My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Billboard.Com “Finesse” Hits a New High After Cardi B Hopped on the Track’S Remix, Which Arrived on Jan

GRAMMYS 2018 ‘You don’t get to un-have this moment’ LORDE on a historic Grammys race, her album of the year nod and the #MeToo movement PLUS Rapsody’s underground takeover and critics’ predictions for the Big Four categories January 20, 2018 | billboard.com “Finesse” hits a new high after Cardi B hopped on the track’s remix, which arrived on Jan. 4. COURTESY OF ATLANTIC RECORDS ATLANTIC OF COURTESY Bruno Mars And Cardi B Title CERTIFICATION Artist osition 2 Weeks Ago Peak P ‘Finesse’ Last Week This Week PRODUCER (SONGWRITER) IMPRINT/PROMOTION LABEL Weeks On Chart #1 111 6 WK S Perfect 2 Ed Sheeran 120 Their Way Up W.HICKS,E.SHEERAN (E.C.SHEERAN) ATLANTIC sic, sales data as compiled by Nielsen Music and streaming activity data by online music sources tracked by Nielsen Music. tracked sic, activity data by online music sources sales data as compiled by Nielsen Music and streaming Havana 2 Camila Cabello Feat. Young Thug the first time. See Charts Legend on billboard.com/biz for complete rules and explanations. © 2018, Prometheus Global Media, LLC and Nielsen Music, Inc. Global Media, LLC All rights reserved. © 2018, Prometheus for complete rules and explanations. the first time. See Charts on billboard.com/biz Legend 3 2 2 222 FRANK DUKES (K.C.CABELLO,J.L.WILLIAMS,A.FEENY,B.T.HAZZARD,A.TAMPOSI, The Hot 100 B.LEE,A.WOTMAN,P.L.WILLIAMS,L.BELL,R.L.AYALA RODRIGUEZ,K.GUNESBERK) SYCO/EPIC DG AG SG Finesse Bruno Mars & Cardi B - 35 3 32 RUNO MARS AND CARDI B achieve the career-opening feat, SHAMPOO PRESS & CURL,STEREOTYPES (BRUNO MARS,P.M.LAWRENCE II, C.B.BROWN,J.E.FAUNTLEROY II,J.YIP,R.ROMULUS,J.REEVES,R.C.MCCULLOUGH II) ATLANTIC bring new jack swing and the second male; Lionel Richie back to the top 10 of the landed at least three from each of his 2 3 4 Rockstar 2 Post Malone Feat. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

Most Underrated Band of All Time?

:: View email as a web page :: For the past 15 years, Manchester Orchestra has been one of the most popular emo bands on the planet. The one person who has been there every step of the way is founding singer-songwriter Andy Hull, who started the band when he was in his teens and has charted his own growing-up process with each album. Manchester Orchestra has also matured a lot over the years, evolving from an intense and volatile post-hardcore outt on albums like 2009’s Mean Everything To Nothing to the expansive and philosophical indie rock of their latest, The Million Masks Of God, which drops next week. Along the way, they’ve managed to somehow grow their audience while retaining committed fans who connected with the early records as teenagers, including famous acolytes like Phoebe Bridgers and Julien Baker. “Even though everything did well at that time, it wasn’t really accepted by critics and ‘cool’ people,” Hull recently mused about his back catalogue, “and that totally worked in our favor, because it still holds up. It sounds, to me, pretty timeless.” Ahead of the release of The Million Masks Of God, Hull reected on every Manchester Orchestra LP, candidly breaking down the myriad fascinating dramas that marked the process of making each record. Check it out here. -- Steven Hyden, Uproxx Cultural Critic and author of This Isn't Happening: Radiohead's "Kid A" and the Beginning of the 21st Century In case you missed it... The latest Indiecast visualizer digs further into the ongoing conict between Morrissey and The Simpsons. -

