1.1. Introduction the Phenomenon of Positron Annihilation Spectroscopy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Five Common Particles

The Five Common Particles The world around you consists of only three particles: protons, neutrons, and electrons. Protons and neutrons form the nuclei of atoms, and electrons glue everything together and create chemicals and materials. Along with the photon and the neutrino, these particles are essentially the only ones that exist in our solar system, because all the other subatomic particles have half-lives of typically 10-9 second or less, and vanish almost the instant they are created by nuclear reactions in the Sun, etc. Particles interact via the four fundamental forces of nature. Some basic properties of these forces are summarized below. (Other aspects of the fundamental forces are also discussed in the Summary of Particle Physics document on this web site.) Force Range Common Particles It Affects Conserved Quantity gravity infinite neutron, proton, electron, neutrino, photon mass-energy electromagnetic infinite proton, electron, photon charge -14 strong nuclear force ≈ 10 m neutron, proton baryon number -15 weak nuclear force ≈ 10 m neutron, proton, electron, neutrino lepton number Every particle in nature has specific values of all four of the conserved quantities associated with each force. The values for the five common particles are: Particle Rest Mass1 Charge2 Baryon # Lepton # proton 938.3 MeV/c2 +1 e +1 0 neutron 939.6 MeV/c2 0 +1 0 electron 0.511 MeV/c2 -1 e 0 +1 neutrino ≈ 1 eV/c2 0 0 +1 photon 0 eV/c2 0 0 0 1) MeV = mega-electron-volt = 106 eV. It is customary in particle physics to measure the mass of a particle in terms of how much energy it would represent if it were converted via E = mc2. -

(Anti)Proton Mass and Magnetic Moment

FFK Conference 2019, Tihany, Hungary Precision measurements of the (anti)proton mass and magnetic moment Wolfgang Quint GSI Darmstadt and University of Heidelberg on behalf of the BASE collaboration spokesperson: Stefan Ulmer 2019 / 06 / 12 BASE – Collaboration • Mainz: Measurement of the magnetic moment of the proton, implementation of new technologies. • CERN Antiproton Decelerator: Measurement of the magnetic moment of the antiproton and proton/antiproton q/m ratio • Hannover/PTB: Laser cooling project, new technologies Institutes: RIKEN, MPI-K, CERN, University of Mainz, Tokyo University, GSI Darmstadt, University of Hannover, PTB Braunschweig C. Smorra et al., EPJ-Special Topics, The BASE Experiment, (2015) WE HAVE A PROBLEM mechanism which created the obvious baryon/antibaryon asymmetry in the Universe is not understood One strategy: Compare the fundamental properties of matter / antimatter conjugates with ultra-high precision CPT tests based on particle/antiparticle comparisons R.S. Van Dyck et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 59 , 26 (1987). Recent B. Schwingenheuer, et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 4376 (1995). Past CERN H. Dehmelt et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 83 , 4694 (1999). G. W. Bennett et al., Phys. Rev. D 73 , 072003 (2006). Planned M. Hori et al., Nature 475 , 485 (2011). ALICE G. Gabriesle et al., PRL 82 , 3199(1999). J. DiSciacca et al., PRL 110 , 130801 (2013). S. Ulmer et al., Nature 524 , 196-200 (2015). ALICE Collaboration, Nature Physics 11 , 811–814 (2015). M. Hori et al., Science 354 , 610 (2016). H. Nagahama et al., Nat. Comm. 8, 14084 (2017). M. Ahmadi et al., Nature 541 , 506 (2017). M. Ahmadi et al., Nature 586 , doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0017 (2018). -

