Spiritual Discernment in Soseki Natsume's Kokoro Daniel Wright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Literature Quiz Who Was the First Japanese Novelist to Win the Nobel Prize for Literature?

Japanese Literature Quiz Who was the first Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasunari Kawabata ② Soseki Natsume ③ Ryunosuke Akutagawa ④ Yukio Mishima Who was the first Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasunari Kawabata ② Soseki Natsume ③ Ryunosuke Akutagawa ④ Yukio Mishima Who was the second Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasushi Inoue ② Kobo Abe ③ Junichiro Tanizaki ④ Kenzaburo Oe Who was the second Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasushi Inoue ② Kobo Abe ③ Junichiro Tanizaki ④ Kenzaburo Oe What is the title of Soseki Natsume's novel, "Wagahai wa ( ) de aru [I Am a ___]"? ① Inu [Dog] ② Neko [Cat] ③ Saru [Monkey] ④ Tora [Tiger] What is the title of Soseki Natsume's novel, "Wagahai wa ( ) de aru [I Am a ___]"? ① Inu [Dog] ② Neko [Cat] ③ Saru [Monkey] ④ Tora [Tiger] Which hot spring in Ehime Prefecture is written about in "Botchan," a novel by Soseki Natsume? ① Dogo Onsen ② Kusatsu Onsen ③ Hakone Onsen ④ Arima Onsen Which hot spring in Ehime Prefecture is written about in "Botchan," a novel by Soseki Natsume? ① Dogo Onsen ② Kusatsu Onsen ③ Hakone Onsen ④ Arima Onsen Which newspaper company did Soseki Natsume work and write novels for? ① Mainichi Shimbun ② Yomiuri Shimbun ③ Sankei Shimbun ④ Asahi Shimbun Which newspaper company did Soseki Natsume work and write novels for? ① Mainichi Shimbun ② Yomiuri Shimbun ③ Sankei Shimbun ④ Asahi Shimbun When was Murasaki Shikibu's "Genji Monogatari [The Tale of Genji] " written? ① around 1000 C.E. ② around 1300 C.E. ③ around 1600 C.E. ④ around 1900 C.E. When was Murasaki Shikibu's "Genji Monogatari [The Tale of Genji] " written? ① around 1000 C.E. -

Soseki's Botchan Dango ' Label Tamanoyu Kaminoyu Yojyoyu , The

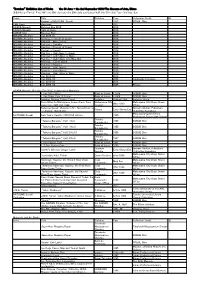

"Botchan" Exhibition List of Works the 30 June - the 2nd September 2018/The Museum of Arts, Ehime ※Exhibition Period First Half: the 30th Jun sat.-the 29th July sun/Latter Half: the 31th July Tue.- 2nd Sep. Sun Artist Title Piblisher Year Collection Credit ※ Portrait of NATSUME Soseki 1912 SOBUE Shin UME Kayo Botchans' 2017 ASADA Masashi Botchan Eye 2018' 2018 ASADA Masashi Cats at Dogo 2018 SOBUE Shin Botchan Bon' 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2018-01 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - White Heron 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Camellia 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi-Neko in Green 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko at Night 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko with Blue Sky 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Turner Island 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Pegasus 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Sabi -Neko 1 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Sabi -Neko 2 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko in White 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2013-03 2013 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2002-02 2002 Takahashi Collection MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2014-02 2014 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2006-04 2006 Private ASADA Masashi 'Botchan Eye 2018' Collaboration Materials 1 Yen Bill (2 Bills) Bank of Japan c.1916 SOBUE Shin 1 Yen Silver Coin (3 Coins) Bank of Japan c.1906 SOBUE Shin Iyotetsu Railway Ticket (Copy) Iyotetsu Original:1899 Iyotetsu Group From Mitsu to Matsuyama, Lower Class, Fare Matsuyama City Matsuyama City Dogo Onsen after 1950 3sen 5rin , 28th Oct.,1888 Tourism Office Natsume Soseki, Botchan 's Inn Yamashiroya is Iwanami Shoten, Publishers. -

