Metal Machine Music: Technology, Noise, and Modernism in Industrial Music 1975-1996

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Industrial-Tinged Pop That Has More Than a Few Hints of Legendary Metal

::WHAT PEOPLE ARE SAYING. “Industrial-tinged pop that has more than a few hints of legendary metal-adjacent bands Depeche Mode and Nine Inch Nails. Plus they still work in the noise blasts of their earlier material, and what metalhead doesn’t like a little noise?” - BrookynVegan / Invisible Oranges (2016’s #1 Non-Metal Band Metalheads Should Be Listening To) “HEALTH has actually made a very loud pop album, one that is turned up to daring extremes.” - The New Yorker "A band turning heavy rock, club music and edgy pop inside-out.” - LA Times “A monstrous album on which its electronic and industrial mystique has matured to represent an absorption of the band’s discography, injected with a serum of growth hormones.” - Onion A/V Club (A-) ::RECENT MUSIC -/ HEALTH remix of Ghost’s “He Is” (click to listen) -/ HEALTH soundtrack cover of New Order’s Blue Monday for Atomic Blonde film (click to listen) ::RECENT HIGHLIGHTS AND BREAKS -/ On tour with The Neighborhood (Spring / Summer 2018) -/ Adult Swim “Single Series” for (click to listen) -/ Triple J (AUS) fully supporting album, “STONEFIST” added and one of their most played records of 2015 -/ STONEFIST single named Pitchfork BEST NEW TRACK -/ Sundance Next Festival film premiere with the legendary Pablo Ferro ::RADIO HIGHLIGHTS -/ Sirius XMU premiered “NEW COKE”, peaked 30+ spins per week -/ BBC Radio 1 Dan P Carter premiered and supported “STONEFIST” -/ #4 most added on CMJ, peaked #8 on CJM 200 -/ KEXP session and XMU takeover week of release ::PRESS AND TV HIGHLIGHTS -/ Features in The New Yorker, NPR “First Listen”, Billboard, LA Times (Arts cover), LA Weekly, Pitchfork, FADER, Noisey, Stereogum, DIY, FACT, and more -/ Glowing reviews from The Onion A/V Club (A-), Best of Line Fit (9/10), Alternative Press (4/5), NME (4/5), and more. -

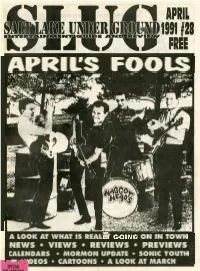

April's Fools

APRIL'S FOOLS ' A LOOK AT WHAT IS REAL f ( i ON IN. TOWN NEWS VIEWS . REVIEWS PREVIEWS CALENDARS MORMON UPDATE SONIC YOUTH -"'DEOS CARTOONS A LOOK AT MARCH frlday, april5 $7 NOMEANSNO, vlcnms FAMILYI POWERSLAVI saturday, april 6 $5 an 1 1 piece ska bcnd from cdlfomb SPECKS witb SWlM HERSCHEL SWIM & sunday,aprll7 $5 from washln on d.c. m JAWBO%, THE STENCH wednesday, aprl10 KRWTOR, BLITZPEER, MMGOTH tMets $10raunch, hemmetal shoD I SUNDAY. APRIL 7 I INgTtD, REALITY, S- saturday. aprll $5 -1 - from bs aqdes, califomla HARUM SCAIUM, MAG&EADS,;~ monday. aprlll5 free 4-8. MAtERldl ISSUE, IDAHO SYNDROME wedn apri 17 $5 DO^ MEAN MAYBE, SPOT fiday. am 19 $4 STILL UFEI ALCOHOL DEATH saturday, april20 $4 SHADOWPLAY gooah TBA mday, 26 Ih. rlrdwuhr tour from a land N~AWDEATH, ~O~LESH;NOCTURNUS tickets $10 heavy metal shop, raunch MATERIAL ISSUE I -PRIL 15 I comina in mayP8 TFL, TREE PEOPLE, SLaM SUZANNE, ALL, UFT INSANE WARLOCK PINCHERS, MORE MONDAY, APRIL 29 I DEAR DICKHEADS k My fellow Americans, though:~eopledo jump around and just as innowtiwe, do your thing let and CLIJG ~~t of a to NW slam like they're at a punk show. otherf do theirs, you sounded almost as ENTEIWAINMENT man for hispoeitivereviewof SWIM Unfortunately in Utah, people seem kd as L.L. "Cwl Guy" Smith. If you. GUIIBE ANIB HERSCHELSWIMsdebutecassette. to think that if the music is fast, you are that serious, I imagine we will see I'mnotamemberofthebancljustan have to slam, but we're doing our you and your clan at The Specks on IMVIEW avid ska fan, and it's nice to know best to teach the kids to skank cor- Sahcr+nightgiwingskrmkin'Jessom. -

