An Examination of the Conclusions to Browning's Dramatic Monologues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RAPHAEL JONATHAM DE OLIVEIRA SOARES.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ RAPHAEL JONATHAM DE OLIVEIRA SOARES HA PRAZER EM CANTAR: UMA INTRODUÇÃO À POESIA DE ROBERT BROWNING CURITIBA 2017 RAPHAEL JONATHAM DE OLIVEIRA SOARES HÁ PRAZER EM CANTAR: UMA INTRODUÇÃO À POESIA DE ROBERT BROWNING Dissertação apresentada ao Curso de Pós- Graduação em Letras, Setor de Humanas, da Universidade Federal do Paraná, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre em Letras. Orientador(a): Prof(a). Dr(a). Caetano Waldrigues Galindo. CURITIBA 2017 FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA ELABORADA PELO SISTEMA DE BIBLIOTECAS/UFPR - BIBLIOTECA DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS COM OS DADOS FORNECIDOS PELO AUTOR ___________ Fernanda Emanoéla Nogueira - CRB 9/1607_____________________ Soares, Raphael Jonatham de Oliveira Há prazer em cantar : uma introdução à poesia de Robert Browning. / Raphael Jonatham de Oliveira Soares. - Curitiba, 2017. Dissertação (Mestrado em Letras) - Setor de Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal do Paraná. Orientador : Prof. Dr. Caetano Waldrigues Galindo 1. Browning, Robert, 1812-1889 - Crítica e interpretação. 2. Poesia inglesa. 3. Tradução e interpretação. I. Galindo, Caetano Waldrigues, 1973-. II. Título. CDD - 821.8 MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAI DO PARANÁ PRÓ-REITORIA DE PESQUISA E PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO Setor CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS . UFPR Programa de Pós-Graduação LETRAS TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO Os membros da Banca Examinadora designada pelo Colegiado do Programa de Pós-Graduação em LETRAS da Universidade Federal do Paraná foram convocados para realizar a arguição da Dissertação de Mestrado de RAPHAEL JONATHAM DE OLIVEIRA SOARES intitulada: HÁ PRAZER EM CANTAR: UMA INTRODUÇÃO Á POESIA DE ROBERT BROWNING,após terem inquirido o aluno e realizado a avaliação do trabalho, são de parecer pela sua CÁ s -> > -» t /O, no rito de defesa. -

Title: the Disclosure of Self in Robert Browning's Dramatic Monologues

Title: The Disclosure of self in Robert Browning's dramatic monologues Author: Agnieszka Adamowicz-Pośpiech Adamowicz-Pośpiech Agnieszka. (2014). The Disclosure of Citation style: self in Robert Browning's dramatic monologues. W: W. Kalaga, M. Mazurek, M. Sarnek (red.) "Camouflage : secrecy and exposure in literary and cultural studies" (S. 112-126). Katowice : Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego Agnieszka Adamowicz-Pośpiech The Disclosure of Self in Robert Browning’s Dramatic Monologues “To read poems,” wrote George Eliot in a review of Browning’s work, “is often a substitute for thought; fine-sounding conventional phrases and the sing-song of verse demand no co-operation in the reader; they glide over the mind.”1 Contrary to Eliot’s assessment, the aim of this paper is to show that by creating a disturbing persona characterized by a fluctuating self-consciousness which was distinctive not only of the fictional character but also of the listener/reader and the writer, Browning hampers uninvolved reading. In his dramatic monologues, the poet employs certain techniques to hide the real nature of his monologists, and the reader is forced painstakingly to gather the dispersed allusions, implications and insinuations so as to uncover the secrets of the speakers. Doubleness in Victorian poetry has been perceived by some critics as one of its defining characteristics.2 Amongst the terms coined to describe it is E.D.H. Johnson’s “dark companion”: “The expressed content [of a poem] has a dark companion, its imaginative counterpart, which accompanies and comments on apparent meaning in such a way as to suggest ulterior motives.”3 Isobel Armstrong proposed a parallel concept “double companion.”4 However, the essential words, seem to me, to be the “imaginative counterpart” – since it is only in the imagination of the reader that the counterpart may arise on condition that the reader becomes involved in unraveling the text. -