Japanese Studies at Manchester Pre-Arrival Reading Suggestions For

Japanese Studies at Manchester Pre-arrival Reading Suggestions for the 2020-2021 Academic Year This is a relatively short list of novels, films, manga, and language learning texts which will be useful for students to peruse and invest in before arrival. Students must not consider that they ought to read all the books on the list, or even most of them, but those looking for a few recommendations of novels, histories, or language texts, should find good suggestions for newcomers to the field. Many books can be purchased second-hand online for only a small price, and some of the suggestions listed under language learning will be useful to have on your shelf throughout year one studies and beyond. Japanese Society Ronald Dore City Life in Japan describes Tokyo society in the early 1950s Takie Lebra's book, Japanese Patterns of Behavior (NB US spelling) Elisabeth Bumiller, The Secrets of Mariko Some interesting podcasts about Japan: Japan on the record: a podcast where scholars of Japan react to issues in the news. https://jotr.transistor.fm/episodes Meiji at 150: the researcher Tristan Grunow interviews specialists in Japanese history, literature, art, and culture. https://meijiat150.podbean.com/ Japanese History Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan Marius B. Jansen, The Making of Modern Japan John W. Dower Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II Christopher Goto-Jones, Modern Japan: A Very Short Introduction (can be read in a day). Religion in Japan Ian Reader, Religion in Contemporary Japan Japanese Literature The Penguin -

Kokoro and the Agony of the Individual

Kokoro and the Agony of the Individual NICULINA NAE In this article I examine changes in the concept of identity as a result of the upheaval in relationships brought about by the Meiji Restoration. These changes are seen as reflected in Sôseki’s novel Kokoro. I discuss two of the most important concepts of modern Japanese, those of individual (個人 kojin)andsociety (社会 shakai), both of which were introduced under the influence of the Meiji intelligentsia’s attempts to create a new Japan following the European model. These concepts, along with many others, reflect the tendency of Meiji intellectuals to discard the traditional Japanese value systems, where the group, and not the individual, was the minimal unit of society. The preoccupation with the individual and his own inner world is reflected in Natsume Sôseki’s Kokoro. The novel is pervaded by a feeling of confusion between loyalty to the old values of a dying era and lack of attachment towards a new and materialistic world. The novel Kokoro appeared for the first time in the Asahi Shimbun between 20 April and 11 August 1914. It reflects the maturation of Sôseki’s artistic technique, being his last complete work of pure fiction (Viglielmo, 1976: 167). As McClellan (1969) pointed out, Kokoro is an allegory of its era, an idea sustained also by the lack of names for characters, who are simply “Sensei”,“I”,“K”,etc.Itdepictsthetormentofaman,Sensei,whohasgrownupina prosperous and artistic family, and who, after his parents’ death, finds out that the real world is different from his own naive, idealistic image. -

An Analysis of Characteristics of Realism Portrayed in Natsume Soseki's Novel Kokoro a Thesis by Novegi Arya Samudera Reg

AN ANALYSIS OF CHARACTERISTICS OF REALISM PORTRAYED IN NATSUME SOSEKI’S NOVEL KOKORO A THESIS BY NOVEGI ARYA SAMUDERA REG. NO. 130705073 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2020 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA i UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA ii UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA iii UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I, NOVEGI ARYA SAMUDERA, DECLARE THAT I AM THE SOLE AUTHOR OF THIS THESIS EXCEPT WHERE REFERENCE IS MADE IN THE TEXT OF THIS THESIS. THIS THESIS CONTAINS NO MATERIAL PUBLISHED ELSEWHERE OR EXTRACTED IN WHOLE OR IN PART FROM A THESIS BY WHICH I HAVE QUALIFIED FOR OR AWARDED ANOTHER DEGREE. NO OTHER PERSON’S WORK HAS BEEN USED WITHOUT DUE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IN THE MAIN TEXT OF THIS THESIS. THIS THESIS HAS NOT BEEN SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF ANOTHER DEGREE IN ANY TERTIARY EDUCATION. Signed : Date : January 4th 2020 i UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA COPYRIGHT DECLARATION NAME : NOVEGI ARYA SAMUDERA TITLE OF THESIS : AN ANALYSIS OF CHARACTERISTICS OF REALISM PORTRAYED IN NATSUME SOSEKI’S NOVEL KOKORO QUALIFICATION : S-1/SARJANA SASTRA DEPARTMENT : ENGLISH I AM WILLING THAT MY THESIS SHOULD BE AVAILABLE FOR REPRODUCTION AT THE DISCRETION OF THE LIBRARIAN OF DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH, FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA ON THE UNDERSTANDING THAT USERS ARE MADE AWARE OF THEIR OBLIGATION UNDER THE LAW OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA. Signed : Date : January 4th 2020 ii UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Allah SWT, the Almighty God and Most Beneficial for His Blessing, Grace, Guidance, and Mercy that have made this thesis come to it’s completion. -