In Search of Silence Kindle

IN SEARCH OF SILENCE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK POORNA BELL | 272 pages | 02 May 2019 | Simon & Schuster Ltd | 9781471169212 | English | London, United Kingdom In Search of Silence PDF Book Traveling across the country and meeting and listening to a host of incredible characters, including doctors, neuroscientists, acoustical engineers, monks, activists, educators, marketers, and aggrieved citizens, George Prochnik examines why we began to be so loud as a society, and what it is that gets lost when we can no longer find quiet. The book was also rather puffy around the middle and it felt like we were going over and over again about the same points. Your First Name. More filters. Frank Allen and Tina Chunna Zhang. Sort order. Signed up for the Goodreads Reading Challenge and looking for tips on how to discover and read more books? The producers selected to create work have been announced and the CBAA's third annual National Features and Documentary Series is shaping up as a must-listen in late Error rating book. Single and video use the video edit of the song. Digital release [6]. Want to Read saving…. About In Pursuit of Silence A brilliant, far-reaching exploration of the frontiers of noise and silence, and the growing war between them. I feel that she could have explored the topic at a much deeper level. The colorful descriptors draw you into her experience, inviting you to observe and participate in her emotions and journey to forgiveness through unimaginable grief and loneliness. In Search of Silence is the recognition of the echo chamber we find ourselves in, in terms of what constitutes a successful, fulfilling life. -

Moment Sound Vol. 1 (MS001 12" Compilation)

MOMENT SOUND 75 Stewart Ave #424, Brooklyn NY, 11237 momentsound.com | 847.436.5585 | [email protected] Moment Sound Vol. 1 (MS001 12" Compilation) a1 - Anything (Slava) a2 - Genie (Garo) a3 - Violence Jack (Lokua) a4 - Steamship (Garo) b1 - Chiberia (Lokua) b2 - Nightlife Reconsidered (Garo) b3 - Cosmic River (Slava) Scheduled for release on March 9th, 2010 The Moment Sound Vol. 1 compilation is the inauguration of the vinyl series of the Moment Sound label. It is comprised of original material by its founders Garo, Lokua and Slava. Swirling analog synths, dark pensive moods and intricate drum programming fill out the LP and at times evoke references to vintage Chicago house, 80's horror-synth, British dub and early electro. A soft, dreamlike atmosphere coupled with an understated intensity serves as the unifying character of the compilation. ….... Moment Sound is a multi-faceted label overseen by three musicians from Chicago – Joshua Kleckner, Garo Tokat and Slava Balasanov. All three share a fascination with and desire to uncover the essence of music – its primal building blocks. Minute details of old and new songs of various genres are sliced and dissected, their rhythmic and melodic elements carefully analyzed and cataloged to be recombined into a new, unpredictable yet classic sound. Performing live electronics together since early 2000s – anywhere from art galleries to grimy warehouse raves and various traditional music venues – they have proven to be an undeniable and highly versatile force in the Chicago music scene. Moment Sound does not have a static "sound". Instead, the focus is on the aesthetic of innovation rooted in tradition – a meeting point of the past and the future – the sound of the moment. -

