The Calamity Form :Onpoetry Andsocial Life EBSCO Publishing :Ebookcollection (Ebscohost)-Printed On3/30/20212:01 PM Viaunivofchicago !E Calamity Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IDO Dance Sports Rules and Regulations 2021

IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations 2021 Officially Declared For further information concerning Rules and Regulations contained in this book, contact the Technical Director listed in the IDO Web site. This book and any material within this book are protected by copyright law. Any unauthorized copying, distribution, modification or other use is prohibited without the express written consent of IDO. All rights reserved. ©2021 by IDO Foreword The IDO Presidium has completely revised the structure of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations. For better understanding, the Rules & Regulations have been subdivided into 6 Books addressing the following issues: Book 1 General Information, Membership Issues Book 2 Organization and Conduction of IDO Events Book 3 Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines Book 4 Code of Ethics / Disciplinary Rules Book 5 Financial Rules and Regulations Separate Book IDO Official´s Book IDO Dancers are advised that all Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines are now contained in Book 3 ("Rules for IDO Dance Disciplines"). IDO Adjudicators are advised that all "General Provisions for Adjudicators and Judging" and all rules for "Protocol and Judging Procedure" (previously: Book 5) are now contained in separate IDO Official´sBook. This is the official version of the IDO Dance Sport Rules & Regulations passed by the AGM and ADMs in December 2020. All rule changes after the AGM/ADMs 2020 are marked with the Implementation date in red. All text marked in green are text and content clarifications. All competitors are competing at their own risk! All competitors, team leaders, attendandts, parents, and/or other persons involved in any way with the competition, recognize that IDO will not take any responsibility for any damage, theft, injury or accident of any kind during the competition, in accordance with the IDO Dance Sport Rules. -

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

Scary Movies at the Cudahy Family Library

SCARY MOVIES AT THE CUDAHY FAMILY LIBRARY prepared by the staff of the adult services department August, 2004 updated August, 2010 AVP: Alien Vs. Predator - DVD Abandoned - DVD The Abominable Dr. Phibes - VHS, DVD The Addams Family - VHS, DVD Addams Family Values - VHS, DVD Alien Resurrection - VHS Alien 3 - VHS Alien vs. Predator. Requiem - DVD Altered States - VHS American Vampire - DVD An American werewolf in London - VHS, DVD An American Werewolf in Paris - VHS The Amityville Horror - DVD anacondas - DVD Angel Heart - DVD Anna’s Eve - DVD The Ape - DVD The Astronauts Wife - VHS, DVD Attack of the Giant Leeches - VHS, DVD Audrey Rose - VHS Beast from 20,000 Fathoms - DVD Beyond Evil - DVD The Birds - VHS, DVD The Black Cat - VHS Black River - VHS Black X-Mas - DVD Blade - VHS, DVD Blade 2 - VHS Blair Witch Project - VHS, DVD Bless the Child - DVD Blood Bath - DVD Blood Tide - DVD Boogeyman - DVD The Box - DVD Brainwaves - VHS Bram Stoker’s Dracula - VHS, DVD The Brotherhood - VHS Bug - DVD Cabin Fever - DVD Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh - VHS Cape Fear - VHS Carrie - VHS Cat People - VHS The Cell - VHS Children of the Corn - VHS Child’s Play 2 - DVD Child’s Play 3 - DVD Chillers - DVD Chilling Classics, 12 Disc set - DVD Christine - VHS Cloverfield - DVD Collector - DVD Coma - VHS, DVD The Craft - VHS, DVD The Crazies - DVD Crazy as Hell - DVD Creature from the Black Lagoon - VHS Creepshow - DVD Creepshow 3 - DVD The Crimson Rivers - VHS The Crow - DVD The Crow: City of Angels - DVD The Crow: Salvation - VHS Damien, Omen 2 - VHS -

