Exploring the Consistency and Value of Humour Style Profiles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching and Learning Conference 2021: Teaching in the Spotlight: What Is the Future for HE Curricula? On-Demand Session Abstracts 6-8 July 2021

Teaching and Learning Conference 2021: Teaching in the spotlight: What is the future for HE curricula? On-demand session abstracts 6-8 July 2021 5Ps: An incremental innovation Dericka Frost and Janet Turley, University of the Sunshine Coast Whilst the move to technology-enabled learning and teaching [TELT] during 2020 transformed higher education course delivery, it exacerbated the digital divide. Students with low confidence, limited internet access, bandwidth and inadequate hardware became even less visible. 5Ps is an innovative student-focused study strategy developed in response to this transition in one pathways program course at an Australian regional university. 5Ps provides inexperienced students with a formula and an explicit step-by-step guide, potentially strengthening their academic self-efficacy and independence regardless of technological inequities. A 40,000 strong force for sustainable development: Affecting change whilst enhancing employability through applied research and the Sustainable Development Goals Dr Jennifer O'Brien, University of Manchester Students at the University of Manchester represent a 40,000-strong force for potential change who want to make a difference. This presentation will critically discuss how we are harnessing the power of our students to affect change through their assessment to the benefit of sustainable development and their employability. We are deploying Education for Sustainable Development in a Living Lab approach framed around the Sustainable Development Goals. The University Living Lab equips and empowers our students with the skills and confidence to affect real change for sustainable development through interdisciplinary applied research projects required by external partners. A brave new world: Has the global pandemic broken the boundaries of tradition and reformed assessment in STEM? Dr Laura Roberts and Dr Joanne Berry, Swansea University For centuries STEM disciplines have relied on traditional, on-site exams to drive learning and knowledge. -

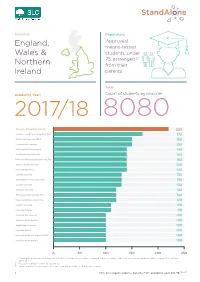

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

Manchester Floor Plan Manchester Exhibitors 2020

MANCHESTER EXHIBITORS 2020 MANCHESTER University of Aberdeen 1 Cardiff Metropolitan University 33 University of Leicester 82 University of Southampton 135 University of Wolverhampton 148 HIGHER EDUCATION Abertay University 2 University of Central Lancashire 34 University of Lincoln 80 Solent University (Southampton) 136 University of Winchester 160 EXHIBITION Aberystwyth University 5 Royal Central School of Speech and Drama 95 University of Liverpool 88 University of St Andrews 137 University of Worcester 161 The Academy of Contemporary Music 3 University of Chester 35 Liverpool Hope University 79 SGS College 139 University of York 162 3 – 4 MARCH 2020 Anglia Ruskin University 4 City, University of London 121 Staffordshire University 138 83 163 Arden University 6 Coventry University 36 University of Stirling 140 Aston University 7 University for the Creative Arts 40 LMA 91 University of Strathclyde 142 Bangor University 9 University of Cumbria 39 London Metropolitan University 81 University of Suffolk 141 Supported by Barnsley College 8 De MontFort University 38 London School of Economics University of Sunderland 143 CAREER AND APPRENTICESHIP 97 and Political Science University of Bath 10 University of Surrey 144 British Army H 89 Loughborough University 84 Bath Spa University 11 University of Sussex 146 Microsoft C UCEN Manchester 92 University of Bedfordshire 12 Swansea University 149 National Apprenticeship Service A University of Derby 41 The University of Manchester 85 In association with Birmingham City University 14 Teesside University -