Natsume S–Oseki Botchan

YOUNG ADULT READERS LIGHT NATSUME SOSEKI– Eli Readers is a beautifully-illustrated series of timeless classics and specially-written stories for learners of English. BOTCHAN NATSUME NATSUME Natsume Soseki– S OSEKI OSEKI Botchan - BOTCHAN Botchan is from Tokyo in Japan. He becomes a teacher and moves from the big city to a small town on an island. He thinks teaching high school students is easy, but life in the country town is different. Teaching is difficult. His students are difficult. They play tricks on him. Botchan has many problems at school and many questions. He does not know who to believe. He does not know who his friends are. Follow Botchan as he learns good from bad and right from wrong. In this reader you will find: - Information about Natsume Soseki– - Focus on sections - Glossary of difficult words - Comprehension and extension activities Tags Classic literature Y O A1 Up to 600 headwords Word count: 9450 U N G Classic Full text on CD A www.elireaders.com DUL T ELI RE A DERS | L I GH YOUNG ADULT ELI READERS LIGHT T ISBN 978-88-536-1588-6ELI s.r.l. Botchan E L www.elireaders.com T ELT YOUNG ADULT READERS LIGHT A 1 A1 YOUNG ADULT READERS LIGHT B2A1 The ELI Readers collection is a complete range of books and plays for readers of all ages, ranging from captivating contemporary stories to timeless classics. There are three series, each catering for a different age group; Young ELI Readers, Teen ELI Readers and Young Adult ELI Readers. The books are carefully edited and beautifully illustrated to capture the essence of the stories and plots. -

The Unique Cultural & Innnovative Twelfty 1820

Chekhov reading The Seagull to the Moscow Art Theatre Group, Stanislavski, Olga Knipper THE UNIQUE CULTURAL & INNNOVATIVE TWELFTY 1820-1939, by JACQUES CORY 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. of Page INSPIRATION 5 INTRODUCTION 6 THE METHODOLOGY OF THE BOOK 8 CULTURE IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES IN THE “CENTURY”/TWELFTY 1820-1939 14 LITERATURE 16 NOBEL PRIZES IN LITERATURE 16 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN 1820-1939, WITH COMMENTS AND LISTS OF BOOKS 37 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN TWELFTY 1820-1939 39 THE 3 MOST SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – FRENCH, ENGLISH, GERMAN 39 THE 3 MORE SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – SPANISH, RUSSIAN, ITALIAN 46 THE 10 SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – PORTUGUESE, BRAZILIAN, DUTCH, CZECH, GREEK, POLISH, SWEDISH, NORWEGIAN, DANISH, FINNISH 50 12 OTHER EUROPEAN LITERATURES – ROMANIAN, TURKISH, HUNGARIAN, SERBIAN, CROATIAN, UKRAINIAN (20 EACH), AND IRISH GAELIC, BULGARIAN, ALBANIAN, ARMENIAN, GEORGIAN, LITHUANIAN (10 EACH) 56 TOTAL OF NOS. OF AUTHORS IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES BY CLUSTERS 59 JEWISH LANGUAGES LITERATURES 60 LITERATURES IN NON-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES 74 CORY'S LIST OF THE BEST BOOKS IN LITERATURE IN 1860-1899 78 3 SURVEY ON THE MOST/MORE/SIGNIFICANT LITERATURE/ART/MUSIC IN THE ROMANTICISM/REALISM/MODERNISM ERAS 113 ROMANTICISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 113 Analysis of the Results of the Romantic Era 125 REALISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 128 Analysis of the Results of the Realism/Naturalism Era 150 MODERNISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 153 Analysis of the Results of the Modernism Era 168 Analysis of the Results of the Total Period of 1820-1939 -

