From Surrealism to Now

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philip's Electronic Pioneers Still in a League of Their

Thursday, December 4, 2014 www.yorkshireeveningpost.co.uk Yorkshire evening Post 33 EMAIL WEB [email protected] yorkshireeveningpost.co.uk features l 33 info&adviCe +++ Twitter:@ LeedsNews +++ Philip’s electronic pioneers duty chemists Fri, 8am to 8pm; Sat and Sun, to find out duty chemists in 8am to 2pm). your area ring the following teenage pregnancy and numbers between 9am-5pm: parenthood helpline: Open West Yorkshire Central Mon to Fri , 9.30am to 5pm. services: 0113 2952 500. 24-hour answer phone all other Calderdale and kirklees: times. 0808 808 4444. 01484 466 009. Leeds Life Pregnancy Centre still in a league of their own north Yorkshire: 01904 Counselling and Advice: 825 110. Oxford Place Chambers, Oxford “We didn’t want to be after you’ve had a few hits, the out of hours or for other Place LS1 3AX. 0755 400 3000. areas: NHS 111 at any time. Leeds Contraception and Celebrity beaten, that was the big thing. name doesn’t matter.” sexual health service: Leeds At every stage, people would Like most eighties artists, EMERGENCY 0113 295 3359 (office hours). Other times call NHS Direct 08 interview turn around and say, ‘These oakey is still very proud of the gas: Freephone 0800 111999. electricity: Freephone 0800 45 46 47 for details of clinics. James Nuttall people are actually talentless, visual impact his band had. 375675. Leeds Mediation service: MUSIC WRITER and they’re going to be gone in “All that fashion stuff was Water: Yorkshire Water, 0845 Difficulties with neighbours? zzEmail: [email protected] 1242424. -

The American Poetry Review

“As soon as we subscribe to a hierarchy, we circumscribe ourselves within a value system. This is perhaps the great conundrum AMERICAN of art—once we define a term, we impose a limit, thereby inviting both orthodoxy and transgression. Our concept of ‘art’ or ‘poem’ or ‘novel’ is, then, always in flux, and I think we’d agree that this is how art renews itself—through those who dare to challenge those terms. The making of art, and the evaluation of it, is always an act POETRY REVIEW of self-definition.” —KITANO, p. 37 MAY/JUNE 2021 VOL. 50/NO. 3 $5 US/$7 CA MEGAN FERNANDES MAGICAL REALISM IN AMERICA & OTHER POEMS FORREST GANDER OWNING YOURSELF: AN INTERVIEW WITH JACK GILBERT SALLY WEN MAO PARIS SYNDROME & OTHER POEMS ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: ALISON C. ROLLINS MAGGIE SMITH NATALIE EILBERT PHOTO: APRWEB.ORG RIVKAH GEVINSON 2 THE AMERICAN POETRY REVIEW The American Poetry Review (issn 0360-3709) is published bimonthly by World Poetry, Inc., a non-profit corporation, and Old City Publishing, Inc. Edi torial offices: 1906 Rittenhouse Square, Philadelphia, PA 19103-5735. Subscription rates: U.S.: 3 years, $78.00; 2 years, $56.00; 1 year, $32.00. Foreign rates: 3 years, $129.00; 2 years, $92.00; 1 year, $49.00. Single copy, $5.00. Special classroom adoption rate per year per student: MAY/JUNE 2021 VOL. 50/NO. 3 $14.00. Free teacher’s subscription with classroom adoption. Subscription mail should be addressed to The American IN THIS ISSUE Poetry Review, c/o Old City Publishing, 628 N. -

Full Program (Pdf)

