1 This Is One of the Great Shakespeare Films. There Are Miscalculations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laura Morrod Resume

LAURA MORROD – Editor FATE Director: Lisa James Larsson. Producer: Macdara Kelleher. Starring: Abigail Cowen, Danny Griffin and Hannah van der Westhuysen. Archery Pictures / Netflix. LOVE SARAH Director: Eliza Schroeder. Producer: Rajita Shah. Starring: Grace Calder, Rupert Penry-Jones, Bill Paterson and Celia Imrie. Miraj Films / Neopol Film / Rainstar Productions. THE LAST KINGDOM (Series 4) Director: Sarah O’Gorman. Producer: Vicki Delow. Starring: Alexander Dreymon, Ian Hart, David Dawson and Eliza Butterworth. Carnival Film & Television / Netflix. THE FEED Director: Jill Robertson. Producer: Simon Lewis. Starring: Guy Burnet, Michelle Fairlye, David Thewlis and Claire Rafferty. Amazon Studios. ORIGIN Director: Mark Brozel. Executive Producers: Rob Bullock, Andy Harries and Suzanne Mackie. Producer: John Phillips. Starring: Tom Felton, Philipp Christopher and Adelayo Adedayo. Left Bank Pictures. THE GOOD KARMA HOSPITAL 2 Director: Alex Winckler. Producer: John Chapman. Starring: Amanda Redman, Amrita Acharia and Neil Morrissey. Tiger Aspect Productions. THE BIRD CATCHER Director: Ross Clarke. Producers: Lisa Black, Leon Clarance and Ross Clarke. Starring: August Diehl, Sarah-Sofie Boussnina and Laura Birn. Motion Picture Capital. BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN: IN HIS OWN WORDS Director: Nigel Cole. Producer: Des Shaw. Starring: Bruce Springsteen. Lonesome Pine Productions. 4929 Wilshire Blvd., Ste. 259 Los Angeles, CA 90010 ph 323.782.1854 fx 323.345.5690 [email protected] HUMANS (Series 2) Director: Mark Brozel. Producer: Paul Gilbert. Starring: Gemma Chan, Colin Morgan and Emily Berrington. Kudos Film and Television. AFTER LOUISE Director: David Scheinmann. Producers: Fiona Gillies, Michael Muller and Raj Sharma. Starring: Alice Sykes and Greg Wise. Scoop Films. DO NOT DISTURB Director: Nigel Cole. Producer: Howard Ella. Starring: Catherine Tate, Miles Jupp and Kierston Wareing. -

1 Ken Clarke

KEN CLARKE - MY PROFESSIONAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY When I left junior school at the age of twelve my plastering career started at the well known building Arts & Craft Secondary School, ‘Christopher Wren’, and from this early age I was particularly interested in fibrous plastering. It was a known fact that, of a class of 16, two of the pupils, after four years of schooling, would start their training at a major film studio. I passed my GCE in Building Craft, Paintwork and Plasterwork (copy 1 attached) and was one of the lucky two to be chosen to start training at Shepperton Studios. This was my first achievement (copy 2 – letter of engagement, 9 June 1964, attached). I started Shepperton Studios in the plastering Dept on 22 June 1964 under conditions of a six-month probationary period and a further 4 and half years. During this five-year apprenticeship, I was to do through the block release system, eight weeks at work and two weeks at Art & Craft College ‘Lime Grove’. At the end of five years I was awarded my basic and final City and Guilds in plastering (basic June 1966 and final June 1968 – copies 3 and 4 attached). This was a big achievement for any young man – for me; it was the beginning of a big career. After my five years I was presented with one of the very last certificates of apprenticeship offered by the ‘Film Industry Training Apprenticeship Council’. Thus, my apprenticeship came to an end. (Letter of thanks and delivery of my deeds and certificate 1 June 1969. -

