Reed First Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The ABC of Sheffield Music Nostalgia - SLIDESHOW - the Star Page 1 of 2

The ABC of Sheffield music nostalgia - SLIDESHOW - The Star Page 1 of 2 The ABC of Sheffield music nostalgia - SLIDESHOW Video See all the bands in our slideshow Just like old times: Heaven 17’s Glenn Gregory and Martyn Ware, top right ABC’s Martin Fry and, above, Phil Oakey « Previous « Previous Next » Next » ADVERTISEMENT Published Date: 15 December 2008 By John Quinn A MAJOR pop music event took place on Saturday night. But let's ignore The X Factor. Several thousand Sheffielders did, instead opting for a night of not-just-nostalgia with three of the best-known acts ever to hail from around here – The Human League, ABC and Heaven 17. Whatever entertainment Simon Cowell's crew provides, one negative effect is spoiling the suspense and potential surprise of the race for the Christmas number one single. However the crowd at an impressively almost-full Arena preferred to hark back to the days when the festive chart-topper could be made by a weird synthesizer group whose singer had responded to a split in the ranks by recruiting two teenage girls with no musical talent except the ability to dance and sing. Well, sort of... The city's music scene at that time consisted largely of electronic experimentalists, some of whom suddenly discovered they could write pop songs. Very good pop songs at that, which sold by the bucketload until the tide of fashion changed. The acts still exist, albeit after several line-up changes each, and occasionally release albums to diminishing returns, so whoever decided to combine all three pulled off a masterstroke. -

Philip's Electronic Pioneers Still in a League of Their

Thursday, December 4, 2014 www.yorkshireeveningpost.co.uk Yorkshire evening Post 33 EMAIL WEB [email protected] yorkshireeveningpost.co.uk features l 33 info&adviCe +++ Twitter:@ LeedsNews +++ Philip’s electronic pioneers duty chemists Fri, 8am to 8pm; Sat and Sun, to find out duty chemists in 8am to 2pm). your area ring the following teenage pregnancy and numbers between 9am-5pm: parenthood helpline: Open West Yorkshire Central Mon to Fri , 9.30am to 5pm. services: 0113 2952 500. 24-hour answer phone all other Calderdale and kirklees: times. 0808 808 4444. 01484 466 009. Leeds Life Pregnancy Centre still in a league of their own north Yorkshire: 01904 Counselling and Advice: 825 110. Oxford Place Chambers, Oxford “We didn’t want to be after you’ve had a few hits, the out of hours or for other Place LS1 3AX. 0755 400 3000. areas: NHS 111 at any time. Leeds Contraception and Celebrity beaten, that was the big thing. name doesn’t matter.” sexual health service: Leeds At every stage, people would Like most eighties artists, EMERGENCY 0113 295 3359 (office hours). Other times call NHS Direct 08 interview turn around and say, ‘These oakey is still very proud of the gas: Freephone 0800 111999. electricity: Freephone 0800 45 46 47 for details of clinics. James Nuttall people are actually talentless, visual impact his band had. 375675. Leeds Mediation service: MUSIC WRITER and they’re going to be gone in “All that fashion stuff was Water: Yorkshire Water, 0845 Difficulties with neighbours? zzEmail: [email protected] 1242424. -

Moment Sound Vol. 1 (MS001 12" Compilation)

MOMENT SOUND 75 Stewart Ave #424, Brooklyn NY, 11237 momentsound.com | 847.436.5585 | [email protected] Moment Sound Vol. 1 (MS001 12" Compilation) a1 - Anything (Slava) a2 - Genie (Garo) a3 - Violence Jack (Lokua) a4 - Steamship (Garo) b1 - Chiberia (Lokua) b2 - Nightlife Reconsidered (Garo) b3 - Cosmic River (Slava) Scheduled for release on March 9th, 2010 The Moment Sound Vol. 1 compilation is the inauguration of the vinyl series of the Moment Sound label. It is comprised of original material by its founders Garo, Lokua and Slava. Swirling analog synths, dark pensive moods and intricate drum programming fill out the LP and at times evoke references to vintage Chicago house, 80's horror-synth, British dub and early electro. A soft, dreamlike atmosphere coupled with an understated intensity serves as the unifying character of the compilation. ….... Moment Sound is a multi-faceted label overseen by three musicians from Chicago – Joshua Kleckner, Garo Tokat and Slava Balasanov. All three share a fascination with and desire to uncover the essence of music – its primal building blocks. Minute details of old and new songs of various genres are sliced and dissected, their rhythmic and melodic elements carefully analyzed and cataloged to be recombined into a new, unpredictable yet classic sound. Performing live electronics together since early 2000s – anywhere from art galleries to grimy warehouse raves and various traditional music venues – they have proven to be an undeniable and highly versatile force in the Chicago music scene. Moment Sound does not have a static "sound". Instead, the focus is on the aesthetic of innovation rooted in tradition – a meeting point of the past and the future – the sound of the moment. -

