Guide to World Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

Japanese Literature Quiz Who Was the First Japanese Novelist to Win the Nobel Prize for Literature?

Japanese Literature Quiz Who was the first Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasunari Kawabata ② Soseki Natsume ③ Ryunosuke Akutagawa ④ Yukio Mishima Who was the first Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasunari Kawabata ② Soseki Natsume ③ Ryunosuke Akutagawa ④ Yukio Mishima Who was the second Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasushi Inoue ② Kobo Abe ③ Junichiro Tanizaki ④ Kenzaburo Oe Who was the second Japanese novelist to win the Nobel Prize for Literature? ① Yasushi Inoue ② Kobo Abe ③ Junichiro Tanizaki ④ Kenzaburo Oe What is the title of Soseki Natsume's novel, "Wagahai wa ( ) de aru [I Am a ___]"? ① Inu [Dog] ② Neko [Cat] ③ Saru [Monkey] ④ Tora [Tiger] What is the title of Soseki Natsume's novel, "Wagahai wa ( ) de aru [I Am a ___]"? ① Inu [Dog] ② Neko [Cat] ③ Saru [Monkey] ④ Tora [Tiger] Which hot spring in Ehime Prefecture is written about in "Botchan," a novel by Soseki Natsume? ① Dogo Onsen ② Kusatsu Onsen ③ Hakone Onsen ④ Arima Onsen Which hot spring in Ehime Prefecture is written about in "Botchan," a novel by Soseki Natsume? ① Dogo Onsen ② Kusatsu Onsen ③ Hakone Onsen ④ Arima Onsen Which newspaper company did Soseki Natsume work and write novels for? ① Mainichi Shimbun ② Yomiuri Shimbun ③ Sankei Shimbun ④ Asahi Shimbun Which newspaper company did Soseki Natsume work and write novels for? ① Mainichi Shimbun ② Yomiuri Shimbun ③ Sankei Shimbun ④ Asahi Shimbun When was Murasaki Shikibu's "Genji Monogatari [The Tale of Genji] " written? ① around 1000 C.E. ② around 1300 C.E. ③ around 1600 C.E. ④ around 1900 C.E. When was Murasaki Shikibu's "Genji Monogatari [The Tale of Genji] " written? ① around 1000 C.E. -

Literature and Film of the Weimar Republic (In English Translation) OLLI@Berkeley, Spring 2019 Mondays, April 1—29, 2019 (5 Weeks), 10:00 A.M

Instructor: Marion Gerlind, PhD (510) 430-2673 • [email protected] Literature and Film of the Weimar Republic (in English translation) OLLI@Berkeley, Spring 2019 Mondays, April 1—29, 2019 (5 weeks), 10:00 a.m. — 12:30 p.m. University Hall 41B, Berkeley, CA 94720 In this interactive seminar we shall read and reflect on literature as well as watch and discuss films of the Weimar Republic (1919–33), one of the most creative periods in German history, following the traumatic Word War I and revolutionary times. Many of the critical issues and challenges during these short 14 years are still relevant today. The Weimar Republic was not only Germany’s first democracy, but also a center of cultural experimentation, producing cutting-edge art. We’ll explore some of the most popular works: Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s musical play, The Threepenny Opera, Joseph von Sternberg’s original film The Blue Angel, Irmgard Keun’s bestseller The Artificial Silk Girl, Leontine Sagan’s classic film Girls in Uniform, Erich Maria Remarque’s antiwar novel All Quiet on the Western Front, as well as compelling poetry by Else Lasker-Schüler, Gertrud Kolmar, and Mascha Kaléko. Format This course will be conducted in English (films with English subtitles). Your active participation and preparation is highly encouraged! I recommend that you read the literature in preparation for our sessions. I shall provide weekly study questions, introduce (con)texts in short lectures and facilitate our discussions. You will have the opportunity to discuss the literature/films in small and large groups. We’ll consider authors’ biographies in the socio-historical background of their work. -