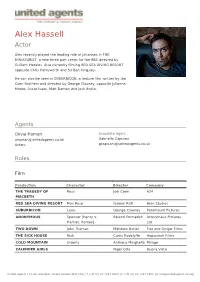

Alex Hassell Actor

Alex Hassell Actor Alex recently played the leading role of Johannes in THE MINIATURIST, a new three part series for the BBC directed by Guillem Morales. Also currently filming RED SEA DIVING RESORT opposite Chris Hemsworth and Sir Ben Kingsley. He can also be seen in SUBURBICON, a feature film written by the Coen Brothers and directed by George Clooney, opposite Julianne Moore, Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon and Josh Brolin. Agents Olivia Homan Associate Agent [email protected] Gabriella Capisani Actors [email protected] Roles Film Production Character Director Company THE TRAGEDY OF Ross Joel Coen A24 MACBETH RED SEA DIVING RESORT Max Rose Gideon Raff Bron Studios SUBURBICON Louis George Clooney Paramount Pictures ANONYMOUS Spencer [Henry V, Roland Emmerich Anonymous Pictures Hamlet, Romeo] Ltd TWO DOWN John Thomas Matthew Butler Fizz and Ginger Films THE SICK HOUSE Nick Curtis Radclyffe Hopscotch Films COLD MOUNTAIN Orderly Anthony Minghella Mirage CALENDER GIRLS Nigel Cole Buena Vista United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Television Production Character Director Company COWBOY BEPOP Vicious Alex Garcia Lopez Netflix THE MINATURIST Johannes Guillem Morales BBC SILENT WITNESS Simon Nick Renton BBC WAY TO GO Phillip Catherine Morshead BBC BIG THUNDER Abel White Rob Bowman ABC LIFE OF CRIME Gary Nash Jim Loach Loc Film Productions HUSTLE Viscount Manley John McKay BBC A COP IN PARIS Piet Nykvist Charlotte Sieling Atlantique Productions -

Completeandleft Felix ,Adler ,Educator ,Ethical Culture Ferrán ,Adrià ,Chef ,El Bulli FA,F

MEN WOMEN 1. FA Frankie Avalon=Singer, actor=18,169=39 Fiona Apple=Singer-songwriter, musician=49,834=26 Fred Astaire=Dancer, actor=30,877=25 Faune A.+Chambers=American actress=7,433=137 Ferman Akgül=Musician=2,512=194 Farrah Abraham=American, Reality TV=15,972=77 Flex Alexander=Actor, dancer, Freema Agyeman=English actress=35,934=36 comedian=2,401=201 Filiz Ahmet=Turkish, Actress=68,355=18 Freddy Adu=Footballer=10,606=74 Filiz Akin=Turkish, Actress=2,064=265 Frank Agnello=American, TV Faria Alam=Football Association secretary=11,226=108 Personality=3,111=165 Flávia Alessandra=Brazilian, Actress=16,503=74 Faiz Ahmad=Afghan communist leader=3,510=150 Fauzia Ali=British, Homemaker=17,028=72 Fu'ad Aït+Aattou=French actor=8,799=87 Filiz Alpgezmen=Writer=2,276=251 Frank Aletter=Actor=1,210=289 Frances Anderson=American, Actress=1,818=279 Francis Alexander+Shields= =1,653=246 Fernanda Andrade=Brazilian, Actress=5,654=166 Fernando Alonso=Spanish Formula One Fernanda Andrande= =1,680=292 driver.=63,949=10 France Anglade=French, Actress=2,977=227 Federico Amador=Argentinean, Actor=14,526=48 Francesca Annis=Actress=28,385=45 Fabrizio Ambroso= =2,936=175 Fanny Ardant=French actress=87,411=13 Franco Amurri=Italian, Writer=2,144=209 Firoozeh Athari=Iranian=1,617=298 Fedor Andreev=Figure skater=3,368=159 ………… Facundo Arana=Argentinean, Actor=59,952=11 Frickin' A Francesco Arca=Italian, Model=2,917=177 Fred Armisen=Actor=11,503=68 Frank ,Abagnale ,Criminal ,Catch Me If You Can François Arnaud=French Canadian actor=9,058=86 Ferhat ,Abbas ,Head of State ,President of Algeria, 1962-63 Fábio Assunção=Brazilian actor=6,802=99 Floyd ,Abrams ,Attorney ,First Amendment lawyer COMPLETEandLEFT Felix ,Adler ,Educator ,Ethical Culture Ferrán ,Adrià ,Chef ,El Bulli FA,F. -