No. 58 October 1, 2019

Publishing Date: A PR bulletin produced especially for the foreign residents of Shinjuku City 2019 October 1 No. 58 Published by: Multicultural Society Promotion Division, Regional Promotion Department, SShinjukuhinjuku CCityity Shinjuku City information can 1-4-1 Kabuki-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-8484 Tel: 03-5273-3504 Fax: 03-5273-3590 now be transmitted in Japanese, English, Chinese and Korean! Website http://www.foreign.city.shinjuku.lg.jp/en/ What is Shabereon? JJapanese-apanese- ““ShabereonShabereon ’’19”19” Shabereon is a speech contest LLanguageanguage in which foreign residents who live, work or go to school in SSpeechpeech Shinjuku City express their IInterviewnterview wwithith tthehe WWinnerinner everyday thoughts and dreams CContestontest in Japanese. The most recent Shabereon took place this past June 15, marking the contest’s twenty-eighth year. SShabereonhab ereon wwinnerinner Amarjargal Jargalmaa This year’s winner was Amarjargal Jargalmaa from Mongolia. In a presentation entitled “I Won’t Run Away,” she shared her earnest thoughts in fl uent Japanese on the work she plans to do related to environmental pollution and biotechnology. We asked Amarjargal how she studied Japanese. How do you study the Japanese language? What do you think is the key to enjoying learning Q Japanese? Do you have any advice for people who Q are studying the language? A I always study the textbook in advance. I’ve also listened to NHK radio news for about a year. I think it’s important to talk with the Japanese people A around you. I heard that this was difficult, though, since Japanese people are shy and usually won’t start Do you have Japanese friends? a conversation. -

SO 008 492 Moddrn Japanese Novels.In English: a Selected Bibliography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 109 045 SO 008 492 AUTHOR Beauchamp, Nancy. Junko TITLE Moddrn Japanese Novels.in English: A Selected Bibliography. Service Cebter Paper on Asian Studies, No. 7. INSTITUTION Ohio State Univ., Columbus. Service Center for Teachers of Asian Studies. PUB DATE May 74 NOTE 44p. AIAILABLE FROM Dr. Franklin Buchanan, Association for Asian Studies, Ohio State University, 29 West Woodruff Avenue-, Columbus, Ohio 43210 ($1.00) 'EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC -$1.95 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies; *Asian Studies; Elementary Secondary Education; Fiction; Humanities; *Interdisciplinary Approach; Literary Perspective; Literature Appreciation; *Literature Guides; Novels; Social Sciences; Social Studies; *Sociological Novels IDENTIFIERS *Japan IJ ABSTRACT Selected contemporary Japanese novels translated into English are compiled in this lbibliography as a guide for teachers interested in the possibilities offered by Japanese fiction. The bibliography acquaints teachers with available Japanese fiction, that can.be incorporated into social sciences or humanities courses to introduce Japan to students or to provide a comparative perspective. The selection, beginning with the first modern novel "Ukigumo," 1887-89, is limited to accessible full-length noyels with post-1945 translations, excluding short stories and fugitive works. The entries are arranged alphabetically by author, with his literary awards given first followed by an alphabetical listing of English titles of his works. The entry information for each title includes-the romanized Japanese title and original publication date, publications of the work, a short abstract, and major reviews. Included in the prefatory section are an overview of the milieu from which Japanese fiction has emerged; the scope of the contemporary period; and guides to new publications, abstracts, reviews, and criticisms and literary essays. -

Natsume Sōseki, the Greatest Novelist in Modern Japan 21St November – 18Th December 2013

Celebrating the 150th Anniversary of UK-Japan Academic Interaction Natsume Sōseki, the Greatest Novelist in Modern Japan 21st November – 18th December 2013 UCL Library Services and Tohoku University Library are holding the collaborative exhibition, "Natsume Sōseki, the Greatest Novelist in Modern Japan" to celebrate the 150th Anniversary of UK-Japan Academic Interaction. Tohoku University has a long tradition as a national university in Japan, and the library is one of the largest and well-stocked libraries. Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916) is the most famous and respected novelist in Japan. He stayed in England for two years as a Japanese government scholarship student, and studied English literature at UCL for a short period. Items on display are a part of the Natsume Sōseki Collection which Tohoku University library has as a rare and special collection, consisting of about 3,000 books that he collected and his extensive manuscripts. Natsume Sōseki’s Short Biography Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916) is not only the most eminent novelist, but also one of the pioneers of English literary studies in modern Japan. He was born in Edo (Tokyo). At that time, Japan had faced the series of revolutionary changes called the Meiji Restoration, aiming to rebuild itself into a modern and western style nation-state. The drastic reformations of social structure in Japan also greatly influenced Sōseki’s life and thoughts. His early concern was Chinese classic literature. But, in his school days, he had a great ambition to be a prominent figure internationally, and so entered the English department of Tokyo Imperial University where he was the second student majoring in English. -