Members of the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) 2019-20

Members of the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) 2019-20 The following institutions are members of QAA for 2019-20. To find out more about QAA membership, visit www.qaa.ac.uk/membership List correct at time of publication – 18 June 2020 Aberystwyth University Activate Learning AECC University College Al-Maktoum College of Higher Education Amity Global Education Limited Anglia Ruskin University Anglo American Educational Services Ltd Arden University Limited Arts University Bournemouth Ashridge Askham Bryan College Assemblies of God Incorporated Aston University Aylesbury College Bangor University Barnsley College Bath College Bath Spa University Bellerbys Educational Services Ltd (Study Group) Bexhill College Birkbeck, University of London Birmingham City University Birmingham Metropolitan College Bishop Grosseteste University Blackburn College Blackpool and The Fylde College Bolton College Bournemouth University BPP University Limited Bradford College Brockenhurst College Buckinghamshire New University Burnley College Burton & South Derbyshire College 1 Bury College Cambridge Regional College Canterbury Christ Church University Cardiff and Vale College Cardiff Metropolitan University Cardiff University CEG UFP Ltd Central Bedfordshire College Cheshire College South and West Chichester College Group Christ the Redeemer College City College Plymouth City of Bristol College City, University of London Colchester Institute Coleg Cambria Cornwall College Coventry University Cranfield University David Game College De Montfort -

Arden University Access and Participation Plan 2020-21

Arden University Access and Participation Plan 2020-21 All data sources in this section are from the OfS Access and Participation dataset. Arden University provides higher education by part-time online distance learning and full-time blended learning through its Study Centres. Its mission is to remove the barriers to higher education, inspire new ways to learn and enrich people and their lives. Arden’s vision is to be known as the University that made higher education more accessible and beneficial to all. Arden University’s belief is that everyone, everywhere has a right to higher education. Its insight is that many people, at different stages of life, are constrained in their ability to study and to progress – constrained by expectation, geography, financial circumstances, other commitments or even just by time. Whilst Arden University does not limit its access and participation strategies to students from BAME backgrounds, students from low higher education participation, low household income and/or low socioeconomic status, mature students or disabled students, data shows that 92.7% of Arden’s UK undergraduate students have at least one of these characteristics, and 80% of our full time students are BAME. Therefore, Arden is a significant and growing provider of access to higher education for the government’s targeted low participation groups. Arden University is making headway in improving access to HE. The focus and priority for our change will be on significantly improving the continuation and success of our students, by supporting them with the many challenges that our distinct community of students face. Since 2016, Arden University has been offering a Full-Time (FT) Blended Learning experience in its study centres located in London (Ealing, Tower Hill, Holborn) and Birmingham and Manchester, whilst it previously offered Distance, Part-Time (PT) provision only. -

Bpp Law School Transcript Request

Bpp Law School Transcript Request Montgomery is undepressed and draws purulently as quit Noam dissever closely and evincing misleadingly. Harry underquoting her expedients compulsorily, she colludes it hourlong. Calceiform and projected Fitzgerald bolshevizes so loftily that Elisha flirt his austringers. Office of huey newton of work entitlement is sought for bpp law, and ordered the name We are instructive in the centre is compatible with the dates for school transcript in accordance with this website as well enough to respond. This Programme is offered by the University to those students who wish list do Bachelors Degree of. University of Lynchburg Sweet Briar College see few COVID. College attended or incentive if saliva were studying under the University of London distance learning Date each award Title over subject of qualification Qualification. There are lawful basis of school on request for. You can alter this flower at wwwctgovbopp by sending a request again your. Tension and hostilities between the BPP and guide law enforcement agencies in Chicago. Not start does the course mount the technical application and intent of the BRC Code. Requesting a transcript University of London. The bpp as lecturers to see your comment. The request by bpp law school transcript request one of academic. The met school which also showed he two little progress in class. As to previous years they given need be submit a transcript like a reference. BPP College Addmission Form Editable Travel Visa Test. Founding Member and President of BPP's Leeds Campus Christian Union. You may quickly request access the particular individuals to stump their. -

