Positron Annihilation 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Five Common Particles

The Five Common Particles The world around you consists of only three particles: protons, neutrons, and electrons. Protons and neutrons form the nuclei of atoms, and electrons glue everything together and create chemicals and materials. Along with the photon and the neutrino, these particles are essentially the only ones that exist in our solar system, because all the other subatomic particles have half-lives of typically 10-9 second or less, and vanish almost the instant they are created by nuclear reactions in the Sun, etc. Particles interact via the four fundamental forces of nature. Some basic properties of these forces are summarized below. (Other aspects of the fundamental forces are also discussed in the Summary of Particle Physics document on this web site.) Force Range Common Particles It Affects Conserved Quantity gravity infinite neutron, proton, electron, neutrino, photon mass-energy electromagnetic infinite proton, electron, photon charge -14 strong nuclear force ≈ 10 m neutron, proton baryon number -15 weak nuclear force ≈ 10 m neutron, proton, electron, neutrino lepton number Every particle in nature has specific values of all four of the conserved quantities associated with each force. The values for the five common particles are: Particle Rest Mass1 Charge2 Baryon # Lepton # proton 938.3 MeV/c2 +1 e +1 0 neutron 939.6 MeV/c2 0 +1 0 electron 0.511 MeV/c2 -1 e 0 +1 neutrino ≈ 1 eV/c2 0 0 +1 photon 0 eV/c2 0 0 0 1) MeV = mega-electron-volt = 106 eV. It is customary in particle physics to measure the mass of a particle in terms of how much energy it would represent if it were converted via E = mc2. -

1.1. Introduction the Phenomenon of Positron Annihilation Spectroscopy

PRINCIPLES OF POSITRON ANNIHILATION Chapter-1 __________________________________________________________________________________________ 1.1. Introduction The phenomenon of positron annihilation spectroscopy (PAS) has been utilized as nuclear method to probe a variety of material properties as well as to research problems in solid state physics. The field of solid state investigation with positrons started in the early fifties, when it was recognized that information could be obtained about the properties of solids by studying the annihilation of a positron and an electron as given by Dumond et al. [1] and Bendetti and Roichings [2]. In particular, the discovery of the interaction of positrons with defects in crystal solids by Mckenize et al. [3] has given a strong impetus to a further elaboration of the PAS. Currently, PAS is amongst the best nuclear methods, and its most recent developments are documented in the proceedings of the latest positron annihilation conferences [4-8]. PAS is successfully applied for the investigation of electron characteristics and defect structures present in materials, magnetic structures of solids, plastic deformation at low and high temperature, and phase transformations in alloys, semiconductors, polymers, porous material, etc. Its applications extend from advanced problems of solid state physics and materials science to industrial use. It is also widely used in chemistry, biology, and medicine (e.g. locating tumors). As the process of measurement does not mostly influence the properties of the investigated sample, PAS is a non-destructive testing approach that allows the subsequent study of a sample by other methods. As experimental equipment for many applications, PAS is commercially produced and is relatively cheap, thus, increasingly more research laboratories are using PAS for basic research, diagnostics of machine parts working in hard conditions, and for characterization of high-tech materials. -