Book-14 Web-Lmsx.Pdf

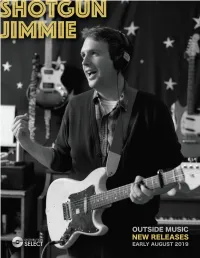

SHOTGUN JIMMIE – TRANSISTOR SISTER 2 LABEL: YOU’VE CHANGED RECORDS CATALOG: YC-039 FORMAT: LP/CD RELEASE DATE: AUGUST 2, 2019 Are you ready for the new sincerity?! Shotgun Jimmie’s new album Transistor Sister 2 is full of genuine pop gems that champion truth and love. Jimmie is joined by long- time collaborators Ryan Peters (Ladyhawk) and Jason Baird (DoMakeSayThink) for this sequel to the Polaris Prize nominated album Transistor Sister from 2011. José Contreras (By Divine Right) produced and recorded the record in Toronto, Ontario at The Chat Chateaux and joins the band on keys. In characteristic Shotgun Jimmie fashion, the songs on Transistor Sister 2 focus largely on family and friends with a heavy dose of nostalgia. Jimmie’s hyperbolic takes on the everyday reconstruct familiar scenarios, from traffic on the 401 (the beloved and scorned mega- highway through Toronto known to all touring musicians Blues Riffs as the place where punctual arrival at soundcheck goes Tumbleweed to die) to cooking dinner. Hot Pots Ablutions The album’s lead single Cool All the Time is a plea for Fountain people to abandon ego and strive for authenticity, Suddenly Submarine featuring contributions by Chad VanGaalen, Steven Piano (with band) Lambke and Cole Woods. The New Sincerity serves as The New Sincerity the album’s manifesto; it renounces cynicism and Cool All The Time promotes positivity. Sappy Slogans Highway 401 Jack Pine Sorry We’re Closed Shotgun Jimmie: IG: @shotgunjimmie FB: @shotgunjimmie Twitter: @jimmieshotgun You’ve Changed Records: www.youvechangedrecords.com CD – CD-YC-039 LP with download – LP-YC-039 Twitter: @youvechangedrec IG: @youvechangedrecords FB: @youvechangedrecords Also available from You’ve Changed Records: Partner – Saturday The 14th (YC-038) 12”EP/CD You’ve Changed Records Steven Lambke – Dark Blue (YC-037) LP 123 Pauline Ave. -

First Cut, the PILOT

THE FIRST CUT Written by Benjamin L. Hinnant PILOT WGA-w# 2004890 [email protected] FADE IN: EXT. WEST HOLLYWOOD, CALIFORNIA - NIGHT CU: AN OPEN EYE. Lifeless. Accentuated OFFSCREEN by RED & BLUE siren lights and red blood spatter. We are greeted by a LOUISIANA DRAWL: CAMILLE (V.O.) Around my way, the meaning of life is summed up in who comes to bury you, who gathers together in your name after you’ve gone, and how they remember and eulogize you. SLOW-MO: A bright red FORD FIESTA parks at the corner of the intersection. HE steps out the car, hood of his black hoodie covering his head. “TRAYVON MARTIN 1995-2012” on his back. TITLE CARD: “THE FIRST CUT” The trunk pops open. The hoodie comes off and is replaced with a “MEDICAL EXAMINER” windbreaker and cap. He grabs the PELICAN CASE, shuts the trunk, and locks the car by remote. CAMILLE GALLIEN is our boy-next-door handsome protagonist, thirty, a “Louisiana Creole” of color. He rounds the corner onto Havenhurst. The Andalusia building is cordoned off with “CRIME SCENE” tape. CRIME SCENE TECHS operate on auto-pilot. END SLOW-MO Waving Camille over wearing matching “Medical Examiner” gear is EZEKIAL FOGG, white, sixty, silver-haired. CAMILLE Dr. Fogg. You’re everywhere. FOGG Yeah, I’m what you call hands-on. Forget every episode of CSI you’ve ever committed to memory. Tonight’s a crash course on what you’ll learn during your year here. What is your first objective at the crime scene? CAMILLE To inventory as much information related to the body as I can. -

Studies in Arts

Center for Open Access in Science Open Journal for Studies in Arts 2019 ● Volume 2 ● Number 2 https://doi.org/10.32591/coas.ojsa.0202 ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 OPEN JOURNAL FOR STUDIES IN ARTS (OJSA) ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 www.centerprode.com/ojsa.html [email protected] Publisher: Center for Open Access in Science (COAS) Belgrade, SERBIA www.centerprode.com [email protected] Editorial Board: Chavdar Popov (PhD) National Academy of Arts, Sofia, BULGARIA Vasileios Bouzas (PhD) University of Western Macedonia, Department of Applied and Visual Arts, Florina, GREECE Rostislava Todorova-Encheva (PhD) Konstantin Preslavski University of Shumen, Faculty of Pedagogy, BULGARIA Orestis Karavas (PhD) University of Peloponnese, School of Humanities and Cultural Studies, Kalamata, GREECE Meri Zornija (PhD) University of Zadar, Department of History of Art, CROATIA Responsible Editor: Goran Pešić Center for Open Access in Science, Belgrade Open Journal for Studies in Arts, 2019, 2(2), 35-70. ISSN ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 __________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS 35 From Figurative Painting to Painting of Substance – The Concept of an Artist Zdravka Vasileva 45 Spectacular Orientalism: Finding the Human in Puccini’s Turandot Francisca Folch-Couyoumdjian 57 Music and Environment: From Artistic Creation to the Environmental Sensitization and Action – A Circular Model Emmanouil C. Kyriazakos Open Journal for Studies in Arts, 2019, 2(2), 35-70. ISSN (Online) 2620-0635 __________________________________________________________________ -