Skinny Puppy Bites Mp3, Flac, Wma

Skinny Puppy Bites mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Bites Country: Benelux Released: 1989 Style: EBM, Industrial MP3 version RAR size: 1200 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1709 mb WMA version RAR size: 1932 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 248 Other Formats: DMF ADX MP3 MP2 APE TTA AC3 Tracklist Hide Credits Attack Assimilate A1 6:56 Mixed By, Tape, Synthesizer [Bass], Effects [Treaments], Sampler – Tom Ellard The Choke A2 6:25 Synthesizer [Bass] – Wilhelm Schroeder Blood On The Wall A3 2:51 Bass – Mr D Pleven* A4 Church 3:12 Decay Deadlines B1 6:15 Guitar – Cevin Key B2 Last Call 5:52 B3 Basement 3:15 B4 Tomorrow 4:57 Companies, etc. Published By – Nettwerk Overboard Publ. Published By – Les Editions Confidentielles Recorded At – Mushroom Studios, Vancouver Recorded At – Doghouse Studios Pressed By – Sony/CBS, Haarlem – 08-024787-20 Printed By – Sony/CBS, Haarlem – 08-024787-20 Mastered At – Foon Credits Engineer – Cevin Key, David Ogilvie* Executive Producer – Terry McBride Producer – Cevin Key (tracks: A2 to A4, B1 to B4), David Ogilvie* (tracks: A2 to A4, B1 to B4), Tom Ellard (tracks: A1) Sleeve – Steven • R • Gilmore* Sleeve [Assistant] – Greg Sykes Synthesizer, Sequenced By, Tape, Sampler, Effects [Treatments], Percussion, Drums, Programmed By [Rhythm], Bass – Cevin Key Voice, Lyrics By, Synthesizer, Percussion, Effects [Treatments], Other [Objects] – Nivek Ogre Written-By, Performer – Skinny Puppy Notes Recorded 1984 - 1985 at Mushroom Studios, except tracks A4 & B4 which are recorded on 4track in the Dog House. -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Shakespearean Actors Display Talents at ND

II III II 11111111111i'" Program Guide Specialty Shows 7 - 9 pm Daily ., Monday: Regressive Thursday: Hlp Hop WI! aRJ Tuesday: Rock-n-Roll/Sports Friday: Reggae Request Line: . Wednesday: Jazz Saturday: Hardcore/ 239-6400 ==============64 Sunday: Metal Punk These are the Voices of the Fighting Irish Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Mike BertinI Jason Hoida Mike Schwabe Pat Ninneman John Strieder Kathy Hordlek 7-9 a.m. "Rock Out With "Morning 'We're Brellking "H Hint Of 'Hot Brellkfllst Your Rooster Out" Stiffness" Pllrietllls' Hnesthesia" In No Time Rt RII" ~ ~ John Staunton Mystery D,J, Kristen Moria SullilJan Kelly Boglarsky ~/ffff/h • Sol & Cllrol's 'If I Rsked You To Baumler 'Mllnioclll "Bogue Not V#//ffM 9-11a.m. Spllnk Me, Would You Mudslinging BBO Plulldlse" Say N01 "Un Poco De Sko" Menllqerie' Uogue" 10:00 am - 1 :00 pm Paul Broderick John Dugan Greg Murphy Joson Wins lode Mike Montroy Rebecca Paul Saiz 'Jazun Jetsam's 11-lp.m. "Paul's Power "Nothing Short of "Midday "Bloodshot OSCillating Rudlo "Death By Ciletti Hour (or two)" Total War" Cramps" Karma" Sculpture' Disco" Chris Chris Infante Brad Barnhorst Karen 1-3p.m. Neil Higgins Kristen John Furey Scherzinger "Big Cheese "No LOlJe Lost" Holderer 'Rlldio Schlep Goes Downer" Harknett "Undergromd" Public' Dan langrill Jeff Sepeta Jeff Jotz Mike McMahon Shllwn Nowlerskl Jennifer Hnne Seifert 3-5 p.m. 'Don Lllngrill's "Uoices On The "Orifice Party "Me Rnd Your 'Songs O'Bjorn Rnd "ElJeryday Is Rudio Mood Ring' Fringe" '90" Mom" Fjords' Reiland Like Sundaq" Mark KelJin Brian Geraghty Kathy RleH Nunez Hlyson Naimoli Tom Fellrath "The Urban MCDonou~h • Eluls HilS Left 5-7 p.m. -