Chapter 3 the Fundamentals of Nuclear Physics Outline Natural

Outline Chapter 3 The Fundamentals of Nuclear • Terms: activity, half life, average life • Nuclear disintegration schemes Physics • Parent-daughter relationships Radiation Dosimetry I • Activation of isotopes Text: H.E Johns and J.R. Cunningham, The physics of radiology, 4th ed. http://www.utoledo.edu/med/depts/radther Natural radioactivity Activity • Activity – number of disintegrations per unit time; • Particles inside a nucleus are in constant motion; directly proportional to the number of atoms can escape if acquire enough energy present • Most lighter atoms with Z<82 (lead) have at least N Average one stable isotope t / ta A N N0e lifetime • All atoms with Z > 82 are radioactive and t disintegrate until a stable isotope is formed ta= 1.44 th • Artificial radioactivity: nucleus can be made A N e0.693t / th A 2t / th unstable upon bombardment with neutrons, high 0 0 Half-life energy protons, etc. • Units: Bq = 1/s, Ci=3.7x 1010 Bq Activity Activity Emitted radiation 1 Example 1 Example 1A • A prostate implant has a half-life of 17 days. • A prostate implant has a half-life of 17 days. If the What percent of the dose is delivered in the first initial dose rate is 10cGy/h, what is the total dose day? N N delivered? t /th t 2 or e Dtotal D0tavg N0 N0 A. 0.5 A. 9 0.693t 0.693t B. 2 t /th 1/17 t 2 2 0.96 B. 29 D D e th dt D h e th C. 4 total 0 0 0.693 0.693t /th 0.6931/17 C. -

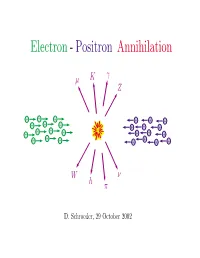

Electron - Positron Annihilation

Electron - Positron Annihilation γ µ K Z − − − + + + − − − + + + − − − − + + + − − − + + + + W ν h π D. Schroeder, 29 October 2002 OUTLINE • Electron-positron storage rings • Detectors • Reaction examples e+e− −→ e+e− [Inventory of known particles] e+e− −→ µ+µ− e+e− −→ q q¯ e+e− −→ W +W − • The future:Linear colliders Electron-Positron Colliders Hamburg Novosibirsk 11 GeV 12 GeV 47 GeV Geneva 200 GeV Ithaca Tokyo Stanford 12 GeV 64 GeV 8 GeV 12 GeV 30 GeV 100 GeV Beijing 12 GeV 4 GeV Size (R) and Cost ($) of an e+e− Storage Ring βE4 $=αR + ( E = beam energy) R d $ βE4 Find minimum $: 0= = α − dR R2 β =⇒ R = E2, $=2 αβ E2 α SPEAR: E = 8 GeV, R = 40 m, $ = 5 million LEP: E = 200 GeV, R = 4.3 km, $ = 1 billion + − + − Example 1: e e −→ e e e− total momentum = 0 θ − total energy = 2E e e+ Probability(E,θ)=? e+ E-dependence follows from dimensional analysis: density = ρ− A density = ρ+ − + × 2 Probability = (ρ− ρ+ − + A) (something with units of length ) ¯h ¯hc When E m , the only relevant length is = e p E 1 =⇒ Probability ∝ E2 at SPEAR Augustin, et al., PRL 34, 233 (1975) 6000 5000 4000 Ecm = 4.8 GeV 3000 2000 Number of Counts 1000 Theory 0 −0.8 −0.40 0.40.8 cos θ Prediction for e+e− −→ e+e− event rate (H. J. Bhabha, 1935): event dσ e4 1 + cos4 θ 2 cos4 θ 1 + cos2 θ ∝ = 2 − 2 + rate dΩ 32π2E2 4 θ 2 θ 2 cm sin 2 sin 2 Interpretation of Bhabha’sformula (R. -