ELCOCK-DISSERTATION.Pdf

HIGH NEW YORK THE BIRTH OF A PSYCHEDELIC SUBCULTURE IN THE AMERICAN CITY A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By CHRIS ELCOCK Copyright Chris Elcock, October, 2015. All rights reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History Room 522, Arts Building 9 Campus Drive University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 Canada i ABSTRACT The consumption of LSD and similar psychedelic drugs in New York City led to a great deal of cultural innovations that formed a unique psychedelic subculture from the early 1960s onwards. -

Supernatural Aspect in James Wan's Movie the Conjuring Ii

SUPERNATURAL ASPECT IN JAMES WAN’S MOVIE THE CONJURING II A THESIS Submitted to the Adab and Humanities Faculty of Alauddin State Islamic University of Makassar in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Humanities Degree By: KURNIAWATI NIM. 40300112115 ENGLISH AND LITERATURE DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY ALAUDDIN STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY OF MAKASSAR 2018 1 2 3 4 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Alhamdulillahi rabbil „alamin, the researcher would like to express her confession and gratitude to the Most Perfection, Allah swt for the guidance, blessing and mercy in completing her thesis. Shalawat and salam are always be delivered to the big prophet Muhammad saw his family and followers till the end of the time. There were some problems faced by the researcher in accomplishing this research. Those problems could not be solved without any helps, motivations, criticisms and guidance from many people. Special thanks always addressed to the researcher’ beloved mother, Hj.Kasya and her beloved father, Alm. Alimuddin for all their prayers, supports and eternally affection as the biggest influence in her success and happy life. Thanks to her lovely brother Suharman S.Pd and thank to her lovely sister Karmawati, Amd. Keb for the happy and colorful life. The researcher’s gratitude goes to the Dean of Adab and Humanity Faculty, Dr. H. Barsihannor, M.Ag, to the head and secretary of English and Literature Department, H. Muh. Nur Akbar Rasyid, M.Pd., M.Ed., Ph.D and Syahruni Junaid, S.S., M.Pd for their suggestions, helps and supports administratively, all the lecturers of English and Literature Department and the administration staff of Adab and Humanity Faculty who have given numbers helps, guidance and very useful knowledge during the years of her study. -

Representations of Mental Illness, Queer Identity, and Abjection in High Tension

“I WON’T LET ANYONE COME BETWEEN US” REPRESENTATIONS OF MENTAL ILLNESS, QUEER IDENTITY, AND ABJECTION IN HIGH TENSION Krista Michelle Wise A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of May 2014 Committee: Becca Cragin, Advisor Marilyn Motz © 2014 Krista Wise All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Becca Cragin, Advisor In this thesis I analyze the presence of mental illness, queer identity and Kristeva’s theory of abjection in Alexandre Aja’s 2003 film High Tension. Specifically I look at the common trend within the horror genre of scapegoating those who are mentally ill or queer (or both) through High Tension. It is my belief that it is easier for directors, and society as a whole, to target marginalized groups (commonly referred to as the Other) as a means of expressing a “normalized” group’s anxiety in a safe and acceptable manner. High Tension allows audiences to reassure themselves of their sanity and, at the same time, experience hyper violence in a safe setting. Horror films have always targeted the fears of the dominant culture and I use this thesis to analyze the impact damaging perceptions may have on oppressed groups. iv “My mood swings have now turned my dreams into gruesome scenes” – Tech N9ne, “Am I a Psycho?” v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Becca Cragin and Dr. Marilyn Motz for their critique, suggestions, and feedback throughout this process. I consider myself very fortunate to have had their guidance, especially as a first generation MA student. -

Handsworth Songs and Touch of the Tarbrush 86

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/35838 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Voices of Inheritance: Aspects of British Film and Television in the 1980s and 1990s Ian Goode PhD Film and Television Studies University of Warwick Department of Film and Television Studies February 2000 · ~..' PAGE NUMBERING \. AS ORIGINAL 'r , --:--... ; " Contents Acknowledgements Abstract Introduction page 1 1. The Coupling of Heritage and British Cinema 10 2. Inheritance and Mortality: The Last of England and The Garden 28 3. Inheritance and Nostalgia: Distant Voices Still Lives and The Long Day Closes 61 4. Black British History and the Boundaries of Inheritance: Handsworth Songs and Touch of the Tarbrush 86 5. Exile and Modernism: London and Robinson in Space 119 6. Defending the Inheritance: Alan Bennett and the BBC 158 7. Negotiating the Lowryscape: Making Out, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit and Sex, Chips and Rock 'n' Roll 192 Conclusion 238 Footnotes 247 Bibliography 264 Filmography 279 .. , t • .1.' , \ '. < .... " 'tl . ',*,. ... ., ~ ..... ~ Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Charlotte Brunsdon for her patience, support and encouragement over the course of the thesis. I am also grateful to my parents for providing me with both space and comfortable conditions to work within and also for helping me to retain a sense of perspective. -