The Educative Experience of Punk Learners

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 6-1-2014 "Punk Has Always Been My School": The Educative Experience of Punk Learners Rebekah A. Cordova University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Recommended Citation Cordova, Rebekah A., ""Punk Has Always Been My School": The Educative Experience of Punk Learners" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 142. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/142 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. “Punk Has Always Been My School”: The Educative Experience of Punk Learners __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Morgridge College of Education University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Rebekah A. Cordova June 2014 Advisor: Dr. Bruce Uhrmacher i ©Copyright by Rebekah A. Cordova 2014 All Rights Reserved ii Author: Rebekah A. Cordova Title: “Punk has always been my school”: The educative experience of punk learners Advisor: Dr. Bruce Uhrmacher Degree Date: June 2014 ABSTRACT Punk music, ideology, and community have been a piece of United States culture since the early-1970s. Although varied scholarship on Punk exists in a variety of disciplines, the educative aspect of Punk engagement, specifically the Do-It-Yourself (DIY) ethos, has yet to be fully explored by the Education discipline. -

Throbbing Gristle 40Th Anniv Rough Trade East

! THROBBING GRISTLE ROUGH TRADE EAST EVENT – 1 NOV CHRIS CARTER MODULAR PERFORMANCE, PLUS Q&A AND SIGNING 40th ANNIVERSARY OF THE DEBUT ALBUM THE SECOND ANNUAL REPORT Throbbing Gristle have announced a Rough Trade East event on Wednesday 1 November which will see Chris Carter and Cosey Fanni Tutti in conversation, and Chris Carter performing an improvised modular set. The set will be performed predominately on prototypes of a brand new collaboration with Tiptop Audio. Chris Carter has been working with Tiptop Audio on the forthcoming Tiptop Audio TG-ONE Eurorack module, which includes two exclusive cards of Throbbing Gristle samples. Chris Carter has curated the sounds from his personal sonic archive that spans some 40 years. Card one consists of 128 percussive sounds and audio snippets with a second card of 128 longer samples, pads and loops. The sounds have been reworked and revised, modified and mangled by Carter to give the user a unique Throbbing Gristle sounding palette to work wonders with. In addition to the TG themed front panel graphics, the module features customised code developed in collaboration with Chris Carter. In addition, there will be a Throbbing Gristle 40th Anniversary Q&A event at the Rough Trade Shop in New York with Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, date to be announced. The Rough Trade Event coincides with the first in a series of reissues on Mute, set to start on the 40th anniversary of their debut album release, The Second Annual Report. On 3 November 2017 The Second Annual Report, presented as a limited edition white vinyl release in the original packaging and also on double CD, and 20 Jazz Funk Greats, on green vinyl and double CD, will be released, along with, The Taste Of TG: A Beginner’s Guide to Throbbing Gristle with an updated track listing that will include ‘Almost A Kiss’ (from 2007’s Part Two: Endless Not). -

From Surrealism to Now

WHAT WE CALL LOVE FROM SURREALISM TO NOW IMMA, Dublin catalogue under the direction of Christine Macel and Rachael Thomas [Cover] Wolfgang Tillmans, Central Nervous System, 2013, inkjet print on paper mounted on aluminium in artist’s frame, frame: 97 × 82 cm, edition of 3 + 1 AP Andy Warhol, Kiss, 1964, 16mm print, black and white, silent, approx. 54 min at 16 frames per second © 2015 THE ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM, PITTSBURG, PA, COURTESY MAUREEN PALEY, LONDON. © WOLFGANG TILLMANS A MUSEUM OF CARNEGIE INSTITUTE. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. FILM STILL COURTESY OF THE ANDY WARHOL MUSEUM. PHOTO © CENTRE POMPIDOU, MNAM-CCI, DIST. RMN-GRAND PALAIS / GEORGES MEGUERDITCHIAN CONTENTS E 1 FOREWORD Sarah Glennie 6 WHAT WE CALL LOVE Christine Macel 13 SURREALISM AND L’AMOUR FOU FROM ANDRÉ BRETON TO HENRIK OLESEN / FROM THE 1920s TO NOW 18 ANDRÉ BRETON AND MAD LOVE George Sebbag 39 CONCEPTUAL ART / PERFORMANCE ART FROM YOKO ONO TO ELMGREEN AND DRAGSET / FROM THE 1960s TO NOW 63 NEW COUPLES FROM LOUISE BOURGEOIS TO JIM HODGES / FROM THE 1980s TO NOW 64 AGAINST DESIRE: A MANIFESTO FOR CHARLES BOVARY? Eva Illouz 84 THE NEUROBIOLOGY OF LOVE Semir Zeki 96 LOVE ACTION Rachael Thomas WHAT 100 LIST OF WORKS 104 BIBLIOGRAPHY WE CALL LOVE CHAPTER TITLE F FOREWORD SARAH GLENNIE, DIRECTOR The Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) is pleased to present this publication, which accompanies the large scale group exhibition, What We Call Love: From Surrealism to Now. This exhibition was initially proposed by Christine Macel (Chief Curator, Centre Pompidou), who has thoughtfully curated the exhibition alongside IMMA’s Rachael Thomas (Senior Curator: Head of Exhibitions). -