Interactions of Antiprotons with Atoms and Molecules

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln US Department of Energy Publications U.S. Department of Energy 1988 INTERACTIONS OF ANTIPROTONS WITH ATOMS AND MOLECULES Mitio Inokuti Argonne National Laboratory Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdoepub Part of the Bioresource and Agricultural Engineering Commons Inokuti, Mitio, "INTERACTIONS OF ANTIPROTONS WITH ATOMS AND MOLECULES" (1988). US Department of Energy Publications. 89. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdoepub/89 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Energy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in US Department of Energy Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. /'Iud Tracks Radial. Meas., Vol. 16, No. 2/3, pp. 115-123, 1989 0735-245X/89 $3.00 + 0.00 Inl. J. Radial. Appl .. Ins/rum., Part D Pergamon Press pic printed in Great Bntam INTERACTIONS OF ANTIPROTONS WITH ATOMS AND MOLECULES* Mmo INOKUTI Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, Illinois 60439, U.S.A. (Received 14 November 1988) Abstract-Antiproton beams of relatively low energies (below hundreds of MeV) have recently become available. The present article discusses the significance of those beams in the contexts of radiation physics and of atomic and molecular physics. Studies on individual collisions of antiprotons with atoms and molecules are valuable for a better understanding of collisions of protons or electrons, a subject with many applications. An antiproton is unique as' a stable, negative heavy particle without electronic structure, and it provides an excellent opportunity to study atomic collision theory. -

BOTTOM, STRANGE MESONS (B = ±1, S = ∓1) 0 0 ∗ Bs = Sb, Bs = S B, Similarly for Bs ’S

Citation: P.A. Zyla et al. (Particle Data Group), Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys. 2020, 083C01 (2020) BOTTOM, STRANGE MESONS (B = ±1, S = ∓1) 0 0 ∗ Bs = sb, Bs = s b, similarly for Bs ’s 0 P − Bs I (J ) = 0(0 ) I , J, P need confirmation. Quantum numbers shown are quark-model predictions. Mass m 0 = 5366.88 ± 0.14 MeV Bs m 0 − mB = 87.38 ± 0.16 MeV Bs Mean life τ = (1.515 ± 0.004) × 10−12 s cτ = 454.2 µm 12 −1 ∆Γ 0 = Γ 0 − Γ 0 = (0.085 ± 0.004) × 10 s Bs BsL Bs H 0 0 Bs -Bs mixing parameters 12 −1 ∆m 0 = m 0 – m 0 = (17.749 ± 0.020) × 10 ¯h s Bs Bs H BsL = (1.1683 ± 0.0013) × 10−8 MeV xs = ∆m 0 /Γ 0 = 26.89 ± 0.07 Bs Bs χs = 0.499312 ± 0.000004 0 CP violation parameters in Bs 2 −3 Re(ǫ 0 )/(1+ ǫ 0 )=(−0.15 ± 0.70) × 10 Bs Bs 0 + − CKK (Bs → K K )=0.14 ± 0.11 0 + − SKK (Bs → K K )=0.30 ± 0.13 0 ∓ ± +0.10 rB(Bs → Ds K )=0.37−0.09 0 ± ∓ ◦ δB(Bs → Ds K ) = (358 ± 14) −2 CP Violation phase βs = (2.55 ± 1.15) × 10 rad λ (B0 → J/ψ(1S)φ)=1.012 ± 0.017 s λ = 0.999 ± 0.017 A, CP violation parameter = −0.75 ± 0.12 C, CP violation parameter = 0.19 ± 0.06 S, CP violation parameter = 0.17 ± 0.06 L ∗ 0 ACP (Bs → J/ψ K (892) ) = −0.05 ± 0.06 k ∗ 0 ACP (Bs → J/ψ K (892) )=0.17 ± 0.15 ⊥ ∗ 0 ACP (Bs → J/ψ K (892) ) = −0.05 ± 0.10 + − ACP (Bs → π K ) = 0.221 ± 0.015 0 + − ∗ 0 ACP (Bs → [K K ]D K (892) ) = −0.04 ± 0.07 HTTP://PDG.LBL.GOV Page1 Created:6/1/202008:28 Citation: P.A. -

