The Camouflage of the Sacred in the Short Fiction of Hemingway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And a River Went out of Eden| the Estuarial Motif in Hemingway's "The Garden of Eden"

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1994 And a river went out of Eden| The estuarial motif in Hemingway's "The Garden of Eden" Howard A. Schmid The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Schmid, Howard A., "And a river went out of Eden| The estuarial motif in Hemingway's "The Garden of Eden"" (1994). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1560. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1560 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY TheMontana University of Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes " or "No " and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature Date: ^ ^ j°\ Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the nnthnr'c pyniioit- AND A RIVER WENT OUT OF EDEN The Estuarial Motif in Hemingway's The Garden of Eden by Howard A. (Hal) Schmid B.A., University of Oregon, 1976 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana 1994 Approved by: Chairperson E€an, Graduate School ? tr Date T UMI Number: EP34014 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. -

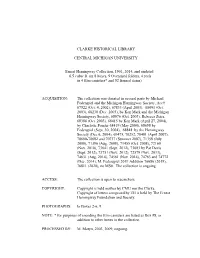

Box and Folder Listing

CLARKE HISTORICAL LIBRARY CENTRAL MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY Ernest Hemingway Collection, 1901, 2006, and undated 5 cubic ft. (in 3 boxes, 6 Oversized folders, 4 reels in 4 boxes, and 2 framed posters) ACQUISITION: The collection was donated in several parts by Michael Federspiel and the Michigan Hemingway Society, Acc# 67522 (Oct. 4, 2002), #67833 (April 2003), Acc# 68091 (Oct. 2003), Acc#68230 (Dec. 2003), by Ken Mark and the Michigan Hemingway Society, Acc#68076 (Oct. 2003), Rebecca Zeiss, Acc# 68386 (Oct. 2003), Acc#68415 by Ken Mark (April 27, 2004), by Charlotte Ponder Acc# 68419 (May 2004), Acc#68698 by Federspiel (Sept. 30, 2004), Acc#68848 by the Hemingway Society (Dec.6, 2004), Acc#69475, Acc#70252, Acc#70401 (April 2007), Acc#70680-70682 and 70737 (Summer 2007), 70833 (March 2008), no MS#. The collection is ongoing. ACCESS: The collection is open to researchers. COPYRIGHT: Copyright is held neither by CMU nor the Clarke. PHOTOGRAPHS: In Box 2. PROCESSED BY: M. Matyn, Feb., Oct. and April 2003, March-May 2004, Feb. 2006, April and June 2007, Jan. and March 2008. Biography: Ernest Hemingway was born July 21, 1899 in Oak Park (Ill.), the son of Clarence E. Hemingway, a doctor, and Grace Hall-Hemingway, a musician and voice teacher. He had four sisters and a brother. Every summer, the family summered at the family cottage, named Windemere, on Walloon Lake near Petoskey (Mich.). After Ernest graduated from high school in June 1917, he joined the Missouri Home Guard. Before it was called to active duty, he served as a volunteer ambulance driver for the American Red Cross. -

Open HONORS FINAL.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER’S HONORS COLLEGE DIVISION OF ARTS AND HUMANITIES MENTAL ILLNESS IN FAMILY MEMOIRS: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDY EXAMINING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MENTALLY ILL PARENTS AND THEIR CHILDREN BRANDON CHERRY SPRING 2016 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in Letters, Arts, and Sciences Reviewed and approved* by the following: Ellen Knodt Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Karen Weekes Associate Professor of English and Women’s Studies Faculty Reader *Signatures are on file in the Schreyer’s Honors College. i Abstract This project explores the relationship between mentally ill parents and their children in the memoir form. These family memoirs offer insights into the effects of mentally ill parents on their children. The family memoirs of three famous twentieth century writers are studied to analyze the effects of mental illness in the written form, because a wide majority of the population does not have the privilege or skills to write about events effectively. Further psychological research also demonstrates how the coping mechanisms that children of mentally ill parents employ impact their development into adult life. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract………………………………………………….i Acknowledgements……………………………………..iii Introduction……………………………………………....1 i. Memoirs and Authors……………………………1 ii. Background of Mental Illnesses………………...6 iii. Link Between creativity and mental Illness.........8 The Hemingway Family: Strange Tribe……………………12 The Styron Family: Darkness Visible and Reading my Father ………………………………………21 The Vonnegut Family: The Eden Express and Just Like Someone Without Mental Illness Only More So…………………………………………………………26 Conclusion………………………………………………..36 Bibliography………………………………………………38 Academic Vita…………………………………………….41 iii Acknowledgements Thank you to Dr. -

Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway

MARTHA GELLHORN AND ERNEST HEMINGWAY: A LITERARY RELATIONSHIP H. L. Salmon, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2003 APPROVED: Timothy Parrish, Major Professor Peter Shillingsburg, Minor Professor Jacqueline Vanhoutte, Committee Member Brenda Sims, Chair, Graduate Studies in English C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Salmon, H. L., Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway: A Literary Relationship, Master of Arts (English). May 2003. 55 pp. Martha Gellhorn and Ernest Hemingway met in Key West in 1937, married in 1941, and divorced in 1945. Gellhorn’s work exhibits a strong influence from Hemingway’s work, including collaboration on her work during their marriage. I will discuss three of her six novels: WMP (1934), Liana (1944), and Point of No Return (1948). The areas of influence that I will rely on in many ways follow the stages Harold Bloom outlines in Anxiety of Influence. Gellhorn’s work exposes a stage of influence that Bloom does not describe—which I term collaborative. By looking at Hemingway’s influence in Gellhorn’s writing the difference between traditional literary influence and collaborative influence can be compared and analyzed, revealing the footprints left in a work by a collaborating author as opposed to simply an influential one. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Tim Parrish, who from its inception encouraged me to take on this project and whose encouragement throughout my degree work has been insightful and inspiring. Dr. Peter Shillingsburg served as a reader and mentor, and his high standards and personal integrity challenged me to make sure my own scholarship is a credible as his own. -

Ernest Hemingway's Mistresses and Wives

Ernest Hemingway’s Mistresses and Wives: Exploring Their Impact on His Female Characters by Stephen E. Henrichon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Phillip Sipiora, Ph. D. Lawrence R. Broer, Ph. D. Victor Peppard, Ph. D. Date of Approval: October 28, 2010 Keywords: Up in Michigan, Cat in the Rain, Canary for One, Francis Macomber, Kilimanjaro, White Elephants, Nobody Ever Dies, Seeing-Eyed Dog © Copyright 2010, Stephen E. Henrichon TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ i CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2: MICHIGAN: WHERE IT ALL BEGAN ....................................................9 CHAPTER 3: ADULTERY, SEPARATION AND DIVORCE ......................................16 CHAPTER 4: AFRICA ....................................................................................................29 CHAPTER 5: THE WAR YEARS AND BEYOND........................................................39 CHAPTER 6: CONCLUSION .........................................................................................47 CHAPTER 7: REFERENCES ..........................................................................................52 i ABSTRACT “Conflicted” succinctly describes Ernest Hemingway. He had a strong desire -

Ernest Hemingway's Mistresses and Wives

University of South Florida Digital Commons @ University of South Florida Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 10-28-2010 Ernest Hemingway’s Mistresses and Wives: Exploring Their Impact on His Female Characters Stephen E. Henrichon University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Henrichon, Stephen E., "Ernest Hemingway’s Mistresses and Wives: Exploring Their Impact on His Female Characters" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd/3663 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ernest Hemingway’s Mistresses and Wives: Exploring Their Impact on His Female Characters by Stephen E. Henrichon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Phillip Sipiora, Ph. D. Lawrence R. Broer, Ph. D. Victor Peppard, Ph. D. Date of Approval: October 28, 2010 Keywords: Up in Michigan, Cat in the Rain, Canary for One, Francis Macomber, Kilimanjaro, White Elephants, Nobody Ever Dies, Seeing-Eyed Dog © Copyright 2010, Stephen E. Henrichon TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT -

HEMINGWAY's SHORT WORKS and LONG-STANDING INFLUENCE on LITERATURE: MEN WITHOUT WOMEN by Katelyn Wilder Senior Honors Thesis

HEMINGWAY’S SHORT WORKS AND LONG-STANDING INFLUENCE ON LITERATURE: MEN WITHOUT WOMEN by Katelyn Wilder Senior Honors Thesis Appalachian State University Submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts May, 2020 Approved by: __________________________________________________________________ Carl Eby, Thesis Director __________________________________________________________________ William Atkinson, Reader __________________________________________________________________ Michael Wilson, Reader __________________________________________________________________ Jennifer Wilson, Departmental Honors Director Wilder 1 INTRODUCTION Ernest Hemingway is among the most influential American writers of the 20th century, if not the most considering his title of the literary “voice of the Lost Generation” (Muller 8). However, today his innovations often go overlooked by critics and students of literature. It is hard to see an artist with fresh eyes through traditions and techniques they -- not necessarily created-- but popularized. Therefore, this thesis will seek to analyze one of Hemingway’s most successful and neglected short story collections, Men Without Women. Many of Hemingway’s craft and style techniques in Men Without Women have become norms of American fiction, so much that readers unfamiliar with the traditions that came before Hemingway may no longer even recognize them as techniques. In Men Without Women, each work focuses on at least one specific crafting element: these elements overall serve as a throughline of two strands (or theses) throughout the collection, and these strands seem to parallel throughout the work, until the final piece where they collide and reveal a deeper new approach to not only writing and craft, but the idea of a collection itself. Therefore, a major theme of the collection is poioumenon. -