2011-11-25 1. När Det Är Spelning På Nuclear Nation Brukar Det Komma

Nuclear Nation Quiz - 2011-11-25 1. När det är spelning på Nuclear Nation brukar det komma mycket folk. Det gör det ibland även annars och då kan det bli långa köer som ringlar sig runt Linköping. Under tidigt 2000-tal kunde NN- besökare vid ett festtillfälle slippa kötristeseen och gå direkt in på festen förutsatt att de uppfyllde ett krav. Vad skulle två NN-besökare göra för att få gå före i kön? A: Bära likadana kläder B: Kunna texten till Headhunter utantill och sjunga den tvåstämmigt C: Vara fastkedjade i varandra 2. Ni befinner er just nu på synthquiz med den anrika synthföreningen Nuclear Nation, men det var inte helt självklart att vi skulle heta just så. Vilket annat namn fanns som förslag? A: Eclipse B: Solaris C: SUN 3. Apoptygma Berzerk gjorde 98 en spelning i Leipzig från vilken i alla fall en liten del kom med på skivan APBL98. Trots att bandet körde på som hårdast med en Depeche-cover som folk verkade uppskatta, så fick spelningen ett snöpligt slut. Men vad hände? A: Det utbröt en mindre en brand i ljudteknikerbåset pga. underdimensionerade elkablar. B: Spelningen råkade äga rum samma kväll som kraftverket Holzkohle fallerade, vilket ledde till Leipzigs hittills största elavbrott. C: Trots att Apoptygma ville köra en låt till, så stängde polisen ner konserten i förtid. 4. En inställd spelning är också en spelning brukar man säga och ett band som skulle ha spelat på NN för ett antal år sedan, men som tyvärr fick ställa in p.g.a. sjukdom var... ja, vilket band då? A: Covenant B: VNV Nation C: Tyskarna från Lund 5: Ett band som dock har spelat på NN är LOWE. -

Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository August 2016 Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E. Morley The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Keir Keightley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts © Briana E. Morley 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Morley, Briana E., "Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3991. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3991 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Abstract There is a dark mythology surrounding the post-punk band Joy Division that tends to foreground the personal history of lead singer Ian Curtis. However, when evaluating the construction of Joy Division’s public image, the contributions of several other important figures must be addressed. This thesis shifts focus onto the peripheral figures who played key roles in the construction and perpetuation of Joy Division’s image. The roles of graphic designer Peter Saville, of television presenter and Factory Records founder Tony Wilson, and of photographers Kevin Cummins and Anton Corbijn will stand as examples in this discussion of cultural intermediaries and collaborators in popular music. -

Reed First Pages

4. Northern England 1. Progress in Hell Northern England was both the center of the European industrial revolution and the birthplace of industrial music. From the early nineteenth century, coal and steel works fueled the economies of cities like Manchester and She!eld and shaped their culture and urban aesthetics. By 1970, the region’s continuous mandate of progress had paved roads and erected buildings that told 150 years of industrial history in their ugly, collisive urban planning—ever new growth amidst the expanding junkyard of old progress. In the BBC documentary Synth Britannia, the narrator declares that “Victorian slums had been torn down and replaced by ultramodern concrete highrises,” but the images on the screen show more brick ruins than clean futurescapes, ceaselessly "ashing dystopian sky- lines of colorless smoke.1 Chris Watson of the She!eld band Cabaret Voltaire recalls in the late 1960s “being taken on school trips round the steelworks . just seeing it as a vision of hell, you know, never ever wanting to do that.”2 #is outdated hell smoldered in spite of the city’s supposed growth and improve- ment; a$er all, She!eld had signi%cantly enlarged its administrative territory in 1967, and a year later the M1 motorway opened easy passage to London 170 miles south, and wasn’t that progress? Institutional modernization neither erased northern England’s nineteenth- century combination of working-class pride and disenfranchisement nor of- fered many genuinely new possibilities within culture and labor, the Open Uni- versity notwithstanding. In literature and the arts, it was a long-acknowledged truism that any municipal attempt at utopia would result in totalitarianism. -