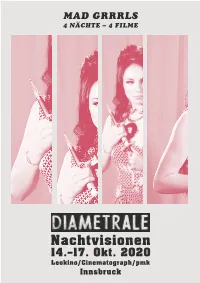

MAD GRRRLS 4 NÄCHTE – 4 FILME Nachtvisionen 14.–17. Okt. 2020 Leokino/Cinematograph/pmk Innsbruck 2. DIAMETRALE Nachtvisionen 14. – 17. Oktober 2020 im Leokino/Cinematograph/p.m.k MAD GRRRLS – transgressiv, transaggressiv, transfantastisch! Die Nachtvisionen beleben die Tradition der Spätvorstellungen in Innsbruck wieder – und bringen damit die dazugehörenden Genrefilme ins Leokino! Ob Klassiker oder moderne Produktionen, die nächtlichen Visionen widmen sich transgressiven Nischen- kategorien: B-Movies, Undergroundfilme, Exploitation-, Trash-, Genrekino... Kurz gesagt alles, was damals noch mit einem X versehen war, heute in der Kultfilmlade schlummert und nur darauf wartet, euch nächtens zu berauschen. Das diesjährige Programm der Nachtvisionen nimmt starke, selbst- bewusste Frauen in den Fokus. Unter dem Motto MAD GRRRLS wird Frauen- und Freiheitskampf verhandelt, feministischer Lust- mord und fetischisierte Rachlust thematisiert und Hedonismus und weibliche Selbstbestimmtheit gefeiert. Die Zusammenstellung von 2 Klassikern und 2 Neuproduktionen, jeweils von 2 Regisseurinnen und von 2 Regisseuren, ermöglicht nicht nur interessante, filmge- schichtliche Vergleiche, sondern befeuert die vielfältige Imagination von starken Frauen. Wir wünschen schrillfeministische und transfantastische Kinonächte! Verein zur Förderung experimenteller und komischer FilmKunst 3 Informationen Tickets Einzeltickets Kino 9,50 EUR ermäßigt 7,90 EUR*) *) Studierende und alle unter 25. Do 15.10. p.m.k 7,00 EUR –Einzeltickets für die Filme sind an der Kasse im Leokino und Cinematograph erhältlich. –Tickets für die Veranstaltung in der p.m.k sind nur an der Abendkasse erhältlich. COVID-19 Alle Veranstaltungen finden unter Berück- sichtigung der geltenden COVID-19-Verord- nung statt. Infos: www.diametrale.at/tickets Reservierung Leokino/Cinematograph Tel. +43 512 560470/-50 oder ein charmantes Mail an [email protected] Karten müssen 15 Minuten vor den Screenings abgeholt werden. -

Reed First Pages

4. Northern England 1. Progress in Hell Northern England was both the center of the European industrial revolution and the birthplace of industrial music. From the early nineteenth century, coal and steel works fueled the economies of cities like Manchester and She!eld and shaped their culture and urban aesthetics. By 1970, the region’s continuous mandate of progress had paved roads and erected buildings that told 150 years of industrial history in their ugly, collisive urban planning—ever new growth amidst the expanding junkyard of old progress. In the BBC documentary Synth Britannia, the narrator declares that “Victorian slums had been torn down and replaced by ultramodern concrete highrises,” but the images on the screen show more brick ruins than clean futurescapes, ceaselessly "ashing dystopian sky- lines of colorless smoke.1 Chris Watson of the She!eld band Cabaret Voltaire recalls in the late 1960s “being taken on school trips round the steelworks . just seeing it as a vision of hell, you know, never ever wanting to do that.”2 #is outdated hell smoldered in spite of the city’s supposed growth and improve- ment; a$er all, She!eld had signi%cantly enlarged its administrative territory in 1967, and a year later the M1 motorway opened easy passage to London 170 miles south, and wasn’t that progress? Institutional modernization neither erased northern England’s nineteenth- century combination of working-class pride and disenfranchisement nor of- fered many genuinely new possibilities within culture and labor, the Open Uni- versity notwithstanding. In literature and the arts, it was a long-acknowledged truism that any municipal attempt at utopia would result in totalitarianism. -

SIOBHÁN HAPASKA Born 1963, Belfast, Northern Ireland. Lives and Works in London, United Kingdom