Unbinding the Japanese Novel in English Translation

Department of Modern Languages Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki UNBINDING THE JAPANESE NOVEL IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION The Alfred A. Knopf Program, 1955 – 1977 Larry Walker ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Helsinki, for public examination in Auditorium XII University Main Building, on the 25th of September at 12 noon. Helsinki 2015 ISBN 978-951-51-1472-3 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-1473-0 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2015 ABSTRACT Japanese literature in English translation has a history of 165 years, but it was not until after the hostilities of World War II ceased that any single publisher outside Japan put out a sustained series of novel-length translations. The New York house of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. published thirty-four titles of Japanese literature in English translation in hardcover between the years 1955 to 1977. This “Program,” as it came to be called, was carried out under the leadership of Editor-in-Chief Harold Strauss (1907-1975), who endeavored to bring the then-active modern writers of Japan to the stage of world literature. Strauss and most of the translators who made this Program possible were trained in military language schools during World War II. The aim of this dissertation is to investigate the publisher’s policies and publishing criteria in the selection of texts, the actors involved in the mediation process and the preparation of the texts for market, the reception of the texts and their impact on the resulting translation profile of Japanese literature in America, England and elsewhere. -

Sosok Pengarang Dalam Novel Wagahai Wa Neko Dearu Karya Natsume Sōseki”

1 IR - PERPUSTAKAAN UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Nama Natsume Sōseki (夏目漱石) sudah pasti tidak asing didengar oleh telinga para pecinta sastra khususnya sastra Jepang. Prof. Donald Keene dalam pengantar bunga rampai sastra Jepang modern yang disusunnya, menyebut Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916) sebagai salah satu raksasa dalam sastra Jepang di zaman Meiji. Sebutan yang didapat oleh Natsume Sōseki juga bermacam-macam, antara lain penulis prosa Jepang terbaik, penulis roman terbesar, serta penghubung sastra Jepang klasik dan sastra modern. Sōseki juga merupakan tokoh yang menjulang dalam kehidupan intelektual zaman Meiji, sehingga tidak diragukan lagi bahwa Natsume Sōseki merupakan penulis Jepang terbesar. Nama Natsume Sōseki merupakan nama pena yang pertama kali digunakan Natsume Kinnosuke saat ia mulai menulis haiku. Sastrawan kelahiran Tokyo, Jepang ini memulai debutnya sebagai novelis dengan cerita pendeknya berjudul Wagahai wa Neko de Aru (吾輩は猫である). Dengan terbitnya karya tersebut, ia menjadi terkenal dan banyak digemari orang karena ceritanya yang mendapat sambutan yang luar biasa. Sōseki sendiri mulai dikenal pada era Meiji dengan karya-karyanya yang sebagian besar bergenre roman. Karya-karya Natsume Sōseki yang lain antara lain Botchan, Kokoro, Sorekara, Sanshiro, Mon, Yume Juya, dan masih banyak lagi. Melalui karya-karyanya, bisa dilihat bahwa Sōseki menganut aliran anti naturalisme dan menjadi salah satu pelopor aliran tersebut bersama dengan Akutagawa Ryunosuke. Kemunculannya yang membawa aliran anti naturalis SKRIPSI SOSOK PENGARANG DALAM … RETNOSARI 2 IR - PERPUSTAKAAN UNIVERSITAS AIRLANGGA dalam karyanya dengan cepat menjadi popular karena aliran anti naturalisme melukiskan keindahan dan meneropong kehidupan dan cita-cita manusia. Berlainan dengan naturalisme yang menggambarkan semua apa-adanya hingga bagian paling buruk dari kehidupan.