GLAST Science Glossary (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

2. Astrophysical Constants and Parameters

2. Astrophysical constants 1 2. ASTROPHYSICAL CONSTANTS AND PARAMETERS Table 2.1. Revised May 2010 by E. Bergren and D.E. Groom (LBNL). The figures in parentheses after some values give the one standard deviation uncertainties in the last digit(s). Physical constants are from Ref. 1. While every effort has been made to obtain the most accurate current values of the listed quantities, the table does not represent a critical review or adjustment of the constants, and is not intended as a primary reference. The values and uncertainties for the cosmological parameters depend on the exact data sets, priors, and basis parameters used in the fit. Many of the parameters reported in this table are derived parameters or have non-Gaussian likelihoods. The quoted errors may be highly correlated with those of other parameters, so care must be taken in propagating them. Unless otherwise specified, cosmological parameters are best fits of a spatially-flat ΛCDM cosmology with a power-law initial spectrum to 5-year WMAP data alone [2]. For more information see Ref. 3 and the original papers. Quantity Symbol, equation Value Reference, footnote speed of light c 299 792 458 m s−1 exact[4] −11 3 −1 −2 Newtonian gravitational constant GN 6.674 3(7) × 10 m kg s [1] 19 2 Planck mass c/GN 1.220 89(6) × 10 GeV/c [1] −8 =2.176 44(11) × 10 kg 3 −35 Planck length GN /c 1.616 25(8) × 10 m[1] −2 2 standard gravitational acceleration gN 9.806 65 m s ≈ π exact[1] jansky (flux density) Jy 10−26 Wm−2 Hz−1 definition tropical year (equinox to equinox) (2011) yr 31 556 925.2s≈ π × 107 s[5] sidereal year (fixed star to fixed star) (2011) 31 558 149.8s≈ π × 107 s[5] mean sidereal day (2011) (time between vernal equinox transits) 23h 56m 04.s090 53 [5] astronomical unit au, A 149 597 870 700(3) m [6] parsec (1 au/1 arc sec) pc 3.085 677 6 × 1016 m = 3.262 ...ly [7] light year (deprecated unit) ly 0.306 6 .. -

Light and Illumination

ChapterChapter 3333 -- LightLight andand IlluminationIllumination AAA PowerPointPowerPointPowerPoint PresentationPresentationPresentation bybyby PaulPaulPaul E.E.E. Tippens,Tippens,Tippens, ProfessorProfessorProfessor ofofof PhysicsPhysicsPhysics SouthernSouthernSouthern PolytechnicPolytechnicPolytechnic StateStateState UniversityUniversityUniversity © 2007 Objectives:Objectives: AfterAfter completingcompleting thisthis module,module, youyou shouldshould bebe ableable to:to: •• DefineDefine lightlight,, discussdiscuss itsits properties,properties, andand givegive thethe rangerange ofof wavelengthswavelengths forfor visiblevisible spectrum.spectrum. •• ApplyApply thethe relationshiprelationship betweenbetween frequenciesfrequencies andand wavelengthswavelengths forfor opticaloptical waves.waves. •• DefineDefine andand applyapply thethe conceptsconcepts ofof luminousluminous fluxflux,, luminousluminous intensityintensity,, andand illuminationillumination.. •• SolveSolve problemsproblems similarsimilar toto thosethose presentedpresented inin thisthis module.module. AA BeginningBeginning DefinitionDefinition AllAll objectsobjects areare emittingemitting andand absorbingabsorbing EMEM radiaradia-- tiontion.. ConsiderConsider aa pokerpoker placedplaced inin aa fire.fire. AsAs heatingheating occurs,occurs, thethe 1 emittedemitted EMEM waveswaves havehave 2 higherhigher energyenergy andand 3 eventuallyeventually becomebecome visible.visible. 4 FirstFirst redred .. .. .. thenthen white.white. LightLightLight maymaymay bebebe defineddefineddefined -