Ernest Hemingway, the False Macho

Essay Men and Masculinities 15(4) 424-431 ª The Author(s) 2012 Ernest Hemingway, the Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1097184X12455786 False Macho http://jmm.sagepub.com John Hemingway1 Certainly, when people think of Ernest Hemingway what comes to mind for most is the idea that he was a ‘‘man’s man,’’ a true macho who loved in equal parts drinking, hunting, war, and womanizing. He is associated with Pamplona and the running of the bulls, corrida, deep-sea fishing for marlin in the Caribbean, and the shooting of lions and water buffalo in East Africa. He was a man of action, the Lord Byron of his age, seriously wounded in Italy in the First World War, the survivor of two airplane crashes and, of course, as a writer someone who won both the Pulitzer and the Nobel Prize for literature. Yet, while all of the above is true, this traditional image of my grandfather was problematic for me as I was growing up. Being a part of the family I couldn’t, like most of my grandfather’s many admirers, look at the man and just see the legendary writer and world traveler. This was because my father, Ernest’s youngest son Gregory, seemed to be as different as you could be from the author of The Old Man and the Sea. From his early teenage years, Gregory cross-dressed and eventually underwent a series of operations at the age of sixty-four to change his sex. Needless to say, there were many times when I’d ask myself, just what connection could there possibly be between this cross-dressing, transsexual Doctor of Medicine (MD), and America’s macho icon? While there didn’t seem to be any on the surface, even as a boy I knew that there was a strong link between the two men. -

Box and Folder Listing

CLARKE HISTORICAL LIBRARY CENTRAL MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY Ernest Hemingway Collection, 1901, 2014, and undated 6 cubic ft. (in 7 boxes, 7 Oversized folders, 4 reels in 4 boxes, and 53 framed items) ACQUISITION: The collection was donated in several parts by Michael Federspiel and the Michigan Hemingway Society, Acc# 67522 (Oct. 4, 2002), 67833 (April 2003), 68091 (Oct. 2003), 68230 (Dec. 2003), by Ken Mark and the Michigan Hemingway Society, 68076 (Oct. 2003), Rebecca Zeiss, 68386 (Oct. 2003), 68415 by Ken Mark (April 27, 2004), by Charlotte Ponder 68419 (May 2004), 68698 by Federspiel (Sept. 30, 2004), 68848 by the Hemingway Society (Dec.6, 2004), 69475, 70252, 70401 (April 2007), 70680-70682 and 70737 (Summer 2007), 71358 (July 2008), 71396 (Aug. 2008), 71455 (Oct. 2008), 72160 (Nov. 2010), 73641 (Sept. 2012), 73683 by Pat Davis (Sept. 2012), 73751 (Nov. 2012), 72579 (Nov. 2013), 74631 (Aug. 2014), no MS#. The collection is ongoing. ACCESS: The collection is open to researchers. COPYRIGHT: Copyright is held neither by CMU nor the Clarke. Copyright of letters composed by EH is held by the The Ernest Hemingway Foundation and Society. PHOTOGRAPHS: In Boxes 2-6. PROCESSED BY: M. Matyn, 2003, 2009, ongoing. Biography: Ernest Hemingway was born July 21, 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, the son of Clarence E. Hemingway, a doctor, and Grace Hall-Hemingway, a musician and voice teacher. He had four sisters and a brother. Every summer, the family summered at the family cottage, named Windemere, on Walloon Lake near Petoskey, Michigan. After Ernest graduated from high school in June 1917, he joined the Missouri Home Guard. -