Soseki's Botchan Dango ' Label Tamanoyu Kaminoyu Yojyoyu , The

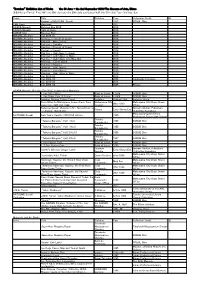

"Botchan" Exhibition List of Works the 30 June - the 2nd September 2018/The Museum of Arts, Ehime ※Exhibition Period First Half: the 30th Jun sat.-the 29th July sun/Latter Half: the 31th July Tue.- 2nd Sep. Sun Artist Title Piblisher Year Collection Credit ※ Portrait of NATSUME Soseki 1912 SOBUE Shin UME Kayo Botchans' 2017 ASADA Masashi Botchan Eye 2018' 2018 ASADA Masashi Cats at Dogo 2018 SOBUE Shin Botchan Bon' 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2018-01 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - White Heron 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Camellia 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi-Neko in Green 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko at Night 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko with Blue Sky 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Turner Island 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Pegasus 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Sabi -Neko 1 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Sabi -Neko 2 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko in White 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2013-03 2013 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2002-02 2002 Takahashi Collection MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2014-02 2014 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2006-04 2006 Private ASADA Masashi 'Botchan Eye 2018' Collaboration Materials 1 Yen Bill (2 Bills) Bank of Japan c.1916 SOBUE Shin 1 Yen Silver Coin (3 Coins) Bank of Japan c.1906 SOBUE Shin Iyotetsu Railway Ticket (Copy) Iyotetsu Original:1899 Iyotetsu Group From Mitsu to Matsuyama, Lower Class, Fare Matsuyama City Matsuyama City Dogo Onsen after 1950 3sen 5rin , 28th Oct.,1888 Tourism Office Natsume Soseki, Botchan 's Inn Yamashiroya is Iwanami Shoten, Publishers. -

Paradise Lost and Pullman's His Dark Materials

Mythic Rhetoric: Influence and Manipulation in Milton's Paradise Lost and Pullman's His Dark Materials Rhys Edward Pattimore A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Masters by Research Department of Interdisciplinary Studies MMU Cheshire 2015 1 Declaration I declare that this is my own work, that I have followed the code of academic good conduct and have sought, where necessary, advice and guidance on the proper presentation of my work. Printed Name: Signature: 2 Acknowledgments For my family and friends: without your love, support and patience I could not have hoped to achieve what I have. I love you all. To my tutors; I cannot thank you enough; I’m eternally grateful for your never-ending encouragement and invaluable assistance throughout the year. Finally, to the authors who have influenced my writing: their stories are my inspiration and without them, this simply would not have happened. 3 Contents Page - Abstract Page 5 - Note on Abbreviations Page 6 - Introduction Page 7 - Chapter One Page 26 - Chapter Two Page 43 - Chapter Three Page 78 - Conclusion Page 119 - Glossary of Rhetorical Terms Page 125 - Appendix: Quotations Page 129 - Bibliography Page 135 4 Abstract John Milton’s Paradise Lost and Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials are two grand feats of mythic storytelling. Through their compelling stories, reinforced by influential rhetoric, each possesses the ability to affect individuals who read them. These myths work to influence their audiences without the author’s own personal beliefs being forced upon them (such as Milton’s scathing condemnation of certain styles of poetry, or Pullman’s overtly critical view of Christianity). -

Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 Senecan Tragedy and Virgil's Aeneid: Repetition and Reversal Timothy Hanford Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/427 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by TIMOTHY HANFORD A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Classics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ©2014 TIMOTHY HANFORD All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Classics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ronnie Ancona ________________ _______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Dee L. Clayman ________________ _______________________________ Date Executive Officer James Ker Joel Lidov Craig Williams Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract SENECAN TRAGEDY AND VIRGIL’S AENEID: REPETITION AND REVERSAL by Timothy Hanford Advisor: Professor Ronnie Ancona This dissertation explores the relationship between Senecan tragedy and Virgil’s Aeneid, both on close linguistic as well as larger thematic levels. Senecan tragic characters and choruses often echo the language of Virgil’s epic in provocative ways; these constitute a contrastive reworking of the original Virgilian contents and context, one that has not to date been fully considered by scholars. -

Mathematical Circus & 'Martin Gardner

MARTIN GARDNE MATHEMATICAL ;MATH EMATICAL ASSOCIATION J OF AMERICA MATHEMATICAL CIRCUS & 'MARTIN GARDNER THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Washington, DC 1992 MATHEMATICAL More Puzzles, Games, Paradoxes, and Other Mathematical Entertainments from Scientific American with a Preface by Donald Knuth, A Postscript, from the Author, and a new Bibliography by Mr. Gardner, Thoughts from Readers, and 105 Drawings and Published in the United States of America by The Mathematical Association of America Copyright O 1968,1969,1970,1971,1979,1981,1992by Martin Gardner. All riglhts reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. An MAA Spectrum book This book was updated and revised from the 1981 edition published by Vantage Books, New York. Most of this book originally appeared in slightly different form in Scientific American. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 92-060996 ISBN 0-88385-506-2 Manufactured in the United States of America For Donald E. Knuth, extraordinary mathematician, computer scientist, writer, musician, humorist, recreational math buff, and much more SPECTRUM SERIES Published by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Committee on Publications ANDREW STERRETT, JR.,Chairman Spectrum Editorial Board ROGER HORN, Chairman SABRA ANDERSON BART BRADEN UNDERWOOD DUDLEY HUGH M. EDGAR JEANNE LADUKE LESTER H. LANGE MARY PARKER MPP.a (@ SPECTRUM Also by Martin Gardner from The Mathematical Association of America 1529 Eighteenth Street, N.W. Washington, D. C. 20036 (202) 387- 5200 Riddles of the Sphinx and Other Mathematical Puzzle Tales Mathematical Carnival Mathematical Magic Show Contents Preface xi .. Introduction Xlll 1. Optical Illusions 3 Answers on page 14 2. Matches 16 Answers on page 27 3. -