SIOBHÁN HAPASKA Born 1963, Belfast, Northern Ireland. Lives and works in London, United Kingdom. Education 1985-88 Middlesex Polytechnic, London, United Kingdom. 1990-92 Goldsmiths College, London, United Kingdom. Solo Exhibitions 2021 Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin, Ireland. 2020 LOK, Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland. 2019 Olive, Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Paris, France. Snake and Apple, John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, United Kingdom. 2017 Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland. 2016 Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm, Sweden. 2014 Sensory Spaces, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. 2013 Hidde van Seggelen Gallery, London, United Kingdom. Siobhán Hapaska, Magasin 3 Stockholm Konsthall, Stockholm, Sweden. 2012 Siobhán Hapaska and Stephen McKenna, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland. Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm, Sweden. 2011 A great miracle needs to happen there, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland. 2010 The Nose that Lost its Dog, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, USA. The Curve Gallery, the Barbican Art Centre, London, United Kingdom. Ormeau Baths Gallery, Belfast, United Kingdom. 2009 The Nose that Lost its Dog, Glasgow Sculpture Studios Fall Program, Glasgow, United Kingdom. 2007 Camden Arts Centre, London, United Kingdom. Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, USA. 2004 Playa de Los Intranquilos, Pier Gallery, London, United Kingdom. 2003 cease firing on all fronts, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, Ireland. 2002 Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, USA. 2001 Irish Pavillion, 49th Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy. 1999 Sezon Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan. Artist Statement for Bonakdar Jancou Gallery, Basel Art Fair, Basel, Switzerland. Tokyo International Forum, Yuraku-Cho Saison Art Program Gallery, Aoyama, Tokyo, Japan. 1997 Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, USA. Ago, Entwistle Gallery, London, United Kingdom. Oriel, The Arts Council of Wales' Gallery, Cardiff, Wales, United Kingdom. -

Art, Crime, and the Image of the City

Art, Crime, and the Image of the City The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Kaliner, Matthew Erik. 2014. Art, Crime, and the Image of the City. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11744462 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Art, Crime and the Image of the City A dissertation presented by Matthew Kaliner to The Department of Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Sociology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts October, 2013 © 2014 Matthew Kaliner All rights reserved Dissertation Advisor: Robert J. Sampson Matthew Kaliner Art, Crime, and the Image of the City Abstract This dissertation explores the symbolic structure of the metropolis, probing how neutral spaces may be imbued with meaning to become places, and tracing the processes through which the image of the city can come to be – and carry real consequences. The centrality of the image of the city to a broad array of urban research is established by injecting the question of image into two different research areas: crime and real estate in Washington, DC and the spatial structure of grassroots visual art production in Boston, Massachusetts. By pursuing such widely diverging areas of research, I seek to show the essential linkage between art and crime as they related to the image of the city and general urban processes of definition, distinction, and change. -

Tomma Abts Francis Alÿs Mamma Andersson Karla Black Michaël

Tomma Abts 2015 Books Zwirner David Francis Alÿs Mamma Andersson Karla Black Michaël Borremans Carol Bove R. Crumb Raoul De Keyser Philip-Lorca diCorcia Stan Douglas Marlene Dumas Marcel Dzama Dan Flavin Suzan Frecon Isa Genzken Donald Judd On Kawara Toba Khedoori Jeff Koons Yayoi Kusama Kerry James Marshall Gordon Matta-Clark John McCracken Oscar Murillo Alice Neel Jockum Nordström Chris Ofili Palermo Raymond Pettibon Neo Rauch Ad Reinhardt Jason Rhoades Michael Riedel Bridget Riley Thomas Ruff Fred Sandback Jan Schoonhoven Richard Serra Yutaka Sone Al Taylor Diana Thater Wolfgang Tillmans Luc Tuymans James Welling Doug Wheeler Christopher Williams Jordan Wolfson Lisa Yuskavage David Zwirner Books Recent and Forthcoming Publications No Problem: Cologne/New York – Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings – Yayoi Kusama: I Who Have Arrived In Heaven Jeff Koons: Gazing Ball Ad Reinhardt Ad Reinhardt: How To Look: Art Comics Richard Serra: Early Work Richard Serra: Vertical and Horizontal Reversals Jason Rhoades: PeaRoeFoam John McCracken: Works from – Donald Judd Dan Flavin: Series and Progressions Fred Sandback: Decades On Kawara: Date Paintings in New York and Other Cities Alice Neel: Drawings and Watercolors – Who is sleeping on my pillow: Mamma Andersson and Jockum Nordström Kerry James Marshall: Look See Neo Rauch: At the Well Raymond Pettibon: Surfers – Raymond Pettibon: Here’s Your Irony Back, Political Works – Raymond Pettibon: To Wit Jordan Wolfson: California Jordan Wolfson: Ecce Homo / le Poseur Marlene -

