Wear and Tear: the Threads of My Life by Tracy Tynan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

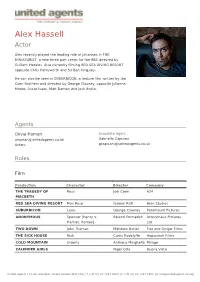

Alex Hassell Actor

Alex Hassell Actor Alex recently played the leading role of Johannes in THE MINIATURIST, a new three part series for the BBC directed by Guillem Morales. Also currently filming RED SEA DIVING RESORT opposite Chris Hemsworth and Sir Ben Kingsley. He can also be seen in SUBURBICON, a feature film written by the Coen Brothers and directed by George Clooney, opposite Julianne Moore, Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon and Josh Brolin. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE TRAGEDY OF Ross Joel Coen A24 MACBETH RED SEA DIVING RESORT Max Rose Gideon Raff Bron Studios SUBURBICON Louis George Clooney Paramount Pictures ANONYMOUS Spencer [Henry V, Roland Emmerich Anonymous Pictures Hamlet, Romeo] Ltd TWO DOWN John Thomas Matthew Butler Fizz and Ginger Films THE SICK HOUSE Nick Curtis Radclyffe Hopscotch Films COLD MOUNTAIN Orderly Anthony Minghella Mirage CALENDER GIRLS Nigel Cole Buena Vista United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Television Production Character Director Company COWBOY BEPOP Vicious Alex Garcia Lopez Netflix THE MINATURIST Johannes Guillem Morales BBC SILENT WITNESS Simon Nick Renton BBC WAY TO GO Phillip Catherine Morshead BBC BIG THUNDER Abel White Rob Bowman ABC LIFE OF CRIME Gary Nash Jim Loach Loc Film Productions HUSTLE Viscount Manley John McKay BBC A COP IN PARIS Piet Nykvist Charlotte Sieling Atlantique Productions -

N.F. Simpson and “The Theatre of the Absurd”

Platform , Vol. 3, No. 1 N.F. Simpson and “The Theatre of the Absurd” Neema Parvini (Royal Holloway, University of London) In 1958, in the Observer , Kenneth Tynan wrote of “a dazzling new playwright,” with his inimitable enthusiasm he declared: “I am ready to burn my boats and promise [that] N.F. Simpson [is] the most gifted comic writer the English stage has discovered since the war” (Tynan 210). Now, in 2008, despite a recent West End revival, 1 few critics would cite Simpson at all and debates regarding the “most gifted comic writer” of the English stage would invariably be centred on Tom Stoppard, Joe Orton, Samuel Beckett or, for those with a more morose sense of humour, Harold Pinter. Part of the reason for Simpson’s critical decline can be put down to protracted periods of silence; after his run of critically and commercially successful plays with The English Stage Company, 2 Simpson only produced two further full length plays: The Cresta Run (1965) and Was He Anyone? (1972). Of these, the former was poorly received and the latter only reached the fringe theatre. 3 As Stephen Pile recently put it, “in 1983, Simpson himself vanished” with no apparent fixed address. The other reason that may be cited is that, more than any other British writer of his time, Simpson was associated with “The Theatre of the Absurd.” As the vogue for the style died out in London, Simpson’s brand of Absurdism simply went out of fashion. John Russell Taylor offers perhaps the most scathing version of that argument: “whether one likes or dislikes N.F. -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchases and gifts, 1991-2000 Processed by Katherine Mosley, 1993-2000 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Biographical Sketch Playwright Tom Stoppard was born Tomas Straussler in Zlin, Czechoslovakia, on July 3, 1937. However, he lived in Czechoslovakia only until 1939, when his family moved to Singapore. Stoppard, his mother, and his older brother were evacuated to India shortly before the Japanese invasion of Singapore in 1941; his father, Eugene Straussler, remained behind and was killed. In 1946, Stoppard's mother, Martha, married British army officer Kenneth Stoppard and the family moved to England, eventually settling in Bristol. Stoppard left school at the age of seventeen and began working as a journalist, first with the Western Daily Press (1954-58) and then with the Bristol Evening World (1958-60). -

Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal

About Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/about/ Archive: http://www.the-criterion.com/archive/ Contact Us: http://www.the-criterion.com/contact/ Editorial Board: http://www.the-criterion.com/editorial-board/ Submission: http://www.the-criterion.com/submission/ FAQ: http://www.the-criterion.com/fa/ ISSN 2278-9529 Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal Bi-Monthly Refereed and Indexed Open Access eJournal www.galaxyimrj.com The Criterion: An International Journal in English Vol. 8, Issue-III, June 2017 ISSN: 0976-8165 Tragic Vision Represented in the Plays of John Osborne Sunil N. Wathore Asst. Prof. & HoD. English Arts & Science College, Pulgaon, Dist. Wardha, Rashtrasant Tukadoji Maharaj Nagpur University, Nagpur. Article History: Submitted-18/05/2017, Revised-11/06/2017, Accepted-23/06/2017, Published-05/07/2017. Abstract: John James Osborne, an English playwright, ex-journalist, screenwriter and actor, known for his excoriating prose and intense critical stance towards established social and political norms was born on 12th December, 1929 in Fulham, London. Osborne’s tragic vision arises out of perception of the problems of existence in the face of nothingness. Osborne’s heroes live in the world of nothingness which is resulted due to the prevailing customs and traditions and other evil forces, cause a rebellion against them. A full length study of Osborne’s tragic vision of life, that emerges out of his tragedies would not only add to the greater appreciation of Osborne but also help to assess his achievement and assign the rightful place to Osborne in the history of Modern British Drama. Osborne’s artistic vision seems to have been conditioned and shaped by two important forces -those are heredity and environment on one side and his own personal experiences on the other. -

The Dramatic World Harol I Pinter

THE DRAMATIC WORLD HAROL I PINTER RITUAL Katherine H. Bnrkman $8.00 THE DRAMATIC WORLD OF HAROLD PINTER By Katherine H. Burkman The drama of Harold Pinter evolves in an atmosphere of mystery in which the surfaces of life are realistically detailed but the pat terns that underlie them remain obscure. De spite the vivid naturalism of his dialogue, his characters often behave more like figures in a dream than like persons with whom one can easily identify. Pinter has on one occasion admitted that, if pressed, he would define his art as realistic but would not describe what he does as realism. Here he points to what his audience has often sensed is distinctive in his style: its mixture of the real and sur real, its exact portrayal of life on the surface, and its powerful evocation of that life that lies beneath the surface. Mrs. Burkman rejects the contention of some Pinter critics that the playwright seeks to mystify and puzzle his audience. To the contrary, she argues, he is exploring experi ence at levels that are mysterious, and is a poetic rather than a problem-solving play wright. The poetic images of the play, more over, Mrs. Burkman contends, are based in ritual; and just as the ancient Greeks at tempted to understand the mysteries of life by drawing upon the most primitive of reli gious rites, so Pinter employs ritual in his drama for his own tragicomic purposes. Mrs. Burkman explores two distinct kinds of ritual that Pinter develops in counter point. His plays abound in those daily habit ual activities that have become formalized as ritual and have tended to become empty of meaning, but these automatic activities are set in contrast with sacrificial rites that are loaded with meaning, and force the charac ters to a painful awareness of life from which their daily routines have served to protect them. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. I witnessed the demonstrations against Terrence McNally’s play, Corpus Christi, in 1999 at Edinburgh’s Bedlam Theatre, the home of the University’s student theatre company. But these protests were not taken seriously by any- one I knew: acknowledged as a nuisance, certainly, but also judged to be very good for publicity in the competitive Festival fringe. 2. At ‘How Was it for You? British Theatre Under Blair’, a conference held in London on 9 December 2007, the presentations of directors Nicholas Hytner, Emma Rice and Katie Mitchell, writers Mark Lawson, Kwame Kwei-Armah, Tanika Gupta and Mark Ravenhill, and actor and Equity Rep Malcolm Sinclair all included reflection upon issues of censorship, the policing of per- formance or indirect forms of constraint upon content. Ex-Culture Minister Tessa Jowell’s opening presentation also discussed censorship and the closure of Behzti. 3. Andrew Anthony, ‘Amsterdammed’, The Observer, 5 December 2004; Alastair Smart, ‘Where Angels Fear to Tread’, The Sunday Telegraph, 10 December 2006. 4. Christian Voice went on to organise protests at the theatre pro- duction’s West End venue and then throughout the country on a national tour. ‘Springer protests pour in to BBC’, BBC News, 6 January 2005, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/tv_and_radio/4152433.stm [accessed 1 August 2007]. 5. Angelique Chrisafis, ‘Loyalist Paramilitaries Drive Playwright from His Home’, The Guardian, 21 December 2005. 6. ‘Tate “Misunderstood” Banned Work’, BBC News, 26 September 2005, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/entertainment/arts/4281958.stm [accessed 1 August 2007]; for discussion of the Bristol Old Vic’s decision, see Ian Shuttleworth, ‘Prompt Corner’, Theatre Record, 25.23, 6 December 2005, pp. -

