKARMA ARRIVES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dionne Brand's Global Intimacies: Practising Affective Citizenship

Dionne Brand’s Global Intimacies: Practising Affective Citizenship Diana Brydon “I say this big world is the story, I don’t have any other” (Inventory 84) Rosi Braidotti suggests that “The human has been subsumed in global relations of intimacy, complicity and proximity with forces of the inhuman and post-human kind: scientific, industrial and military complexes, global communication networks, processes of commodification and exchange on a global scale” (264). She argues further that it is the task of critical theory to track the “fluctuations“ of this new disorder (264). In this paper I ask what tracking these fluctuations involves, for the poet Dionne Brand who sets herself this task in her long poem, Inventory, and for the critic who reads her work fully attentive to the historical legacies of humanism and their entanglements with the humanities and the humanitarian.1 The CFP for this special issue asks two related questions that I pursue here: “what good is the study of literature?” and “how does the turn to ethics position literary criticism in relation to politics?” It is not possible to answer these questions definitively. In this paper, I follow Brand’s lead into registering the visceral force of the kinds of global intimacies enumerated by Braidotti in order to ask what these practices imply for the political projects of citizenship and community in contemporary times. I argue that to fully grasp the implications of how Brand’s poetry engages and is engaged in these emerging global complicities, critics need to attend to the dynamics of the experiential dimensions of its affect as well as its explicit meaning.2 “On Poetry,” the last essay in Dionne Brand’s Bread Out of Stone, concludes: “Poetry is here, just here. -

LOCATING the IDEAL HOMELAND TN the LITERATURE of EDWIDGE DANTICAT by JULIANE OKOT BITEK B.F.A., the University of British Columb

LOCATING THE IDEAL HOMELAND TN THE LITERATURE OF EDWIDGE DANTICAT by JULIANE OKOT BITEK B.F.A., The University of British Columbia, 1995 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULIFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) May2009 © Juliane Okot Bitek, 2009 ABSTRACT Edwidge Danticat, who has lived most of her life in the United States, retains a strong link with Haiti and primarily writes about the Haitian experience inside and outside the country. For Danticat, the ‘ideal homeland’ is a psychic space where she can be Haitian, American, and belong to both countries. Danticat’s aspiration and position as one who can make claim to both Haiti and the United States somewhat supports Stuart Hall’s notion of cultural identity as a fluid entity and an identity that is becoming and is, not one that is static and was. However, Danticat locates her ‘ideal homeland’ within the Haitian Dyaspora, as a social construct that includes all the people of the Haitian descent in the diaspora, whatever their countries of citizenship. This ideal homeland is an emotional and literary space for continued expression and creation of Haitian identity, history and culture. It is not a geographical space and as such, requires that membership in it engage through text. This paper investigates ways in which Danticat expresses the ideal homeland in her fiction and nonfiction works. I use Dionne Brand, Kamau Brathwaite, Edward Soja and Judith Lewis Herman among others, as theorists to discover this ideal homeland in order to show that Danticat, like many diasporic writers, is actively engaged in locating for themselves where they can engage in their work as they create new communities and take charge of how they tell their stories and how they identify themselves. -

The Elements of Poet :Y

CHAPTER 3 The Elements of Poet :y A Poetry Review Types of Poems 1, Lyric: subjective, reflective poetry with regular rhyme scheme and meter which reveals the poet’s thoughts and feelings to create a single, unique impres- sion. Matthew Arnold, "Dover Beach" William Blake, "The Lamb," "The Tiger" Emily Dickinson, "Because I Could Not Stop for Death" Langston Hughes, "Dream Deferred" Andrew Marvell, "To His Coy Mistress" Walt Whitman, "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking" 2. Narrative: nondramatic, objective verse with regular rhyme scheme and meter which relates a story or narrative. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, "Kubla Khan" T. S. Eliot, "Journey of the Magi" Gerard Manley Hopkins, "The Wreck of the Deutschland" Alfred, Lord Tennyson, "Ulysses" 3. Sonnet: a rigid 14-line verse form, with variable structure and rhyme scheme according to type: a. Shakespearean (English)--three quatrains and concluding couplet in iambic pentameter, rhyming abab cdcd efe___~f gg or abba cddc effe gg. The Spenserian sonnet is a specialized form with linking rhyme abab bcbc cdcd ee. R-~bert Lowell, "Salem" William Shakespeare, "Shall I Compare Thee?" b. Italian (Petrarchan)--an octave and sestet, between which a break in thought occurs. The traditional rhyme scheme is abba abba cde cde (or, in the sestet, any variation of c, d, e). Elizabeth Barrett Browning, "How Do I Love Thee?" John Milton, "On His Blindness" John Donne, "Death, Be Not Proud" 4. Ode: elaborate lyric verse which deals seriously with a dignified theme. John Keats, "Ode on a Grecian Urn" Percy Bysshe Shelley, "Ode to the West Wind" William Wordsworth, "Ode: Intimations of Immortality" Blank Verse: unrhymed lines of iambic pentameter. -

