DISCLAIMER: This Document Does Not Meet the Current Format Guidelines of the Graduate S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IDO Dance Sports Rules and Regulations 2021

IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations 2021 Officially Declared For further information concerning Rules and Regulations contained in this book, contact the Technical Director listed in the IDO Web site. This book and any material within this book are protected by copyright law. Any unauthorized copying, distribution, modification or other use is prohibited without the express written consent of IDO. All rights reserved. ©2021 by IDO Foreword The IDO Presidium has completely revised the structure of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations. For better understanding, the Rules & Regulations have been subdivided into 6 Books addressing the following issues: Book 1 General Information, Membership Issues Book 2 Organization and Conduction of IDO Events Book 3 Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines Book 4 Code of Ethics / Disciplinary Rules Book 5 Financial Rules and Regulations Separate Book IDO Official´s Book IDO Dancers are advised that all Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines are now contained in Book 3 ("Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines"). IDO Adjudicators are advised that all "General Provisions for Adjudicators and Judging" and all rules for "Protocol and Judging Procedure" (previously: Book 5) are now contained in separate IDO Official´sBook. This is the official version of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations passed by the AGM and ADMs in December 2020. All rule changes after the AGM/ADMs 2020 are marked with the Implementation date in red. All text marked in green are text and content clarifications. All competitors are competing at their own risk! All competitors, team leaders, attendandts, parents, and/or other persons involved in any way with the competition, recognize that IDO will not take any responsibility for any damage, theft, injury or accident of any kind during the competition, in accordance with the IDO Dance Sport Rules. -

Introduction Writer Biographies for B&N Classics A. Michael Matin Is a Professor in the English Department of Warren Wilson

Introduction Writer Biographies for B&N Classics A. Michael Matin is a professor in the English Department of Warren Wilson College, where he teaches late-nineteenth-century and twentieth-century British and Anglophone postcolonial literature. His essays have appeared in Studies in the Novel, The Journal of Modern Literature, Scribners’ British Writers, Scribners’ World Poets, and the Norton Critical Edition of Kipling’s Kim. Matin wrote Introductions and Notes for Conrad’s Lord Jim and Heart of Darkness and Selected Short Fiction. Alfred Mac Adam, Professor at Barnard College–Columbia University, teaches Latin American and comparative literature. He is a translator of Latin American fiction and writes extensively on art. He has written an Introductions and Notes for H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine and The Invisible Man and The War of the Worlds, Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’ Les Liasons Dangereuses, and Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. Amanda Claybaugh is Associate Professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University. She is currently at work on a project that considers the relation between social reform and the literary marketplace in the nineteenth-century British and American novel. She has written an Introductions and Notes for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. Amy Billone is Assistant Professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville where her specialty is 19th Century British literature. She is the author of Little Songs: Women, Silence and the Nineteenth-Century Sonnet and has published articles on both children’s literature and poetry in numerous places. She wrote the Introduction and Notes for Peter Pan by J. -

Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Kevin Mercer University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Mercer, Kevin, "Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5540. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5540 HIPPIELAND: BOHEMIAN SPACE AND COUNTERCULTURAL PLACE IN SAN FRANCISCO’S HAIGHT-ASHBURY NEIGHBORHOOD by KEVIN MITCHELL MERCER B.A. University of Central Florida, 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the birth of the late 1960s counterculture in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Surveying the area through a lens of geographic place and space, this research will look at the historical factors that led to the rise of a counterculture here. To contextualize this development, it is necessary to examine the development of a cosmopolitan neighborhood after World War II that was multicultural and bohemian into something culturally unique. -

Riding at the Margins

Riding at the Margins International Media and the Construction of a Generic Outlaw Biker Identity in the South Island of New Zealand, circa 1950 – 1975. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Cultural Anthropology By David Haslett University of Canterbury Christchurch, New Zealand 2007 Abstract New Zealand has had a visible recreational motorcycle culture since the 1920s, although the forerunners of the later ‘outlaw’ motorcycle clubs really only started to emerge as loose-knit biker cliques in the 1950s. The first recognised New Zealand ‘outlaw club’, the Auckland chapter of the Californian Hell’s Angels M.C., was established on July 1961 (Veno 2003: 31). This was the Angels’ first international chapter, and only their fifth chapter overall at that time. Further outlaw clubs emerged throughout both the North and the South Island of New Zealand from the early 1960s, and were firmly established in both islands by the end of 1975. Outlaw clubs continue to flourish to this day. The basic question that motivated this thesis was how (the extent to which) international film, literature, media reports and photographic images (circa 1950 – 1975) have influenced the generic identity adopted by ‘outlaw’ motorcycle clubs in New Zealand, with particular reference to the South Island clubs. The focus of the research was on how a number of South Island New Zealand outlaw bikers interpreted international mass media representations of ‘outlaw’ biker culture between 1950 – 1975. This time span was carefully chosen after considerable research, consultation and reflection. It encompasses a period when New Zealand experienced rapid development of a global mass media, where cultural images were routinely communicated internationally in (relatively) real time. -