The Elements of Poet :Y

CHAPTER 3 The Elements of Poet :y A Poetry Review Types of Poems 1, Lyric: subjective, reflective poetry with regular rhyme scheme and meter which reveals the poet’s thoughts and feelings to create a single, unique impres- sion. Matthew Arnold, "Dover Beach" William Blake, "The Lamb," "The Tiger" Emily Dickinson, "Because I Could Not Stop for Death" Langston Hughes, "Dream Deferred" Andrew Marvell, "To His Coy Mistress" Walt Whitman, "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking" 2. Narrative: nondramatic, objective verse with regular rhyme scheme and meter which relates a story or narrative. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, "Kubla Khan" T. S. Eliot, "Journey of the Magi" Gerard Manley Hopkins, "The Wreck of the Deutschland" Alfred, Lord Tennyson, "Ulysses" 3. Sonnet: a rigid 14-line verse form, with variable structure and rhyme scheme according to type: a. Shakespearean (English)--three quatrains and concluding couplet in iambic pentameter, rhyming abab cdcd efe___~f gg or abba cddc effe gg. The Spenserian sonnet is a specialized form with linking rhyme abab bcbc cdcd ee. R-~bert Lowell, "Salem" William Shakespeare, "Shall I Compare Thee?" b. Italian (Petrarchan)--an octave and sestet, between which a break in thought occurs. The traditional rhyme scheme is abba abba cde cde (or, in the sestet, any variation of c, d, e). Elizabeth Barrett Browning, "How Do I Love Thee?" John Milton, "On His Blindness" John Donne, "Death, Be Not Proud" 4. Ode: elaborate lyric verse which deals seriously with a dignified theme. John Keats, "Ode on a Grecian Urn" Percy Bysshe Shelley, "Ode to the West Wind" William Wordsworth, "Ode: Intimations of Immortality" Blank Verse: unrhymed lines of iambic pentameter. -

Gcse English Literature (8702)

GCSE ENGLISH LITERATURE (8702) Past and present: poetry anthology For exams from 2017 Version 1.0 June 2015 AQA_EngLit_GCSE_v08.indd 1 31/07/2015 22:14 AQA GCSE English Literature Past and present: poetry anthology All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing on any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the publisher, except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of the licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Notice to teachers: It is illegal to reproduce any part of this work in material form (including photocopying and electronic storage) except under the following circumstances: i) where you are abiding by a licence granted to your school or institution by the Copyright Licensing Agency; ii) where no such licence exists, or where you wish to exceed the terms of a licence, and you have gained the written permission of The Publishers Licensing Society; iii) where you are allowed to reproduce without permission under the provisions of Chapter 3 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Photo permissions 5 kieferpix / Getty Images, 6 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 8 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 9 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 11 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 12 Photos.com/Thinkstock, 13 Stuart Clarke/REX, 16 culture-images/Lebrecht, 16,© Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy, 17 Topfoto.co.uk, 18 Schiffer-Fuchs/ullstein -

Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning Was a Romantic Poet in Great Effect When Disclosing a Macabre Or Every Sense of the Word

THE GREAT Robert POETS Browning POETRY Read by David Timson and Patience Tomlinson NA192212D 1 How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix 3:49 2 Life in a Love 1:11 3 A Light Woman 3:42 4 The Statue and the Bust 15:16 5 My Last Duchess 3:53 6 The Confessional 4:59 7 A Grammarian’s Funeral 8:09 8 The Pied Piper of Hamelin 7:24 9 ‘You should have heard the Hamelin people…’ 8:22 10 The Lost Leader 2:24 11 Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister 3:55 12 The Laboratory 3:40 13 Porphyria’s Lover 3:47 14 Evelyn Hope 3:49 15 Home Thoughts from Abroad 1:19 16 Pippa’s Song 0:32 Total time: 76:20 = David Timson = Patience Tomlinson 2 Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning was a romantic poet in great effect when disclosing a macabre or every sense of the word. He was an ardent evil narrative, as in The Laboratory, or The lover who wooed the poet Elizabeth Confessional or Porphyria’s Lover. Barrett despite fierce opposition from Sometimes Browning uses this matter- her tyrannical father, while as a poet – of-fact approach to reduce a momentous inheriting the mantle of Wordsworth, occasion to the colloquial – in The Keats and Shelley – he sought to show, Grammarian’s Funeral, for instance, in in the Romantic tradition, man’s struggle which a scholar has spent his life pursuing with his own nature and the will of God. knowledge at the expense of actually But Browning was no mere imitator of enjoying life itself. -