Creole Modernism

ANKHI MUKHERJEE Creole Modernism As affirmations of the modern go, few can match the high spirits of Susan Stanford Friedman’s invitation to formulate a “planetary epistemology” of modernist studies. As she explains in a footnote, Friedman uses the term “planetarity” in a different sense than Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak in Death of a Discipline, where the latter proposes that “if we imagine ourselves as planetary subjects rather than global agents, planetary creatures rather than global entities, alterity remains underived from us.”1 If Spivak’s planet-thought is a “utopian gesture of resistance against globalization as the geohistorical and economic domination of the Global South,” Friedman’s own use of the term ‘planetarity’ is epistemological, implying “a consciousness of the earth as planet, not restricted to geopolitical formations and potentially encompassing the non-human as well as the human.”2 Friedman’s planetary epistemology needs the playground of “modernism/modernity,” the slash denoting a simultaneous separation and connection, “the paradox of all borders,” which she considers to be richly generative (475). For modernism is not simply outside or after modernity, a belated reaction to the shock of it. It is contained within modernity (or particular modernities) as its aesthetic domain, and interacts with other domains, commercial, technological, societal, and governmental. It follows that “Every modernity has its distinctive modernism” (475). Pluralizing the key terms to engage with the polylogue of languages and cultures issuing from forms of modernism/modernity everywhere, Friedman’s invocation of this transformational (planetary) model of cultural circulation opens up possibilities for modernist studies to venture fearlessly outside the Anglo-American field and into “elsewhere” places that constitute modernism’s Other: the colonies and ex- colonies of South Asia and the Caribbean, the American South, and the Diaspora. -

Gcse English Literature (8702)

GCSE ENGLISH LITERATURE (8702) Past and present: poetry anthology For exams from 2017 Version 1.0 June 2015 AQA_EngLit_GCSE_v08.indd 1 31/07/2015 22:14 AQA GCSE English Literature Past and present: poetry anthology All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing on any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the publisher, except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of the licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Notice to teachers: It is illegal to reproduce any part of this work in material form (including photocopying and electronic storage) except under the following circumstances: i) where you are abiding by a licence granted to your school or institution by the Copyright Licensing Agency; ii) where no such licence exists, or where you wish to exceed the terms of a licence, and you have gained the written permission of The Publishers Licensing Society; iii) where you are allowed to reproduce without permission under the provisions of Chapter 3 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Photo permissions 5 kieferpix / Getty Images, 6 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 8 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 9 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 11 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 12 Photos.com/Thinkstock, 13 Stuart Clarke/REX, 16 culture-images/Lebrecht, 16,© Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy, 17 Topfoto.co.uk, 18 Schiffer-Fuchs/ullstein -

Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning Was a Romantic Poet in Great Effect When Disclosing a Macabre Or Every Sense of the Word

THE GREAT Robert POETS Browning POETRY Read by David Timson and Patience Tomlinson NA192212D 1 How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix 3:49 2 Life in a Love 1:11 3 A Light Woman 3:42 4 The Statue and the Bust 15:16 5 My Last Duchess 3:53 6 The Confessional 4:59 7 A Grammarian’s Funeral 8:09 8 The Pied Piper of Hamelin 7:24 9 ‘You should have heard the Hamelin people…’ 8:22 10 The Lost Leader 2:24 11 Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister 3:55 12 The Laboratory 3:40 13 Porphyria’s Lover 3:47 14 Evelyn Hope 3:49 15 Home Thoughts from Abroad 1:19 16 Pippa’s Song 0:32 Total time: 76:20 = David Timson = Patience Tomlinson 2 Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning was a romantic poet in great effect when disclosing a macabre or every sense of the word. He was an ardent evil narrative, as in The Laboratory, or The lover who wooed the poet Elizabeth Confessional or Porphyria’s Lover. Barrett despite fierce opposition from Sometimes Browning uses this matter- her tyrannical father, while as a poet – of-fact approach to reduce a momentous inheriting the mantle of Wordsworth, occasion to the colloquial – in The Keats and Shelley – he sought to show, Grammarian’s Funeral, for instance, in in the Romantic tradition, man’s struggle which a scholar has spent his life pursuing with his own nature and the will of God. knowledge at the expense of actually But Browning was no mere imitator of enjoying life itself. -