Design Project: Big Beat DJ Project Overview

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Department of Electrical, Computer, and Systems Engineering ECSE 4560: Signal Processing Design, Spring 2003 Professor: Richard Radke, JEC 7006, 276-6483 Design Project: Big Beat DJ “I never worked a day in my life; I just laid back and let the big beat lead me.” - The Jungle Brothers Project Overview A good techno DJ spins a continuous stream of music by seamlessly mixing one song into the next. This involves not only synchronizing the beats of the songs to be mixed, but also incrementally adjusting the pitches of the songs so that during the transition, neither song sounds unnatural. Your goal in this project is to use signal processing to produce a computerized DJ that can automatically produce a non-stop mix of music given a library of non-synchronized tracks as input. On top of this basic specification, additional points will be given for implementing advanced techniques like sampling, beat juggling and airbeats that make the mix more exciting. At the end of the term, the computer DJs will face off in a Battle for World Supremacy with a library of entirely novel songs. Basic Deliverables To meet the basic design requirement, your group should deliver • An m-file named bpm.m with syntax b = bpm(song) where song is the name of a music .wav file (or the vector of music samples themselves), and b is the estimated number of beats per minute in the specified song. • An m-file named songmix.m with syntax mix = = songmix(song1,song2), where mix is the resultant continuous mix between song1 and song2. -

Throbbing Gristle 40Th Anniv Rough Trade East

! THROBBING GRISTLE ROUGH TRADE EAST EVENT – 1 NOV CHRIS CARTER MODULAR PERFORMANCE, PLUS Q&A AND SIGNING 40th ANNIVERSARY OF THE DEBUT ALBUM THE SECOND ANNUAL REPORT Throbbing Gristle have announced a Rough Trade East event on Wednesday 1 November which will see Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti in conversation, and Chris Carter performing an improvised modular set. The set will be performed predominately on prototypes of a brand new collaboration with Tiptop Audio. Chris Carter has been working with Tiptop Audio on the forthcoming Tiptop Audio TG-ONE Eurorack module, which includes two exclusive cards of Throbbing Gristle samples. Chris Carter has curated the sounds from his personal sonic archive that spans some 40 years. Card one consists of 128 percussive sounds and audio snippets with a second card of 128 longer samples, pads and loops. The sounds have been reworked and revised, modified and mangled by Carter to give the user a unique Throbbing Gristle sounding palette to work wonders with. In addition to the TG themed front panel graphics, the module features customised code developed in collaboration with Chris Carter. In addition, there will be a Throbbing Gristle 40th Anniversary Q&A event at the Rough Trade Shop in New York with Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, date to be announced. The Rough Trade Event coincides with the first in a series of reissues on Mute, set to start on the 40th anniversary of their debut album release, The Second Annual Report. On 3 November 2017 The Second Annual Report, presented as a limited edition white vinyl release in the original packaging and also on double CD, and 20 Jazz Funk Greats, on green vinyl and double CD, will be released, along with, The Taste Of TG: A Beginner’s Guide to Throbbing Gristle with an updated track listing that will include ‘Almost A Kiss’ (from 2007’s Part Two: Endless Not). -

A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2011 No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson Jr. Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Horace E. Anderson, Jr., No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us, 20 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 115 (2011), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/818/. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. No Bitin' Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson, Jr: I. History and Purpose of Copyright Act's Regulation of Copying ..................................................................................... 119 II. Impact of Technology ................................................................... 126 A. The Act of Copying and Attitudes Toward Copying ........... 126 B. Suggestions from the Literature for Bridging the Gap ......... 127 III. Potential Influence of Norms-Based Approaches to Regulation of Copying ................................................................. 129 IV. The Hip-Hop Imitation Paradigm ............................................... -

