(1867-1916), Focusing on Me/An a Disse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beneficence of Gayface Tim Macausland Western Washington University, [email protected]

Occam's Razor Volume 6 (2016) Article 2 2016 The Beneficence of Gayface Tim MacAusland Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation MacAusland, Tim (2016) "The Beneficence of Gayface," Occam's Razor: Vol. 6 , Article 2. Available at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu/vol6/iss1/2 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Student Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occam's Razor by an authorized editor of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MacAusland: The Beneficence of Gayface THE BENEFICENCE OF GAYFACE BY TIM MACAUSLAND In 2009, veteran funny man Jim Carrey, best known to the mainstream within the previous decade with for his zany and nearly cartoonish live-action lms like American Beauty and Rent. It was, rather, performances—perhaps none more literally than in that the actors themselves were not gay. However, the 1994 lm e Mask (Russell, 1994)—stretched they never let it show or undermine the believability his comedic boundaries with his portrayal of real- of the roles they played. As expected, the stars life con artist Steven Jay Russell in the lm I Love received much of the acclaim, but the lm does You Phillip Morris (Requa, Ficarra, 2009). Despite represent a peculiar quandary in the ethical value of earning critical success and some of Carrey’s highest straight actors in gay roles. -

Leaders and Heroes: Modern Day Archetypes Sophon Shadraconis Claremont Graduate University, [email protected]

LUX: A Journal of Transdisciplinary Writing and Research from Claremont Graduate University Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 15 2013 Leaders and Heroes: Modern Day Archetypes Sophon Shadraconis Claremont Graduate University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/lux Part of the Business Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Shadraconis, Sophon (2013) "Leaders and Heroes: Modern Day Archetypes," LUX: A Journal of Transdisciplinary Writing and Research from Claremont Graduate University: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 15. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/lux/vol3/iss1/15 Shadraconis: Leaders and Heroes: Modern Day Archetypes Shadraconis 1 Leaders and Heroes: Modern Day Archetypes Sophon Shadraconis Claremont Graduate University Abstract This paper explores the salience of archetypes through modern day idealization of leaders as heroes. The body of research in evolutionary psychology and ethology provide support for archetypal theory and the influence of archetypes (Hart & Brady, 2005; Maloney, 1999). Our idealized self is reflected in archetypes and it is possible that we draw on archetypal themes to compensate for a reduction in meaning in our modern day work life. Archetypal priming can touch a person’s true self and result in increased meaning in life. According to Faber and Mayer (2009), drawing from Jung (1968), an archetype is an, “internal mental model of a typical, generic story character to which an observer might resonate emotionally” (p. 307). Most contemporary researchers maintain that archetypal models are transmitted through culture rather than biology, as Jung originally argued (Faber & Mayer, 2009). Archetypes as mental models can be likened to image schemas, foundational mind/brain structures that are developed during human pre-verbal experience (Merchant, 2009). -

Goethe, the Japanese National Identity Through Cultural Exchange, 1889 to 1989

Jahrbuch für Internationale Germanistik pen Jahrgang LI – Heft 1 | Peter Lang, Bern | S. 57–100 Goethe, the Japanese National Identity through Cultural Exchange, 1889 to 1989 By Stefan Keppler-Tasaki and Seiko Tasaki, Tokyo Dedicated to A . Charles Muller on the occasion of his retirement from the University of Tokyo This is a study of the alleged “singular reception career”1 that Goethe experi- enced in Japan from 1889 to 1989, i. e., from the first translation of theMi gnon song to the last issues of the Neo Faust manga series . In its path, we will high- light six areas of discourse which concern the most prominent historical figures resp. figurations involved here: (1) the distinct academic schools of thought aligned with the topic “Goethe in Japan” since Kimura Kinji 木村謹治, (2) the tentative Japanification of Goethe by Thomas Mann and Gottfried Benn, (3) the recognition of the (un-)German classical writer in the circle of the Japanese national author Mori Ōgai 森鴎外, as well as Goethe’s rich resonances in (4) Japanese suicide ideals since the early days of Wertherism (Ueruteru-zumu ウェル テルヅム), (5) the Zen Buddhist theories of Nishida Kitarō 西田幾多郎 and D . T . Suzuki 鈴木大拙, and lastly (6) works of popular culture by Kurosawa Akira 黒澤明 and Tezuka Osamu 手塚治虫 . Critical appraisal of these source materials supports the thesis that the polite violence and interesting deceits of the discursive history of “Goethe, the Japanese” can mostly be traced back, other than to a form of speech in German-Japanese cultural diplomacy, to internal questions of Japanese national identity . -