My Last Duchess Porphyria's Lover Robert Browning 1812–1889

The Influence of Romanticism My Last Duchess RL 1 Cite strong and thorough Porphyria’s Lover textual evidence to support inferences drawn from the Poetry by Robert Browning text. RL 5 Analyze how an author’s choices concerning how to structure specific parts KEYWORD: HML12-944A of a text contribute to its overall VIDEO TRAILER structure and meaning as well as its aesthetic impact. RL 10 Read and comprehend literature, Meet the Author including poems. SL 1 Initiate and participate effectively in a range of collaborative discussions. Robert Browning 1812–1889 “A minute’s success,” remarked the poet character in an emotionally charged situation. Robert Browning, “pays for the failure of While critics attacked his early dramatic years.” Browning spoke from experience: poems, finding them difficult to understand, did you know? for years, critics either ignored or belittled Browning did not allow the reviews to keep his poetry. Then, when he was nearly 60, him from continuing to develop this form. Robert Browning . he became an object of near-worship. • became an ardent Secret Love In 1845, Browning met the admirer of Percy Bysshe Precocious Child An exceptionally bright poet Elizabeth Barrett and began a famous Shelley at age 12. child, Browning learned to read and write romance that has been memorialized in both • achieved fluency in by the time he was 5 and composed his film and literature. Against the wishes of Latin, Greek, Italian, and first, unpublished volume of poetry at Barrett’s overbearing father, the two poets French by age 14. 12. At the age of 21 he published his first married in secret in 1846 and eloped to • wrote the children’s book, Pauline (1833), to negative reviews. -

Kamau Brathwaite's Born to Slow Horses And

THE GRIFFIN TRUST For Excellence In Poetry Trustees: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Margaret Atwood KAMAU BRATHWAITE’S BORN TO SLOW HORSES Carolyn Forché AND Scott Griffin SYLVIA LEGRIS’ NERVE SQUALL Robert Hass WIN THE 2006 GRIFFIN POETRY PRIZE Michael Ondaatje Robin Robertson Toronto, ON (June 1, 2006) – Kamau Brathwaite and Sylvia Legris are the International and Canadian winners of the 6th annual Griffin Poetry Prize. The C$100,000 Griffin Poetry David Young Prize, the richest prize in the world for a single volume of poetry, is divided between the two winners. The prize is for first edition books of poetry, including translations, published in English in 2005, and submitted from anywhere in the world. The awards event was hosted by Scott Griffin, founder of the prize. Simon Armitage, renowned poet, author and playwright assumed the role of Master of Ceremonies. Judges Lisa Robertson and Eliot Weinberger announced the International and Canadian winners for 2006. More than 400 guests celebrated the awards, including former Governor-General, the Right Honourable Adrienne Clarkson, acclaimed Canadian actors Albert Schultz and Sarah Polley, Senator Jerry Grafstein and his wife Carol, among others. In addition, poets, publishers and other literary luminaries attended the celebration. The evening’s theme was Shangri-La and featured a silk route marketplace replete with banners of fuschia, purple and gold. Hundreds of pigmy orchids and butterflies in a dizzying array of colours adorned the room. The event, which took place at The Stone Distillery in Toronto, offered up a menu of decidedly Asian fusion cuisine. Appetizers included mango and Thai basil sushi rolls, deep-fried plantain, sweet corn tamales, crab cakes on a bed of remoulade, and a sweet potato and jicama salad. -

James Kelman's Interview with John La Rose

The full interview with John La Rose1 More than twenty five years ago I was asked to interview John La Rose for the arts and culture journal Variant 19. Malcolm Dickson was then editor. The interview took place in John’s house in Finsbury Park. Malcolm organized the recording apparatus and also jumped about taking photographs. I had known John for a few years by then and had been in his company quite often; my only plan, therefore, was to start talking. He was a very strong and experienced orator, and with a tremendous breadth of knowledge. He was used to the toughest forms of meetings, those that began in confrontation and moved towards negotiation. I knew he would go where he thought necessary and return near enough to the starting point: my job was to resist interfering. The general population are unaware of the depth and complexity of the struggle of black people and other minorities in the United Kingdom. This transcription of a talk by John La Rose allows an insight into that and of the richness of the Caribbean side of its social and intellectual tradition. Insight here is gained into the inseparable nature of the culture and the political. There is also the matter of John's own centrality to some of the more crucial political interventions in his time. It should be a matter of concern how easily such a figure can be airbrushed from the political and cultural history of the UK, and the fundamental role played by John La Rose, his peers and contemporaries. -