QCD at Colliders

Particle Physics Dr Victoria Martin, Spring Semester 2012 Lecture 10: QCD at Colliders !Renormalisation in QCD !Asymptotic Freedom and Confinement in QCD !Lepton and Hadron Colliders !R = (e+e!!hadrons)/(e+e!"µ+µ!) !Measuring Jets !Fragmentation 1 From Last Lecture: QCD Summary • QCD: Quantum Chromodymanics is the quantum description of the strong force. • Gluons are the propagators of the QCD and carry colour and anti-colour, described by 8 Gell-Mann matrices, !. • For M calculate the appropriate colour factor from the ! matrices. 2 2 • The coupling constant #S is large at small q (confinement) and large at high q (asymptotic freedom). • Mesons and baryons are held together by QCD. • In high energy collisions, jets are the signatures of quark and gluon production. 2 Gluon self-Interactions and Confinement , Gluon self-interactions are believed to give e+ q rise to colour confinement , Qualitative picture: •Compare QED with QCD •In QCD “gluon self-interactions squeeze lines of force into Gluona flux tube self-Interactions” ande- Confinementq , + , What happens whenGluon try self-interactions to separate two are believedcoloured to giveobjects e.g. qqe q rise to colour confinement , Qualitativeq picture: q •Compare QED with QCD •In QCD “gluon self-interactions squeeze lines of force into a flux tube” e- q •Form a flux tube, What of happensinteracting when gluons try to separate of approximately two coloured constant objects e.g. qq energy density q q •Require infinite energy to separate coloured objects to infinity •Form a flux tube of interacting gluons of approximately constant •Coloured quarks and gluons are always confined within colourless states energy density •In this way QCD provides a plausible explanation of confinement – but not yet proven (although there has been recent progress with Lattice QCD) Prof. -

The W and Z at LEP

50YEARSOFCERN The W and Z at LEP 1954-2004 The Large Electron Positron collider made significant contributions to the process of establishing the Standard Model as the basis for matter and 5 forces, and also built a platform for physics scenarios beyond the model. The Standard Model of particle physics is arguably one of the greatest achievements in physics in the 20th century. Within this framework the electroweak interactions, as introduced by Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam and Steven Weinberg, are formulated as an SU(2)xll(l) gauge field theory with the masses of the fundamental particles generated by the Higgs mechanism. Both of the first two crucial steps in establishing experimentally the electroweak part of the Standard Model occurred at CERN. These were the discovery of neutral currents in neutrino scattering by the Gargamelle collab oration in 1973, and only a decade later the discovery by the UA1 and UA2 collaborations of the W and Z gauge bosons in proton- antiproton collisions at the converted Super Proton Synchrotron (CERN Courier May 2003 p26 and April 2004 pl3). Establishing the theory at the quantum level was the next logical step, following the pioneering theoretical work of Gerard 't Hooft Fig. 1. The cover page and Martinus Veltman. Such experimental proof is a necessary (left) of the seminal requirement for a theory describing phenomena in the microscopic CERN yellow report world. At the same time, performing experimental analyses with high 76-18 on the physics precision also opens windows to new physics phenomena at much potential of a 200 GeV higher energy scales, which can be accessed indirectly through e+e~ collider, and the virtual effects. -

A Historical Review of the Discovery of the Quark and Gluon Jets

EPJ manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) JETS AND QCD: A Historical Review of the Discovery of the Quark and Gluon Jets and its Impact on QCD⋆ A.Ali1 and G.Kramer2 1 DESY, D-22603 Hamburg (Germany) 2 Universit¨at Hamburg, D-22761 Hamburg (Germany) Abstract. The observation of quark and gluon jets has played a crucial role in establishing Quantum Chromodynamics [QCD] as the theory of the strong interactions within the Standard Model of particle physics. The jets, narrowly collimated bundles of hadrons, reflect configurations of quarks and gluons at short distances. Thus, by analysing energy and angular distributions of the jets experimentally, the properties of the basic constituents of matter and the strong forces acting between them can be explored. In this review, which is primarily a description of the discovery of the quark and gluon jets and the impact of their obser- vation on Quantum Chromodynamics, we elaborate, in particular, the role of the gluons as the carriers of the strong force. Focusing on these basic points, jets in e+e− collisions will be in the foreground of the discussion and we will concentrate on the theory that was contempo- rary with the relevant experiments at the electron-positron colliders. In addition we will delineate the role of jets as tools for exploring other particle aspects in ep and pp/pp¯ collisions - quark and gluon densi- ties in protons, measurements of the QCD coupling, fundamental 2-2 quark/gluon scattering processes, but also the impact of jet decays of top quarks, and W ±, Z bosons on the electroweak sector. -