Race Dirt 1400M TWO−YEAR−OLDS Course Record:24Dec.16 1:23.0 DES,WEIGHT for AGE,MAIDEN

HANSHIN SUNDAY,DECEMBER 20TH Post Time 10:05 1 ! Race Dirt 1400m TWO−YEAR−OLDS Course Record:24Dec.16 1:23.0 DES,WEIGHT FOR AGE,MAIDEN Value of race: 9,680,000 Yen 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th Added Money(Yen) 5,100,000 2,000,000 1,300,000 770,000 510,000 Stakes Money(Yen) 0 0 0 Ow. Dearest Club Co.,Ltd. 2,770,000 S 20101 Life30102M 10001 1 1 55.0 Hideaki Miyuki(7.0%,61−80−72−654,13th) Turf10001 I 00000 Allure Bulto(JPN) Dirt20101L 00000 +Fenomeno(0.34) +Matsurida Gogh C2,b. Katsuichi Nishiura(5.2%,14−19−16−220,111st) Course10100E 00000 Wht. ,Triandrus ,Developpe 30Mar.18 Dearest Club Wet 00000 6Dec.20 HANSHIN MDN D1200St 14 12 1:13.2 2nd/16 Suguru Hamanaka 55.0 446" True Barows 1:13.2 <NS> Allure Bulto <5> Daisy Moon 25Oct.20 KYOTO MDN D1200Go 8 6 1:12.5 4th/12 Hideaki Miyuki 55.0 450' Sugino Majesty 1:12.1 <NK> Satono Apollon <1/2> Land Volcano 11Oct.20 KYOTO NWC T1800Go 2 3 1:51.5 11th/14 Hideaki Miyuki 55.0 460% Vasa 1:49.7 <HD> Brave Jackal <3/4> Badenweiler Ow. Yoshio Matsumoto 0 S 10001 Life20002M 10001 1 2 52.0 Keishi Yamada(3.2%,17−15−23−476,57th) Turf00000 I 00000 Meisho Honami(JPN) Dirt20002L 00000 +I’ll Have Another(0.86)+Galileo F2,ch. Yoshiyuki Arakawa(5.6%,17−35−25−229,87th) Course10001E 00000 Wht. ,Do The Bosanova ,Sateen 23Feb.18 Mitsuishi Kawakami Bokujo Wet 00000 5Dec.20 CHUKYO MDN D1800St 4433 2:00.013th/16Shinji Kawashima 54.0 422* Violet Zinc 1:55.9 <1 1/2> Love of My Life <3/4> Square Sail 21Nov.20 HANSHIN NWC D1200St 8 8 1:16.3 9th/15 Ken Tanaka 54.0 424( Le Chat Libre 1:14.0 <1/2+1/2> Ciel Bleu <> Baby Ash Ow. -

Supisr..S Ft -- T T??Ff& Hc'ri.' Cf the Motmn Ti Queen

From San Francre: . ; Lurlioe, Jun 30. For 8fr Francisco; v Jbiatsooio, Jul From Vancouver: ' Jlakura, Jolf 15," For Vancouverr . ; H pi Niagara, JoJil4;r ' "a Evening . ; y; w . uunciui, t f '' bait ioo, iiu. r ' PAGEs.--noKOLU- Lu, ; : V' Star.-Vo- l XXL No. 693 4 ' .' ;' f "? - i v '? 16 op Hawaii, Tuesday, so, pages X'i tebeitorIt jone, i9i4.:i6 PBICE FIVE CENT3 rnn MDEPI8.T0 BE MYSTERY SURROUNDS DEATH OF GOVEIiilRl uuil mm .uiiC-ik-- ii J V DR. EDWARD HiARMITAGE. WELL-- II Hit mm OVER TO VELL PLEASED? I KNOWN PHYSICIAN AND LINGUIST V I V m- trip .- j HILO Juno 30.A myatery aurrounda tha'deatf cf Or. dward H ArmU, viitiiiis 4 iliiioii tagef welt fcnown over the iatanda for hia ability a a phyalclan. and linau- - William A. Wall, City Jt)c accompllahmenta, whoao body waa found under threo feet of water on Attorney .fcr the U. S. District Engineer, Cocoanut laland laat ovemng. A coroners Jury invettrgation will b under- Comrnissionwof J. A. M; Osorio, AnnouncesliiiiiiiiipiHis Position to 500 SuffragHtesAiohg Similar Ex-utfic- Attorney Would Have Judge : iWill Be io Manager taken aometime today, and tha reault of it may clear, up the myatery and Kealoha's Successor, Is-- Lines to Those Followed bv Champ If Or. waa Is' Clark Sees Nation1 i-- . determine Armitage a victim of foul play, or took'his own life, ? Sewer - - , v near t of and Waterworks i . sup.n i yiuiui y iipniP uoie tvmence or met death from' accidental cause. The opinion, here la divided ao far, inis r.inrmnn?. -