James Thurber

James Thurber The Macbeth murder mystery “It was a stupid mistake to make," said the American woman I had met at my hotel in the English lake country, “but it was on the counter with the other Penguin books - the little sixpenny ones, you know; with the paper covers - and 1 supposed of. course it was a detective story All the others were detective stories. I‟d read all the others, .So I bought this one without really looking at it carefully. You can imagine how mad I was when I found it was Shakespeare." I murmured something sympathetically." 1 don't see why the Penguin-books people had to get out Shakespeare plays in the sane size and everything as the detective stories," went on my companion. “I think they have different colored jackets," I said. "Well, I didn't notice that," she said. "Anyway, I got real comfy in bed that night and all ready to read a good mystery story and here I had 'The Tragedy of Macbeth” – a book for high school students. Like „Ivanhoe,‟” “Or „Lorne Doone.‟” I said.. "Exactly," said the American lady. "And I was just crazy for a good Agatha Christie, or something. Hercule Poirot is my favorite detective." “Is he the rabbity one?" I asked. "Oh, no," said my crime- fiction expert. "He's the Belgian one. You're thinking of Mr. Pinkerton, the one that helps Inspector Bull. He's good, too." Over her second cup of tea my companion began to tell the plot of a detective story that had fooled her completely - it seems it was the old family doctor all the time. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Seven Ladies Macbeth

Seven Ladies Macbeth by Michael Bettencourt 67 Highwood Terrace #2, Weehawken NJ 07086 201-770-0770 • 347-564-9998 • [email protected] http://www.m-bettencourt.com Copyright © by Michael Bettencourt Offered under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ DESCRIPTION What came before Lady Macbeth became Lady Macbeth? CHARACTERS • GRUOCH (later, Lady Macbeth) • ELFRIDA (mother of Lady Macbeth)/DUNCAN/GENTLEWOMAN • SOLDIER/GILLACOMGAIN (first husband)/MACBETH’s SQUIRE/DOCTOR/MACDUFF • MACBETH • NURSE/BISHOP/SINT (can be played by a male or female) • CHORUS OF CROWS/GRUOCH’S ATTENDANTS/THE 3 WITCHES CHORUS will wear half-masks made to look like crows. There is nothing but interpretation. * * * * * Scene 1: First Lady Blackness. In the blackness, the sound of ELFRIDA, the queen, in carnal delight and distress—a rising wail halfway between pleasure and lamentation, with a final crescendo halfway between pleasure and a snarl. As this happens, a light up on young GRUOCH. When ELFRIDA is finished, a light up on ELFRIDA slipping on a simple rough cotton caftan. They sit apart, at some distance. They hold each other’s gaze, then GRUOCH looks away. ELFRIDA: Gruoch? We named you Gruoch—I don’t know why. I don’t think you can change it. The name sounds like it crawled out of the throats of crows. Would you like me to remember for you how your world began? Well? Not that you have many memories— GRUOCH: I heard—it—them—the screams—your screams—they—shook me—as I— SEVEN LADIES MACBETH • Page 1 GRUOCH makes a sliding motion with her hand: slipping out of the womb. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Macbeth Character Card Sort

Macbeth Character Card Sort SORT OUT THE CARDS INTO TWO PILES AND USE THE DESCRIPTIONS TO MATCH UP THE CHARACTER AND THE CORRECT NAME THE THREE WITCHES MACBETH LADY MACBETH BANQUO DONALBAIN MALCOLM LENNOX THE PORTER ROSS LADY MACDUFF MACDUFF DUNCAN FLEANCE © 2003 www.teachit.co.uk m237char Page 1 of 5 Macbeth Character Card Sort These characters add an element of Thane of Glamis and Cawdor, a general supernatural and prophecy to the play. in the King's army and husband he is a They each have a familiar, such as basically good man who is troubled by Graymalkin and Paddock, and are his conscience and loyalty though at the commanded by Hecate, a Greek goddess same time ambitious and murderous. He of the moon and witchcraft. They can is led to evil initially by the witches' use sieves as boats, and they can predictions and then by his wife's become an animal. They are described goading, which he gives into because he as having beards but looking human. loves her so. This woman is a good wife who loves her Thane of Lochaber, a general in the husband. She is also ambitious but lacks King's army. This man is the opposite the morals of her husband. To achieve of Macbeth, showing an alternate her ambition, she rids of herself of any reaction to prophecy. He keeps his kindness that might stand in the way. morals and allegiances, but ends up However, she runs out of energy to dying. He is brave and ambitious, but suppress her conscience and kills this is tempered by intelligence. -