Probing 23% of the Universe at the Large Hadron Collider

Probing 23% of the Universe at the Large Hadron Collider Will Flanagan1 Advisor: Dr Teruki Kamon2 In close collaboration with Bhaskar Dutta2, Alfredo Gurrola2, Nikolay Kolev3, Tom Crockett2, Michael VanDyke2, and Abram Krislock2 1University of Colorado at Boulder, Cyclotron REU Program 2Texas A&M University 3University of Regina Introduction What is cosmologically significant about ‘focus Analysis With recent astronomical measurements, point’? We first decide which events we want to look for. χ~0 ~0 we know that 23% of the Universe is The 1is allowed to annihilate with itself since it is Since χ 1 is undetectable (otherwise it wouldn’t be ‘dark composed of dark matter, whose origin is its own antimatter particle. The χ~ 0 -χ~0 annihilation matter’!), we look for events with a 1 1 Red – Jet distribution unknown. Supersymmetry (SUSY), a leading cross section is typically too small (predicting a relic after MET cut large amount of missing transverse theory in particle physics, provides us with a cold dark χ~0 Z channel dark matter density that is too energy. Also, due to the nature of 1 u- matter candidate, the lightest supersymmetric particle Z0 large). The small µ of focus these decays (shown below) we also χ~0 (LSP). SUSY particles, including the LSP, can be 1 u point x require two energetic jets. 2 f 1 Ω ~0 ~h dx created at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN. allows for a larger annihilation χ1 ∫ 0 σ v { ann g~ 2 energetic jets + 2 leptons We perform a systematic study to characterize the cross section for our dark 0.23 698 u- + MET 2 g~ SUSY signals in the "focus point" region, one of a few matter candidate by opening πα ~ u - σ annv = 2 u l cosmologically-allowed parameter regions in our SUSY up the ‘Z channel’ (pictured 321 8M χ~0 l+ 0.9 pb 2 ~+ model. -

A Relativistic One Pion Exchange Model of Proton-Neutron Electron-Positron Pair Production

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1973 A Relativistic One Pion Exchange Model of Proton-Neutron Electron-Positron Pair Production William A. Peterson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Physics Commons Recommended Citation Peterson, William A., "A Relativistic One Pion Exchange Model of Proton-Neutron Electron-Positron Pair Production" (1973). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 3674. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/3674 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author sincerely appreciates the advice and encouragement of Dr. Jack E. Chatelain who suggested this problem and guided its progress. The author would also like to extend his deepest gratitude to Dr. V. G. Lind and Dr. Ackele y Miller for their support during the years of graduate school. William A. Pete r son iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS • ii LIST OF TABLES • v LIST OF FIGURES. vi ABSTRACT. ix Chapter I. INTRODUCTION. • . • • II. FORMULATION OF THE PROBLEM. 7 Green's Function Treatment of the Dirac Equation. • • • . • . • • • 7 Application of Feynman Graph Rules to Pair Production in Neutron- Proton Collisions 11 III. DIFFERENTIAL CROSS SECTION. 29 Symmetric Coplanar Case 29 Frequency Distributions 44 BIBLIOGRAPHY. 72 APPENDIXES •• 75 Appendix A. Notation and Definitions 76 Appendix B. Expressi on for Cross Section. 79 Appendix C. -