Dorothy Cross Dorothy Cross B

Kerlin Gallery Dorothy Cross Dorothy Cross b. 1956, Cork, Ireland Like many of Dorothy Cross’ sculptures, Family (2005) and Right Ball and Left Ball (2007) sees the artist work with found objects, transforming them with characteristic wit and sophistication. Right Ball and Left Ball (2007) presents a pair of deflated footballs, no longer of use, their past buoyancy now anchored in bronze. Emerging from each is a cast of the artist’s hands, index finger extended upwards in a pointed gesture suggesting optimism or aspiration. In Family (2005) we see the artist’s undeniable craft and humour come together. Three spider crabs were found, dead for some time but still together. The intricacies of their form and the oddness of their sideways maneuvres forever cast in bronze. The ‘father’ adorned with an improbable appendage also pointing upwards and away. --- Working in sculpture, film and photography, Dorothy Cross examines the relationship between living beings and the natural world. Living in Connemara, a rural area on Ireland’s west coast, the artist sees the body and nature as sites of constant change, creation and destruction, new and old. This flux emerges as strange and unexpected encounters. Many of Cross’ works incorporate items found on the shore, including animals that die of natural causes. During the 1990s, the artist produced a series of works using cow udders, which drew on the animals' rich store of symbolic associations across cultures to investigate the construction of sexuality Dorothy Cross Right Ball and Left Ball 2007 cast bronze, unique 34 x 20 x 19 cm / 13.4 x 7.9 x 7.5 in 37 x 19 x 17 cm / 14.6 x 7.5 x 6.7 in DC20407A Dorothy Cross Family 2005 cast bronze edition of 2/4 dimensions variable element 1: 38 x 19 x 20 cm / 15 x 7.5 x 7.9 in element 2: 25 x 24 x 13 cm / 9.8 x 9.4 x 5.1 in element 3: 16 x 15 x 13 cm / 6.3 x 5.9 x 5.1 in DC17405-2/4 Dorothy Cross b. -

SPENCER FINCH Born 1962 in New Haven, CT Lives and Works in New

SPENCER FINCH Born 1962 in New Haven, CT Lives and works in New York www.spencerfinch.com Education Rhode Island School of Design, Providence in Sculpture 1989 Hamilton College, Clinton, NY B.A in Comparative Literature Doshisha University, Kyoto, Japan 1983-1984 Selected Solo Exhibitions 2021 Inventing Nature – Pflanzen in der Kunst, Kunsthalle Karlsruhe The Enigma of Color, Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin Only the hand that erases writes the true thing, Lisson Gallery, London 2020 Woodcutter. Cut from me my shadow, Lisson Gallery, East Hampton, NY looking around, gazing intently, beholding, Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago, IL 2019 As Lightning on a Landscape, Arcadia University,Spruance Gallery, Glenside, PA Wind (Through Emily Dickinson’s Window), College of Visual & Performing Arts,University of Massachusetts,North Dartmouth, MA No Ordinary Blue, Lisson Gallery, London 2018 The brain is deeper than the sea, James Cohan Gallery, New York, NY Fifteen stones (Ryōan-ji), Fundació Mies van der Rohe, Barcelona, Spain Me, Myself and I (A Group Show), Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco, CA Moon Dust (Apollo 17) Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD 2017 Spencer Finch: Great Salt Lake and Vicinity, Utah Museum of Fine Art, The University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT Spencer Finch, Lisson Gallery, Milan Spotlight, Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, FL The Western Mystery, Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA Cosmic Latte, Mass MOCA, North Adams, MA The eye you see is not an eye because you see it, it is an eye because it sees you, Galerie Nordenhake, -