From Real Time to Reel Time: the Films of John Schlesinger

From Real Time to Reel Time: The Films of John Schlesinger A study of the change from objective realism to subjective reality in British cinema in the 1960s By Desmond Michael Fleming Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 School of Culture and Communication Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Produced on Archival Quality Paper Declaration This is to certify that: (i) the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD, (ii) due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, (iii) the thesis is fewer than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. Abstract The 1960s was a period of change for the British cinema, as it was for so much else. The six feature films directed by John Schlesinger in that decade stand as an exemplar of what those changes were. They also demonstrate a fundamental change in the narrative form used by mainstream cinema. Through a close analysis of these films, A Kind of Loving, Billy Liar, Darling, Far From the Madding Crowd, Midnight Cowboy and Sunday Bloody Sunday, this thesis examines the changes as they took hold in mainstream cinema. In effect, the thesis establishes that the principal mode of narrative moved from one based on objective realism in the tradition of the documentary movement to one which took a subjective mode of narrative wherein the image on the screen, and the sounds attached, were not necessarily a record of the external world. The world of memory, the subjective world of the mind, became an integral part of the narrative. -

(Non-)Sense in King Lear by Carolin Roder

Wissenschaftliches Seminar Online Deutsche Shakespeare-Gesellschaft Ausgabe 5 (2007) Shakespearean Soundscapes: Music – Voices – Noises – Silence www.shakespeare-gesellschaft.de/publikationen/seminar/ausgabe2007 Wissenschaftliches Seminar Online 5 (2007) HERAUSGEBER Das Wissenschaftliche Seminar Online wird im Auftrag der Deutschen Shakespeare-Gesellschaft, Sitz Weimar, herausgegeben von: Dr. Susanne Rupp, Universität Hamburg, Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik, Von-Melle-Park 6, D-20146 Hamburg ([email protected]) Prof. Dr. Tobias Döring, Institut für Englische Philologie, Schellingstraße 3 RG, D-80799 München ([email protected]) Dr. Jens Mittelbach, Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen, Platz der Göttinger Sieben 1, 37073 Göttingen ([email protected]) ERSCHEINUNGSWEISE Das Wissenschaftliche Seminar Online erscheint im Jahresrhythmus nach den Shakespeare-Tagen der Deutschen Shakespeare-Gesellschaft und enthält Beiträge der Wissenschaftler, die das Wissenschaftli- che Seminar zum Tagungsthema bestreiten. HINWEISE FÜR BEITRÄGER Beiträge für das Wissenschaftliche Seminar Online sollten nach den Richtlinien unseres Stilblattes formatiert sein. Bitte laden sie sich das Stilblatt als PDF-Datei von unserer Webseite herunter: http://www.shakespeare-gesellschaft.de/uploads/media/stilblatt_manuskripte.pdf Bitte senden Sie Ihren Beitrag in einem gebräuchlichen Textverarbeitungsformat an einen der drei Herausgeber. INTERNATIONAL STANDARD SERIAL NUMBER ISSN 1612-8362 © Copyright 2008 Deutsche -

Macbeth in World Cinema: Selected Film and Tv Adaptations

International Journal of English and Literature (IJEL) ISSN 2249-6912 Vol. 3, Issue 1, Mar 2013, 179-188 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. MACBETH IN WORLD CINEMA: SELECTED FILM AND TV ADAPTATIONS RITU MOHAN 1 & MAHESH KUMAR ARORA 2 1Ph.D. Scholar, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India 2Associate Professor, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India ABSTRACT In the rich history of Shakespearean translation/transcreation/appropriation in world, Macbeth occupies an important place. Macbeth has found a long and productive life on Celluloid. The themes of this Bard’s play work in almost any genre, in any decade of any generation, and will continue to find their home on stage, in film, literature, and beyond. Macbeth can well be said to be one of Shakespeare’s most performed play and has enchanted theatre personalities and film makers. Much like other Shakespearean works, it holds within itself the most valuable quality of timelessness and volatility because of which the play can be reproduced in any regional background and also in any period of time. More than the localization of plot and character, it is in the cinematic visualization of Shakespeare’s imagery that a creative coalescence of the Shakespearean, along with the ‘local’ occurs. The present paper seeks to offer some notable (it is too difficult to document and discuss all) adaptations of Macbeth . The focus would be to provide introductory information- name of the film, country, language, year of release, the director, star-cast and the critical reception of the adaptation among audiences.