University Microfilms, a XERQ\Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

72- 19,021 NAPRAVNIK, Charles Joseph, 1936- CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OF ROBERT BROWNING. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D. , 1972 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, A XERQ\Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan (^Copyrighted by Charles Joseph Napravnlk 1972 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE UNIVERSITY OF OKIAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OP ROBERT BROWNING A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY CHARLES JOSEPH NAPRAVNIK Norman, Oklahoma 1972 CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OF ROBERT BROWNING PROVED DISSERTATION COMMITTEE PLEASE NOTE: Some pages may have indistinct print. Filmed as received. University Microfilms, A Xerox Education Company TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION...... 1 II. BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE.................. 10 III, THE RING, THE CIRCLE, AND IMAGES OF UNITY..................................... 23 IV. IMAGES OF FLOWERS, INSECTS, AND ROSES..................................... 53 V. THE GARDEN IMAGE......................... ?8 VI. THE LANDSCAPE OF LOVE....... .. ...... 105 FOOTNOTES........................................ 126 BIBLIOGRAPHY.............. ...................... 137 iii CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OP ROBERT BROWNING CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Since the founding of The Browning Society in London in 1881, eight years before the poet*a death, the poetry of Robert -

Victorian Supplemental

Revised Spring 2019 WESTERN UNIVERESITY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PhD QUALIFYING EXAMINATION READING LIST English 9914 (SF)/ 9934 (PF) SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR THE VICTORIAN PERIOD 1. Additional Instructions Students for whom the nineteenth century is their Primary Field should supplement the general list with material chosen from the following, as suits the particular focus of their studies. Students who choose to concentrate on the Victorian Period within their major field should reduce the material on the Romantic part of the nineteenth-century list by approximately two thirds, and should replace this material with material drawn from the following list. In addition, the list for the major or primary field should contain 20% more material overall than for the secondary field. OPTIONAL TEXTS POETRY E. Barrett Browning: “A Sea-Side Walk”; “Felicia Hemans”; “Bertha in the Lane”; “Grief”; “To George Sand: A Desire”; “To George Sand: A Recognition”; “Hiram Powers’ ‘Greek Slave’”; “Sonnets from The Portuguese”; Aurora Leigh; “Lord Walter’s Wife”; “The Best Thing in the World”; “Mother and Poet”. Alfred Lord Tennyson: Song (‘A spirit haunts the year’s last hours’); “The Kraken”; “The Hesperides”; “To---. With the Following Poem”; “The Palace of Art “St Simeon Stylites”; “Break, Break, Break”; “Locksley Hall”; from The Princess ‘Sweet and low, sweet and low’; ‘Tears, idle tears’; ‘Now sleeps the crimson petal’; ‘Come down, O maid’; “The Eagle”; “Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington”; “The Charge of the Light Brigade”; “Enoch Arden” ; “The Higher Pantheism”; “Rizpah”; Idylls of the King; ‘Frater Ave atque Vale’; “Demeter and Persephone”; “Far—Far—Away”; “To the Marquis of Dufferin and Ava”; “Crossing the Bar” Edward Fitgerald: The Rubayiat of Omar Khayyam. -