Trauma and Memory: an Artist in Turmoil

TRAUMA AND MEMORY: AN ARTIST IN TURMOIL By Angelos Koutsourakis Konrad Wolf’s Artist Films Der nackte Mann auf dem Sportplatz (The Naked Man on the Sports Field, 1973) is one of Konrad Wolf’s four artist films. Like Goya (1971), Solo Sunny (1978), and Busch singt (Busch Sings, 1982)—his six-part documentary about the German singer and actor Ernst Busch, The Naked Man on the Sports Field focuses on the relationship between art and power. In Goya, Wolf looks at the life of the renowned Spanish painter—who initially benefited from the protection of the Spanish king and the Catholic church—in order to explore the role of the artist in society, as well as issues of artistic independence from political powers. In Solo Sunny, he describes a woman’s struggle for artistic expression and self-realization in a stultifying world that is tainted by patriarchal values; Sunny’s search is simultaneously a search for independence and a more fulfilling social role. Both films can Film Library • A 2017 DVD Release by the DEFA be understood as a camouflaged critique of the official and social pressures faced by East German artists. The Naked Man on the Sports Field can be seen this way as well, and simultaneously explores questions of trauma and memory. The film tells the story of Herbert Kemmel (played by Kurt Böwe), an artist uncomfortable with the dominant understanding of art in his country. Kemmel is a sculptor in turmoil, insofar as he seems to feel alienated from his social environment, in which people do not understand his artistic works. -

Dares Phrygius' De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological Commentary and Translation

Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Dares Phrygius' De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological Commentary and Translation Jonathan Cornil Scriptie voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van Master in de Taal- en letterkunde (Latijn – Engels) 2011-2012 Promotor: Prof. Dr. W. Verbaal ii Table of Contents Table of Contents iii Foreword v Introduction vii Chapter I. De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological and Historical Comments 1 A. Dares and His Historia: Shrouded in Mystery 2 1. Who Was ‘Dares the Phrygian’? 2 2. The Role of Cornelius Nepos 6 3. Time of Origin and Literary Environment 9 4. Analysing the Formal Characteristics 11 B. Dares as an Example of ‘Rewriting’ 15 1. Homeric Criticism and the Trojan Legacy in the Middle Ages 15 2. Dares’ Problematic Connection with Dictys Cretensis 20 3. Comments on the ‘Lost Greek Original’ 27 4. Conclusion 31 Chapter II. Translations 33 A. Translating Dares: Frustra Laborat, Qui Omnibus Placere Studet 34 1. Investigating DETH’s Style 34 2. My Own Translations: a Brief Comparison 39 3. A Concise Analysis of R.M. Frazer’s Translation 42 B. Translation I 50 C. Translation II 73 D. Notes 94 Bibliography 95 Appendix: the Latin DETH 99 iii iv Foreword About two years ago, I happened to be researching Cornelius Nepos’ biography of Miltiades as part of an assignment for a class devoted to the study of translating Greek and Latin texts. After heaping together everything I could find about him in the library, I came to the conclusion that I still needed more information. So I decided to embrace my identity as a loyal member of the ‘Internet generation’ and began my virtual journey through the World Wide Web in search of articles on Nepos. -