Curtis Kheel Scripts, 1990-2007 (Bulk 2000-2005)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4b69r9wq No online items Curtis Kheel scripts, 1990-2007 (bulk 2000-2005) Finding aid prepared by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Curtis Kheel scripts, 1990-2007 PASC 343 1 (bulk 2000-2005) Title: Curtis Kheel scripts Collection number: PASC 343 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 8.5 linear ft.(17 boxes) Date (bulk): Bulk, 2000-2005 Date (inclusive): 1990-2007 (bulk 2000-2005) Abstract: Curtis Kheel is a television writer and supervising producer. The collection consists of scripts for the television series, most prominently the series, Charmed. Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Creator: Kheel, Curtis Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

Japanese Literature Quiz Who Was the First Japanese Novelist to Win the Nobel Prize for Literature?

Japanese Literature Quiz Who was the first Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasunari Kawabata ② Soseki Natsume ③ Ryunosuke Akutagawa ④ Yukio Mishima Who was the first Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasunari Kawabata ② Soseki Natsume ③ Ryunosuke Akutagawa ④ Yukio Mishima Who was the second Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasushi Inoue ② Kobo Abe ③ Junichiro Tanizaki ④ Kenzaburo Oe Who was the second Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasushi Inoue ② Kobo Abe ③ Junichiro Tanizaki ④ Kenzaburo Oe What is the title of Soseki Natsume's novel, "Wagahai wa ( ) de aru [I Am a ___]"? ① Inu [Dog] ② Neko [Cat] ③ Saru [Monkey] ④ Tora [Tiger] What is the title of Soseki Natsume's novel, "Wagahai wa ( ) de aru [I Am a ___]"? ① Inu [Dog] ② Neko [Cat] ③ Saru [Monkey] ④ Tora [Tiger] Which hot spring in Ehime Prefecture is written about in "Botchan," a novel by Soseki Natsume? ① Dogo Onsen ② Kusatsu Onsen ③ Hakone Onsen ④ Arima Onsen Which hot spring in Ehime Prefecture is written about in "Botchan," a novel by Soseki Natsume? ① Dogo Onsen ② Kusatsu Onsen ③ Hakone Onsen ④ Arima Onsen Which newspaper company did Soseki Natsume work and write novels for? ① Mainichi Shimbun ② Yomiuri Shimbun ③ Sankei Shimbun ④ Asahi Shimbun Which newspaper company did Soseki Natsume work and write novels for? ① Mainichi Shimbun ② Yomiuri Shimbun ③ Sankei Shimbun ④ Asahi Shimbun When was Murasaki Shikibu's "Genji Monogatari [The Tale of Genji] " written? ① around 1000 C.E. ② around 1300 C.E. ③ around 1600 C.E. ④ around 1900 C.E. When was Murasaki Shikibu's "Genji Monogatari [The Tale of Genji] " written? ① around 1000 C.E. -

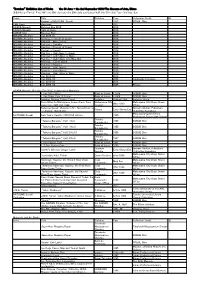

Soseki's Botchan Dango ' Label Tamanoyu Kaminoyu Yojyoyu , The

"Botchan" Exhibition List of Works the 30 June - the 2nd September 2018/The Museum of Arts, Ehime ※Exhibition Period First Half: the 30th Jun sat.-the 29th July sun/Latter Half: the 31th July Tue.- 2nd Sep. Sun Artist Title Piblisher Year Collection Credit ※ Portrait of NATSUME Soseki 1912 SOBUE Shin UME Kayo Botchans' 2017 ASADA Masashi Botchan Eye 2018' 2018 ASADA Masashi Cats at Dogo 2018 SOBUE Shin Botchan Bon' 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2018-01 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - White Heron 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Camellia 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi-Neko in Green 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko at Night 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko with Blue Sky 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Turner Island 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Pegasus 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Sabi -Neko 1 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Sabi -Neko 2 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko in White 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2013-03 2013 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2002-02 2002 Takahashi Collection MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2014-02 2014 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2006-04 2006 Private ASADA Masashi 'Botchan Eye 2018' Collaboration Materials 1 Yen Bill (2 Bills) Bank of Japan c.1916 SOBUE Shin 1 Yen Silver Coin (3 Coins) Bank of Japan c.1906 SOBUE Shin Iyotetsu Railway Ticket (Copy) Iyotetsu Original:1899 Iyotetsu Group From Mitsu to Matsuyama, Lower Class, Fare Matsuyama City Matsuyama City Dogo Onsen after 1950 3sen 5rin , 28th Oct.,1888 Tourism Office Natsume Soseki, Botchan 's Inn Yamashiroya is Iwanami Shoten, Publishers. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Japanese Studies at Manchester Pre-Arrival Reading Suggestions For