The Tomb of the Author in Robert Browning's Dramatic Monologues

Előd Pál Csirmaz The Tomb of the Author in Robert Browning’s Dramatic Monologues MA Thesis (for MA in English Language and Literature) Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE), Budapest, Hungary, 2006 Supervisor: Péter Dávidházi, Habil. Docent, DSc. Abstract Even after the death of the Author, its remains, its tomb appears to mark a text it cre- ated. Various readings and my analyses of Robert Browning’s six dramatic mono- logues, My Last Duchess, The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed’s Church, Andrea del Sarto, “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came,” Caliban upon Setebos and Rabbi Ben Ezra, suggest that it is not only possible to trace Authorial presence in dramatic monologues, where the Author is generally supposed to be hidden behind a mask, but often it even appears to be inevitable to consider an Authorial entity. This, while problematizes traditional anti-authorial arguments, do not entail the dreaded consequences of introducing an Author, as various functions of the Author and vari- ous Author-related entities are considered in isolation. This way, the domain of metanarrative-like Authorial control can be limited and the Author is turned from a threat into a useful tool in analyses. My readings are done with the help of notions and suggestions derived from two frameworks I introduce in the course of the argument. They not only help in tracing and investigating the Author and related entities, like the Inscriber or the Speaker, but they also provide an alternative description of the genre of the dramatic monologue. Előd P Csirmaz The Tomb of the Author ii Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 THE THEORY OF THE AUTHOR 1 2.1 A History of the Death of the Author 2 2.2 From the Methodological to the Ontological and Back: The Functions of the Author and its Death 3 A. -

My Last Duchess Porphyria's Lover Robert Browning 1812–1889

The Influence of Romanticism My Last Duchess RL 1 Cite strong and thorough Porphyria’s Lover textual evidence to support inferences drawn from the Poetry by Robert Browning text. RL 5 Analyze how an author’s choices concerning how to structure specific parts KEYWORD: HML12-944A of a text contribute to its overall VIDEO TRAILER structure and meaning as well as its aesthetic impact. RL 10 Read and comprehend literature, Meet the Author including poems. SL 1 Initiate and participate effectively in a range of collaborative discussions. Robert Browning 1812–1889 “A minute’s success,” remarked the poet character in an emotionally charged situation. Robert Browning, “pays for the failure of While critics attacked his early dramatic years.” Browning spoke from experience: poems, finding them difficult to understand, did you know? for years, critics either ignored or belittled Browning did not allow the reviews to keep his poetry. Then, when he was nearly 60, him from continuing to develop this form. Robert Browning . he became an object of near-worship. • became an ardent Secret Love In 1845, Browning met the admirer of Percy Bysshe Precocious Child An exceptionally bright poet Elizabeth Barrett and began a famous Shelley at age 12. child, Browning learned to read and write romance that has been memorialized in both • achieved fluency in by the time he was 5 and composed his film and literature. Against the wishes of Latin, Greek, Italian, and first, unpublished volume of poetry at Barrett’s overbearing father, the two poets French by age 14. 12. At the age of 21 he published his first married in secret in 1846 and eloped to • wrote the children’s book, Pauline (1833), to negative reviews. -

Overseas 2011

overSEAS 2011 This thesis was submitted by its author to the School of Eng- lish and American Studies, Eötvös Loránd University, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. It was found to be among the best theses submitted in 2011, therefore it was decorated with the School’s Outstanding Thesis Award. As such it is published in the form it was submitted in overSEAS 2011 (http://seas3.elte.hu/overseas/2011.html) C ERTIFICATE OF R ESEARCH By my signature below, I certify that my ELTE MA thesis, entitled “And I Choose Never to Stoop”: Focalisation and Diegesis in Robert Browning’s Complementary Dramatic Monologues is entirely the result of my own work, and that no degree has previously been conferred upon me for this work. In my thesis I have cited all the sources (printed, electronic or oral) I have used faithfully and have always indicated their origin. The electronic version of my thesis (in PDF format) is a true representation (identical copy) of this printed version. If this pledge is found to be false, I realize that I will be subject to penalties up to and including the forfeiture of the degree earned by my thesis. Date: 2nd May 2011. Signed: ....................................................... “And I Choose Never to Stoop”: Focalisation and Diegesis in Robert Browning’s Complementary Dramatic Monologues „Márpedig sértést nem tűrök”: Fokalizáció és diegézis Robert Browning párverseiben SZAKDOLGOZAT Vesztergom Janina Témavezető: Dr. Csikós Dóra egyetemi adjunktus MA in English Anglisztika MA Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem 2011 Abstract The first and foremost aim of my thesis is to demonstrate that a comparative analysis of Robert Browning‟s complementary dramatic monologues, “My Last Duchess – Ferrara” and “Count Gismond – Aix en Provence”, does not only lead to a better understanding of the individual poems, but also draws the readers‟ attention to significant aspects of interpretation which otherwise would remain unnoticed. -