Best of '15 223 Songs, 14.6 Hours, 1.67 GB

Page 1 of 7 Best of '15 223 songs, 14.6 hours, 1.67 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Alligator 3:48 Carroll Carroll 2 Cinnamon 3:34 Dry Food Palehound 3 Say 4:02 Architect C Duncan 4 Leaf Off / The Cave 4:54 Vestiges & Claws José González 5 No Comprende 4:59 Ones and Sixes Low 6 Sweet Disaster 3:42 Leave No Bridge Unburned Whitehorse 7 Highway Patrol Stun Gun 4:10 Savage Hills Ballroom Youth Lagoon 8 Hey Lover 3:23 Break Mirrors Blake Mills 9 Pretty Pimpin 4:59 b'lieve i'm goin down... Kurt Vile 10 Courage 4:47 Darling Arithmetic Villagers 11 The Knock 3:33 Painted Shut Hop Along 12 Random Name Generator 3:50 Star Wars Wilco 13 Lonesome Street 4:23 The Magic Whip Blur 14 Midway 3:05 Psychic Reader Bad Bad Hats 15 Mountain At My Gates 4:04 What Went Down Foals 16 False Hope 3:12 Short Movie Laura Marling 17 The Ground Walks, with Time in a… 6:10 Strangers to Ourselves [Explicit] Modest Mouse 18 Elevator Operator 3:15 Sometimes I Sit and Think, And S… Courtney Barnett 19 The Night Josh Tillman Came To… 3:36 I Love You, Honeybear Father John Misty 20 Bollywood 6:19 Love Songs For Robots Patrick Watson 21 Ghosts 3:31 Ibeyi Ibeyi 22 No No No 2:51 No No No Beirut 23 This Dark Desire 3:14 The Most Important Place in the… Bill Wells 24 My Terracotta Heart 4:05 The Magic Whip Blur 25 Billions of Eyes 5:10 After Lady Lamb 26 Early Morning Riser 2:50 Sirens The Weepies 27 Bread and Butter 4:00 Rhythm & Reason Bhi Bhiman 28 No One Can Tell 3:52 Savage Hills Ballroom Youth Lagoon 29 The Less I Know The Better [Expli… 3:36 Currents [Explicit] Tame Impala -

Sensational Soul Cruisers Song List the Tramps

Sensational Soul Cruisers Song List The Tramps - Disco Inferno - Hold Back The Night KC and the Sunshine Band - Sound Your Funky Horn - Get Down Tonight - I‛m Your Boogie Man - Shake Your Booty - That‛s The Way I Like It - Baby Give It Up - Please Don‛t Go The Moments - Love On A Two Way Street The Bee Gees - You Should Be Dancin - Night Fever Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes - The Love I Lost - If You Don‛t Know Me By Now - Bad Luck - I Don‛t Love You Anymore The O‛Jays - Love Train - I Love Music - Back Stabbers - Used To Be My Girl The ChiLites - Have You Seen Her - Oh Girl Gladys Knight - The Best Thing That Ever Happened To Me - Midnight Train To Georgia Earth, Wind & Fire - September - Sing a Song - Shining Star - Let‛s Groove Main Ingredient - Everybody Plays The Fool Johnny Nash - I Can See Clearly Now Isley Brothers - Work To Do - It‛s Your Thing - Shout - Twist & Shout Tavares - It Only Takes a Minute - Free Ride - Heaven Must Be Missing an Angel - Don‛t Take Away The Music The Foundations - Now That I‛ve Found You Barry White - Can‛t Get Enough of You Babe - You‛re My First My Last My Everything - What Am I Gonna Do - Ecstasy (When You Lay Down Next To Me) Edwin Starr - 25 Miles The Platters - Only You Soul Survivors - Expressway Billy Ocean - Are You Ready George Benson - Turn Your Love Around Billy Ocean - Are You Ready Heat Wave - Boogie Nights - Always and Forever - Groove Line Bell & James - Livin It Up (Friday Night) Peter Brown - Dance With Me Jigsaw - Skyhigh Tyrone Davis - Turn Back the Hands of Time The Stylistics -