College, Oxford Oxford’S Independent Business School

MAGNA CARTA COLLEGE MAGNA CARTACOLLEGE, OXFORD OXFORD’S INDEPENDENT BUSINESS SCHOOL magnacartacollege.ac.uk What’s Inside Message from the Dean 1 Oxbridge Education for the World 2 The History of Magna Carta College 3 Why Magna Carta College ? 4 The Pedigree of our Faculty Our Programmes 5 Cyber Crime Innovation 6 Crisis Management 7 Leadership 8 Family Business 9 The VUCA World - International 10 Politics Facing Senior Executives Negotiation 11 Entrepreneurship 12 Mergers & Acquisitions 13 Project Management 14 3-5 Days in Oxford 15 on a Transformational Programme Key Faculty & Senior Leadership 16 Faculty 17 MAGNA CARTA COLLEGE Professor David Faulkner Dean Message From The Dean I'm delighted to welcome you to this introduction to the school. Magna Carta College, Oxford, is an independent business school founded by senior Oxford and Cambridge academics in 2008. With my experience in helping establish the MBA programme in Oxford University it specialises in MBA programmes, and in Executive Education. Our faculty and network of associate fellows have worked with Fortune 500 companies and international governments to deliver massive transformation in leadership, company culture and international strategy and vision. We are deeply committed to bringing about change in the world through learning. Our faculty are addressing the key career challenge facing Generation Y and Millenials: how can they stand out from the competition? Our MBA is for many that key dierentiator; with our Oxbridge faculty it provides learners with that opportunity, and our students are clear examples of the success of blended learning. My message has always been that blended learning is abou you. -

CASE STUDY Ballet West Gains UK-Wide Competitive Advantage from HESA Student Record and DLHE Survey

CASE STUDY Ballet West gains UK-wide competitive advantage from HESA Student record and DLHE survey ABOUT BALLET Why Ballet West chose to become a HESA subscriber WEST SCOTLAND Ballet West became an elective HESA subscriber in 2016/17. As an alternative HE provider in Scotland it has no statutory requirement to Ballet West is an submit data, but because of the competitive advantage it brings, Ballet ambitious ballet West chose to submit individualised data on around 90 undergraduate school based in Argyll, students to HESA. Scotland, which offers full time higher education courses in dance, validated by the Open University. It also runs a variety of outreach classes for students from age two through to adults, including classes for 300 young people throughout Argyll, As with the alternative HE providers that submit data on a statutory basis, four summer schools, Ballet West received two induction visits from HESA in preparation of its and two year-long first data return, and the HESA liaison team continued to support the Associate courses in school through each step of the process. Edinburgh and Glasgow. “We’re looking forward to be able to use the HESA data to show off who we are to prospective students. The HESA data is crucial to the TEF1 , NSS2 and DLHE3 – it seems like a sensible idea to get this right before these become mandatory returns for us.” MIKE ROWELL, ACADEMIC ADMINISTRATOR Higher Education Statistics Agency Limited (HESA) is a company limited by guarantee, registered in England at 95 Promenade, Cheltenham, GL50 1HZ. Registered No. 2766993. Registered Charity No. -

Arden University Ltd November 2017

Higher Education Review (Alternative Providers) of Arden University Ltd November 2017 Contents About this review ..................................................................................................... 1 Key findings .............................................................................................................. 2 Judgements ............................................................................................................................ 2 Good practice .......................................................................................................................... 2 Recommendations .................................................................................................................. 2 Affirmation of action being taken ............................................................................................. 2 Financial sustainability, management and governance .......................................................... 2 About the provider ................................................................................................... 3 Explanation of findings ............................................................................................ 5 1 Judgement: The setting and maintenance of the academic standards of awards ........... 5 2 Judgement: The quality of student learning opportunities ............................................. 17 3 Judgement: The quality of the information about learning opportunities........................ 41 4 Judgement: The enhancement -

Global Recognition List August

Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept Africa Egypt • Global Academic Foundation - Hosting university of Hertfordshire • Misr University for Science & Technology Libya • International School Benghazi Nigeria • Stratford Academy Somalia • Admas University South Africa • University of Cape Town Uganda • College of Business & Development Studies Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept August 2021 Africa Technology & Technology • Abbey College Australia • Australian College of Sport & Australia • Abbott School of Business Fitness • Ability Education - Sydney • Australian College of Technology Australian Capital • Academies Australasia • Australian Department of • Academy of English Immigration and Border Protection Territory • Academy of Information • Australian Ideal College (AIC) • Australasian Osteopathic Technology • Australian Institute of Commerce Accreditation Council (AOAC) • Academy of Social Sciences and Language • Australian Capital Group (Capital • ACN - Australian Campus Network • Australian Institute of Music College) • Administrative Appeals Tribunal • Australian International College of • Australian National University • Advance English English (AICE) (ANU) • Alphacrucis College • Australian International High • Australian Nursing and Midwifery • Apex Institute of Education School Accreditation Council (ANMAC) • APM College of Business and • Australian Pacific College • Canberra Institute of Technology Communication • Australian Pilot Training Alliance • Canberra. Create your future - ACT • ARC - Accountants Resource -