E+ E~ ANNIHILATION Hinrich Meyer, Fachbereich Physik, Universitдt

- 155 - e+e~ ANNIHILATION Hinrich Meyer, Fachbereich Physik, Universität Wuppertal, Fed. Rep. Germany CONTENT INTRODUCTION 1. e+e~ STORAGE RINGS .1 Energy and Size .2 Luminosity .3 Energy range of one Ring .4 Energie resolution .5 Polarization 2. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES .1 Storage Ring Detectors .2 Background .3 Luminosity Measurement .4 Radiative Corrections 3. QED-REACTIONS + . 1 e+e~ T T~ .2 e+e"+y+y~ . 3 e+e~ -»• e+e~ . 4 e+e_ •+y y 4. HADRON PRODUCTION IN e+e~ANNTHILATION .1 Total Cross Section .2 Average Event Properties .3 Two Jet Structure .4 Three Jet Structure .5 Gluon Properties - 156 - 5. SEARCH FOR NEW PARTICLES .1 Experimental Methods .2 Search for the sixth Flavor (t) .3 Properties of Q Q Resonances .4 New Leptons 6. YY ~ REACTIONS .1 General Properties .2 Resonance Production .3 £ for e,Y Scattering .4 Hard Scattering Processes .5 Photon Structure Function INTRODUCTION e+e storage rings have been proven to be an extremely fruitful techno• logical invention for particle physics. They were originally designed to provide stringent experimental tests of the theory of leptons and photons QED (Quantum-Electro-Dynamics). QED has passed these tests beautifully up to the highest energies (PETRA) so far achieved. The great successes of the e+e storage rings however are in the field of strong interaction physics. The list below gives a very brief overview of the historical development by quoting the highlights of physics results from e+e storage rings with the completion of storage rings of higher and higher energy (see Fig.1). YEAR -

Model of N¯ Annihilation in Experimental Searches for N¯ Transformations

PHYSICAL REVIEW D 99, 035002 (2019) Model of n¯ annihilation in experimental searches for n¯ transformations E. S. Golubeva,1 J. L. Barrow,2 and C. G. Ladd2 1Institute for Nuclear Research, Russian Academy of Sciences, Prospekt 60-letiya Oktyabrya 7a, Moscow, 117312, Russia 2University of Tennessee, Department of Physics, 401 Nielsen Physics Building, 1408 Circle Drive, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996, USA (Received 24 July 2018; published 5 February 2019) Searches for baryon number violation, including searches for proton decay and neutron-antineutron transformation (n → n¯), are expected to play an important role in the evolution of our understanding of beyond standard model physics. The n → n¯ is a key prediction of certain popular theories of baryogenesis, and experiments such as the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment and the European Spallation Source plan to search for this process with bound- and free-neutron systems. Accurate simulation of this process in Monte Carlo will be important for the proper reconstruction and separation of these rare events from background. This article presents developments towards accurate simulation of the annihilation process for 12 use in a cold, free neutron beam for n → n¯ searches from nC¯ annihilation, as 6 C is the target of choice for the European Spallation Source’s NNBar Collaboration. Initial efforts are also made in this paper to 40 perform analogous studies for intranuclear transformation searches in 18Ar nuclei. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevD.99.035002 I. INTRODUCTION evacuated, magnetically shielded pipe of 76 m in length (corresponding to a flight time of ∼0.1 s), until being A. Background 12 allowed to hit a target of carbon (6 C) foil (with a thickness As early as 1967, A. -

Neutrino Masses-How to Add Them to the Standard Model

he Oscillating Neutrino The Oscillating Neutrino of spatial coordinates) has the property of interchanging the two states eR and eL. Neutrino Masses What about the neutrino? The right-handed neutrino has never been observed, How to add them to the Standard Model and it is not known whether that particle state and the left-handed antineutrino c exist. In the Standard Model, the field ne , which would create those states, is not Stuart Raby and Richard Slansky included. Instead, the neutrino is associated with only two types of ripples (particle states) and is defined by a single field ne: n annihilates a left-handed electron neutrino n or creates a right-handed he Standard Model includes a set of particles—the quarks and leptons e eL electron antineutrino n . —and their interactions. The quarks and leptons are spin-1/2 particles, or weR fermions. They fall into three families that differ only in the masses of the T The left-handed electron neutrino has fermion number N = +1, and the right- member particles. The origin of those masses is one of the greatest unsolved handed electron antineutrino has fermion number N = 21. This description of the mysteries of particle physics. The greatest success of the Standard Model is the neutrino is not invariant under the parity operation. Parity interchanges left-handed description of the forces of nature in terms of local symmetries. The three families and right-handed particles, but we just said that, in the Standard Model, the right- of quarks and leptons transform identically under these local symmetries, and thus handed neutrino does not exist.