Lecture 3 - Minimum Mass Model of Solar Nebula

Lecture 3 - Minimum mass model of solar nebula o Topics to be covered: o Composition and condensation o Surface density profile o Minimum mass of solar nebula PY4A01 Solar System Science Minimum Mass Solar Nebula (MMSN) o MMSN is not a nebula, but a protoplanetary disc. Protoplanetary disk Nebula o Gives minimum mass of solid material to build the 8 planets. PY4A01 Solar System Science Minimum mass of the solar nebula o Can make approximation of minimum amount of solar nebula material that must have been present to form planets. Know: 1. Current masses, composition, location and radii of the planets. 2. Cosmic elemental abundances. 3. Condensation temperatures of material. o Given % of material that condenses, can calculate minimum mass of original nebula from which the planets formed. • Figure from Page 115 of “Physics & Chemistry of the Solar System” by Lewis o Steps 1-8: metals & rock, steps 9-13: ices PY4A01 Solar System Science Nebula composition o Assume solar/cosmic abundances: Representative Main nebular Fraction of elements Low-T material nebular mass H, He Gas 98.4 % H2, He C, N, O Volatiles (ices) 1.2 % H2O, CH4, NH3 Si, Mg, Fe Refractories 0.3 % (metals, silicates) PY4A01 Solar System Science Minimum mass for terrestrial planets o Mercury:~5.43 g cm-3 => complete condensation of Fe (~0.285% Mnebula). 0.285% Mnebula = 100 % Mmercury => Mnebula = (100/ 0.285) Mmercury = 350 Mmercury o Venus: ~5.24 g cm-3 => condensation from Fe and silicates (~0.37% Mnebula). =>(100% / 0.37% ) Mvenus = 270 Mvenus o Earth/Mars: 0.43% of material condensed at cooler temperatures. -

1.1. Introduction the Phenomenon of Positron Annihilation Spectroscopy

PRINCIPLES OF POSITRON ANNIHILATION Chapter-1 __________________________________________________________________________________________ 1.1. Introduction The phenomenon of positron annihilation spectroscopy (PAS) has been utilized as nuclear method to probe a variety of material properties as well as to research problems in solid state physics. The field of solid state investigation with positrons started in the early fifties, when it was recognized that information could be obtained about the properties of solids by studying the annihilation of a positron and an electron as given by Dumond et al. [1] and Bendetti and Roichings [2]. In particular, the discovery of the interaction of positrons with defects in crystal solids by Mckenize et al. [3] has given a strong impetus to a further elaboration of the PAS. Currently, PAS is amongst the best nuclear methods, and its most recent developments are documented in the proceedings of the latest positron annihilation conferences [4-8]. PAS is successfully applied for the investigation of electron characteristics and defect structures present in materials, magnetic structures of solids, plastic deformation at low and high temperature, and phase transformations in alloys, semiconductors, polymers, porous material, etc. Its applications extend from advanced problems of solid state physics and materials science to industrial use. It is also widely used in chemistry, biology, and medicine (e.g. locating tumors). As the process of measurement does not mostly influence the properties of the investigated sample, PAS is a non-destructive testing approach that allows the subsequent study of a sample by other methods. As experimental equipment for many applications, PAS is commercially produced and is relatively cheap, thus, increasingly more research laboratories are using PAS for basic research, diagnostics of machine parts working in hard conditions, and for characterization of high-tech materials. -

Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram

Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram Astronomers have made surveys of the temperatures and luminosities of stars and plot the result on H-R (or Temperature-Luminosity) diagrams. Many stars fall on a diagonal line running from the upper left (hot and luminous) to the lower right (cool and faint). The Sun is one of these stars. But some fall in the upper right (cool and luminous) and some fall toward the bottom of the diagram (faint). What can we say about the stars in the upper right? What can we say about the stars toward the bottom? If all stars had the same size, what pattern would they make on the diagram? Masses of Stars The gravitational force of the Sun keeps the planets in orbit around it. The force of the Sun’s gravity is proportional to the mass of the Sun, and so the speeds of the planets as they orbit the Sun depend on the mass of the Sun. Newton’s generalization of Kepler’s 3rd law says: P2 = a3 / M where P is the time to orbit, measured in years, a is the size of the orbit, measured in AU, and M is the sum of the two masses, measured in solar masses. Masses of stars It is difficult to see planets orbiting other stars, but we can see stars orbiting other stars. By measuring the periods and sizes of the orbits we can calculate the masses of the stars. If P2 = a3 / M, M = a3 / P2 This mass in the formula is actually the sum of the masses of the two stars. -