In Spite of History? New Leftism in Britain 1956 - 1979

In Spite of History? New Leftism in Britain 1956 - 1979 Thomas Marriott Dowling Thesis Presented for the Degree of PhD Department of History University of Sheffield August 2015 ii iii Contents Title page p. i Contents p. iii Abstract p. vi Introduction p. 1 On the Trail of the New Left p. 5 Rethinking New Leftism p. 12 Methodology and Structure p. 18 Chapter One Left Over? The Lost World of British New Leftism p. 24 ‘A Mood rather than a Movement’ p. 30 A Permanent Aspiration p. 33 The Antinomies of British New Leftism p. 36 Between Aspiration and Actuality p. 39 The Aetiology of British New Leftism p. 41 Being Communist p. 44 Reasoning Rebellion p. 51 Universities and Left Review p. 55 Forging a Movement p. 58 CND p. 63 Conclusion p. 67 iv Chapter Two Sound and Fury? New Leftism and the British ‘Cultural Revolt’ of the 1950s p. 69 British New Leftism’s ‘Moment of Culture’? p. 76 Principles behind New Leftism’s Cultural Turn p. 78 A British Cultural Revolt? p. 87 A New Left Culture? p. 91 Signifying Nothing? p. 96 Conclusion p. 99 Chapter Three Laureate of New Leftism? Dennis Potter’s ‘Sense of Vocation’ p. 102 A New Left ‘Mood’ p. 108 The Glittering Coffin p. 113 A New Left Politician p. 116 The Uses of Television p. 119 History and Sovereignty p. 127 Common Culture and ‘Occupying Powers’ p. 129 Conclusion p. 133 Chapter Four Imagined Revolutionaries? The Politics and Postures of 1968 p. 135 A Break in the New Left? p. -

From Pleasure to Menace: Noel Coward, Harold Pinter, and Critical Narratives

Fall 2009 41 From Pleasure to Menace: Noel Coward, Harold Pinter, and Critical Narratives Jackson F. Ayres For many, if not most, scholars of twentieth century British drama, the playwrights Noel Coward and Harold Pinter belong in entirely separate categories: Coward, a traditional, “drawing room dramatist,” and Pinter, an angry revolutionary redefining British theatre. In short, Coward is often used to describe what Pinter is not. Yet, this strict differentiation is curious when one considers how the two playwrights viewed each other’s work. Coward frequently praised Pinter, going so far as to christen him as his successor in the use of language on the British stage. Likewise, Pinter has publicly stated his admiration of Coward, even directing a 1976 production of Coward’s Blithe Spirit (1941). Still, regardless of their mutual respect, the placement of Coward and Pinter within a shared theatrical lineage is, at the very least, uncommon in the current critical status quo. Resistance may reside in their lack of overt similarities, but likely also in the seemingly impenetrable dividing line created by the premiere of John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger on May 8, 1956. In his book, 1956 and All That (1999), Dan Rebellato convincingly argues that Osborne’s play created such a critical sensation that eventually “1956 becomes year zero, and time seems to flow both forward and backward from it,” giving the impression that “modern British theatre divides into two eras.”1 Coward contributed to this partially generational divide by frequently railing against so-called New Movement authors, particularly Samuel Beckett and Eugene Ionesco, for being self-important and tedious. -

Drama and Cultural Transfer: John Osborne in Vienna”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES Diplomarbeit Titel der Diplomarbeit “Drama and Cultural Transfer: John Osborne in Vienna” Verfasserin Maria Kasser Angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. Phil.) Wien, im August 2008 Studienzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 190 344 313 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Lehramtstudium, UF Englisch, UF Geschichte, Sozialkunde, Polit. Bildung Betreuer: o. Univ. Prof. Dr. Ewald Mengel ii iii Hinweis Diese Diplomarbeit hat nachgewiesen, dass die betreffende Kandidatin befähigt ist, wissenschaftliche Themen selbständig sowie inhaltlich und methodisch vertretbar zu bearbeiten. Da die Korrekturen der/des Beurteilenden nicht eingetragen sind und das Gutachten nicht beiliegt, ist daher nicht erkenntlich, mit welcher Note diese Arbeit abgeschlossen wurde. Das Spektrum reicht von sehr gut bis genügend. Es wird gebeten, diesen Hinweis bei der Lektüre zu beachten. Hiermit bestätige ich diese Arbeit nach bestem Wissen und Gewissen selbständig verfasst und die Regeln der wissenschaftlichen Praxis eingehalten zu haben. iv v Danksagung An dieser Stelle möchte ich mich bei all jenen bedanken, die mich während meines Studiums an der Universität Wien unterstützt haben: Ich danke allen meinen Professoren an der Universität Wien. Im Besonderen natürlich Dr. Ewald Mengel , dem ich dieses interessante Thema zu verdanken habe, und der mich in der Diplomarbeitsphase tatkräftig unterstützt hat. Bei meinen Eltern, Josef und Veronika Kasser , dafür, dass sie mir das Studium ermöglicht und immer an mich geglaubt haben. Bei meiner Schwester Johanna , die mit ihrem Ehrgeiz und ihrer Zielstrebigkeit immer ein Vorbild für mich war. Bei meinem Bruder Jürgen , für seine Gelassenheit, die sich auch auf mich übertragen hat. -