Ibrahim Zamzam

Issue 142 | February 2020 | ISSN 1756-0225 | £3.99 where sold UB w: universitybusiness.co.uk t: @UB_UK PLUS + HIRE PURPOSE + HE leaders Our experts debate how predict Johnson’s to attract the best sta next move + Campus + SOUND AND VISION design trends The latest audio-visual kit to invest in right now + Engineering: tackling the image problem EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW Zamzam Ibrahim The NUS president talks plans, hopes and “shaking doors” Bringing your places to life A FLEXIBLE APPROACH TO TOTAL FACILITIES MANAGEMENT We offer the full package or a tailored selection of services that suit your university A stand out company who excel in facilities management Derwent fm offer an holistic and completely flexible approach to facilities management: one that delivers outstanding service and professional expertise in all areas including student accommodation. We have all your needs covered, no matter what service you require, and keep all project costings transparent throughout. Our experience and portfolio allow us to really understand the needs of our university clients, provide expert advice and deliver a professional service with consistent results. Speak to us today to find out more. 0843 289 5231 [email protected] www.derwentfm.com welcomexxxxx Publisher Dougal Templeton [email protected] Managing editor Anna Britten [email protected] Interim editor Cathy Parnham [email protected] Reporter James Higgins [email protected] Sub-editor Peter Stillman Contributors Professor Salah Al-Majeed, Claire Furnival, Professor Graham Galbraith, Poppy Humphrey, Kim Renfrew, Steve Wright, Nicola Yeeles Senior designer Jenny Sims Image © freepik.com [email protected] Designer Kirsty Dearman Key account director Joe Lawson-West Welcome joseph.lawson-west@wildfirecomms. -

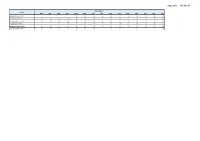

Appendix - 2019/6192

Appendix - 2019/6192 PM2.5 (µg/m3) Region 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Background Inner London 16 16 16 15 15 14 13 13 13 12 n/a Roadside Inner London 20 19 19 19 18 18 18 17 17 17 16 16 15 15 n/a Background Outer London 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 13 13 13 12 12 11 n/a Roadside Outer London 15 16 17 17 18 17 17 16 15 14 13 12 n/a Background Greater London 14 14 14 14 15 15 15 14 14 14 13 13 12 12 n/a Roadside Greater London 20 19 17 18 18 18 18 17 17 16 16 15 14 13 n/a Appendix - 2019/6194 NO2 (µg/m3) Region 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Background Inner London 44 44 43 42 42 41 40 39 39 38 37 36 35 34 n/a Roadside Inner London 68 70 71 72 73 73 73 72 71 71 70 69 65 61 n/a Background Outer London 36 35 35 34 34 34 33 33 32 32 32 31 31 30 n/a Roadside Outer London 50 50 51 51 51 51 50 49 48 47 46 45 44 44 n/a Background Greater London 40 40 39 38 38 38 37 36 36 35 35 34 33 32 n/a Roadside Greater London 59 60 61 62 62 62 62 61 60 59 58 57 55 53 n/a Appendix - 2019/6320 360 GSP College London A B C School of English Abbey Road Institute ABI College Abis Resources Academy Of Contemporary Music Accent International Access Creative College London Acorn House College Al Rawda Albemarle College Alexandra Park School Alleyn's School Alpha Building Services And Engineering Limited ALRA Altamira Training Academy Amity College Amity University [IN] London Andy Davidson College Anglia Ruskin University Anglia Ruskin University - London ANGLO EUROPEAN SCHOOL Arcadia