'Boxing Clever

NOVEMBER 05 2018 sandboxMUSIC MARKETING FOR THE DIGITAL ERA ISSUE 215 ’BOXING CLEVER SANDBOX SUMMIT SPECIAL ISSUE Event photography: Vitalij Sidorovic Music Ally would like to thank all of the Sandbox Summit sponsors in association with Official lanyard sponsor Support sponsor Networking/drinks provided by #MarketMusicBetter ast Wednesday (31st October), Music Ally held our latest Sandbox Summit conference in London. While we were Ltweeting from the event, you may have wondered why we hadn’t published any reports from the sessions on our site and ’BOXING CLEVER in our bulletin. Why not? Because we were trying something different: Music Ally’s Sandbox Summit conference in London, IN preparing our writeups for this special-edition sandbox report. From the YouTube Music keynote to panels about manager/ ASSOCIATION WITH LINKFIRE, explored music marketing label relations, new technology and in-house ad-buying, taking in Fortnite and esports, Ed Sheeran, Snapchat campaigns and topics, as well as some related areas, with a lineup marketing to older fans along the way, we’ve broken down the key views, stats and debates from our one-day event. We hope drawn from the sharp end of these trends. you enjoy the results. :) 6 | sandbox | ISSUE 215 | 05.11.2018 TALES OF THE ’TUBE Community tabs, premieres and curation channels cited as key tools for artists on YouTube in 2018 ensions between YouTube and the music industry remain at raised Tlevels following the recent European Parliament vote to approve Article 13 of the proposed new Copyright Directive, with YouTube’s CEO Susan Wojcicki and (the day after Sandbox Summit) music chief Lyor Cohen both publicly criticising the legislation. -

WEB KARAOKE EN-NL.Xlsx

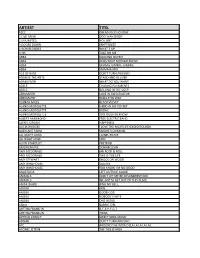

ARTIEST TITEL 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 2 LIVE CREW DOO WAH DIDDY 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP A HA TAKE ON ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMMIE GIMMIE GIMMIE ABBA MAMMA MIA ACE OF BASE DON´T TURN AROUND ADAM & THE ANTS STAND AND DELIVER ADAM FAITH WHAT DO YOU WANT ADELE CHASING PAVEMENTS ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY ALANAH MILES BLACK VELVET ALANIS MORISSETTE HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALBERT HAMMOND FREE ELECTRIC BAND ALEXIS JORDAN HAPPINESS ALICIA BRIDGES I LOVE THE NIGHTLIFE (DISCO ROUND) ALIEN ANT FARM SMOOTH CRIMINAL ALL NIGHT LONG LIONEL RICHIE ALL RIGHT NOW FREE ALVIN STARDUST PRETEND AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN AMY MCDONALD MR ROCK & ROLL AMY MCDONALD THIS IS THE LIFE AMY STEWART KNOCK ON WOOD AMY WINEHOUSE VALERIE AMY WINEHOUSE YOU KNOW I´M NO GOOD ANASTACIA LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANIMALS DON´T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD ANIMALS WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS PLACE ANITA WARD RING MY BELL ANOUK GIRL ANOUK GOOD GOD ANOUK NOBODY´S WIFE ANOUK ONE WORD AQUA BARBIE GIRL ARETHA FRANKLIN R-E-S-P-E-C-T ARETHA FRANKLIN THINK ARTHUR CONLEY SWEET SOUL MUSIC ASWAD DON´T TURN AROUND ATC AROUND THE WORLD (LA LA LA LA LA) ATOMIC KITTEN THE TIDE IS HIGH ARTIEST TITEL ATOMIC KITTEN WHOLE AGAIN AVRIL LAVIGNE COMPLICATED AVRIL LAVIGNE SK8TER BOY B B KING & ERIC CLAPTON RIDING WITH THE KING B-52´S LOVE SHACK BACCARA YES SIR I CAN BOOGIE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE YOU AIN´T SEEN NOTHING YET BACKSTREET BOYS -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Reed First Pages