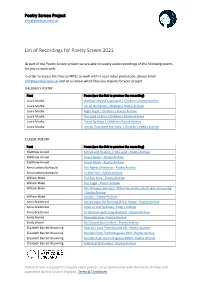

List of Recordings for Poetry Screen 2021

Poetry Screen Project [email protected] List of Recordings for Poetry Screen 2021 As part of the Poetry Screen project we are able to supply audio recordings of the following poems for you to work with. In order to access this files as MP3s to work with in your video production, please email [email protected] and let us know which files you require for your project. CHILDREN’S POETRY Poet Poem (use the link to preview the recording) Laura Mucha Wanted: Wizard's Assistant | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha I'm an Orchestra | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha Night Flight | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha The Land of Blue | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha Travel By Book | Children's Poetry Archive Laura Mucha Words That Make Me Smile | Children's Poetry Archive CLASSIC POETRY Poet Poem (use the link to preview the recording) Matthew Arnold Sohrab and Rustum, ll. 857–end - Poetry Archive Matthew Arnold Dover Beach - Poetry Archive Matthew Arnold Dover Beach - Poetry Archive Anna Laetitia Barbauld The Rights of Woman - Poetry Archive Anna Laetitia Barbauld To the Poor - Poetry Archive William Blake The Sick Rose - Poetry Archive William Blake The Tyger - Poetry Archive William Blake The Chimney Sweeper: 'When my mother died I was very young' - Poetry Archive William Blake London - Poetry Archive Anne Bradstreet Verses Upon the Burning of Our House - Poetry Archive Anne Bradstreet Upon a Fit of Sickness - Poetry Archive Anne Bradstreet To My Dear and Living Husband - Poetry Archive Emily Bronté Remembrance - Poetry Archive Emily Bronté No Coward Soul Is Mine - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning How do I Love Thee (Sonnet 43) - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning Sonnets From The Portuguese XXIV - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning Sonnets from the Portuguese XXXVI - Poetry Archive Elizabeth Barrett Browning A Musical Instrument - Poetry Archive Poetry Screen is a project to inspire video poetry, run in partnership with the Poetry Archive and supported by Arts Council England. -

The Victorian Newsletter

The Victorian Newsletter Deborah A. Logan, Editor Western Kentucky University Tables of Contents, #111 (2007) through #1 (1952) The Victorian Newsletter Number 111 Spring 2007 Contents Page Carlyle's Influence on Shakespeare 1 by Robert Sawyer Imagining Ophelia in Christina Rossetti's ''Sleeping at Last'' 8 by Mary Faraci The Poison Within: Robert Browning' s ''The Laboratory'' 10 by David Sonstroem ''Her life was in her books'': Jean lngelow in the Literary Marketplace 12 by Maura Ives The Buddhist Sub-Text and the Imperial Soul-Making in Kim 20 by Young Hee Kwon ''Gliding'': A Note On the Exquisite Delicacy of the Religious Glissade Motif in Hopkins's ''The Windhover'' 29 by Nathan Cervo Coming in The Victorian Newsletter 29 Books Received 30 Notice 32 The Victorian Newsletter Number 110 Fall 2006 Contents Page Reading Hodge: Preserving Rural Epistemologies in Hardy's Far from the Madding Crowd 1 by Eric G. Lorentzen Unmanned by Marriage and the Metropolis in Gissing's The Whirlpool 10 by Andrew Radford Anthony Trollope's Lady Anna and Shakespeare's Othello 18 by Maurice Hunt The Romantic and the Familiar: Third-Person Narrative in Chapter 11 of Bleak House 23 by David Paroissien Tennyson's In Memoriam, Section 123, and the Submarine Forest on the Lincolnshire Coast 28 by Patrick Scott Coming in Victorian Newsletter 30 Books Received 31 The Victorian Newsletter Number 109 Spring 2006 Contents Page Scandalous Sensations: The Woman In White on the Victorian Stage 1 by Maria K. Bachman Nostalgia to Amnesia: Charles Dickens, Marcus Clarke and Narratives of Australia’s Convict Origins 9 by Beth A.