A Discussion on Characteristics of the Quantum Vacuum

A Discussion on Characteristics of the Quantum Vacuum Harold \Sonny" White∗ NASA/Johnson Space Center, 2101 NASA Pkwy M/C EP411, Houston, TX (Dated: September 17, 2015) This paper will begin by considering the quantum vacuum at the cosmological scale to show that the gravitational coupling constant may be viewed as an emergent phenomenon, or rather a long wavelength consequence of the quantum vacuum. This cosmological viewpoint will be reconsidered on a microscopic scale in the presence of concentrations of \ordinary" matter to determine the impact on the energy state of the quantum vacuum. The derived relationship will be used to predict a radius of the hydrogen atom which will be compared to the Bohr radius for validation. The ramifications of this equation will be explored in the context of the predicted electron mass, the electrostatic force, and the energy density of the electric field around the hydrogen nucleus. It will finally be shown that this perturbed energy state of the quan- tum vacuum can be successfully modeled as a virtual electron-positron plasma, or the Dirac vacuum. PACS numbers: 95.30.Sf, 04.60.Bc, 95.30.Qd, 95.30.Cq, 95.36.+x I. BACKGROUND ON STANDARD MODEL OF COSMOLOGY Prior to developing the central theme of the paper, it will be useful to present the reader with an executive summary of the characteristics and mathematical relationships central to what is now commonly referred to as the standard model of Big Bang cosmology, the Friedmann-Lema^ıtre-Robertson-Walker metric. The Friedmann equations are analytic solutions of the Einstein field equations using the FLRW metric, and Equation(s) (1) show some commonly used forms that include the cosmological constant[1], Λ. -

Lesson 1: the Single Electron Atom: Hydrogen

Lesson 1: The Single Electron Atom: Hydrogen Irene K. Metz, Joseph W. Bennett, and Sara E. Mason (Dated: July 24, 2018) Learning Objectives: 1. Utilize quantum numbers and atomic radii information to create input files and run a single-electron calculation. 2. Learn how to read the log and report files to obtain atomic orbital information. 3. Plot the all-electron wavefunction to determine where the electron is likely to be posi- tioned relative to the nucleus. Before doing this exercise, be sure to read through the Ins and Outs of Operation document. So, what do we need to build an atom? Protons, neutrons, and electrons of course! But the mass of a proton is 1800 times greater than that of an electron. Therefore, based on de Broglie’s wave equation, the wavelength of an electron is larger when compared to that of a proton. In other words, the wave-like properties of an electron are important whereas we think of protons and neutrons as particle-like. The separation of the electron from the nucleus is called the Born-Oppenheimer approximation. So now we need the wave-like description of the Hydrogen electron. Hydrogen is the simplest atom on the periodic table and the most abundant element in the universe, and therefore the perfect starting point for atomic orbitals and energies. The compu- tational tool we are going to use is called OPIUM (silly name, right?). Before we get started, we should know what’s needed to create an input file, which OPIUM calls a parameter files. Each parameter file consist of a sequence of ”keyblocks”, containing sets of related parameters. -

A Young Physicist's Guide to the Higgs Boson

A Young Physicist’s Guide to the Higgs Boson Tel Aviv University Future Scientists – CERN Tour Presented by Stephen Sekula Associate Professor of Experimental Particle Physics SMU, Dallas, TX Programme ● You have a problem in your theory: (why do you need the Higgs Particle?) ● How to Make a Higgs Particle (One-at-a-Time) ● How to See a Higgs Particle (Without fooling yourself too much) ● A View from the Shadows: What are the New Questions? (An Epilogue) Stephen J. Sekula - SMU 2/44 You Have a Problem in Your Theory Credit for the ideas/example in this section goes to Prof. Daniel Stolarski (Carleton University) The Usual Explanation Usual Statement: “You need the Higgs Particle to explain mass.” 2 F=ma F=G m1 m2 /r Most of the mass of matter lies in the nucleus of the atom, and most of the mass of the nucleus arises from “binding energy” - the strength of the force that holds particles together to form nuclei imparts mass-energy to the nucleus (ala E = mc2). Corrected Statement: “You need the Higgs Particle to explain fundamental mass.” (e.g. the electron’s mass) E2=m2 c4+ p2 c2→( p=0)→ E=mc2 Stephen J. Sekula - SMU 4/44 Yes, the Higgs is important for mass, but let’s try this... ● No doubt, the Higgs particle plays a role in fundamental mass (I will come back to this point) ● But, as students who’ve been exposed to introductory physics (mechanics, electricity and magnetism) and some modern physics topics (quantum mechanics and special relativity) you are more familiar with.. -