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Studies in Arts

Center for Open Access in Science Open Journal for Studies in Arts 2019 ● Volume 2 ● Number 2 https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojsa.0202 ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 OPEN JOURNAL FOR STUDIES IN ARTS (OJSA) ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 www.centerprode.com/ojsa.html [email protected] Publisher: Center for Open Access in Science (COAS) Belgrade, SERBIA www.centerprode.com [email protected] Editorial Board: Chavdar Popov (PhD) National Academy of Arts, Sofia, BULGARIA Vasileios Bouzas (PhD) University of Western Macedonia, Department of Applied and Visual Arts, Florina, GREECE Rostislava Todorova-Encheva (PhD) Konstantin Preslavski University of Shumen, Faculty of Pedagogy, BULGARIA Orestis Karavas (PhD) University of Peloponnese, School of Humanities and Cultural Studies, Kalamata, GREECE Meri Zornija (PhD) University of Zadar, Department of History of Art, CROATIA Responsible Editor: Goran Pešić Center for Open Access in Science, Belgrade Open Journal for Studies in Arts, 2019, 2(2), 35-70. ISSN ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 __________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS 35 From Figurative Painting to Painting of Substance – The Concept of an Artist Zdravka Vasileva 45 Spectacular Orientalism: Finding the Human in Puccini’s Turandot Francisca Folch-Couyoumdjian 57 Music and Environment: From Artistic Creation to the Environmental Sensitization and Action – A Circular Model Emmanouil C. Kyriazakos Open Journal for Studies in Arts, 2019, 2(2), 35-70. ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 __________________________________________________________________ -

Tabled Paper

ISSN 1322-0330 RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Hansard Home Page: http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/work-of-assembly/hansard Email: [email protected] Phone (07) 3553 6344 Fax (07) 3553 6369 FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-FIFTH PARLIAMENT Thursday, 10 November 2016 Subject Page PRIVILEGE ..........................................................................................................................................................................4455 Alleged Deliberate Misleading of the House by a Minister ............................................................................4455 Tabled paper: Extract from Record of Proceedings, dated 11 October 2016, of a speech during debate on the Domestic and Family Violence Protection and Other Legislation Amendment Bill. .....4455 PRIVILEGE ..........................................................................................................................................................................4455 Speaker’s Ruling, Alleged Deliberate Misleading of the House by a Minister ..............................................4455 Tabled paper: Correspondence from the member for Everton, Mr Tim Mander MP, and the Minister for Housing and Public Works, Hon. Mick de Brenni, to the Speaker, Hon. Peter Wellington, regarding an allegation of deliberately misleading the House. .......................................4455 Speaker’s Ruling, Alleged Deliberate Misleading of the House by a Minister ..............................................4456 Tabled paper: Correspondence from the member -

One Percent Motorcycle Clubs: Has the Media Constructed a Moral Panic in Kalgoorlie-Boulder, Western Australia? Dr Kira J Harris, Charles Sturt University

Charles Sturt University From the SelectedWorks of Dr Kira J Harris 2009 One Percent Motorcycle Clubs: Has the Media Constructed a Moral Panic in Kalgoorlie-Boulder, Western Australia? Dr Kira J Harris, Charles Sturt University Available at: https://works.bepress.com/kira_harris/20/ One Percent Motorcycle Clubs: Has the Media Constructed a Moral Panic in Kalgoorlie-Boulder, Western Australia? Kira Jade Harris BA(Psych), GradCertCrimnlgy&Just, GradDipCrimnlgy&Just, MCrimJus Faculty of Business and Law Edith Cowan University 2009 ii USE OF THESIS This copy is the property of Edith Cowan University. However, the literary rights of the author must also be respected. If any passage from this thesis is quoted or closely paraphrased in a paper or written work prepared by the user, the source of the passage must be acknowledged in the work. If the user desires to publish a paper or written work containing passages copied or closely paraphrased from this thesis, which passages would in total constitute an infringing copy for the purpose of the Copyright Act, he or she must first obtain the written permission of the author to do so. iii Abstract The purpose of this study was to evaluate an instrument designed to assess the influence of the media on opinions regarding the one percent motorcycle clubs in Kalgoorlie-Boulder, establishing whether the media had incited a moral panic towards the clubs. The concept of the moral panic, developed by Stanley Cohen (1972), is the widespread fear towards a social group by events that are overrepresented and exaggerated. Exploring the concept of a moral panic towards the one percent sub-culture, this study compares the perceptions from two groups of non-members in Kalgoorlie-Boulder. -