Talking out of Tune

Talking Out of Tune Remembering British Theatre 1944-56 Kate Lucy Harris Ph.D. School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics University of Sheffield December 2008 1 Summary of Thesis This thesis explores how British Theatre represented and reacted to cultural and social changes between 1944 and 1956. It is closely linked to the oral history strand of the AHRC University of Sheffield British Library Theatre Archive Project <http://www.bl.ukltheatrearchive>. The five chapters focus on distinct subject areas in order to explore the vibrant diversity of the period. However, they are united by an overarching narrative which seeks to consider the relationship between memory and history. The first chapter is based on the oral history strand. It explores the different ways in which the Project's methodology has shaped both the interviewee testimony and my own research. Chapter 2 focuses on the changing historical perceptions of the popular West End plays of the day. Case studies of plays are used to compare the responses of audiences and critics in the 1940s and 50s, with the critical commentaries that surround the plays and playwrights today. The third chapter explores the relationship between BBC television drama and theatre. It assesses the impact that cross fertilisation had on both media by examining plays, productions and policies. Chapters 4 and 5 focus on two of the theatre companies of the period - Theatre Workshop and the Old Vic Theatre Company. Chapter 4 explores the impact that Theatre Workshop's early years as a touring group had on the development of the company. It draws on new oral history testimonies from former company members who joined the group in the 1940s and early 50s. -

Playboy Magazine Collection an Inventory

1 Playboy Magazine Collection An Inventory Creator: Hefner, Hugh (1926-2017) Title: Playboy Magazine Collection Dates: 1955-2018 Abstract: This collection consists of issues of Playboy and OUI magazines ranging from December 1955-June 2018. Playboy is unique among other erotic magazines of its time for its role as a purveyor of culture through political commentary, literature, and interviews with prominent activists, politicians, authors, and artists. The bulk of the collection dates from the 1960s-1970s and includes articles and interviews related to political debates such as the Cold War, Communism, Vietnam, the Civil Rights Movement, second-wave feminism, LGBTQ rights, and the depiction and consumption of the body. Researchers studying American Culture in the 1960s/70s, Gender & Sexuality, History of Advertising, and History of Photography will find this material of particular interest. Extent: 15 boxes, 6.25 linear feet Language: English Repository: Drew University Library, Madison NJ Biographical and History Note: Hugh Hefner, (April 9, 1926 – September 27, 2017), the founder and editor-in-chief of Playboy magazine, was known as a free speech activist, philanthropist, and proponent of sexual freedom. He founded Playboy magazine in 1953 with $1,000 seed money provided by his mother, Grace Hefner, a devout Methodist. The magazine quickly became known for its subversive visual, literary, and political content. Playboy is unique among other erotic magazines of the same time period for its role as a purveyor of culture through political commentary, literature, and interviews with prominent activists, politicians, authors, and artists. As a lifestyle magazine, Playboy curated and commodified the image of the modern bachelor of leisure. -

The Winding Road to King's Reach

The Winding Road to King’s Reach by Richard Findlater (1977) The vision of the National Theatre has hovered Henry Irving, who speaking before a Social hazily above the British stage for over a Science Congress – eloquently championed century. Continental examples showed that the the National cause in 1878 (though he did vision could be turned into a reality: France has not share Arnold’s vision). This was the year had a National Theatre since 1680; Denmark, in which he inaugurated at the Lyceum a Sweden and Austria have had theirs for managerial regime that seemed, to the late some two hundred years. Yet the first record Victorian era, to be a kind of National Theatre of a specific British project dates from no in itself. Its collapse in the 1890s under severe earlier than 1848, when a London publisher – economic pressures perhaps helped to point Effingham Wilson – prompted by the purchase the need for an endowed, exemplary theatre of in 1847 of Shakespeare’s birthplace for the an entirely different kind from the speculative nation – issued two pamphlets proposing ‘A show business of even the most talented House for Shakespeare’, in public ownership, and enlightened of star soloists in private where the works of ‘the world’s greatest moral management. teacher’ would be constantly performed. Several eminent Victorians – including two of The substantial history of the National Theatre the century’s most successful playwrights, Lord movement begins in 1904, the year before Lytton and Tom Taylor – later spoke up for the Irving’s death, when the critic William Archer ideals of a National Theatre.