Chapter 3 the Fundamentals of Nuclear Physics Outline Natural

Outline Chapter 3 The Fundamentals of Nuclear • Terms: activity, half life, average life • Nuclear disintegration schemes Physics • Parent-daughter relationships Radiation Dosimetry I • Activation of isotopes Text: H.E Johns and J.R. Cunningham, The physics of radiology, 4th ed. http://www.utoledo.edu/med/depts/radther Natural radioactivity Activity • Activity – number of disintegrations per unit time; • Particles inside a nucleus are in constant motion; directly proportional to the number of atoms can escape if acquire enough energy present • Most lighter atoms with Z<82 (lead) have at least N Average one stable isotope t / ta A N N0e lifetime • All atoms with Z > 82 are radioactive and t disintegrate until a stable isotope is formed ta= 1.44 th • Artificial radioactivity: nucleus can be made A N e0.693t / th A 2t / th unstable upon bombardment with neutrons, high 0 0 Half-life energy protons, etc. • Units: Bq = 1/s, Ci=3.7x 1010 Bq Activity Activity Emitted radiation 1 Example 1 Example 1A • A prostate implant has a half-life of 17 days. • A prostate implant has a half-life of 17 days. If the What percent of the dose is delivered in the first initial dose rate is 10cGy/h, what is the total dose day? N N delivered? t /th t 2 or e Dtotal D0tavg N0 N0 A. 0.5 A. 9 0.693t 0.693t B. 2 t /th 1/17 t 2 2 0.96 B. 29 D D e th dt D h e th C. 4 total 0 0 0.693 0.693t /th 0.6931/17 C. -

1 the LOCALIZED QUANTUM VACUUM FIELD D. Dragoman

1 THE LOCALIZED QUANTUM VACUUM FIELD D. Dragoman – Univ. Bucharest, Physics Dept., P.O. Box MG-11, 077125 Bucharest, Romania, e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT A model for the localized quantum vacuum is proposed in which the zero-point energy of the quantum electromagnetic field originates in energy- and momentum-conserving transitions of material systems from their ground state to an unstable state with negative energy. These transitions are accompanied by emissions and re-absorptions of real photons, which generate a localized quantum vacuum in the neighborhood of material systems. The model could help resolve the cosmological paradox associated to the zero-point energy of electromagnetic fields, while reclaiming quantum effects associated with quantum vacuum such as the Casimir effect and the Lamb shift; it also offers a new insight into the Zitterbewegung of material particles. 2 INTRODUCTION The zero-point energy (ZPE) of the quantum electromagnetic field is at the same time an indispensable concept of quantum field theory and a controversial issue (see [1] for an excellent review of the subject). The need of the ZPE has been recognized from the beginning of quantum theory of radiation, since only the inclusion of this term assures no first-order temperature-independent correction to the average energy of an oscillator in thermal equilibrium with blackbody radiation in the classical limit of high temperatures. A more rigorous introduction of the ZPE stems from the treatment of the electromagnetic radiation as an ensemble of harmonic quantum oscillators. Then, the total energy of the quantum electromagnetic field is given by E = åk,s hwk (nks +1/ 2) , where nks is the number of quantum oscillators (photons) in the (k,s) mode that propagate with wavevector k and frequency wk =| k | c = kc , and are characterized by the polarization index s. -

ANTIMATTER a Review of Its Role in the Universe and Its Applications

A review of its role in the ANTIMATTER universe and its applications THE DISCOVERY OF NATURE’S SYMMETRIES ntimatter plays an intrinsic role in our Aunderstanding of the subatomic world THE UNIVERSE THROUGH THE LOOKING-GLASS C.D. Anderson, Anderson, Emilio VisualSegrè Archives C.D. The beginning of the 20th century or vice versa, it absorbed or emitted saw a cascade of brilliant insights into quanta of electromagnetic radiation the nature of matter and energy. The of definite energy, giving rise to a first was Max Planck’s realisation that characteristic spectrum of bright or energy (in the form of electromagnetic dark lines at specific wavelengths. radiation i.e. light) had discrete values The Austrian physicist, Erwin – it was quantised. The second was Schrödinger laid down a more precise that energy and mass were equivalent, mathematical formulation of this as described by Einstein’s special behaviour based on wave theory and theory of relativity and his iconic probability – quantum mechanics. The first image of a positron track found in cosmic rays equation, E = mc2, where c is the The Schrödinger wave equation could speed of light in a vacuum; the theory predict the spectrum of the simplest or positron; when an electron also predicted that objects behave atom, hydrogen, which consists of met a positron, they would annihilate somewhat differently when moving a single electron orbiting a positive according to Einstein’s equation, proton. However, the spectrum generating two gamma rays in the featured additional lines that were not process. The concept of antimatter explained. In 1928, the British physicist was born. -