New Details on Cuba Trip Park, and Also a Part of Our Tour

January 2017 Website: hemingway.astate.edu Phone: 870-598-3487 Hemingway-Perkins Duck Hunt Re-Created From January 13-17, we were joined by two special guests, John Hemingway (Ernest’s grandson) and Jenny Phillips (the granddaughter of Ernest’s editor Maxwell Perkins). In December 1932, Max met Ernest in Arkansas for a week of duck hunting in south Arkansas. It was a rare occasion, a meeting between one of America’s great writers and one of its finest editors. This winter, we re-created this duck hunting experience, visiting the sites that made the original trip special. We began the weekend in Piggott with a tour of the museum and a quail hunt, at Liberty Hill Outfitters. Quail hunting was one of Ernest’s favorite pastimes in Arkansas. Following our time in Piggott, we headed south to the White River, near Pendleton. We spent the next two days duck hunting the same areas as Perkins and Hemingway, who took the Delta Star train from Helena, disembarking at the Benzal Bridge. They boarded a house boat at the bridge’s base and spent the next week taking the boat to locations up and down the river to Cayo Guillermo, Cuba—one of the settings hunt. When they needed supplies, for Islands in the Stream they visited the Yancopin Store, now a part of the Delta Heritage Trail State New Details on Cuba Trip Park, and also a part of our tour. We’ve settled on our final details for We ended our weekend in Helena our 2017 Friends trip to Cuba. -

Box and Folder Listing

CLARKE HISTORICAL LIBRARY CENTRAL MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY Ernest Hemingway Collection, 1901, 2014, and undated 6.5 cubic ft. (in 8 boxes, 9 Oversized folders, 4 reels in 4 film canisters* and 52 framed items) ACQUISITION: The collection was donated in several parts by Michael Federspiel and the Michigan Hemingway Society, Acc# 67522 (Oct. 4, 2002), 67833 (April 2003), 68091 (Oct. 2003), 68230 (Dec. 2003), by Ken Mark and the Michigan Hemingway Society, 68076 (Oct. 2003), Rebecca Zeiss, 68386 (Oct. 2003), 68415 by Ken Mark (April 27, 2004), by Charlotte Ponder 68419 (May 2004), 68698 by Federspiel (Sept. 30, 2004), 68848 by the Hemingway Society (Dec.6, 2004), 69475, 70252, 70401 (April 2007), 70680-70682 and 70737 (Summer 2007), 71358 (July 2008), 71396 (Aug. 2008), 71455 (Oct. 2008), 72160 (Nov. 2010), 73641 (Sept. 2012), 73683 by Pat Davis (Sept. 2012), 73751 (Nov. 2012), 72579 (Nov. 2013), 74631 (Aug. 2014), 74561 (Nov. 2014), 74763 and 74772 (Dec. 2014), M. Federspiel 2019 Addition 76686 (2019), 76811 (2020), no MS#. The collection is ongoing. ACCESS: The collection is open to researchers. COPYRIGHT: Copyright is held neither by CMU nor the Clarke. Copyright of letters composed by EH is held by The Ernest Hemingway Foundation and Society. PHOTOGRAPHS: In Boxes 2-6, 9. NOTE: * for purposes of encoding the film canisters are listed as Box #8, in addition to other boxes in the collection. PROCESSED BY: M. Matyn, 2003, 2009, ongoing. Biography: Ernest Hemingway was born July 21, 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, the son of Clarence E. Hemingway, a doctor, and Grace Hall-Hemingway, a musician and voice teacher. -

Three Paths to Religious Integration in Ernest Hemingway's

THREE PATHS TO RELIGIOUS INTEGRATION IN ERNEST HEMINGWAY’S WAR FICTION A DISSERTATION IN English and Humanities Consortium Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by TIMOTHY JAMES PINGELTON B.A., University of Missouri-Kansas City, 1994 M.F.A., San Diego State University, 1997 Kansas City, Missouri 2018 © 2018 TIMOTHY JAMES PINGELTON ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THREE PATHS TO RELIGIOUS INTEGRATION IN ERNEST HEMINGWAY’S WAR FICTION Timothy James Pingelton, Doctor of Philosophy Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2018 ABSTRACT My dissertation studies religiosity in Ernest Hemingway’s war fiction in terms of how his soldier characters connect to the divine. The means to understanding this connection is in refining how the characters express the utility of this connection and how these features fit into larger structural ideals. I argue that the wartime characters integrate with the divine through various methods: by contact with nature, by enacting a ritual, or by embodying Christian manliness. I base my dissertation on relevant phenomenological theories but also considers broader structural-functional theories, and I form the approach on structuralism in that I look at both single works and at the war fiction as a whole as well as looking for connections between literature and culture. Furthermore, I look to the theories of Northrop Frye in analyzing this literature because Frye’s structuralism allows for genre-bending oeuvres such as Hemingway’s. I argue that, contrary to much literary criticism, the Hemingway wartime protagonists are theists who seek the divine in times ii of conflict, but, unlike the notion of “no atheists in the foxholes,” these characters harbor their religiosity not situationally but throughout their lives.