4. Northern England 1. Progress in Hell Northern England was both the center of the European industrial revolution and the birthplace of industrial music. From the early nineteenth century, coal and steel works fueled the economies of cities like Manchester and She!eld and shaped their culture and urban aesthetics. By 1970, the region’s continuous mandate of progress had paved roads and erected buildings that told 150 years of industrial history in their ugly, collisive urban planning—ever new growth amidst the expanding junkyard of old progress. In the BBC documentary Synth Britannia, the narrator declares that “Victorian slums had been torn down and replaced by ultramodern concrete highrises,” but the images on the screen show more brick ruins than clean futurescapes, ceaselessly "ashing dystopian sky- lines of colorless smoke.1 Chris Watson of the She!eld band Cabaret Voltaire recalls in the late 1960s “being taken on school trips round the steelworks . just seeing it as a vision of hell, you know, never ever wanting to do that.”2 #is outdated hell smoldered in spite of the city’s supposed growth and improve- ment; a$er all, She!eld had signi%cantly enlarged its administrative territory in 1967, and a year later the M1 motorway opened easy passage to London 170 miles south, and wasn’t that progress? Institutional modernization neither erased northern England’s nineteenth- century combination of working-class pride and disenfranchisement nor of- fered many genuinely new possibilities within culture and labor, the Open Uni- versity notwithstanding. In literature and the arts, it was a long-acknowledged truism that any municipal attempt at utopia would result in totalitarianism. -

Love Ain't Got No Color?

Sayaka Osanami Törngren LOVE AIN'T GOT NO COLOR? – Attitude toward interracial marriage in Sweden Föreliggande doktorsavhandling har producerats inom ramen för forskning och forskarutbildning vid REMESO, Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärdsstudier, Linköpings universitet. Samtidigt är den en produkt av forskningen vid IMER/MIM, Malmö högskola och det nära samarbetet mellan REMESO och IMER/MIM. Den publiceras i Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. Vid filosofiska fakulteten vid Linköpings universitet bedrivs forskning och ges forskarutbildning med utgångspunkt från breda problemområden. Forskningen är organiserad i mångvetenskapliga forskningsmiljöer och forskarutbildningen huvudsakligen i forskarskolor. Denna doktorsavhand- ling kommer från REMESO vid Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärdsstudier, Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 533, 2011. Vid IMER, Internationell Migration och Etniska Relationer, vid Malmö högskola bedrivs flervetenskaplig forskning utifrån ett antal breda huvudtema inom äm- nesområdet. IMER ger tillsammans med MIM, Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, ut avhandlingsserien Malmö Studies in International Migration and Ethnic Relations. Denna avhandling är No 10 i avhandlingsserien. Distribueras av: REMESO, Institutionen för Samhälls- och Välfärsstudier, ISV Linköpings universitet, Norrköping SE-60174 Norrköping Sweden Internationell Migration och Etniska Relationer, IMER och Malmö Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare, MIM Malmö Högskola SE-205 06 Malmö, Sweden ISSN -

The Educative Experience of Punk Learners

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 6-1-2014 "Punk Has Always Been My School": The Educative Experience of Punk Learners Rebekah A. Cordova University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Recommended Citation Cordova, Rebekah A., ""Punk Has Always Been My School": The Educative Experience of Punk Learners" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 142. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/142 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. “Punk Has Always Been My School”: The Educative Experience of Punk Learners __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Morgridge College of Education University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Rebekah A. Cordova June 2014 Advisor: Dr. Bruce Uhrmacher i ©Copyright by Rebekah A. Cordova 2014 All Rights Reserved ii Author: Rebekah A. Cordova Title: “Punk has always been my school”: The educative experience of punk learners Advisor: Dr. Bruce Uhrmacher Degree Date: June 2014 ABSTRACT Punk music, ideology, and community have been a piece of United States culture since the early-1970s. Although varied scholarship on Punk exists in a variety of disciplines, the educative aspect of Punk engagement, specifically the Do-It-Yourself (DIY) ethos, has yet to be fully explored by the Education discipline. -