An Ethnographic Study of the Cultural World of Boy Racers by Zannagh Hatton Doctor of Philosophy May 2007

Tarmac Cowboys: an Ethnographic Study of the Cultural World of Boy Racers by Zannagh Hatton A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Law and Social Science, Faculty of Social Science and Business May 2007 90 0762650 0 REFBENCE USE OI\fLY University of Plymouth Library Item no. 9oo-7b9-fc>SoO ShelfrTiark ^, , , , Copyright Statement This copy of the thesis has been suppHed on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior consent. The Tarmac Cowboys: An Ethnographic Study of the Cultural World of Boy Racers By Zannagh Hatton Abstract Through my varying degrees of engagement with the street car culture which existed around the area where 1 lived in Comwall, 1 had become aware of the extent to which cars played an important role and represented the norm of daily discourse, entered into by others, and particularly young men. Yet as one of the dominant forms of mobility, the car appears to have been a neglected topic within sociology, cultural studies and related disciplines. Furthermore, 1 was unable to find a great deal of academic literature on the combined subjects of young men and motorcars, and in particular how consumption of the car and car related activities are used by some young men to express self-definition. This ethnographic study which has examined the cultural world of boy racers aged between 17 and 24 years is the result of my enquiry. -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

Captive Histories: English, French, and Native Narratives of the 1704 Deerfield Raid'

H-AmIndian Rine on Haefeli and Sweeney, 'Captive Histories: English, French, and Native Narratives of the 1704 Deerfield Raid' Review published on Monday, December 8, 2008 Evan Haefeli, Kevin Sweeney, eds. Captive Histories: English, French, and Native Narratives of the 1704 Deerfield Raid. Native Americans of the Northeast: Culture, History, and the Contemporary Series. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2006. xx + 298 pp. $22.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-55849-543-2. Reviewed by Holly A. Rine Published on H-AmIndian (December, 2008) Commissioned by Patrick G. Bottiger Other Voices Heard From: Uncovered Histories of 1704 Deerfield Raid In 1707, the first printing of Reverend John Williams’s narrative, The Redeemed Captive Returning to Zion, which recounts his captivity as a result of the 1704 raid on Deerfield, appeared for mass consumption. Since then it has taken its place alongside Mary Rowlandson’s 1682 account of her captivity during Metacom’s War, The Sovereignty and goodness of God, as one of the most famous and widely read colonial captivity narratives. Rowlandson’s and Williams’s accounts have provided centuries of readers with their understanding of the frontier experience in colonial New England, which primarily focused on the religious and political significance of the captivity experience, almost strictly from a puritan perspective. Moreover, Williams’s account has served as the inspiration and centerpiece of scholarly accounts of the 1704 raid as well as collections of captivity narratives.[1] Haefeli and Sweeney have been adding to our understanding of both the Williams narrative and the raid on Deerfield for over a decade. -

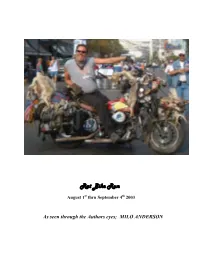

Day 2 We Met up with Hughy, a Friend of Randy and Carols from Washington in AM Before We Left Pendleton

Rat Bike Run st th August 1 thru September 4 2003 As seen through the Authors eyes; MILO ANDERSON Day1 August 1, 2003. I, Milo Anderson, my wife Joni Anderson, Randy and Carol Fergusen, Mitch and Jan Myers, Gino Benidetti, Bonnie Fender and Gordon Spezza left on our trip to Sturgis South Dakota. I was on my 1970 Shovelhead Rat Bike that I’ve been riding for 28 years. Joni was on her 2003 Heritage Soft Tail Classic. Randy was on his 2002 Soft Tail Deuce. Carol was on her 1999 Road King Classic. Gino and Bonnie were on his ’90 Springer. Mitch and Jan were on his ’95 Soft Tail and Gordon was driving the C & R Stripping truck and trailer with his 1978 Low Rider in back. We made it to Pendleton OR for the first day. It was also to be the day of the closest near tragedy of the whole trip. Joni, my wife, was going through a sweeping left hand corner with the river on the right side of the road. Her foot board bracket was scraping the asphalt in the middle of the turn. She looked down to see what was scrapping and when she looked up again she went straight off the road and into gravel. It was pretty scary for her, as well as for Mitch and Jan who were riding behind her. At approximately 40 MPH she had the back wheel try to slide out in the gravel and was sliding sideways. Joni remembers what we have told her in the past.