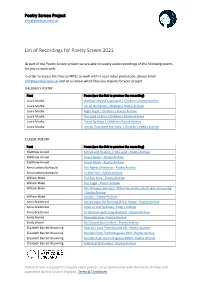

List of Recordings for Poetry Screen 2021

Poetry Screen Project [email protected] List of Recordings for Poetry Screen 2021 As part of the Poetry Screen project we are able to supply audio recordings of the following poems for you to work with. In order to access this files as MP3s to work with in your video production, please email [email protected] and let us know which files you require for your project. CHILDREN’S POETRY Poet Poem (use the link to preview the recording) Laura Mucha Wanted: Wizard's Assistant | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha I'm an Orchestra | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha Night Flight | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha The Land of Blue | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha Travel By Book | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha Words That Make Me Smile | Children's Poetry Archive CLASSIC POETRY Poet Poem (use the link to preview the recording) Matthew Arnold Sohrab and Rustum, ll. 857–end - Poetry Archive Matthew Arnold Dover Beach - Poetry Archive Matthew Arnold Dover Beach - Poetry Archive Anna Laetitia Barbauld The Rights of Woman - Poetry Archive Anna Laetitia Barbauld To the Poor - Poetry Archive William Blake The Sick Rose - Poetry Archive William Blake The Tyger - Poetry Archive William Blake The Chimney Sweeper: 'When my mother died I was very young' - Poetry Archive William Blake London - Poetry Archive Anne Bradstreet Verses Upon the Burning of Our House - Poetry Archive Anne Bradstreet Upon a Fit of Sickness - Poetry Archive Anne Bradstreet To My Dear and Living Husband - Poetry Archive Emily Bronté Remembrance - Poetry Archive Emily Bronté No Coward Soul Is Mine - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning How do I Love Thee (Sonnet 43) - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning Sonnets From The Portuguese XXIV - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning Sonnets from the Portuguese XXXVI - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning A Musical Instrument - Poetry Archive Poetry Screen is a project to inspire video poetry, run in partnership with the Poetry Archive and supported by Arts Council England. -

Poetics, Time and Black Experimental Writing

After the End of the World: Poetics, Time and Black Experimental Writing by Anthony Reed This thesis/dissertation document has been electronically approved by the following individuals: Farred,Grant Aubrey (Chairperson) Maxwell,Barry Hamilton (Minor Member) Villarejo,Amy (Minor Member) Culler,Jonathan Dwight (Additional Member) AFTER THE END OF THE WORLD: POETICS, TIME, AND BLACK EXPERIMENTAL WRITING A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Anthony Reed August 2010 © 2010 Anthony Reed AFTER THE END OF THE WORLD: POETICS, TIME, AND BLACK EXPERIMENTAL WRITING Anthony Reed, Ph. D. Cornell University 2010 "After the End of the World" is a study of the poetics of experimental writing, focusing on the work of W. E. B. Du Bois, Nathaniel Mackey, Suzan-Lori Parks and Kamau Brathwaite. By thinking form as a locus of political and conceptual contestation and transformation, I seek methods for conceiving politics in literature apart from its references or the identities of authors and characters. Writing in different genres, and with different political investments, each of these authors offers resources for re-imagining community as a project, for thinking the constitution of the self and political subject, and for conceiving politics and literary studies globally. Using a broad conception of literary experimentation as writing that departs from conventional forms and conventional thinking, I emphasize time of reading, among other times. Arguing that conceptions of time tend to be at the heart of political concerns throughout the sites of the African diaspora, this project challenges those notions of black writing that rest on the binary or oppression/resistance. -

The Self in the Song: Identity and Authority in Contemporary

The Self in the Song: Identity and Authority in Contemporary American Poetry by David William Lucas A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Linda K. Gregerson, Chair Professor Yopie Prins Associate Professor Gillian Cahill White Professor John A. Whittier-Ferguson for my teachers ii Acknowledgments My debts are legion. I owe so much to so many that I can articulate only a partial index of my gratitude here: To Jonathan Farmer and At Length, in which an adapted and excerpted version of “The Nothing That I Am: Mark Strand” first appeared, as “On Mark Strand, The Monument.” To Steven Capuozzo, Amy Dawson, and the Literature Department staff of the Cleveland Public Library for their assistance with my research. To the Department of English Language and Literature and the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan for the financial and logistical support that allowed me to begin and finish this project. To the Stanley G. and Dorothy K. Harris Fund for a summer grant that allowed me to continue my work without interruption. To the Poetry & Poetics Workshop at the University of Michigan, and in particular to Julia Hansen, for their assistance in a workshop of the introduction to this study. To my teachers at the University of Michigan, and especially to Larry Goldstein and Marjorie Levinson, whose interest in this project, support of it, and suggestions for it have proven invaluable. To June Howard, A. Van Jordan, Benjamin Paloff, and Doug Trevor.