25 Geometric Optics

CHAPTER 25 | GEOMETRIC OPTICS 887 25 GEOMETRIC OPTICS Figure 25.1 Image seen as a result of reflection of light on a plane smooth surface. (credit: NASA Goddard Photo and Video, via Flickr) Learning Objectives 25.1. The Ray Aspect of Light • List the ways by which light travels from a source to another location. 25.2. The Law of Reflection • Explain reflection of light from polished and rough surfaces. 25.3. The Law of Refraction • Determine the index of refraction, given the speed of light in a medium. 25.4. Total Internal Reflection • Explain the phenomenon of total internal reflection. • Describe the workings and uses of fiber optics. • Analyze the reason for the sparkle of diamonds. 25.5. Dispersion: The Rainbow and Prisms • Explain the phenomenon of dispersion and discuss its advantages and disadvantages. 25.6. Image Formation by Lenses • List the rules for ray tracking for thin lenses. • Illustrate the formation of images using the technique of ray tracking. • Determine power of a lens given the focal length. 25.7. Image Formation by Mirrors • Illustrate image formation in a flat mirror. • Explain with ray diagrams the formation of an image using spherical mirrors. • Determine focal length and magnification given radius of curvature, distance of object and image. Introduction to Geometric Optics Geometric Optics Light from this page or screen is formed into an image by the lens of your eye, much as the lens of the camera that made this photograph. Mirrors, like lenses, can also form images that in turn are captured by your eye. 888 CHAPTER 25 | GEOMETRIC OPTICS Our lives are filled with light. -

Black Body Radiation and Radiometric Parameters

Black Body Radiation and Radiometric Parameters: All materials absorb and emit radiation to some extent. A blackbody is an idealization of how materials emit and absorb radiation. It can be used as a reference for real source properties. An ideal blackbody absorbs all incident radiation and does not reflect. This is true at all wavelengths and angles of incidence. Thermodynamic principals dictates that the BB must also radiate at all ’s and angles. The basic properties of a BB can be summarized as: 1. Perfect absorber/emitter at all ’s and angles of emission/incidence. Cavity BB 2. The total radiant energy emitted is only a function of the BB temperature. 3. Emits the maximum possible radiant energy from a body at a given temperature. 4. The BB radiation field does not depend on the shape of the cavity. The radiation field must be homogeneous and isotropic. T If the radiation going from a BB of one shape to another (both at the same T) were different it would cause a cooling or heating of one or the other cavity. This would violate the 1st Law of Thermodynamics. T T A B Radiometric Parameters: 1. Solid Angle dA d r 2 where dA is the surface area of a segment of a sphere surrounding a point. r d A r is the distance from the point on the source to the sphere. The solid angle looks like a cone with a spherical cap. z r d r r sind y r sin x An element of area of a sphere 2 dA rsin d d Therefore dd sin d The full solid angle surrounding a point source is: 2 dd sind 00 2cos 0 4 Or integrating to other angles < : 21cos The unit of solid angle is steradian. -

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2 February 15, 2006 . DRAFT Cambridge-MIT Institute Multidisciplinary Design Project This Dictionary/Glossary of Engineering terms has been compiled to compliment the work developed as part of the Multi-disciplinary Design Project (MDP), which is a programme to develop teaching material and kits to aid the running of mechtronics projects in Universities and Schools. The project is being carried out with support from the Cambridge-MIT Institute undergraduate teaching programe. For more information about the project please visit the MDP website at http://www-mdp.eng.cam.ac.uk or contact Dr. Peter Long Prof. Alex Slocum Cambridge University Engineering Department Massachusetts Institute of Technology Trumpington Street, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Cambridge. Cambridge MA 02139-4307 CB2 1PZ. USA e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] tel: +44 (0) 1223 332779 tel: +1 617 253 0012 For information about the CMI initiative please see Cambridge-MIT Institute website :- http://www.cambridge-mit.org CMI CMI, University of Cambridge Massachusetts Institute of Technology 10 Miller’s Yard, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Mill Lane, Cambridge MA 02139-4307 Cambridge. CB2 1RQ. USA tel: +44 (0) 1223 327207 tel. +1 617 253 7732 fax: +44 (0) 1223 765891 fax. +1 617 258 8539 . DRAFT 2 CMI-MDP Programme 1 Introduction This dictionary/glossary has not been developed as a definative work but as a useful reference book for engi- neering students to search when looking for the meaning of a word/phrase. It has been compiled from a number of existing glossaries together with a number of local additions. -

9.2 Refraction and Total Internal Reflection

9.2 refraction and total internal reflection When a light wave strikes a transparent material such as glass or water, some of the light is reflected from the surface (as described in Section 9.1). The rest of the light passes through (transmits) the material. Figure 1 shows a ray that has entered a glass block that has two parallel sides. The part of the original ray that travels into the glass is called the refracted ray, and the part of the original ray that is reflected is called the reflected ray. normal incident ray reflected ray i r r ϭ i air glass 2 refracted ray Figure 1 A light ray that strikes a glass surface is both reflected and refracted. Refracted and reflected rays of light account for many things that we encounter in our everyday lives. For example, the water in a pool can look shallower than it really is. A stick can look as if it bends at the point where it enters the water. On a hot day, the road ahead can appear to have a puddle of water, which turns out to be a mirage. These effects are all caused by the refraction and reflection of light. refraction The direction of the refracted ray is different from the direction of the incident refraction the bending of light as it ray, an effect called refraction. As with reflection, you can measure the direction of travels at an angle from one medium the refracted ray using the angle that it makes with the normal. In Figure 1, this to another angle is labelled θ2. -