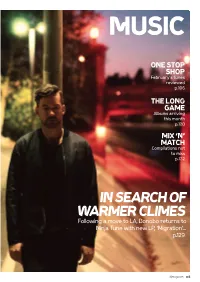

IN SEARCH of WARMER CLIMES Following a Move to LA, Bonobo Returns to Ninja Tune with New LP, ‘Migration’

MUSIC ONE STOP SHOP February’s tunes reviewed p.106 THE LONG GAME Albums arriving this month p.128 MIX ‘N’ MATCH Compilations not to miss p.132 IN SEARCH OF WARMER CLIMES Following a move to LA, Bonobo returns to Ninja Tune with new LP, ‘Migration’... p.129 djmag.com 105 HOUSE BEN ARNOLD QUICKIES Roberto Clementi Avesys EP [email protected] Pets Recordings 8.0 Sheer class from Roberto Clementi on Pets. The title track is brooding and brilliant, thick with drama, while 'Landing A Man'’s relentless thump betrays a soft and gentle side. Lovely. Jagwar Ma Give Me A Reason (Michael Mayer Does The Amoeba Remix) Marathon MONEY 8.0 SHOT! Showing that he remains the master (and managing Baba Stiltz to do so in under seven minutes too), Michael Mayer Is Everything smashes this remix of baggy dance-pop dudes Studio Barnhus Jagwar Ma out of the park. 9.5 The unnecessarily young Baba Satori Stiltz (he's 22) is producing Imani's Dress intricate, brilliantly odd house Crosstown Rebels music that bearded weirdos 8.0 twice his age would give their all chopped hardcore loops, and a brilliance from Tact Recordings Crosstown is throwing weight behind the rather mid-life crises for. Think the bouncing bassline. Sublime work. comes courtesy of roadman (the unique sound of Satori this year — there's an album dizzying brilliance of Robag small 'r' is intentional), aka coming — but ignore the understatedly epic Ewan Whrume for a reference point, Dorsia Richard Fletcher. He's also Tact's Pearson mixes of 'Imani's Dress' at your peril. -

By Dardo I Editor

By Dardo Editor: Unleashed2k April 2019 CUSTOMSFORGE’S MONTHLY NEWSLETTER Issue #6 WELCOME ABOUT US Welcome to CustomsForge’s monthly newsletter, where you can find the CustomsForge is a website latest news about CF and Rocksmith 2014 Remastered. created in 2014 by the April fools Rocksmith community to make their own songs, Surprise! Were you expecting another serious list with an intricate article about the origins and characteristics of a musical genre? Well, this might be communicate more easily and different but it’s as good as any of those things. After all, everyone likes enjoy the game all together humour and when you mix it with some great songs and some tight musicianship, you get this amazing cocktail of musical talent and funny Currently we are approaching lyrics. more than 35,000 charts made by the community, and Parody/Joke songs have more than 250,000 “Weird Al” Yankovic – Eat It members. “Weird Al” Yankovic – CNR “Weird Al” Yankovic – Amish Paradise We welcome thousands more Beatallica – I Want to Choke Your Band each month The Lonely Island – Dick in a Box ft. Justin Timberlake Alexander Pushnoy – Porushka Paranya The Rutles – I Must Be In Love Steel Panther – Sex and Candy Steel Panther – The Ballad of Mona Lisa Steel Panther – Supersonic Sex Machine Red Plesen – Gitler Yugend Rock N Roll Flight of the Conchords – Business Time Flight of the Conchords – Hiphopopotamus vs. Rhymenoceros Cannabis Corpse – Chronolith Tenacious D – The Metal Tenacious D – Tribute Tenacious D - Beelzeboss Spinal Tap – Gimme Some Money Spinal Tap – Big Bottom Spinal Tap – Sex Farm Rocksmith 2014 Remastered logo By Dardo Editor: Unleashed2k April 2019 “ I wanted a site and project I could call my own, something I could step back and say: “wow, I did this, I made this happen”, and CustomsForge became exactly that.” “Mark with YouTuber FreddieW at MAGFest 2019” someone who loves both gaming and guitar, it sparked my interest.