Survival Research Laboratories: a Dystopian Industrial Performance Art

arts Article Survival Research Laboratories: A Dystopian Industrial Performance Art Nicolas Ballet ED441 Histoire de l’art, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Galerie Colbert, 2 rue Vivienne, 75002 Paris, France; [email protected] Received: 27 November 2018; Accepted: 8 January 2019; Published: 29 January 2019 Abstract: This paper examines the leading role played by the American mechanical performance group Survival Research Laboratories (SRL) within the field of machine art during the late 1970s and early 1980s, and as organized under the headings of (a) destruction/survival; (b) the cyborg as a symbol of human/machine interpenetration; and (c) biomechanical sexuality. As a manifestation of the era’s “industrial” culture, moreover, the work of SRL artists Mark Pauline and Eric Werner was often conceived in collaboration with industrial musicians like Monte Cazazza and Graeme Revell, and all of whom shared a common interest in the same influences. One such influence was the novel Crash by English author J. G. Ballard, and which in turn revealed the ultimate direction in which all of these artists sensed society to be heading: towards a world in which sex itself has fallen under the mechanical demiurge. Keywords: biomechanical sexuality; contemporary art; destruction art; industrial music; industrial culture; J. G. Ballard; machine art; mechanical performance; Survival Research Laboratories; SRL 1. Introduction If the apparent excesses of Dada have now been recognized as a life-affirming response to the horrors of the First World War, it should never be forgotten that society of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s was laboring under another ominous shadow, and one that was profoundly technological in nature: the threat of nuclear annihilation. -

Media Release Tune Into Nature Music Prize Winner

Media Release Tune Into Nature Music Prize Winner LYDIAH selected as recipient of the inaugural Tune Into Nature Music Prize Yorkshire Sculpture Park is delighted to announce the winner of the Tune Into Nature Music Prize, originated by Professor Miles Richardson from the Nature Connectedness Research Group at the University of Derby and supported by Selfridges, Tileyard London and YSP. The winner LYDIAH says: “Becoming the winner of the Tune Into Nature Music Prize has been such a blessing, I’m so grateful to have been given the opportunity. It’s definitely going to help me progress as an artist. Having Selfridges play my track in store and to be associated with such an incredible movement for Project Earth is something that I am very proud of and excited for. I’m able to use the funding to support my debut EP, which couldn’t have come at a better time! The Prize is such a great project and the message is so important. I can’t thank Miles, Martyn and everyone who supports it enough.” Twenty-one year old LYDIAH, based in Liverpool, has been selected as the winner of the Tune Into Nature Music Prize for her entry I Eden. The composition is written from the point of view of Mother Nature and highlights the dangers of humans becoming increasingly distanced from the natural world. LYDIAH will receive a £1,000 grant to support her work, the opportunity to perform at Timber Festival in 2021 and a remix with Tileyard London produced by Principal Martyn Ware (Heaven 17), who says: “I thoroughly enjoyed helping to judge some exceptional entries for this unique competition. -

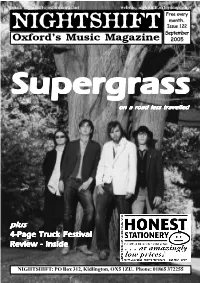

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 122 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SupergrassSupergrassSupergrass on a road less travelled plus 4-Page Truck Festival Review - inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE YOUNG KNIVES won You Now’, ‘Water and Wine’ and themselves a coveted slot at V ‘Gravity Flow’. In addition, the CD Festival last month after being comes with a bonus DVD which picked by Channel 4 and Virgin features a documentary following Mobile from over 1,000 new bands Mark over the past two years as he to open the festival on the Channel recorded the album, plus alternative 4 stage, alongside The Chemical versions of some tracks. Brothers, Doves, Kaiser Chiefs and The Magic Numbers. Their set was THE DOWNLOAD appears to have then broadcast by Channel 4. been given an indefinite extended Meanwhile, the band are currently in run by the BBC. The local music the studio with producer Andy Gill, show, which is broadcast on BBC recording their new single, ‘The Radio Oxford 95.2fm every Saturday THE MAGIC NUMBERS return to Oxford in November, leading an Decision’, due for release on from 6-7pm, has had a rolling impressive list of big name acts coming to town in the next few months. Transgressive in November. The monthly extension running through After their triumphant Truck Festival headline set last month, The Magic th Knives have also signed a publishing the summer, and with the positive Numbers (pictured) play at Brookes University on Tuesday 11 October.