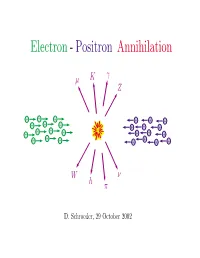

Electron - Positron Annihilation

Electron - Positron Annihilation γ µ K Z − − − + + + − − − + + + − − − − + + + − − − + + + + W ν h π D. Schroeder, 29 October 2002 OUTLINE • Electron-positron storage rings • Detectors • Reaction examples e+e− −→ e+e− [Inventory of known particles] e+e− −→ µ+µ− e+e− −→ q q¯ e+e− −→ W +W − • The future:Linear colliders Electron-Positron Colliders Hamburg Novosibirsk 11 GeV 12 GeV 47 GeV Geneva 200 GeV Ithaca Tokyo Stanford 12 GeV 64 GeV 8 GeV 12 GeV 30 GeV 100 GeV Beijing 12 GeV 4 GeV Size (R) and Cost ($) of an e+e− Storage Ring βE4 $=αR + ( E = beam energy) R d $ βE4 Find minimum $: 0= = α − dR R2 β =⇒ R = E2, $=2 αβ E2 α SPEAR: E = 8 GeV, R = 40 m, $ = 5 million LEP: E = 200 GeV, R = 4.3 km, $ = 1 billion + − + − Example 1: e e −→ e e e− total momentum = 0 θ − total energy = 2E e e+ Probability(E,θ)=? e+ E-dependence follows from dimensional analysis: density = ρ− A density = ρ+ − + × 2 Probability = (ρ− ρ+ − + A) (something with units of length ) ¯h ¯hc When E m , the only relevant length is = e p E 1 =⇒ Probability ∝ E2 at SPEAR Augustin, et al., PRL 34, 233 (1975) 6000 5000 4000 Ecm = 4.8 GeV 3000 2000 Number of Counts 1000 Theory 0 −0.8 −0.40 0.40.8 cos θ Prediction for e+e− −→ e+e− event rate (H. J. Bhabha, 1935): event dσ e4 1 + cos4 θ 2 cos4 θ 1 + cos2 θ ∝ = 2 − 2 + rate dΩ 32π2E2 4 θ 2 θ 2 cm sin 2 sin 2 Interpretation of Bhabha’sformula (R. -

QCD at Colliders

Particle Physics Dr Victoria Martin, Spring Semester 2012 Lecture 10: QCD at Colliders !Renormalisation in QCD !Asymptotic Freedom and Confinement in QCD !Lepton and Hadron Colliders !R = (e+e!!hadrons)/(e+e!"µ+µ!) !Measuring Jets !Fragmentation 1 From Last Lecture: QCD Summary • QCD: Quantum Chromodymanics is the quantum description of the strong force. • Gluons are the propagators of the QCD and carry colour and anti-colour, described by 8 Gell-Mann matrices, !. • For M calculate the appropriate colour factor from the ! matrices. 2 2 • The coupling constant #S is large at small q (confinement) and large at high q (asymptotic freedom). • Mesons and baryons are held together by QCD. • In high energy collisions, jets are the signatures of quark and gluon production. 2 Gluon self-Interactions and Confinement , Gluon self-interactions are believed to give e+ q rise to colour confinement , Qualitative picture: •Compare QED with QCD •In QCD “gluon self-interactions squeeze lines of force into Gluona flux tube self-Interactions” ande- Confinementq , + , What happens whenGluon try self-interactions to separate two are believedcoloured to giveobjects e.g. qqe q rise to colour confinement , Qualitativeq picture: q •Compare QED with QCD •In QCD “gluon self-interactions squeeze lines of force into a flux tube” e- q •Form a flux tube, What of happensinteracting when gluons try to separate of approximately two coloured constant objects e.g. qq energy density q q •Require infinite energy to separate coloured objects to infinity •Form a flux tube of interacting gluons of approximately constant •Coloured quarks and gluons are always confined within colourless states energy density •In this way QCD provides a plausible explanation of confinement – but not yet proven (although there has been recent progress with Lattice QCD) Prof.