List of Particle Species-1

List of particle species that can be detected by Micro-Channel Plates and similar secondary electron multipliers. A Micro-Channel Plate (MCP) can detected certain particle species with decent quantum efficiency (QE). Commonly MCP are used to detect charged particles at low to intermediate energies and to register photons from VUV to X-ray energies. “Detection” means that a significant charge cloud is created in a channel (pore). Generally, a particle (or photon) can liberate an electron from channel surface atoms into the continuum if it carries sufficient momentum or if it can transfer sufficient potential energy. Therefore, fast-enough neutral atoms can also be detected by MCP and even exited atoms like He* (even when “slow”). At least about 10 eV of energy transfer is required to release an electron from the channel wall to start the avalanche. This number also determines the cut-off energy for photon detection which translates to a photon wave-length of about 200 nm (although there can be non- linear effects at extreme photon fluxes enhancing this cut-off wavelength). Not in all cases when ionization of a channel wall atom is possible, the electron will eventually be released to the continuum: the surface energy barrier has to be overcome and the electron must have the right emission direction. Also, the electron should be born close to surface because it may lose too much energy on its way out due to scattering and will be absorbed in the bulk. These effects reduce the QE at for VUV photons to about 10%. At EUV energies QE cannot improve much: although the primary electron energy increases, the ionization takes place deeper in the bulk on average and the electrons thus can hardly make it to the continuum. -

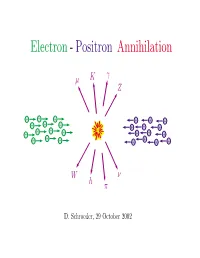

Electron - Positron Annihilation

Electron - Positron Annihilation γ µ K Z − − − + + + − − − + + + − − − − + + + − − − + + + + W ν h π D. Schroeder, 29 October 2002 OUTLINE • Electron-positron storage rings • Detectors • Reaction examples e+e− −→ e+e− [Inventory of known particles] e+e− −→ µ+µ− e+e− −→ q q¯ e+e− −→ W +W − • The future:Linear colliders Electron-Positron Colliders Hamburg Novosibirsk 11 GeV 12 GeV 47 GeV Geneva 200 GeV Ithaca Tokyo Stanford 12 GeV 64 GeV 8 GeV 12 GeV 30 GeV 100 GeV Beijing 12 GeV 4 GeV Size (R) and Cost ($) of an e+e− Storage Ring βE4 $=αR + ( E = beam energy) R d $ βE4 Find minimum $: 0= = α − dR R2 β =⇒ R = E2, $=2 αβ E2 α SPEAR: E = 8 GeV, R = 40 m, $ = 5 million LEP: E = 200 GeV, R = 4.3 km, $ = 1 billion + − + − Example 1: e e −→ e e e− total momentum = 0 θ − total energy = 2E e e+ Probability(E,θ)=? e+ E-dependence follows from dimensional analysis: density = ρ− A density = ρ+ − + × 2 Probability = (ρ− ρ+ − + A) (something with units of length ) ¯h ¯hc When E m , the only relevant length is = e p E 1 =⇒ Probability ∝ E2 at SPEAR Augustin, et al., PRL 34, 233 (1975) 6000 5000 4000 Ecm = 4.8 GeV 3000 2000 Number of Counts 1000 Theory 0 −0.8 −0.40 0.40.8 cos θ Prediction for e+e− −→ e+e− event rate (H. J. Bhabha, 1935): event dσ e4 1 + cos4 θ 2 cos4 θ 1 + cos2 θ ∝ = 2 − 2 + rate dΩ 32π2E2 4 θ 2 θ 2 cm sin 2 sin 2 Interpretation of Bhabha’sformula (R.