Japanese Studies at Manchester Pre-arrival Reading Suggestions for the 2020-2021 Academic Year This is a relatively short list of novels, films, manga, and language learning texts which will be useful for students to peruse and invest in before arrival. Students must not consider that they ought to read all the books on the list, or even most of them, but those looking for a few recommendations of novels, histories, or language texts, should find good suggestions for newcomers to the field. Many books can be purchased second-hand online for only a small price, and some of the suggestions listed under language learning will be useful to have on your shelf throughout year one studies and beyond. Japanese Society Ronald Dore City Life in Japan describes Tokyo society in the early 1950s Takie Lebra's book, Japanese Patterns of Behavior (NB US spelling) Elisabeth Bumiller, The Secrets of Mariko Some interesting podcasts about Japan: Japan on the record: a podcast where scholars of Japan react to issues in the news. https://jotr.transistor.fm/episodes Meiji at 150: the researcher Tristan Grunow interviews specialists in Japanese history, literature, art, and culture. https://meijiat150.podbean.com/ Japanese History Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan Marius B. Jansen, The Making of Modern Japan John W. Dower Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II Christopher Goto-Jones, Modern Japan: A Very Short Introduction (can be read in a day). Religion in Japan Ian Reader, Religion in Contemporary Japan Japanese Literature The Penguin -

Worcester Salt

well that arm or STORY OF TWO WOMEN. might have had a joyous journey, full of "We are going," she said. "Take mt for Inhabiting the old mansion of his hap "By the way, who Is this Christopher 'Pretty plowed up. to him!" 1 said he. the true savor of brave travel. But he pier days. God knows how gladly Columbns ?" asked an earnest seeker af-- his'n,' Was How - What the Trouble and it Resulted. ;, Did she him? have seen did not mend. He wasted daily. His love would have reinstated him there. But ter was first assist- BRENT "I amputation performed I braved Dr. I truth. "He the very JOHN - trances. We could Pathie's and she could not love so came SAY. became displeasure me, for less." - WHAT EACH HAS TO ABOUT THI8 HOST sleep deathly away, ed to come to America," re : haste. Brave led her to the bedside of her lover. we looked and immigrant ."Then I'm dum glad there's no saw- INTERESTING MA TTEH SOMETHING NEV- not wear him out with and up Luggernel springs ER BEFORE IN OUR ' EXPERI- bore like a brave. Brent was still in a stunor. We were the to a plied the man who had big stocks of truth -- bones about I don't believe nater means EQUALLED. heart! be up alley together, John, give you - By THE0D0EE WEJTHE0P. , ENCE. - last one noon we drew' out of alone. V ; "': chance to snatch from onhand. a man's leg or arm to go' until she breaks '' And at my destiny away - The of each is both are Black and saw before os, She Btood looking at him a moment me." ' the solid bone, so that it aint to be sot story brief, but the Hills, - Deserving Praise. -

Kokoro and the Agony of the Individual

Kokoro and the Agony of the Individual NICULINA NAE In this article I examine changes in the concept of identity as a result of the upheaval in relationships brought about by the Meiji Restoration. These changes are seen as reflected in Sôseki’s novel Kokoro. I discuss two of the most important concepts of modern Japanese, those of individual (個人 kojin)andsociety (社会 shakai), both of which were introduced under the influence of the Meiji intelligentsia’s attempts to create a new Japan following the European model. These concepts, along with many others, reflect the tendency of Meiji intellectuals to discard the traditional Japanese value systems, where the group, and not the individual, was the minimal unit of society. The preoccupation with the individual and his own inner world is reflected in Natsume Sôseki’s Kokoro. The novel is pervaded by a feeling of confusion between loyalty to the old values of a dying era and lack of attachment towards a new and materialistic world. The novel Kokoro appeared for the first time in the Asahi Shimbun between 20 April and 11 August 1914. It reflects the maturation of Sôseki’s artistic technique, being his last complete work of pure fiction (Viglielmo, 1976: 167). As McClellan (1969) pointed out, Kokoro is an allegory of its era, an idea sustained also by the lack of names for characters, who are simply “Sensei”,“I”,“K”,etc.Itdepictsthetormentofaman,Sensei,whohasgrownupina prosperous and artistic family, and who, after his parents’ death, finds out that the real world is different from his own naive, idealistic image.