Author, Title Price Notes

Contact: Suriya Prabhakar [email protected] Hey Germanists/Linguists, I’m Suriya, a recent German graduate from Teddy Hall, and I’m looking to sell most of my books that I bought firsthand during my degree. All the books are in extremely good condition, and some of them barely used. You may find the occasional annotation but it will be in pencil and easily erasable (except poetry books where specified). All these prices are half the original price or less (based on Amazon), so I can guarantee you will be saving loads of money (unlike me in first year) on books that you probably won’t use after your degree! They will be sold on a first come first served basis – all you need to do is email me as soon as you’ve decided which ones you want! I’m happy to answer any questions you may have, and am willing to provide details/photos of books if needed. Do get in touch at: [email protected] All the best, Suriya Author, Title Price Notes Georg Kaiser, Von morgens bis 50p Prelims mitternachts (Reclam) Frank Wedekind, Frühlings Erwachen 50p Prelims Arthur Schnitzler, Liebelei (Reclam) 50p Prelims Deutsche Lyrik (Eine Anthologie) £4 Prelims; pencil annotations on set poems Mann, Mario und der Zauberer (Fischer) £3 Prelims Brecht, Die Maßnahme £2 Prelims Erich Maria Remarque, Im Westen nichts £3 Prelims Neues Hartmann von Aue, Gregorius (Reclam) £2 Prelims/Medieval Wolfram von Eschenbach, Parzival £7 VI/IX Medieval; very slight tear on Band 1 + 2 (Reclam) front cover of Band 1 (does not impact text) Parzival Translation (Penguin -

Historie a Vývoj Baletní Scény Mariinského Divadla

Univerzita Hradec Králové Pedagogická fakulta Katedra ruského jazyka a literatury Historie a vývoj baletní scény Mariinského divadla Diplomová práce Autor: Bc. Andrea Plecháčová Studijní program: N7504 – Učitelství pro střední školy Studijní obor: Učitelství pro střední školy – základy společenských věd Učitelství pro střední školy – ruský jazyk a literatura Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jaroslav Sommer Oponent práce: prof. PhDr. Ivo Pospíšil, DrSc. Hradec Králové 2020 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracovala (pod vedením vedoucího diplomové práce) samostatně a uvedla jsem všechny použité prameny a literaturu. V Hradci Králové dne … ………………………… Bc. Andrea Plecháčová Poděkování Ráda bych poděkovala svému vedoucímu panu Mgr. Jaroslavu Sommerovi za odborné vedení a cenné rady při vypracovávání diplomové práce. Dále děkuji paní Mgr. Jarmile Havlové za pomoc při korektuře gramatické stránky práce. Anotace PLECHÁČOVÁ, Andrea. Historie a vývoj baletní scény Mariinského divadla. Hradec Králové: Pedagogická fakulta Univerzity Hradec Králové, 2020. 66 s. Diplomová práce. Práce se zaměřuje na historii a vývoj baletní scény Mariinského divadla po současnost. Věnuje se také nejslavnějším osobnostem a inscenacím baletní scény Mariinského divadla v Petrohradě. Klíčová slova: balet, divadlo, Petrohrad, umění, Leningrad, Kirovovo divadlo opery a baletu, Mariinské divadlo. Annotation PLECHÁČOVÁ, Andrea. History and Development of the Mariinsky Ballet. Hradec Králové: Faculty of Education, University of Hradec Králové, 2020. 66 pp. Diploma Dissertation Degree Thesis. The thesis focuses on the history and development of the ballet stage of the Mariinsky Theatre up to the present. It is also dedicated to the most outstanding personalities and stagings of the Mariinsky Theatre in Petersburg. Keywords: ballet, theatre, Saint Petersburg, art, Leningrad, Kirov Theatre, The Mariinsky Theatre. -

Volume 1 a Collection of Essays Presented at the First Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on C.S

Inklings Forever Volume 1 A Collection of Essays Presented at the First Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on C.S. Lewis & Article 1 Friends 1997 Full Issue 1997 (Volume 1) Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1997) "Full Issue 1997 (Volume 1)," Inklings Forever: Vol. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol1/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inklings Forever by an authorized editor of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INKLINGS FOREVER A Collection of Essays Presented at tlte First FRANCES WHITE EWBANK COLLOQUIUM on C.S. LEWIS AND FRIENDS II ~ November 13-15, 1997 Taylor University Upland, Indiana ~'...... - · · .~ ·,.-: :( ·!' '- ~- '·' "'!h .. ....... .u; ~l ' ::-t • J. ..~ ,.. _r '· ,. 1' !. ' INKLINGS FOREVER A Collection of Essays Presented at the Fh"St FRANCES WHITE EWBANK COLLOQliTUM on C.S. LEWIS AND FRIENDS Novem.ber 13-15, 1997 Published by Taylor University's Lewis and J1nends Committee July1998 This collection is dedicated to Francis White Ewbank Lewis scholar, professor, and friend to students for over fifty years ACKNOWLEDGMENTS David Neuhauser, Professor Emeritus at Taylor and Chair of the Lewis and Friends Committee, had the vision, initiative, and fortitude to take the colloquium from dream to reality. Other committee members who helped in all phases of the colloquium include Faye Chechowich, David Dickey, Bonnie Houser, Dwight Jessup, Pam Jordan, Art White, and Daryl Yost.