Human League Dare Mp3, Flac, Wma

Human League Dare mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Dare Country: Taiwan Released: 1981 Style: Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1454 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1299 mb WMA version RAR size: 1116 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 573 Other Formats: AAC MOD XM MP2 TTA AU VOX Tracklist Hide Credits The Things That Dreams Are Made Of A1 4:14 Written-By – Wright*, Oakey* Open Your Heart A2 3:53 Written-By – Callis*, Oakey* The Sound Of The Crowd A3 3:56 Written-By – Buirden*, Oakey* Darkness A4 3:56 Written-By – Callis*, Wright* Do Or Die A5 5:23 Written-By – Burden*, Oakey* Get Carter B1 1:02 Written-By – Budd* I Am The Law B2 4:14 Written-By – Wright*, Oakey* Seconds B3 4:58 Written-By – Callis*, Wright*, Oakey* Love Action (I Believe In Love) B4 4:58 Written-By – Burden*, Oakey* Don't You Want Me B5 3:56 Written-By – Callis*, Wright*, Oakey* Companies, etc. Distributed By – Rock Records – RCHC186 Credits Engineer [Assistant] – Dave Allen* Producer – Martin Rushent, The Human League Synthesizer – Ian Burden, Jo Callis Synthesizer [Occasional], Other [Slides] – Philip Adrian Wright Vocals – Joanne Catherall, Susanne Sulley Vocals, Synthesizer – Philip Oakey Notes Official Virgin release distributed by Rock Records. Cassette inlay extends out of case and folds around the plastic case. Includes a fold out lyrics insert & a small Record label insert. Comes in company logo and text embossed clear cassette case. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Human Dare (LP, Album, V2192 Virgin V2192 -

WILLIAM MCKEOWN Born in Co Tyrone, Northern Ireland, 15 April 1962 – Died in Edinburgh, Scotland, 25 October 2011

WILLIAM MCKEOWN born in Co Tyrone, Northern Ireland, 15 April 1962 – died in Edinburgh, Scotland, 25 October 2011 EDUCATION 1993-94 M.A. Fine Art, University of Ulster, Belfast 1986-87 M.A. Design, Glasgow School of Art 1981-84 Textile Design, Central/St Martin's School of Art & Design, London 1980-81 University College, London SOLO & TWO-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2013 William McKeown, St Carthage Hall, Lismore Castle Arts, Ireland. Curated by Eamonn Maxwell 2012 William McKeown, Inverleith House, Edinburgh. Curated by Paul Nesbitt A Room, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin 2011 The Waiting Room, The Golden Bough, Dublin City Gallery, The Hugh Lane, Dublin. Curated by Michael Dempsey 2010 Five Working Days, Ormeau Baths Gallery, Belfast A Certain Distance, Endless Light, with works by Félix González-Torres, mima, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. Curated by Gavin Delahunty Pool, with Dorothy Cross, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin 2008/09 William McKeown, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin 2006 Hope Paintings, Hope Drawings and Open Drawings, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin 2004 The Bright World, The Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast The Room At The Horizon, Project Arts Centre, Dublin. Curated by Grant Watson Cloud Cuckoo-Land, The Paradise (16), Gallery 2, Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin. Curated by John Hutchinson Cloud Cuckoo-Land, Sleeper, Edinburgh 2002 The Sky Begins At Our Feet, Ormeau Baths Gallery, Belfast Forever Paintings, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin 2001 In An Open Room, Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin. Curated by John Hutchinson 1998 Kerlin Gallery, Dublin 1996 Kerlin Gallery, Dublin GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2015 The Untold Want, Royal Hibernian Academy, Dublin. Curated by Caroline Hancock and Patrick T. -

The Daily Egyptian, February 24, 1982

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC February 1982 Daily Egyptian 1982 2-24-1982 The aiD ly Egyptian, February 24, 1982 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_February1982 Volume 67, Issue 105 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, February 24, 1982." (Feb 1982). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1982 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in February 1982 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Daily 'Egyptian Wednesday, February 24, 1982-Vol. 67, No. 105 Southern Illinois University Plan says city must fund.,,- social. services By Belt BaadIlJ'llllt ~..lrograms are lunded IocaI social service programs at S&aff Wrker D~70~ the federal Community the same level, it would take a More funding sources for Deve opme1tnt woulBIOCd IE.... Grant property tax levy as great as $1 program. n: tran- Del' $100 assessed valuation, but Carbondale social service sferred to the states under f'f don't ."'_L. the programs Deed to be found at President Ronald Reagan's will stand;:." that =~ the local level, city ad- New Federalism propoll8.l. costs," be said. mini&trators told the City But the city is unsure whether Stalls told the c:ouncll that the Council MOIlday. the state would issue block repoI1 was still being reviewed A fiAal draft of the Car- grant funds and is expecting m by several consultants aod bondaJe HUIDIlD Services Plan further block ~nts from the ask..."Jd for any criticism of the =::m!~ ~::= f:; ~.:- 5.~te~flYernmeota ~'dG not Human Resources Director This ....