Swervedriver Mezcal Head Mp3, Flac, Wma

Swervedriver Mezcal Head mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Mezcal Head Country: UK Released: 1993 Style: Alternative Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1143 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1354 mb WMA version RAR size: 1571 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 771 Other Formats: AIFF VQF DMF ASF VOC AU DXD Tracklist 1 For Seeking Heat 3:46 2 Duel 5:51 3 Blowin' Cool 3:57 4 MM Abduction 2:51 5 Last Train To Satansville 6:45 6 Harry & Maggie 5:27 7 A Change Is Gonna Come 3:59 8 Girl On A Motorbike 4:09 9 Duress 8:03 10 You Find It Everywhere 4:10 Credits Engineer – Jez , Nick Addison Producer, Engineer – Alan Moulder Written-By – Marc Waterman (tracks: 9), Swervedriver Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 5017556601433 Other versions Title Category Artist Label Category Country Year (Format) 31454 0129 4, Mezcal Head A&M Records, 31454 0129 4, Swervedriver Canada 1993 314540129-4 (Cass, Album) A&M Records 314540129-4 Second Motion LP-SMR-007, Mezcal Head LP-SMR-007, Swervedriver Records, Hi- US 2011 HSS-1032-1 (LP, RE, TP) HSS-1032-1 Speed Soul Mezcal Head 31454 0129 2 Swervedriver A&M Records 31454 0129 2 Canada 1993 (CD, Album) Second Motion LP-SMR-007, Mezcal Head LP-SMR-007, Swervedriver Records, Hi- US 2011 HSS-1032-1 (LP, Num, RE) HSS-1032-1 Speed Soul Second Motion SMR-007, Mezcal Head Records, Hi- SMR-007, HSS-1032, Swervedriver (CD, Album, Speed Soul, HSS-1032, US 2009 B0012422-02 RE, RM) Universal Music B0012422-02 Special Markets Comments about Mezcal Head - Swervedriver IGOT Probably goes without say, but f**k this album is amazing and never gets old! If for some reason you've been living under a rock for the last 25 years, get your head in the game and listen to this masterpiece! So damn good! Thank you Adam and Co. -

BIMM Birmingham City and Accommodation Guide 2021/22

Birmingham City and Accommodation Guide 2021/22 bimm.ac.uk Contents Welcome Welcome 3 As Principal of BIMM Institute Birmingham, I’m hugely excited to be at the helm of our newest UK college, About Birmingham 4 located at the heart of this vibrant creative and artistic My Birmingham 10 musical city. About BIMM Institute Birmingham 12 At BIMM Institute, we give you an experience of the real BIMM Institute Birmingham Lecturers 16 industry as it stands today – it’s our mission to create BIMM Institute Birmingham Courses 18 a microcosm of the music business within the walls of Location 22 the college. If you’re a songwriter, you’ll find the best musicians to collaborate with; if you’re a guitarist, bassist, Your City 24 drummer or vocalist, you’ll find the best songwriters and Music Resources 28 fellow band members. If you’re a Music Business, Music Production, Event Management or Music Marketing, Media Accommodation Guide 34 and Communication student, you’ll have access to the best Join Us in Birmingham 38 emerging musical talent the city has to offer. BIMM Institute is a hotbed of talent and being a BIMM student means you’ll be part of that community, making many vital connections, which you’ll hopefully keep for the rest of your life and career. The day you walk into BIMM Institute as a freshly enrolled student is the first day of your career. While you’re a BIMM student, you’ll be immersed in the industry. You’ll be taught by current music professionals who bring real, up-to-date experience directly into the classroom, and the curriculum they’re teaching is current and relevant because it constantly evolves with the latest developments in the business.